Life Purpose Development Among University Faculty

advertisement

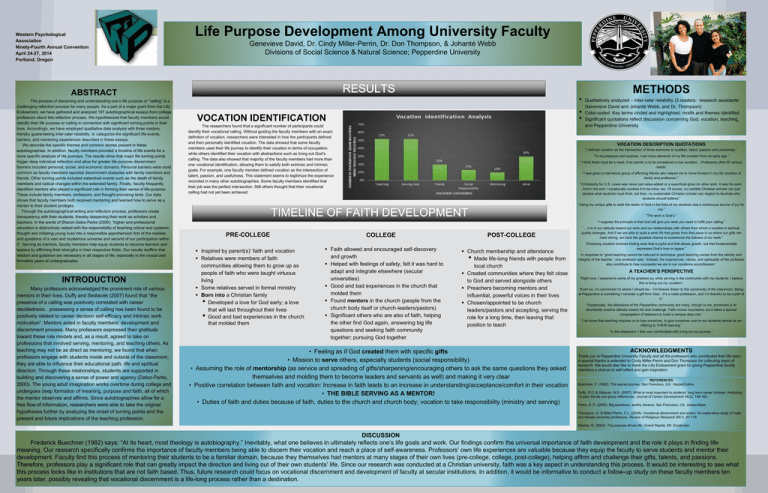

Western Psychological Association Ninety-Fourth Annual Convention April 24-27, 2014 Portland, Oregon Life Purpose Development Among University Faculty Genevieve David, Dr. Cindy Miller-Perrin, Dr. Don Thompson, & Johanté Webb Divisions of Social Science & Natural Science; Pepperdine University ABSTRACT The process of discerning and understanding one’s life purpose or “calling” is a challenging reflection process for many people. As a part of a major grant from the Lilly Endowment, we have gathered and analyzed 197 autobiographical essays from college professors about this reflection process. We hypothesized that faculty members would identify their life purpose or calling in connection with significant turning points in their lives. Accordingly, we have employed qualitative data analysis with three readers, thereby guaranteeing inter-rater reliability, to categorize the significant life events, barriers, and mentoring experiences described in these essays. We describe the specific themes and common stories present in these autobiographies. In addition, faculty members provided a timeline of life events for a more specific analysis of life journeys. The results show that major life turning points trigger deep individual reflection and allow for greater life-purpose discernment. Barriers included personal, social, and economic domains. Personal barriers were most common as faculty members reported discernment obstacles with family members and friends. Other turning points included watershed events such as the death of family members and radical changes within the extended family. Finally, faculty frequently identified mentors who played a significant role in forming their sense of life-purpose. These include family members, professors, and thought-provoking texts. Our data shows that faculty members both received mentoring and learned how to serve as a mentor to their student protégés. Through the autobiographical writing and reflection process, professors create transparency with their students, thereby deepening their work as scholars and teachers. In the words of Sharon Daloz-Parks (2000): “higher and professional education is distinctively vested with the responsibility of teaching critical and systemic thought and initiating young lives into a responsible apprehension first of the realities and questions of a vast and mysterious universe and second of our participation within it”. Serving as mentors, faculty members help equip students to become learners and leaders by affirming their strengths in their respective fields. Our results reaffirm that wisdom and guidance are necessary in all stages of life, especially in the crucial and formative years of undergraduates. INTRODUCTION Many professors acknowledged the prominent role of various mentors in their lives. Duffy and Sedlacek (2007) found that “the presence of a calling was positively correlated with career decidedness…possessing a sense of calling has been found to be positively related to career decision self-efficacy and intrinsic work motivation”. Mentors aided in faculty members’ development and discernment process. Many professors expressed their gratitude toward these role models and, as a result, agreed to take on professions that involved serving, mentoring, and teaching others. As teaching may not be as direct as mentoring, we found that when professors engage with students inside and outside of the classroom, they are able to influence their educational path, life and spiritual direction. Through these relationships, students are supported in building and discovering a sense of power and agency (Daloz-Parks, 2000). The young adult imagination works overtime during college and undergoes deep formation of meaning, purpose and faith, all of which the mentor observes and affirms. Since autobiographies allow for a free flow of information, researchers were able to take the original hypotheses further by analyzing the onset of turning points and the present and future implications of the teaching profession. • • • VOCATION IDENTIFICATION The researchers found that a significant number of participants could identify their vocational calling. Without guiding the faculty members with an exact definition of vocation, researchers were interested in how the participants defined and then personally identified vocation. The data showed that some faculty members used their life journey to identify their vocation in terms of occupation, while others identified their vocation with abstractions such as living out God’s calling. The data also showed that majority of the faculty members had more than one vocational identification, allowing them to satisfy both extrinsic and intrinsic goals. For example, one faculty member defined vocation as the intersection of talent, passion, and usefulness. This statement seems to legitimize the experience recorded in many other autobiographies. Some faculty members identified that their job was the perfect intersection. Still others thought that their vocational calling had not yet been achieved. METHODS Qualitatively analyzed – inter-rater reliability (3 readers: research assistants Genevieve David and Johanté Webb, and Dr. Thompson) Color-coded: Key terms circled and highlighted; motifs and themes identified Significant quotations reflect discussion concerning God, vocation, teaching, and Pepperdine University VOCATION DESCRIPTION QUOTATIONS “I defined vocation as the intersection of three elements or qualities: talent, passion and usefulness.” “To my pleasure and surprise, I can trace elements of my life vocation from an early age.” “I think there must be a need, if an activity is to be considered a true vocation... Professors often fill various needs” “I was given a marvelous group of affirming friends who helped me to move forward in my life vocation of family and profession.” “Christianity for C.S. Lewis was never just value-added or a superficial gloss on other work. It was his work. And in the end, I vocationally confess it to be mine, too. Of course, no credible Christian scholar can just declare what students must think, but then, no sustainable Christian scholar can neglect to illustrate why students should believe.” “Using my unique gifts to work the works of God in the lives of my students was a continuous source of joy for me.” “The work is God’s.” “I suppose the principle is that God will give you what you need to fulfill your calling.” PRE-COLLEGE Inspired by parent(s)’ faith and vocation Relatives were members of faith communities allowing them to grow up as people of faith who were taught virtuous living Some relatives served in formal ministry Born into a Christian family Developed a love for God early; a love that will last throughout their lives Good and bad experiences in the church that molded them • • COLLEGE Faith allowed and encouraged self-discovery and growth Helped with feelings of safety, felt it was hard to adapt and integrate elsewhere (secular universities) Good and bad experiences in the church that molded them Found mentors in the church (people from the church body itself or church-leaders/pastors) Significant others who are also of faith, helping the other find God again, answering big life questions and seeking faith community together; pursuing God together POST-COLLEGE Church membership and attendance Made life-long friends with people from local church Created communities where they felt close to God and served alongside others Preachers becoming mentors and influential, powerful voices in their lives Chosen/appointed to be church leaders/pastors and accepting, serving the role for a long time, then leaving that position to teach • • Feeling as if God created them with specific gifts • Mission to serve others, especially students (social responsibility) • Assuming the role of mentorship (as service and spreading of gifts/sharpening/encouraging others to ask the same questions they asked themselves and molding them to become leaders and servants as well) and making it very clear • Positive correlation between faith and vocation: Increase in faith leads to an increase in understanding/acceptance/comfort in their vocation • THE BIBLE SERVING AS A MENTOR! • Duties of faith and duties because of faith, duties to the church and church body; vocation to take responsibility (ministry and serving) “…it is in our attitude toward our work and our relationships with others from which a vocation’s spiritual quality emerges. And if we are able to build a work life that grows from that place in us where our gifts are most strong, we have the greatest chance to experience the fullness of our work.” “Choosing vocation involves finding work that is joyful and that allows growth, but that fundamentally expresses God’s love or agape.” In response to “good teaching cannot be reduced to technique; good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher,” one professor said, “Instead, the experiences, values, and spirituality of the professor also contribute to how successful we are in our vocations as professors.” A TEACHER’S PERSPECTIVE “Right now, I experience some of my greatest joy while serving in the community with my students. I believe this is living out my vocation.” “Even so, I’m convinced I’m where I should be – I’m forever drawn to the community of the classroom. Being at Pepperdine is something I consider a gift from God…It’s a noble profession, and I’m thankful to be a part of it.” “Vocationally, the attractions of the Pepperdine community are many, though to me, prominent is its abundantly positive attitude toward life and challenge. Faith moves mountains, but it takes a special congregation of believers to build a campus atop one.” “I do know that teaching requires us to lose ourselves, to give ourselves over to our students almost as an offering to THEIR learning.” “In the classroom, I feel very comfortable with living out my journey.” ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to Pepperdine University Faculty and all the professors who contributed their life story. A special thanks is extended to Cindy Miller-Perrin and Don Thompson for collecting years of research. We would also like to thank the Lilly Endowment grant for giving Pepperdine faculty members a chance to self-reflect and gain inspiration. REFERENCES Buechner, F. (1982). The sacred journey. San Francisco, CA: HarperCollins. Duffy, R.D. & Sdlacek, W.E. (2007). What is most important to students’ long term career choices: Analyzing 10-year trends and group differences. Journal of Career Development 34(2), 149-163. Parks, S. D. (2000). Big questions, worthy dreams. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Thompson, D. & Miller-Perrin, C.L. (2008). Vocational discernment and action: An exploratory study of male and female university professors. Review of Religious Research 50(1), 97-119. Warren, R. (2002). The purpose driven life. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. DISCUSSION Frederick Buechner (1982) says: “At its heart, most theology is autobiography.” Inevitably, what one believes in ultimately reflects one’s life goals and work. Our findings confirm the universal importance of faith development and the role it plays in finding life meaning. Our research specifically confirms the importance of faculty members being able to discern their vocation and reach a place of self-awareness. Professors’ own life experiences are valuable because they equip the faculty to serve students and mentor their development. Faculty find this process of mentoring their students to be a familiar domain, because they themselves had mentors at many stages of their own lives (pre-college, college, post-college), helping affirm and challenge their gifts, talents, and passions. Therefore, professors play a significant role that can greatly impact the direction and living out of their own students’ life. Since our research was conducted at a Christian university, faith was a key aspect in understanding this process. It would be interesting to see what this process looks like in institutions that are not faith based. Thus, future research could focus on vocational discernment and development of faculty at secular institutions. In addition, it would be informative to conduct a follow-up study on these faculty members ten years later, possibly revealing that vocational discernment is a life-long process rather than a destination.