The Birth of Democracy

advertisement

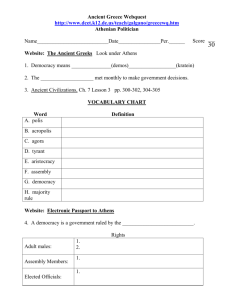

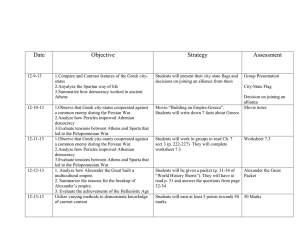

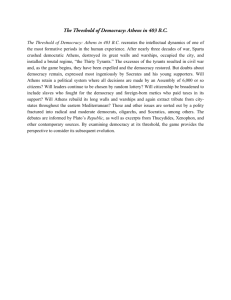

Archaeology and Text: The Birth of Democracy: An Exhibition Celebrating the 2500th Anniversary of Democracy The exhibition The Birth of Democracy: An Exhibition Celebrating the 2500th Anniversary of Democracy was held at the National Archives in Washington DC from 15 June 1993 to 2 January 1994. The show had previously been on display from 9 March to 9 May 1993 at the Gennadius Library in Athens. Like The Greek Miracle exhibition, it marked the 2,500th anniversary of Kleisthenes’ reforms of the Athenian constitution in 507/8 BCE, which, it is argued, marked a change in political practice and led to democracy in Athens. The Birth of Democracy displayed archaeological artefacts from the time of Solon’s reforms through to Kleisthenes’ reforms and then through to the late fourth century BCE to illustrate the practice and development of Athenian democracy. The exhibition was organised by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens’ ‘Democracy 2,500’ project in co-operation with the National Archives and Records Administration of the United States, as well as with the support of the Ministry of Culture in Greece. Many of the objects came from American led excavations in the Agora in Athens and had not been on display in the US before, but were usually exhibited in the Agora Museum in Athens. The exhibition, though prominent and exhibiting many objects previously unseen in the US, did not attract the same kind of media attention as The Greek Miracle. However, in many ways it was more relevant to the actual practice of participatory democracy in Athens and utilised a similar theme of America and Greece sharing a democratic heritage. The Lenders and the Objects The objects on display in The Birth of Democracy: An Exhibition Celebrating the 2500th Anniversary of Democracy comprised small items such as ostraca shards to Greek vases and busts, as well as models of buildings in ancient Athens and photographs of past and present excavations. The items were lent by a number of museums in Greece, America and elsewhere in Europe. The complete list is: the National Archaeological Museum, Athens; Acropolis Museum, Athens; Agora Museum, Athens; Antiken Sammlung Kunst Historisches Museum, Vienna; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; John Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Department of the History of Art, Cornell University; Museum of Art and Archaeology at University of Missouri, Columbia; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; University Museum, University of Pennsylvania; and the Art Museum, Princeton University. The range of museums – small university museums as well as large institutions – gives a sense of the wide-ranging nature of the exhibition and the wealth of objects on display. The majority of the objects were small in size and grouped together in display cabinets by theme. The catalogue to the exhibition has been put on-line. 1 The themes of the exhibition chronologically illustrated the development of Athenian democracy and its aftermath. The themes were Athens Before Democracy, The Kleisthenic Reforms: 1 The Birth of Democracy: An Exhibition Celebrating the 2500th Anniversary of Democracy, on the Excavations in the Agora website, http://www.attalos.com/cgi-bin/text?lookup=democracy;id=Contents (accessed 11/06/2008) 1 Creation of the Democracy, Athenian Democracy: Legislature, Athenian Democracy: Judiciary, The Protection of Democracy and Criticism of Democracy. Objects were displayed in sub-headings or groupings under these themes. In order to give a sense of the type of objects exhibited and the range of the material, twelve objects will be highlighted here. The first catalogue number 00.01 is a plaster cast after a bust of Pericles (ca. 500 - 429 B.C.) that is in the British Museum (the cast comes from Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri, Columbia). Pericles is highlighted as one of the ‘great statesman of classical Athens’ who was responsible for building the Parthenon and other monuments on the Acropolis (illustration 1). Pericles is presented as one of the heroes of democracy. The cast of Pericles illustrates that this exhibition had no qualms about using replicas and also used reconstructions of public buildings in Athens. An example of a reconstructed model on display is catalogue number 00.03B The Athenian Agora c. 400 by Fetros Demetriades and Kostas Papoulias (Agora Museum, Athens). This model shows one of the most important public buildings in the function of democracy in Athens (illustration 2). Unlike The Greek Miracle exhibition, there was no actual sculpture on display but a photograph of a Greek Kouros was used instead, such as Catalogue number 1.5 (illustration 3). This photograph of a statue of a youth (kouros) ‘Kroisos’ is from the collection of the National Archaeological Museum (no. 3851). Rather than illustrating the development of a naturalistic style of art from the sixth to the fifth centuries, this photograph of a sculpture is used to illustrate the aristocratic commemoration of the dead. This statue had an inscription at the base reading: ‘Stay and mourn at the monument of dead Kroisos whom furious Ares destroyed one day as he fought in the front ranks.’ The fragment of an inscription from a statue base possibly from the statues of Harmodios and Aristogeiton in c.475 BCE is catalogue number 4.1 (Agora Museum, Athens 13872). This fragment is important, as these figures were known as the ‘tyrannicides’ who were revered in ancient Athens (and in modern times) for assassinating the tyrant Hipparchos (illustration 4). A bronze sculpture of the pair was commissioned by the Athenians and then taken by the Persians in 480 BCE. Although a replacement was made and the original returned to Athens after Alexander the Great sacked Persepolis in the fourth century (both stood together in the Agora), the originals have been lost and so a photograph of a Roman copy in Naples is displayed with the inscription. A profile of the ‘tyrannicides’ from a fragment of a red figure oinochoe (jug) c. 400 BCE is also displayed to illustrate the pair’s mythic importance as well as that of the sculpture. Each of the major democratic institutions of ancient Athens were represented by a group of objects. Lead tokens used as payment for attending the Assembly of ancient Athens – one of the main forums in which Athenian male citizens participated in democracy – were on display from 4th century BCE (Agora Museum, Athens IL 656, 819, 893, 944, 1146, 1173, 1233). ‘These small tokens were turned in for pay, allowing poor citizens to participate without losing a day’s wages’, and so were crucial to participatory democracy (illustration 5). The Boule, or Council of 500, and a product of the reforms of Kleisthenes 2 was represented by among other objects, catalogue number 8.1 a fragment of a marble basin c. 500 BCE (Agora Museum, Athens 14869) that preserves part of an inscription around the rim which reads ‘of the Bouleuterion’ (illustration 6). The Judiciary of Athens was represented by (among other items) catalogue number 12.1 a fragmentary waterclock (or klepsydra) with various inscriptions from late 5th century BCE that was used to time the speakers at trials (Agora Museum, Athens P 2084) (illustration 7). Pericles may have been a hero of Athenian democracy but he was also a frequent candidate for ostracism as catalogue number 14.6 Ostrakon of Perikles from the mid-5th century BCE illustrates (Agora Museum, Athens P 16755). Although Perikles was never ostracised, this example illustrates how the Athenian citizens protected their rights against men considered to grow too powerful and become potential threats to democracy (illustration 8). Photographs of excavations and reconstructions made up the material of the exhibition as catalogue number 17.4 a photograph of a trireme under sail illustrates (Paul Lipke, The Trireme Trust). The reconstructed trireme was built under the supervision of John Morrison, a classical scholar, and John Coates, a naval architect and was used to illustrate evidence for the Athenian navy in the exhibition (illustration 9). Female Athenian citizens, could not vote and did not directly participate in Athenian democracy had representation in this exhibition. Catalogue no. 22.3 a terracotta statuette of a woman kneading bread, early 5th century BCE (National Archaeological Museum, Athens 6006) shows a woman in a daily domestic occupation, but one which was crucial to the households of Athenian citizens (illustration 10). Slaves and slavery were also represented in the exhibition through the depiction of them on vases. This Athenian (Attic) vase in the form of the head of an African from late 6th century BCE (National Archaeological Museum, Athens 11725) shows a non-Athenian and is here used to represent a slave, though it could simply have represented the features of a different race (illustration 11). Continuity between Athens and America was provided by documents from eighteenth century and contemporary America at the end of the exhibition, though the difference between the participatory democracy of Athens and representative democratic system of America is stressed. Catalogue number 26.1 (illustration 12) is a copy of Rights of Man by Thomas Paine from the collection of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC: ‘Written in 1792 in defence of the French Revolution, Thomas Paine's Rights of Man is a statement of republican ideals. Paine believed that America had adapted the virtues of ancient Greek democracy to the modern world.’ The range of material on display in the exhibition is apparent from just this short list of some of the objects. Vases, inscriptions, practical items as well as photographs and reconstructions were all used to present the evidence for the story of Athenian democracy. Photographs of items traditionally considered as ‘art objects’ were used in the exhibition but in the context of their connection with the social history of democracy rather than to tell an overarching theory of the development of art in this period. All the items, with a few exceptions, were from Athens or Attica and often from the site of the Agora (or marketplace) in Athens itself. The objects were often put in context with textual evidence 3 from ancient Athens and texts such as The Constitution of Athens or Pericles’ ‘Funeral Oration’ from Thucydides’ Histories were used to highlight the use of these objects. The practical and literary significance of the objects on display in The Birth of Democracy was possibly due to the fact that it was essentially an exhibition of archaeological artefacts within a national library. History Heroes and Texts The Birth of Democracy opened with the casts of busts of two prominent exponents of democracy from the fifth and fourth centuries: Pericles and Demosthenes. References to the speeches they made in praise of democracy were included in the catalogue. The speeches of Demosthenes and the ‘Funeral Oration’ of Pericles as recorded by Thucydides in his Histories were clearly key texts. Pericles and Demosthenes were highlighted as the main players in the development of Athenian democracy. However, they were not alone. A section on the reforms of Solon in the early sixth century BCE illustrated the political tensions in Athens one hundred years before the changes made by Kleithenes. Inevitably Kleisthenes’ creation of ten new tribes and his political reorganisation of the Athenian constitution merited its own section. Other notable people considered in the exhibition included the successful general Themistocles, who was ostracised from Athens, and the philosopher Socrates, who was ultimately condemned to death by an Athenian jury. The catalogue for The Birth of Democracy drew on a great range of texts but mainly quoted from Plutarch’s Lives (Solon, Kleisthenes, Pericles and Demosthenes in particular), Thucydides’ Histories, The Old Oligarch’s/Aristotle’s The Athenian Constitution and Politics, Xenophon’s The Constitution of the Athenians, as well as conversations of Socrates recorded by Plato and Xenophon (especially the texts in relation to Socrates’ trial). A section on theatre referred to Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Menander and quoted from the comedies of Aristophanes. A short section on ‘Sources and Documents’ stressed the importance of the treatises on the Athenian constitution by Aristotle and ‘pseudo-Xenophon’ but also points out the usefulness of evidence from inscriptions and other fragmentary documents or writings that have often been found in the Agora. The Birth of Democracy drew on texts and inscriptions as evidence in the development and history of democracy and emphasised key individuals in the story of democratic practice. Curation of The Birth of Democracy The exhibition was curated by Diana Buitron-Oliver and John Mck Camp II as part of the project ‘Democracy 2,500’ which was directed by Josiah Ober and Charles W. Hedrick. The exhibition was designed by Michael Graces and objects were moved by Art Services International. The Public Programs and Education team at the National Archives arranged the public programme of events and learning activities. Diana Buitron-Oliver co-curated The Birth of Democracy. Buitron-Oliver was a classical archaeologist and lecturer at Georgetown University in Washington DC and had 4 previously curated The Human Figure in Early Greek Art at the National Gallery of Art in 1988 (January 31 – June 12 1988). Buitron-Oliver was also guest curator of The Greek Miracle. Classical Sculpture from the Dawn of Democracy at the National Gallery of Art Washington DC and Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, which closed at New York in May 1993 shortly before The Birth of Democracy opened. Buitron-Oliver’s co-curator was Professor John Mck Camp II, Director of Excavations at the Athenian Agora, American School of Classical Studies at Athens. The exhibition was part of the ‘Democracy 2,500’ project, which was directed by Josiah Ober and Charles W. Hedrick. Josiah Ober was at that point Professor of Classics at Princeton University as well as author of a number of publications on Athenian democracy, the most notable at the time being the book Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People (Princeton, 1989). Charles W. Hedrick was professor of history at UC Santa Cruz. Interpretation and Location The Birth of Democracy had very few reviews – in fact only one short review of the actual exhibition has so far been found in Minerva – and so it is hard to reconstruct the layout and interpretation of the exhibition. It was exhibited in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom in the National Archives, an impressive neoclassical building behind the Mall (the main public space on which many museums and national collections are positioned), which opened in 1952 in Washington DC (illustration 13). In the ‘Introduction to the Exhibition’, the curators of the exhibition Diana Buitron-Oliver and John Mck. Camp II compare the buildings in which democracy took place in the Agora in Athens with public space in Washington DC: Administrative, political, judicial, commercial, social, cultural, and religious activities all found a place here together in the heart of ancient Athens. In modern terms it would be the village green of a traditional American town, or, on a large scale, the Mall in Washington, D.C.2 The National Archives contains an impressive collection of documents as well as archival material relating to American governance over the last 200 years and more. It displays the Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution and the Bill of Rights in the main Rotunda. The Birth of Democracy began in the Rotunda with free standing statues of Pericles and Demosthenes and an introduction to the exhibition. The Rotunda itself has murals on the side walls illustrating significant scenes in the story of America’s democracy, such as Thomas Jefferson handing the declaration to John Hancock (illustration 14). In this way the birth of Athenian democracy was displayed against the backdrop of the birth of American democracy, as Jerry Theodorou in his review for Minerva noted: Diana Buitron-Oliver and John Mck. Camp II, ‘Introduction to the Exhibition’ in Josiah Ober and Charles W. Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy. An Exhibition Celebrating the 2,500 th Anniversary of Democracy (American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Washington DC, 1993), pp. 29-35, p. 30. 2 5 The cases [of the exhibition] are situated near the chief attractions that draw visitors to the National Archives in the Washington Mall – the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The proximity of the ancient Athenian artefacts relating to democracy to the seminal early American documents is appropriate because the system was among the sources of inspiration for the American system of government.3 Though Theodorou also notes that Athenian democracy acted as a ‘warning’ to the founders of the American constitution and was viewed with suspicion and ultimately the system of Republican Rome found more favour with the founding fathers. The exhibition had 26 display cases and each focused on an institution of Athenian democracy or around an area of life in Athens, displaying objects and photographs connected with that area or institution. The exhibition started before the emergence of democracy with a consideration of oligarchic Athens and the early reforms set in motion by Solon. It finished with key documents from the writers and founders of the American constitution. The catalogue followed the same order as the exhibition so the themes of the display cases can easily be seen: Introduction to the Exhibition; Free Standing Objects in Rotunda; Models of the Athenian Agora; Marble Stele Recording a Law Against Tyranny Athens Before Democracy 1. The Athenian Aristocracy 2. Solon the Lawgiver 3. Tyranny 4. Overthrow and Revolution The Kleisthenic Reforms: Creation of the Democracy 5. The Ten New Tribes 6. Political Organization of Attica: Demes and Tribal Representation Athenian Democracy: Legislature 7. The Ekklesia (Citizens' Assembly) 8. The Boule (Senate) 9. The Prytaneis (Executive Committee of the Senate) Athenian Democracy: Judiciary 10. Popular Courts 11. The Jury 12. The Speakers 13. The Verdict The Protection of Democracy Jerry Theodorou, ‘The Birth of Democracy. 2,500 th Anniversary celebrated in an exhibition in Washington DC’, Minerva, July/August 1993 (Vol. 4, No. 4), 16-17, 16. 3 6 14. Ostracism 15. Factional Politics: The Ostracism of Themistokles 16. The Athenian Army 17. The Athenian Navy 18. Administration and Bureaucracy 19. State Religion: The Archon Basileus Criticism of Democracy 20. Sokrates 21. Theater 22. The Unenfranchised, I - Women 23. The Unenfranchised, II - Slaves and Resident Aliens 24. Sources and Documents 25. The Founding Fathers and Athenian Democracy 26. Democracy from the Past to the Future4 Much of the material on display came from excavations of the Agora carried out by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and is ‘intended to illustrate and tell the story of the development of democracy in Athens.’5 The exhibition’s emphasis on the buildings and spaces of ancient Athens in which democracy functioned also stressed the: [. . .] the extraordinary similarities between our own times and then. The Athenian government, too, was divided into three branches, executive, judiciary, and legislative, with authority divided among them.6 The curators stressed that ‘an effort has also been made to allow the ancient Athenians to speak for themselves’ through the use of texts, inscriptions and scenes on vases of daily life in and the workings of democracy in Athens. The combination of this sort of material and the focus on the function and practice of democracy in Athens made The Birth of Democracy a very different exhibition to The Greek Miracle. The archaeological artefacts are displayed in what Shanks and Tilley have termed a ‘humanizing narrative’ – setting the objects on display within a ‘concrete’ human context through the use of text, reconstructions, maps etc. 7 This and the exploration of the function of democracy in Athens as well as a brief consideration of those not included in the democratic process made The Birth of Democracy a more nuanced social exploration of Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries than The Greek Miracle. The Catalogue 4 Josiah Ober and Charles W. Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy. An Exhibition Celebrating the 2,500th Anniversary of Democracy (American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Washington DC, 1993), p. 28. 5 Buitron-Oliver and Mck. Camp II, ‘Introduction to the Exhibition’ (1993), p. 30. 6 Buitron-Oliver and Mck. Camp II, ‘Introduction to the Exhibition’ (1993), p. 30. 7 Michael Shanks and Christopher Tilley, Re-constructing Archaeology: Theory and Practice (London: Routledge, 1992), p. 73. 7 The main catalogue text for The Birth of Democracy was written by the curators Diana Buitron-Oliver and John Mck. Camp II but a number of essays on specific areas of Athenian democracy and life were contributed by other scholars. These scholars were mainly from American universities and/or the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, though two directors of museums in Greece also contributed essays. The essays explored different areas of Athenian democracy and life in more detail than the exhibition and, though the catalogue acknowledged that Athenian democracy contained much that the ‘modern democrat would find repugnant’, as a whole it was celebratory about the democratic achievements of Athens.8 In his ‘Introductory Remarks’, Josiah Ober commented on the importance of the timing of the 2,500th anniversary of ancient democracy with contemporary events. Noting that democracy had not always been regarded as a positive political system, Ober considers that the timing of the anniversary is opportune: Today, democracy has come to be virtually synonymous with fair, free government; the last quarter of the twentieth century could quite easily be designated ‘The Age of Democracy’ by future historians. Thus it is a very happy coincidence that the decade of the 1990s (specifically 1993) will mark democracy’s 2,500th anniversary.9 Ober outlines the reforms of Kleisthenes, which is what the anniversary is celebrating. He considers that the achievements of Athenian democracy have been obscured by most historians and texts from the period (and since) as they have been critical of the political system in Athens for their own ideological purposes. On the other hand, archaeology, Ober argues, has recaptured not just the systems and practical elements of democracy but also some of the excitement about the political process. Ober considers an understanding of Athenian democracy important, if not crucial, to understanding debates within modern democracy. He presents the other essayists as looking at many diverse modern views to ‘help readers to refine their own understanding of the historical status and the future of democracy as a way of government and as a way of life.’10 William D. E. Coulson (Director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens) carries on the consideration of the relationship between ancient Athenian and modern American democracy in the second part of the ‘Introductory Remarks’. Arguing that the reforms of Kleisthenes are the ‘basis of democratic ideals today’, Coulson argues that it is particularly appropriate that the exhibition takes place in the National Archives in Washington DC ‘where the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America are displayed.’11 Stressing that The Birth of Democracy is a Josiah Ober, ‘Introductory Remarks I. The Athenian Revolution’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), p. 1-3, p. 2. 9 Josiah Ober, ‘Introductory Remarks I. The Athenian Revolution’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), p. 1-3, p. 3. 10 Josiah Ober, ‘Introductory Remarks I. The Athenian Revolution’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), p. 1-3, p. 3. 11 William D. E. Coulson, ‘Introductory Remarks II. Athens and America’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), p. 4-5, p. 4 8 8 public exhibition for a non-specialist audience, Coulson contends that the excavations of the American School of Classical Studies in Athens in the Athenian Agora are crucial for the greater consideration and knowledge about Athenian democracy since 1931. He sees these excavations and their finds as a further connection in the shared democratic heritage of Athens and contemporary America. There were of course political considerations behind these American funded excavations in the Athenian Agora, as Stephen Dyson points out, since after WW2 they took place against the backdrop of the Greek Civil War in which the US backed the installed government and then under the dictatorship of the Generals, whose regime had also been backed by the US in the 1960s.12 Democracy was not been achieved by modern Greece easily in the twentieth century and, arguably, accountable governments have not always been assisted by the American government. Katerina Romiopoulou’s essay on ‘Democracy and Freedom’, which closes the ‘Introductory Remarks’ considers in hyperbolic language, that democracy cannot exist without human freedom.13 Other essays in the catalogue consider the practicalities behind the function of Athenian democracy. Charles W. Hedrick, for example, considers the function of writing in democratic Athens in terms of recording statutes and verdicts, but argues that essentially democracy was based on the ‘spoken word’.14 The abstract personification of ‘demos’ or ‘the people’ and democracy is considered on document reliefs and monuments by Carol Lawton and Olga Tzachou-Alexandri respectively. 15 Peter G. Calligas considered the background to Kleisthenes’ reforms and the struggles involved in the foundation of Athenian democracy. 16 The private lives of Athenians then considered through the paintings on pottery by Alan Shapiro, while more detailed examination of the judiciary is made by Alan L. Boegehold and of oaths of allegiance by Dina Peppa-Delmouzou.17 Two essays on the reception of democracy are also included. Jennifer Roberts, later author of the polemic Athens on Trial in 1994, considers the reluctance of the American founders to base their constitution on ancient Athens since they considered it led to military weakness and involved the redistribution of wealth. This latter point is important as Roberts stresses that the ‘founding fathers’ of America sprang from the propertied classes and many of them, such as John Adams, thought classical Athens violated the sanctity of 12 Stephen L. Dyson, In Pursuit of Ancient Pasts. A History of Classical Archaeology in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Yale: Yale University Press, 2006), p. 219. 13 Katerina Romiopoulou, ‘Introductory Remarks II. Democracy and Freedom’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), p. 6. 14 Charles W. Hedrick, ‘Writing and Athenian Democracy’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 7 - 11. 15 Carol Lawton, ‘Representations of Athenian Democracy in Attic Document Reliefs’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 12-16 and Olga Tzachou-Alexandri ‘Personifications of Democracy’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 149-155. 16 Peter G. Calligas, ‘The Birth of Democracy’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 17-20. 17 Alan Shapiro, ‘Pottery, Private Life and Politics in Democratic Athens’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 21-27; Alan L. Boegehold, ‘A Court Trial in Athens early in the Fourth Century’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 156-159; Dina Peppa-Delmouzou, ‘Oaths and Oath Taking in Ancient Athens’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 160-164. 9 and right to property. 18 Andrew Szegedy-Maszak considered the changing image of Athens itself in photography and political idealism in the nineteenth century. SzegedyMaszuk argues that the growing attraction of ancient Athens and the concept of ‘freedom’ for political philosophers and idealists, such as John Stuart Mill, was reflected in the image of Athens taken by photographers. The merging of image and ideology meant that classical sites in Athens, such as the Parthenon, became imbued with special meaning: A photograph, of course, can never literally depict an abstraction such as democracy. When, however, we consider photographs together with contemporary travelers’ accounts, we can see how they interacted in the construction of an ideal of Greek antiquity in which democracy played a crucial role.19 There is, however, no consideration of the meaning of these images in the 1990s and how they have become icons of Greek nationalism and capitalist democracy simultaneously. The catalogue texts on the objects displayed give a great deal of information and place them in social context with quotations and references to contemporary texts. Along with the extensive information provided by The Birth of Democracy exhibition catalogue text, the catalogue contains short scholarly articles that explore Athenian democracy and its background. While recognising that by late twentieth century standards Athenian democracy would not be considered representative or equal due to the role of slavery and the subordination of women, the catalogue celebrates the achievements of ancient Athens. Marketing and Sponsorship There is no information on exactly how the exhibition was funded from the sources at hand, but it seems that it was mainly financed through public money from the National Archives and the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, possibly though the National Endowment for the Humanities. Figures and Miscellaneous Information There is no information on the number of visitors to the exhibition from the sources at hand. The exhibition was, like the archives, free and had an extensive public education programme. Reviews Only the magazine on archaeology and antiquity Minerva reviewed The Birth of Democracy. This exhibition, though aimed at the general public, did not appear to be Jennifer Roberts, ‘Athenian Democracy Denounced. The Political Rhetoric of America’s Founders’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 164-167, p. 166. 19 Andrew Szegedy-Maszuk, ‘Athenian Democracy idealised: Nineteenth Century Photography in Athens’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 168-177, p. 169. 18 10 picked up in the mainstream media. Jerry Theodorou in Minerva did little more than comment on the appropriateness of the National Archives as a venue and listed some of the main objects on display. Gary Wills commented on the exhibition while reviewing The Greek Miracle at the National Gallery: A more plausible exhibit will be mounted by the show’s curator, Diane BuitronOliver, at the National Archives’ Building next summer, with objects directly reflecting democratic practices in ancient Athens. Meanwhile we have this, the more spectacular (though less appropriate) spectacle to be grateful for.20 In the Summer 1993 edition of Prologue, the magazine of the National Archives, two essays by Josiah Ober and Catherine Vanderpool on ‘The Birth of Athenian Democracy’ and the ‘Roots of Athenian Democracy’ appeared, as well as an article on ‘The Parthenon Stone in the Washington Monument’ by John E. Ziollowski.21 In the British publication History Today, Paul Cartledge reviewed The Birth of Democracy’s catalogue, commenting that another ‘visual celebration’ of Athenian democracy followed ‘hot on the heels of The Greek Miracle’. Cartledge considered the catalogue and exhibition to raise ‘without finally answering, hard questions about the relationship between the Athenian democracy’s political freedom for citizens’ and the high artistic achievement of Athens. Cartledge questions whether such ‘celebrations’ of Athenian democracy shouldn’t be ‘tempered’ by sober reflection on ‘cultural and political difference’ and raises the spectre of the representation of slaves, women and aliens in Athenian democracy.22 The Birth of Democracy had a greater impact in scholarship, not least because the National Archives hosted the opening of a major conference on ‘demokratia’ in Spring 1993, shortly before the exhibition itself opened. Like the exhibition, the conference was part of the ‘Democracy 2,500’ project co-ordinated by Josiah Ober and Charles Hedrick and took place at Georgetown University in Washington DC. Academics from within different areas of ancient history and classical archaeology and with a range of perspectives participated. Their papers were published in Dēmokratia: A conversation on democracy, ancient and modern in 1996: The goal of the conference was to further the project – most clearly and memorably articulated by Moses I. Finley in his seminal Democracy Ancient and Modern – of applying insights gained from political and social theory to problems in Greek history, and in turn using the historical Greek experience of democracy as a resource for building normative political theory. 23 Gary Wills, ‘Athena’s Magic’, New York Review of Books (Vol. 39, 1992), December 15 1992, 47-52, 47. National Archives’ Prologue Summer 1993 (Vol. 25). 22 Paul Cartledge, ‘The Shape of Athenian Law: Athenian Identity and Civic Ideology’, History Today (1995: Vol. 45), 45. 23 Josiah Ober and Charles Hedrick, ‘Democracies Ancient and Modern’, Josiah Ober and Charles Hedrick (eds.), Dēmokratia: A Conversation on democracy, ancient and modern (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), pp. 3-16, p. 3. 20 21 11 The resulting book was a ‘conversation’ as the papers were revised in the light of lively debates at the conference and then on the circulation of drafts among participants. Many of the scholars included in the final collection of papers from the conference also wrote essays for the exhibition catalogue – for example Jennifer Roberts and Alan Boegehold – and so there was some intellectual interaction between the participants in the conference and the exhibition. In the section on ‘Sources and Documents’ in The Birth of Democracy, next to ‘The Founding Fathers and Athenian Democracy’ section, there was a drawing of the Metroon, which housed all the records and decrees of Athens. It is described as being akin to the National Archives in Washington: The central archives building of Athens, known as the Metroon because it also housed a sanctuary of the Mother of the Gods (meter), contained thousands of documents, now lost. It stood in a central location among the public buildings of the city, next to the Bouleuterion. It overlooked the great open Agora square, just as the National Archives overlooks the Mall in Washington, D.C.24 The National Archives holds the documents and archives of American governance including key documents from the formation of the constitution and the War of Independence. It also holds documents relating to slavery, immigration and war records and evidently is key place for people researching their family history. The National Archive’s motto for its National Archives Experience is ‘Democracy Starts Here’, which was launched in 2003 and ‘greatly expands the opportunity or vision to be inspired and enlightened by the original documents of our democracy’. 25 An eleven minute video downloadable on the internet (sponsored by Discovery Channel) introduces the Archives as being created by the people for the people. 26 The video presents the Archives as preserving democracy through preserving the archives of government as well as keeping the story of America alive through its display of the ‘documents of freedom’, such as the Bill of Rights. Combined with these monumental historical moments and documents are the stories of people who have researched their family in the archives and discovered abuses of their freedoms, such as the internment of Japanese-Americans in World War Two. The video says the role of the archives is to keep a clear paper trail so if the nation makes a mistake that wrong can be amended. There is no mention of Athenian democracy, nor should it be expected, but the line ‘Democracy Starts Here’ echoes the sentiments expressed in The Birth of Democracy exhibition held at the National Archive ten years before the development of the ‘Democracy Starts Here’ National Archives Experience. 24 Diana Buitron-Oliver and John Mck. Camp II, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), p. 143. 25 The National Archives Experience Exhibit Guide leaflet, National Archives Washington DC. 26 ‘Democracy Starts Here’, http://videocast.nih.gov/sla/NARA/dsh/index.html [accessed 01/07/2008] 12 Bibliography Boegehold, Alan L., ‘A Court Trial in Athens early in the Fourth Century’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 156-159. Buitron-Oliver, Diana and Mck. Camp II, John, ‘Introduction to the Exhibition’, Josiah Ober and Charles W. Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy. An Exhibition Celebrating the 2,500th Anniversary of Democracy (Washington DC: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1993), pp. 29-35. Calligas, Peter G., ‘The Birth of Democracy’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 17-20. Cartledge, Paul, ‘The Shape of Athenian Law: Athenian Identity and Civic Ideology’, History Today (1995: Vol. 45), 45. Coulson, William D. E., ‘Introductory Remarks II. Athens and America’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), p. 4-5. Dyson, Stephen L., In Pursuit of Ancient Pasts. A History of Classical Archaeology in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Yale: Yale University Press, 2006), p. 219. Hedrick, Charles W., ‘Writing and Athenian Democracy’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 7 - 11. Lawton, Carol, ‘Representations of Athenian Democracy in Attic Document Reliefs’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 12-16. National Archives’ Prologue Summer 1993 (Vol. 25). Ober, Josiah and Hedrick, Charles, ‘Democracies Ancient and Modern’, Josiah Ober and Charles Hedrick (eds.), Dēmokratia: A Conversation on democracy, ancient and modern (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), pp. 3-16. Ober, Josiah, and Hedrick, Charles W. (eds.), The Birth of Democracy. An Exhibition Celebrating the 2,500th Anniversary of Democracy (Washington DC: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1993). Ober, Josiah,‘Introductory Remarks I. The Athenian Revolution’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), p. 1-3. Peppa-Delmouzou, Dina, ‘Oaths and Oath Taking in Ancient Athens’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 160-164. Roberts, Jennifer,‘Athenian Democracy Denounced. The Political Rhetoric of America’s Founders’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 164-167. Romiopoulou, Katerina, ‘Introductory Remarks II. Democracy and Freedom’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), p. 6. Shanks, Michael and Tilley, Christopher, Re-constructing Archaeology: Theory and Practice (London: Routledge, 1992). Shapiro, Alan, ‘Pottery, Private Life and Politics in Democratic Athens’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 21-27. Szegedy-Maszuk, Andrew, ‘Athenian Democracy idealised: Nineteenth Century Photography in Athens’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 168-177. Theodorou, Jerry, ‘The Birth of Democracy. 2,500th Anniversary celebrated in an exhibition in Washington DC’, Minerva, July/August 1993 (Vol. 4, No. 4), 16-17. Tzachou-Alexandri, Olga, ‘Personifications of Democracy’, Ober and Hedrick (eds.), The Birth of Democracy (1993), pp. 149-155. 13 Wills, Gary, ‘Athena’s Magic’, New York Review of Books (Vol. 39, 1992), December 15 1992, 47-52. Websites The Birth of Democracy: An Exhibition Celebrating the 2500th Anniversary of Democracy, on the Excavations in the Agora website, http://www.attalos.com/cgibin/text?lookup=democracy;id=Contents (accessed 11/06/2008) ‘Democracy Starts Here’, http://videocast.nih.gov/sla/NARA/dsh/index.html [accessed 01/07/2008] 14