UNESCO Man - Paper - San Francisco 2008

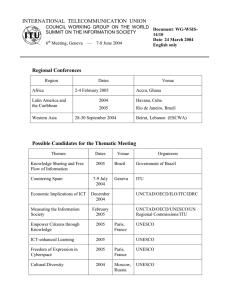

advertisement