A review of the needs of students with ADHD in Trinity College Dublin - June 2010

A review of the needs of students with ADHD in Trinity College Dublin

Declan Reilly & Kieran Lewis

Disability Service

University of Dublin Trinity College

June 2010

Seirbhís do dhaoine faoí mhíchumas,

Seomra 2054,

Foígneamh na nEalaíon

Coláiste na Tríonóide,

Baile Átha Cliath 2, Éire

Disability Service,

Room 2054, Arts Building,

Trinity College,

Dublin 2, Ireland

1

Contents

1. Abstract

2. Introduction and Background

3. The profile of students with ADHD at Trinity College 2000 to 2009

4. Comparison of grades between ADHD & Non-ADHD Students

5. Retention rates for students with ADHD

6. The medical perspective

7. The specific educational impacts

8. Personal statements from the CAO

9. Educational impacts reported in the Trinity Student Profile

10. The social model & neurodiversity

11. Rationale for existing supports and accommodations

12. Development of ADHD specific supportsRationale for ADHD specific supports

13. Conclusions & recommendations for future work

References and Bibliography

Appendices

2

1. Abstract

Research indicates a dramatic increase in students with disabilities attending 3 rd level education, from 1,350 in 1998 to almost 5,000 in 2009, Ahead (2010). In line with this, the numbers of students with ADHD attending 3 rd level education in Ireland have dramatically increased in the past 5 years. In Trinity College the numbers of students registering with the Disability Service have increased from less than 5 in 2005 to 18 in

2009. Making the transition from secondary school to college can be especially difficult for this student group. There is a lack of sufficient knowledge and targeted resources to adequately respond to the growing numbers and complex needs of this group of students. Support services have struggled with the range of difficulties and the increasing number of students presenting with ADHD symptoms. This paper will outline the current approach used to support students with ADHD within Trinity College and explore future interventions. We have categorised the supports we offer under the following headings:

Inclusive curriculum and management of workload

Self Management

Environmental adaptations

ADHD Education and appropriate referral

Orientation to college environments and systems.

We propose that through the appropriate provision of supports within these areas, students with ADHD can successfully engage with college and prepare for their future.

2. Introduction & Background:

The primary purpose of this paper is to focus on the support needs of students in Trinity

College who present with ADHD. Despite the Disability Service being 10 years old, it is fair to say that as a service we have only recently recognised students with ADHD as an emerging group with their own distinct set of difficulties. A secondary purpose of this paper, therefore, is to set out how the Disability Service has responded to this emerging group and what work can be done in the future to accommodate the needs of students with ADHD. Essentially, this paper is part report and part work plan. What follows

3

reflects the experience of the Disability Service over the past 5 years in supporting students with ADHD and what areas have been identified where more work is needed.

In general, following medical and diagnostic symptoms, initially ADHD was seen and treated as a mental health difficulty. However, from an educational point of view, ADHD is often seen as a specific learning difficulty (SPLD). This conceptual ambiguity in framing ADHD is important to emphasise because until recently supports for students in this group were based on what worked for other students; with either a mental health difficulty such as depression, or a SPLD such as dyslexia. But as the numbers of students with ADHD have increased, especially over the last two years, it has become increasingly apparent that more specialised forms of supports are required.

3. The profile of students with ADHD at Trinity College 2000 to 2009

Globally, the prevalence of ADHD in the childhood population is considered to be between 1% and 5%. In Ireland, this means that the number of children in Ireland under 14 with ADHD could be up to 40,000 and in the older group aged 15 to 24 it could be up to 31,000. About 30%-50% of children referred to child psychiatry clinics have

ADHD. It is diagnosed in boys 3-4 times more often than in girls. ADHD symptoms persist for up to 60% of individuals into adolescence and adulthood (although the symptom profile may change). The prevalence in adults is estimated at about 2%.

According to the 2006 census there were 143,000 students in 3 rd level in the academic year 04/05. Just 1% of this is 1,430 and 5% is 7,177. But nothing close to these figures are presenting with ADHD at present, although the figure are set to rise significantly.

Between 2000 and 2005 less than 5 students with ADHD had registered with the

Disability Service in Trinity College. In the next two years another 5 registered. In

2008 there were 9 more students registered with ADHD and in 2009 there were an additional 11 students. In total, 25 students have registered since 2005 but significantly the rate has increased from less than 1 a year from 2000 to 2005 to a rate of 10 a year for 08/09. If this rates stabilises then by 2012 there will be between

40 to 50 students with ADHD.

4

3.1 Increase in students with ADHD registering with the Disability Service

3.2 Increase in students with ADHD attending 3 rd level education in Ireland

3.3 Disclosure of ADHD through CAO and DARE

Applicants to 3 rd level education from students with ADHD have significantly increased over the last 4 years. In 2006, 18 students disclosed ADHD on their CAO application.

In 2007 this figure increased to 27 students, to 40 in 2008, and 92 in 2009. The figures for 2010 indicate that 82 students have disclosed ADHD through their DARE

5

application. The latter figure indicates that perhaps a levelling off has been reached.

However, as the criteria for ADHD may change in the DSM V in 2011, this may bring about significant changes to the current rates of diagnosis in Ireland. The proposed changes are outline in Section 6 below.

3.4 Status of students

Of the 25 students with ADHD who have registered with the Disability Service since

2005;

6 have graduated

4 are in their final year

5 are in third year

3 are in second year

6 are in first year (this includes 2 Post Graduates)

1 student has withdrawn

6

Typically there are no surprises in the age and gender of students with ADHD.

They are predominantly male aged 18 to 24. Of the 25 students with ADHD who have registered with the Disability Service since 2005, 17 are male (68%) and 8 are Female (32%). This is a ratio of 2:1, Male: Female. Internationally the prevalence of males to females with ADHD is around the 4:1 ratio. However, it is widely accepted that ADHD is under diagnosed in females. Also, in TCD the student population is 44% male and 56% female so this may account for some of the apparent gender discrepancy.

3.5 Age range, faculty, entry route & level of students with ADHD registered with the Disability Service

Breakdown by age

19 - 21: 8

22 – 24: 8

25

– 26: 4

26 – 30: 1

30 - 35: 0

36

– 45: 4

7

Breakdown by Faculty

Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences: 18 (including 6 TSM)

Engineering, Maths and Science: 4

Health Sciences: 3

Breakdown by Entry Route

Merit: 18

Supplemental: 5

Mature: 2

Ratio of Undergraduate to Postgraduate

Undergraduate: 22

Postgraduate: 3

8

4. Comparison of grades between ADHD & Non-ADHD Students

Figures from the TCD website indicate that 52.2% of CAO entrants to TCD had 500 points and above in 2008. Out of 23 students with ADHD 18 got into TCD by meeting the points requirement for their course. However, the following grade record indicates that perhaps students with ADHD are lagging behind their peers when it comes to achieving grades when they get here. We can only say ‘perhaps’ because the sample of

25 is not large enough to be statistically significant. However, it is evident that when only 16% of a student group are achieving a grade of 2.1 or above compared to 67%, it is an area worth looking more closely at in future.

ADHD Students no. %

Non-ADHD Students no. %

1 st

2.1

2.2

1

3

6

4

12

24

330

1144

506

15

52

23

Pass

Pass PG

Fail

Yet to do exams

Withdrawn

Total:

6

2

1

5

1

25

24

8

4

20

4

100%

198

0

0

0

22

2200

9

0

0

0

1

100%

5. Retention rates of students with ADHD

In contrast to grades where there is some indication that students with ADHD are performing significantly lower than their peers, it is noteworthy that as a group they are more likely to remain in College. The retention rate for the 25 students with ADHD is

92% compared to the overall College rate of 84.5%. As with grade comparison it is important to remember that a group of 25 is not large enough to be statistically significant. In addition, the percentage rates are far closer in comparison to the rates of

9

grades achieved. Despite these clarifications there is a strong sense that students who are supported are less likely to withdraw from College, even if they are not achieving grades as high as their peers, Seidman (2005). As this tendency appears throughout the student with a disability population it should be relatively simple to objectively compare grade and retention rates. At present, our own data indicates

Did not complete:

ADHD Students no.

2

%

8

Non-ADHD Students no.

341

1859

%

15.5

84.5 Did or are yet to complete: 23

Total: 25

92.0

2200

6. The medical perspective of ADHD

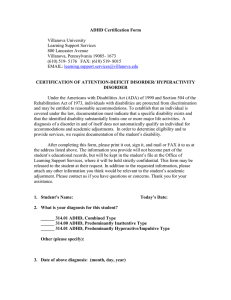

Although we are a student service operating in a university and our primary aim is in supporting students to reach their academic goals, we our dependent on the medical model of disability for the legal and financial backing which that brings. In supporting students with ADHD this is no different. To recognise a student as having ADHD we must insist that a consultant psychiatrist or clinical psychologist has provided the diagnosis and followed the criteria in the DSM IV or ICD – 10. Adhering to this criteria allows applicants to 3 rd level education eligibility for DARE and successful entrants, funding through the ESF. The full criteria of the DSM IV are listed below in appendix 1.

The DSM V is due to be published in 2011 and there are 3 proposed changes for the criteria to ADHD:

1) A change of the 3 subtypes as were developed in the DSM IV to 4 subtypes.

2) A change of age of onset from age 7 to age 12.

3) Fewer symptoms required for diagnosis in adult ADHD, down from 6 criteria to 4 for those aged 17 and older. See appendix 2 below. The 2010 criteria for DARE are in appendix 3. If these proposed changes for the DSM V are brought in and applied it will most likely lead to an increase in the rate of diagnosis. This will be particularly the case in Ireland where it is already considered that ADHD is underdiagnosed.

10

7. The specific educational impacts of ADHD

Inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity are widely regarded as the core symptoms of

ADHD. In adulthood, these symptoms are strongly associated with disorganisation, poor-time-management and inadequate problem-solving skills. (Bramham & Young,

2009). Over the past decade, increasing research has being carried out to establish the functional implications of ADHD within the college cohort. Reaser et al (2007) using the

Learning and Study Strategies Inventory (LASSI; Weinstein & Palmer, 2002), compared the scores of students with ADHD, students with other specific learning difficulties and students without a learning difficulty. They found that students with ADHD scored lower than the students from the other two groups in the areas of time management, concentration, selection of main ideas, and test taking strategies.

Lewandowski, Lovett, Codding, and Gordon (2008) compared self-report ratings regarding ADHD symptoms, academic functioning and text-taking concerns from students with an ADHD diagnosis and students without ADHD. Students with a diagnosis of ADHD not only reported more frequent symptoms of the disorder but also greater problems with academic functioning. Problems included struggles with timed tests, lack of test completion on time, longer duration to complete assignments, and the perception of working harder to achieve good grades.

Norwalk et al. (2008) suggest that ADHD symptoms are negatively correlated with levels of study habits, study skills, and academic adjustment.

Parker & Benedict (2002) claim that executive function impairments associated with

ADHD can give rise to a variety of functional limitations for postsecondary students, including difficulty developing realistic plans, activating and sustaining effort across time, remembering goals, and regulating intense emotional reactions to daily frustrations.

8. Personal statements from the CAO supplementary form

My disability (ADHD) has made concentrating in class and at home very difficult.

My grades have been affected because of my failure to reach deadlines or

11

complete work due to lack of concentration. Though this situation has improved since I began receiving learning support I still find school to be a stressful environment. I think my disability prevents me from using my full potential and I believe my work is of a lower standard than I am capable of. I also think my confidence in m schoolwork has been lowered significantly and therefore has reduced my willingness to participate in class.

This statement is typical of the 75 personal statements from applicants who disclosed

ADHD on their CAO forms in 2009. We identified general areas of academic and nonacademic difficulty from 75 statements. The issues and numbers of students who reported these difficulties associated with their ADHD are outlined below:

Reported Difficulty

Inattention / Memory

Number (n=75)

57 (76%)

Poor Organisation /Planning / Time Management 22(29.33%)

Impulsivity

Reading difficulties

4 (5.33%)

9 (12%)

Writing difficulties

Dyspraxia

Other Mental Health

Dyslexia

13(17.33%)

4 (5.33%)

1 (1.33%)

6 (8%)

Due to ADD I have poor organizational skills. Although I spend a lot of time trying to get organized, I tend to procrastinate and never seem to catch up which is very frustrating. I have great trouble concentrating for even a short period. I have to keep trying to bring my mind back to the task in hand. In an exam situation I find it very hard to work in a room full of people without being distracted. I feel that I have to work harder than everyone else and then when it comes to exams I don't do as we as I should. I have a problem with time. It takes me much longer than other people to read. I often have to reread things. I run out of time in exams, although I know the answers to the questions. In test situations I get stressed.

Sometimes I misinterpret questions and underperform. This is very disappointing as I know I have worked hard and should have done well.

12

9. Educational impacts reported in the Trinity Student Profile (TSP)

The Trinity Student Profile is an assessment of a student’s function in their various college contexts. On the TSP, students identified areas of difficulty on a scale from 0-5, with 0 being no difficulty in that area and 5 being great difficulty in that area. For the purposes of identifying the areas of difficulty experienced by students with ADHD, we show the areas where students most frequently chose either 4 (moderate difficulty) or 5

(great difficulty). These areas were as follows;

Area of Difficulty No. of Students who identified moderate or great difficulty (n=19)

Concentrating during lectures

Maintaining concentration during study

Maintaining good mental stamina / endurance

Handing up work on time

11 (57.9%)

13 (68.4%)

11 (57.9%)

14 (73.7%)

15 (78.9%) Dealing with time pressures and deadlines

Dealing with work overload

Knowing how best to study

Getting started with Study

Goal Setting

13 (68.4%)

12 (63.1%)

13 (68.4%)

10 (52.6%)

Achieving Goals

Organising Information

Structuring and planning the essay

Finishing the work

Writing study notes

Balancing college and work life

14 (73.7%)

11 (57.9%)

11 (57.9%)

12 (63.1%)

10 (52.6%)

10 (52.6%)

The difficulties most frequently identified by the students who completed the TSP appear consistent with the findings of the research outlined above. Both day to day time management and planning of workload across terms and academic years appear

13

to be a challenge for the students within this group. Maintaining concentration in both study and in the lectures also appears to be difficult for these students.

10. The social model and neurodiversity:

While the DSM IV sets out the diagnostic criteria for what is classified as ADHD and the medical perspectives of genetics, neuroscience, psychiatry and pharmacology continue to both research and treat the respective causes and symptoms of ADHD; this ‘medical model’ of disability is not the only valid perspective to consider.

The social model of disability has its roots in the civil rights move ment of 1960’s

America. Adapted in the United Kingdom in the 1970’s most notably by the Union of the

Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) and subsequently by other disability groups and by writers such as Oliver (1990) and Shakespeare (2002), the social model of disability asserts that it is society that is largely responsible for creating disability by constructing barriers in the environment. While acknowledging to varying degrees that physical, sensory and cognitive functioning can be impaired by the physical limitations of the body; the social model of disability states that it is often only an environmental or societal barrier that ultimately disables people.

If the medical and social models of disability represent a thesis and antithesis in dealing with the phenomenon of ‘learning difficulties,’ then the concept of neurodiversity could be the synthesis that finally leads to a breakthrough in our understanding of learning difference. Armstrong (2010) in a recently published book on neurodiversity argues that the human brain is far more complex and diverse than previously thought and that all behaviours and learning styles occur on a continuum. In a world where ‘brain’ diversity is vital so that new adaptations can be made at speed; people who think, talk, act and learn differently should be valued and facilitated. The term was first published by Judy

Singer; ‘‘For me, the key significance of the ‘Autistic Spectrum’ lies in its call for and anticipation of a politics of Neurological Diversity, or what I want to call ‘Neurodiversity.’”

(Singer, 1999).

Looking at ADHD from the paradigm of neurodiversity it should come as no surprise

14

that some people will have different thresholds of tolerance for the low level stimulus of boredom, inaction, solitude and silence; and for the high level stimulus of frantic activity, rapid visual change, crowds and excessive background noise. In many learning environments these thresholds are often ignored or poorly controlled with the result that some people will be unable to function effectively.

The legitimacy of both the social model of disability and the perspective of neurodiversity is that the right environment can effectively return an individual to the point where they can function effectively once more. Regardless of the genetic, biochemical or neurological causes of ADHD and regardless also of whether or not medication is used; the perspectives of the social model of disability and neurodiversity are pivotal in identifying and removing environmental barriers in the educational setting.

11. Rationale for existing supports & accommodations

Until recently the rationale for specific methods of intervention carried out in TCD and all other HEIs by the Disability Service for students with ADHD tended to be based on what supports and accommodations were commonly provided to students with mental health difficulties and students with dyslexia. In most cases and to some considerable extent these supports worked well enough. Typically these supports included:

With the student’s consent, dissemination of a LENS report outlining specific learning needs and suggested accommodations to relevant tutor and department.

The provision of extensions on coursework.

Provision of notes before lectures

Use of scribes within lectures and tutorials.

Material in alternate format

The use of Assistive Technology

Subject specific tuition

Extra time in exams

Photocopying /Printer cards

Referral to Unilink Occupational Therapy Support Service

15

12. Development of ADHD specific supports

However, as the numbers of students with ADHD increased over the past 2 years, and we gained a better understanding of the specific areas that students with ADHD were experiencing difficulty in, it became ever more apparent that more specialised forms of support and intervention were required in addition to the baseline supports on offer to other students. Adopting both the social model of disability and the concept of neurodiversity it was clear that greater emphasis was needed in looking at the interaction of the individual student, their environment and the activity they were involved in. To this end the PEO Model (Person-Environment-Occupation) was introduced by the Occupational Therapy led support service (Unilink), to identify and develop specialised supports and to implement them.

Unilink is a confidential, Occupational Therapy based support service for students who may be experiencing mental health difficulties, including those with ADHD and AS. It is a student-centred, college based service which offers support directly through face to face meetings or indirectly through phone, text or email. During the one-on-one meetings, the student and Occupational Therapist collaboratively work to develop practical strategies within the PEO framework to help them fulfill their role as a student.

The PEO Model allows therapists within the Unilink Service to address complex interactions between the person and their environment and to address their participation and engagement in activities, tasks and roles that are meaningful to them. The focus of this service is upon the occupational competence of the individual, in other words, the therapist focuses upon engagement in activities that promote health and well being and that have value for the individual. An important belief of this model is that people are naturally motivated to explore their world and demonstrate mastery within it. An individual’s ability and skill to do what he or she must do in order to meet personal needs is measure of his or her competence. To do this a person must effectively use the resources (personal, social and material) available within the living environment. A second belief of this model is that situations in which people experience success help them feel good about themselves. This motivates them to face new challenges with greater confidence. The model proposes that through their daily occupations people develop a self identity and derive a sense of fulfilment. Fulfilment comes both from

16

feelings of mastery as well as the accomplishment of goals that have personal meaning.

Over time, these meaningful experiences permit people to develop an understanding of who they are and what their place is in the world. (Baum, C. M. & Christiansen,

C.H.(2005)

13. Rationale for ADHD specific supports

As mentioned above, the approach to date has been centred on environmental accommodations which focused on helping students to manage some of their cognitive deficits. However, although this makes intuitive sense based upon some of the difficulties experienced by students with ADHD highlighted above, this approach has not received extensive empirical scrutiny (DuPaul, Weyandt, 2009). However it must be noted that depriving students of these accommodations as part of a control group, to provide this empirical data, may not be feasible.

Under the 5 identified headings of inclusive curriculum / management of workload, self management, environmental adaptations, education and appropriate referral and orientation to college environments and systems, we will examine the rationale for the

ADHD specific supports we are proposing.

14.1 Inclusive Curriculum / Management of Workload (Occupation)

1. Continue the existing support of providing one-on-one course specific tuition as it is an effective way to allow students to review course material, as they may have difficulty learning within lectures and tutorials as a consequence of their concentration difficulties.

This type of support should be provided in conjunction with learning support to facilitate the development of generic academic skills such as note taking and essay writing.

2. Continue, through the use of the LENS report, the tutor system and if necessary direct liaison with the department, the provision of extensions to course work across the academic year.

17

3. Provide, where possible, course material that is presented through a variety of accessible methods, so that students with various learning styles can engage with it. It is essential that multi-sensory teaching methods are used because these are more likely to suit a variety of learning styles. Lectures should be presented in a way that uses the visual, auditory, and kinaesthetic modes. Access to lecture notes or podcasts online, or the opportunity to record lectures using digital recorders provides the student an opportunity to go through the content in an environment and at a pace that is suited to their learning style.

4. Provide individual meetings by appropriately trained staff to facilitate the identification of specific course demands, prioritisation of workload, application newly learned academic skills, breaking down of workload, and development of a productive routine.

Students with ADHD have identified the accountability provided to students through a process of goal setting and reviewing within this type of support as an important coping strategy. (Meaux, Green and Broussard, 2009). We propose that using regular, short individual meetings, at flexible times around the student’s timetable is an effective method in helping the student to ach ieve these goals. The use of individual ‘coaching’ is offered by many colleges in the United States for students with ADHD, with initial research showing positive outcomes. (Parker & Boutelle, 2009; Swartz, Prevatt, &

Proctor,2005; ) DuPaul et al. (2009) claim however that no empirical studies beyond qualitative reports of individual case studies could be found to support the use of coaching. Many courses change in structure over the final two years, involving less direct lecture and tutorial hours but demanding a more self-directed learning style.

Longer essays and research projects demand higher levels of planning and structuring of time. We propose that the provision of short and regular meetings to break down the workload, incorporating a goal based approach as outlined above could prove useful in meeting the academic demands of these final years.

5. Another method of providing focus and accountability is to utilise peer support through the use of study groups or a study partner. This also provides a more interactive and engaging method of learning which may prove useful to students with

ADHD. Meaux, Green and Broussard (2009) highlight that the students with ADHD within their study group identified peer-relationships as a particularly helpful coping

18

factor.

Specific supports for inclusive curriculum and management of workload:

Podcasting of lectures where possible.

Education of teaching staff and tutors in the area of ADHD and ideas for teaching methods;

-

Consistent lecture plans

-

Written outlines of lecture plans

-

Accessible format of material

-

Limited material on slides

-

The provision of templates for assignments online

-

Clear reading lists

-

Written instructions of assignments at the end of lecture, emailed or on Webct.

-

The use of variety a teaching modes, suitable to various learning styles

Further uses of AT;

-

Use of phone alarms set at 10 minute intervals to remind the student to re-focus

-

Screen rulers

-

Changing the background of screens to suit visual stimuli thresholds.

Study Groups / Study Partner – if possible utilise peer support to provide structure and accountability to maintain workload.

Individual Unilink support a. Short meetings at flexible times b. Prioritisation of workload c. Breaking down workload into manageable steps d. Goal-setting e. Accountability in achieving these goals f. Development and application of study skills

19

g. Opportunity to practice using study skills within meetings rather than a purely didactic approach. h. Individual problem solving i. Support in accessing other college based supports j. Identifying individual course demands and support in applying above strategies to meet them. k. Face to face, email and text contact with the student as appropriate. l. Organisation of materials, notes etc.

14.2 Self Management (Person)

For many students, coming to college is the first time that they have to take full responsibility for their self-management. Prior to this point, students have come from heavily supported environments both at home and school. Reminders from parents, siblings, teachers, regular daily schedules, relatively small group sizes and daily checking of homework and attendance are all systems in place at this time. In describing this phenomenon, Katz (1998) observed that the ADHD brain “uses the external stimulus to focus or sustain attention as a substitute for its own disregulation of the mechanisms which mediate the attentional process, whether selective, sustained or inhibitive.

” (p. 3)

As students transition to the postsecondary education, greater demands are placed on their internal capacity to organize goal-directed behavior. Faced with this environment, which provides much less external structure, many individuals with ADHD encounter an intensified need for support services. (Parker & Boutelle, 2009)

Helping students to develop the ability to manage their daily lives in support of their various roles, although important for all students, is particularly pertinent for students with ADHD and who are new to the college environment. Many students may have moved away from the established support structures of friends and family.

As outlined in the above sections, possibly due to the individual’s attentional and

20

executive functioning difficulties, poor time management and organisation skills become particularly prominent within the unstructured college context. The lack of regular deadlines and self-directed nature of many courses, especially in the later years of college, prove particularly difficult for students with ADHD. The use of various forms of assistive technology, such as electronic reminders can be very beneficial for individuals with ADHD.

Integrating socially into the college environment is often extremely challenging for students with ADHD. Shaw-Zirt, Popali-Lehane, Chaplin and Bergman (2005) found that college students exhibited lower levels of adjustment, social skills, and self-esteem as compared to a matched control group. Grenwald-Mayes (2002) found that students with ADHD experience a lower quality of life relative to their non-ADHD peers. It is important to facilitate the student to integrate into the social fabric of college through practical social skills work, problem solving and engagement in leisure activities within college. Substance use has also been identified as a possible problem area for this group. It has been found that students, who actively display symptoms of ADHD, are more likely to engage in substance use than students without current active symptoms.

(Upadhyaya et al., 2005)

Specific self management supports:

Individual Unilink support;

Management of basic needs – diet, substance use / misuse, finances etc.

Medication – Compliance with medication may need to be addressed.

Social skills training and development of leisure interests.

Identifying everyday occupations that the student must engage in to meet the demands of their various roles.

Developing occupational balance within routine.

Support in developing and applying self management strategies to various contexts within and outside college.

Time Management

– scheduling / term planning / developing a

21

productive routine / Use of AT (Electronic reminders, Google

Calendar etc.)

If necessary, support through course transfer / withdrawal process.

Education around individual sensory needs and application of strategies to manage these. Strategies may include:

Sitting in the front of lectures to reduce distractions

Using earplugs / earphones to block out auditory stimuli

Identify activities that provide sensory input to help the student to modulate their level of alertness.

Taking breaks from situations that are over-stimulating such as lectures, busy canteens or coffee shops, or buses / trains.

Taking earlier buses / trains or walk /cycle to avoid crowded areas.

Arrive early to lectures / tutorials to avoid crowded stairways.

14.3 Environmental adaptations (environment)

Recent research studies have provided evidence of the association between dysfunction in sensory modulation and ADHD (Mangeot et al, 2001, Dunn and Bennett,

2002). Sensory modulation is the capacity to regulate and organise the degree, intensity, and nature of responses to sensory input in a graded and adaptive manner, so that an optimal range of performance and adaption to challenges can be maintained

(Lane et al. 2000). Sensory Modulation Disorder (SMD) presents with responses that are inconsistent with the demands of the situation, and an inflexibility in adapting to sensory challenges encountered in daily life, leading to difficulty achieving and maintaining a developmentally appropriate range of emotional and attentional responses. (Miller et al., 2007).

Mangeot et al.(2001) propose that a subgroup of individuals with ADHD also have a sensory modulation disorder. Miller et al. (2007) highlight that the hyperactivity and impulsivity associated with some types of SMD can easily be confused with, but also often co-occur with ADHD. Because of their heightened sensitivity to sensory stimulation, some adults with ADHD are particularly prone to both sensory over- and

22

under-load. They may be highly sensitive to sensory input such as light, noise, temperature, tactile sensations, odours, and strong tastes. (Gutman, 2005). Some individuals may require certain types of sensory input, for example some types of strenuous exercise, to help modulate this sensory over- or under-load, to allow them to engage in their desired occupations.

For a student who is sensitive to certain sensory input, adjustment to the postsecondary education setting may involve functioning in a much more stimulating environment than they are used to, including larger classes; coping with an unfamiliar roommate; and living in a residence hall. (Johnson & Irving, 2008) If avoidance and predictability were coping strategies previously used, a student sensitive to sensory stimulation may find them harder to use or ineffective in this novel setting (Kinnealey et al, 1995). Students who were once able to cope and adjust to a changing sensory environment may now find coping more difficult, which could lead to exacerbation of feelings of depression and anxiety (Johnson & Irving, 2008). As they get older, students may become more aware of a mismatch between their own sensory integration characteristics and societal norms, leading to low self-esteem, limited social participation and dissatisfaction with quality of life. (Kinnealey et al, 1995; Pfeiffer, 2002)

If identified during assessment, based upon the Adolescent / Adult Sensory Profile

(Brown & Dunn, 2002), we propose the use of activities which provide certain sensory inputs, based upon Sensory Integration Theory in addition to the use of strategies to help manage various sensory environments in college. We suggest a combination of adaptations to sensory environments, where possible, as well as the use of individual sensory management strategies Educating the individual about their sensory needs is important in helping them to develop the ability to manage various sensory environments such as libraries, common areas, lecture halls, crowded stairways, coffee shops and exam halls.

The provision of a distraction-free study environment is an accommodation regularly suggested for students with ADHD. We suggest that this may be appropriate for some students but not all. Some students require complete silence while some will study better with some background noise. Some students study best in a dimly lit

23

environment, while others require a high level of lighting. Having a study space in which the student can control the amount of sensory stimulation (noise, light, temperature etc.), allows students who are sensitive to sensory input to create a suitable environment. Study spaces such as these would also prove effective for students with ADHD who do not have a SMD, as it would allow them to create a study space suitable to their individual needs learning needs.

We also suggest the provision of smaller distraction free exam venues, which is another accommodation commonly offered by colleges to students with ADHD, but we propose that an increased awareness of what type of sensory environment these smaller venues are, is required. Is the student who is sensitive to noise taking an exam in a venue beside a busy road or is there a ticking clock or buzzing light in the venue? Is the venue cluttered with academic materials? Is the lighting appropriate? An unde rstanding of the student’s sensory needs is important for both the student and college to have.

Specific environmental adaptations:

The provision of study carrels or separate study rooms.

The provision of distraction free exam venues based upon students ’ sensory needs.

Advice on setting up study space at home:

Appropriate to sensory needs

Removing distractions (computer, radio, t.v.,clutter)

Organising materials

14.4 Education and appropriate referral

Many students entering college may already have a diagnosis of ADHD and have become accustomed to their possible difficulties, and may have developed effective coping strategies. Some students however may only receive a diagnosis when they come to college. The process of providing information and discussing possible academic and non-academic functional implications as a result of ADHD is important for

24

students with a recent diagnosis. If there are possible sensory processing issues as discussed earlier, then helping the student to develop an understanding of their sensory needs is also necessary in developing their ability to function within the college context.

In interviews carried out by Meaux, Green and Broussard (2009) students with ADHD identified four factors that helped them gain insight about their difficulties. They were:

(1) learning through experience; (2) seeking information; (3) acknowledging their ADHD; and (4) opening up. Often students react with a sense of relief when they receive a diagnosis of ADHD as it helps them gain an understanding of why they experience difficulty in certain situations. As Bramham & Young (2009) claim it is important to help the student to understand that although there is no ‘magic cure’ for ADHD, it is possible to change how they cope with it and to maximise specific strengths that they have.

The link between ADHD and other mental health difficulties is now well established.

Studies have shown a range of co-morbid conditions associated with ADHD such as bipolar disorders (Bernaldi et al., 2009; Halmoy et al., 2009), anxiety (Edel at al., Dineen

& Gallagher, 2009), oppositional and conduct disorders (Alvaani and Dalvand, 2009;

Franc et al., 2009), and autism spectrum disorder (Dineen and Fitzgerald, 2009; Roy et al.,2009; Sinzig et al. 2009) (from Thorne and Reddy, 2009). Education around these mental health difficulties and management of functional problems that the student may be experiencing as a result of a these difficulties, is essential in facilitating the student to engage in their chosen occupations. This can be done through the established mental health support services within Unilink, the college health centre and the student counselling service.

Specific education / appropriate referral supports:

Education in the area of ADHD and its possible functional implications.

Education in other possible mental health or specific learning difficulties and development of self-management strategies related to functional difficulties associated with them. This can be done through Unilink.

Appropriate referral to other Disability Service Staff, Counselling, and College

Health services.

25

14.5 Orientation to college environments and systems

As outlined above the transition from the supported and structured environments of secondary school and home to college can prove difficult for students with ADHD.

Trinity is a very large establishment with many different physical environments, administrative departments, academic and non-academic support services and IT systems. The college offers orientation programs during the weeks leading up to the start of term, but we suggest that individual orientation, specific to the student’s course, relevant supports and interests, would prove useful in helping students with ADHD to integrate into college. For many students, this will be the first occasion that they will be advocating for themselves to various departments and some may need to be supported through this process.

Specific supports for orientation to college environments and systems:

Orientation to physical environments such as libraries, lecture theatres, administration offices and social settings around college.

Connection to support services – academic / non-academic

Instruction on IT services and course specific websites

Support in accessing college support and administration systems through development of advocacy and assertiveness within Unilink.

26

14. Conclusions and recommendations for future work

The TCD Disability Service have developed significantly in the past 10 years. A consequence of the success of access initiatives such as DARE is that far more ‘non traditional’ students are entering 3 rd level education. The Disability Service are aware of the need to comply with Equality and Disability legislation; and to uphold academic standards and College regulations. Utilising the medical perspective is essential for these purposes. But a service based only on the medical model of disability would be hopelessly inadequate. By focusing on the needs of the students who present themselves for support we must take pragmatic steps to provide reasonable accommodations. The social model of disability allows us to support students by solving problems that exist in the interaction between neurodiverse students, complex environments and highly specialised tasks. The Unilink service provides a vehicle for this problem solving and we have identified 5 specific areas for further development in the provision of supports for students with ADHD. As is illustrated in this paper, research is ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of some of the approaches used to support students with ADHD. The Disability Service are currently implementing the above proposed supports and accommodations and will be evaluating their effectiveness over the foreseeable future.

The empirical study of ADHD in the college student is in its infancy compared to the vast body of literature concerning ADHD in children and adolescents (DuPaul et al.,

2009). In addition, studies are needed to determine whether educational accommodations offered to students with ADHD are truly effective and whether some interventions are more effective than others. This paper has outlined the profile of and the significant academic data relating to students with ADHD in TCD. The types of supports offered to students with ADHD within the Disability Service have been discussed and the areas where more work is required have been identified.

27

References:

AHEAD http://www.ahead.ie/inclusiveeducation_accessingthirdlevel.php

(accessed

May 11th 2010).

Armstrong,T. http://www.newhorizons.org/spneeds/inclusion/information/armstrong.htm

(accessed

May 11th 2010).

Baum, C.M.& Christiansen, C.H. (2005) Person-environment-occupationperformance: An occupation-based framework for practice. In C. H. Christiansen.

C.M. Baum, and J. Bass-Haugen (Eds.), Occuational Therapy: Performance, participation, and well being (3 rd ed.). THorofare, NJ: Slack Incorporated.

Bramham, J., Young, S., (2007) ADHD in Adults; A Psychological Guide to Practice.

John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., West Sussex,England.

DuPaul, G., Weyandt,L., O’Dell, S.M., Varejao, M., (2009). College Students with

ADHD. Current status and future directions. Journal of Attention Disorders, 13(3),

234-250.

Dunn, W., Bennett, D, (2002) Patterns of sensory processing in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research,

22(1), 4-16.

Gutman, S.A., Szczepanski, M., (2005) Adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity

Disorder: Implications for Occupational Therapy Intervention. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 21(2), 13-38.

28

Himanshu P. Upadhyaya, Kelly Rose, Wei Wang, Kathleen O'Rourke, Brian Sullivan,

Deborah Deas, Kathleen T. Brady. (2005) Journal of Child and Adolescent

Psychopharmacology., 15(5): 799-809.

Johnson, M.E., Irving, R., (2008) Implications of Sensory Defensiveness in a College

Population. Sensory Integration Special Interest Quarterly / American Occupational

Therapy Association. 31(2), 1-3

Katz, L.J. (1998, March/April). Transitioning into college for the student with ADHD.

The ADHD Challenge, 12, 3-4.

Kinnealey, M. Oliver, B. Wilbarger, P. (1995) A phenomenological study of sensory defensiveness in adults. American Journal of Occupational Therapy,49(5), 444-51.

Lane, S. J., Miller, L. J., & Hanft, B. E. (2000). Toward a consensus in terminology in sensory integration theory and practice: Part 2: Sensory integration patterns of function and dysfunction. Sensory Integration

Special Interest Section Quarterly, 23, 1 –3.

Lewandowski, L.J., Lovett, B.J., Codding, R.S. & Gordon, M. (2008). Symptoms of

ADHD and academic concerns in college students with and without ADHD diagnoses. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12, 156-161.

Mangeot, S.D., Miller, L.J., McIntosh, D.N., McGrath-Clarke, J., Simon, J.,

Hagerman, R.J., Goldson, E. (2001) Sensory modulation dysfunction in children with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology,

43:399-406

Meaux, J.B., Green, A., Broussard., (2009) ADHD in the college student: a block in the road. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 16, 248-256

Miller,L.J., Anzalone,M.E., Lane,S.J., Cermak,S.A., Osten. E.T.(2007) Concept

Evolution in Sensory Integration: A Proposed Nosology for Diagnosis. American

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 135-140.

29

Norwalk, K., Norvilitis, J.M., & McLean, M.G., (2008). ADHD symptomatology and its relationship to factors associated with college adjustment. Journal of Attention

Disorders, 1-8

Oliver, M. The Politics of Disablement. Basingstoke, Macmillan (1990)

Parker, D., Benedict, K.B., (2002) Students with ADHD Assessment and

Intervention: Promoting Successful Transitions for College Assessment for Effective

Intervention, 27 (3)

Parker, D.,Boutelle, K. (2009) Executive Function Coaching for College Students with Learning Disabilities and ADHD: A New Approach for Fostering Self-

Determination. Learning Disabilities and Research and Practice, 24(4), 204-215

Reaser, A., Prevatt, F., Petscher, Y. & Proctor, B. (2007). The learning and study strategies of college students with ADHD. Psychology in the Schools, 44, 627-638.

Seidman, A. (ed.) College student retention: Formula for student success. Westport,

CT: ACE/Praeger (2005).

Shakespeare, T., Watson, N., The social model of disability: an outdated ideology?

Research in Social Science and Disability Volume 2, pp. 9-28 (2002).

Singer, J. Why Can’t You Be Normal for Once in Your Life in Marian Corker and

Sally French (eds.), Disability Discourse , Buckingham, England: Open University

Press, 1999, p. 64

Trinity College Dublin, http://www.tcd.ie/Communications/Facts/student-numbers.php

(Accessed May 11th 2010).

Thome, J., Reddy, D.P., (2009) The Current status of research into attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: proceedings of the 2 nd international congress on ADHD: from

30

childhood to adult disease. ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders, 1(2),

165-174.

Weyandt, L.L., DuPaul, G. (2008) ADHD in College Students: Developmental

Findings. Developmental Disabilities Research Review, 14, 311-319

Upadhyaya HP, Rose K, Wang W, O'Rourke K, Sullivan B, Deas D, Brady KT.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, medication treatment, and substance use patterns among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent

Psychopharmacology. 2005;15:799-809.

31

Appendix 1:

Diagnostic criteria for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

According to the DSM-IV-R , the following five criteria (A-E) must be met in order for a diagnosis of ADHD to be made:

A. Either (1) or (2):

(1) six (or more) of the following symptoms of inattention have persisted for at least six months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level.

Inattention a. often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in school work, work, or other activities b. often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities c. often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly d. often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (not due to oppositional behavior or failure to understand directions) e. often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities f. often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (such as schoolwork or homework) g. often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., toys, school assignments, pencils, books or tools) h. is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli i. is often forgetful in daily activities

(2) six (or more) of the following symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have persisted for at least six months to the degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level.

32

Hyperactivity a. often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat b. often leaves seat in classroom or in other situations in which remaining seated is expected c. often runs about or climbs excessively in situations in which it is inappropriate (in adolescents or adults, may be limited to subjective feeling of restlessness) d. often has difficulty playing or engaging in leisure activities quietly e. is often "on the go" or often acts as if "driven by a motor" f. often talks excessively

Impulsivity b. often blurts out answers before questions have been completed c. often has trouble awaiting turn d. often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games)

B. Some hyperactive-impulsive, or inattentive symptoms that caused impairment were present before age 7 years;

C. Some impairment from the symptoms is present in two or more settings

(e.g., at school [or work] and at home;

D. There must be clear evidence of clinically significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning;

E. The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of a

Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Schizophrenia, or other Psychotic

Disorder and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder

(e.g., Mood Disorder, Anxiety Disorder, Dissociative disorder, or a

Personality Disorder).

(DSM-IV APA 1994)

33

Appendix 2:

DSM V 314.0x

Diagnostic Criteria for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=383#

(Accessed June 2 nd 2010)

The disorder consists of a characteristic pattern of behavior and cognitive functioning that is present in different settings where it gives rise to social and educational or work performance difficulties. The manifestations of the disorder and the difficulties that they cause are subject to gradual change being typically more marked during times when the person is studying or working and lessening during vacation.

Superimposed on these short-term changes are trends that may signal some deterioration or improvement with many symptoms becoming less common in adolescence. Although irritable outbursts are common, abrupt changes in mood lasting for days or longer are not characteristic of ADHD and will usually be a manifestation of some other distinct disorder.

In children and young adolescents, the diagnosis should be based on information obtained from parents and teachers. When direct teacher reports cannot be obtained, weight should be given to information provided to parents by teachers that describe the child’s behavior and performance at school. Examination of the patient in the clinician’s office may or may not be informative. For older adolescents and adults, confirmatory observations by third parties should be obtained whenever possible.

A. Either (1) and/or (2).

1.

Inattention: Six (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted for at least 6 months to a degree that is inconsistent with developmental level and that impact directly on social and academic/occupational activities. Note: for older adolescents and adults (ages 17 and older), only 4 symptoms are required. The symptoms are not due to oppositional behavior, defiance, hostility, or a failure to understand tasks or instructions.

(a) Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or during other activities (for example, overlooks or misses details, work is inaccurate).

34

(b) Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (for example, has difficulty remaining focused during lectures, conversations, or reading lengthy writings).

(c) Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly (mind seems elsewhere, even in the absence of any obvious distraction).

(d) Frequently does not follow through on instructions (starts tasks but quickly loses focus and is easily sidetracked, fails to finish schoolwork, household chores, or tasks in the workplace).

(e) Often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities. (Has difficulty managing sequential tasks and keeping materials and belongings in order.

Work is messy and disorganized. Has poor time management and tends to fail to meet deadlines.)

(f) Characteristically avoids, seems to dislike, and is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (such as schoolwork or homework or, for older adolescents and adults, preparing reports, completing forms, or reviewing lengthy papers).

(g) Frequently loses objects necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., school assignments, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, or mobile telephones).

(h) Is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli. (for older adolescents and adults may include unrelated thoughts.).

(i) Is often forgetful in daily activities, chores, and running errands (for older adolescents and adults, returning calls, paying bills, and keeping appointments).

2.

Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted for at least 6 months to a degree that is inconsistent with developmental level and that impact directly on social and academic/occupational activities.

Note: for older adolescents and adults (ages 17 and older), only 4 symptoms are required. The symptoms are not due to oppositional behavior, defiance, hostility, or a failure to understand tasks or instructions.

(a) Often fidgets or taps hands or feet or squirms in seat.

35

(b) Is often restless during activities when others are seated (may leave his or her place in the classroom, office or other workplace, or in other situations that require remaining seated).

(c) Often runs about or climbs on furniture and moves excessively in inappropriate situations. In adolescents or adults, may be limited to feeling restless or confined.

(d) Is often excessively loud or noisy during play, leisure, or social activities.

(e) Is often

“on the go,”

actin g as if “driven by a motor.” Is uncomfortable being still for an extended time, as in restaurants, meetings, etc. Seen by others as being restless and difficult to keep up with.

(f) Often talks excessively .

(g) Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed. Older adolescents or adults may complete people’s sentences and “jump the gun” in conversations.

(h) Has difficulty waiting his or her turn or waiting in line.

(i) Often interrupts or intrudes on others (frequently butts into conversations, games, or activities; may start using other people’s things without asking or receiving permission, adolescents or adults may intrude into or take over what others are doing).

(j) Tends to act without thinking , such as starting tasks without adequate preparation or avoiding reading or listening to instructions. May speak out without considering consequences or make important decisions on the spur of the moment, such as impulsively buying items, suddenly quitting a job, or breaking up with a friend.

(k) Is often impatient , as shown by feeling restless when waiting for others and wanting to move faster than others, wanting people to get to the point, speeding while driving, and cutting into traffic to go faster than others.

(l) Is uncomfortable doing things slowly and systematically and often rushes through activities or tasks.

(m) Finds it difficult to resist temptations or opportunities , even if it means taking risks (A child may grab toys off a store shelf or play with dangerous

36

objects; adults may commit to a relationship after only a brief acquaintance or take a job or enter into a business arrangement without doing due diligence).

B.

Several noticeable inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present by age 12.

C.

The symptoms are apparent in two or more settings (e.g., at home, school or work, with friends or relatives, or in other activities).

D.

There must be clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with or reduce the quality of social, academic, or occupational functioning.

E.

The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (e.g., mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder).

Specify Based on Current Presentation

Combined Presentation: If both Criterion A1 (Inattention) and Criterion A2

(Hyperactivity-Impulsivity) are met for the past 6 months.

Predominately Inattentive Presentation: If Criterion A1 (Inattention) is met but

Criterion A2 (Hyperactivity-Impulsivity) is not met and 3 or more symptoms from

Criterion A2 have been present for the past 6 months.

Predominately Hyperactive/Impulsive Presentation: If Criterion A2 (Hyperactivity-

Impulsivity) is met and Criterion A1 (Inattention) is not met for the past 6 months.

Inattentive Presentation (Restrictive): If Criterion A1 (Inattention) is met but no more than 2 symptoms from Criterion A2 (Hyperactivity-Impulsivity) have been present for the past 6 months.

37

Appendix 3:

DARE Screening Criteria – Attention Deficit (Hyperactivity) Disorder www.accesscollege.ie

(Accessed May 11 th 2010).

Ac c e p t e d M e d i c a l

C o n s u l t a n t / S p e c ia l i s t

Students should ideally be diagnosed within a multi disciplinary team setting. Students can be diagnosed by an appropriately qualified psychiatrist/psychologist who is a member of their respective professional or regulatory body.

All applicants should complete the Evidence of

Disability Form 2010 .

E vi d e n c e o f D i s a b i l i t y

Ag e o f R e p o r t

Applicants who have an existing report completed by the accepted Medical

Consultant/Specialist may submit this report. The report must have been completed within the appropriate timeframe and must contain the same detail as the Evidence of Disability Form.

While there is no age limit on diagnostic evidence submitted it is advisable to submit a recent report.

O t h e r D i s a b il i t i e s

Where there are two or more co-existing disabilities, then evidence of each disability must be submitted for consideration under DARE.

Student’s personal statement should outline the impact of disability on their academic and educational experience to date.

P e r s o n a l S t a t e me n t a n d

Ac a d e m i c R e f e r e n c e

The Academic Reference provides background inf ormation on the student’s educational experience, stating the educational impact of the

38

D AR E E l i g i b i l i t y disability and describing the need for any supports and/or accommodations in third level.

The applicant is eligible for consideration once the appropriate professional has provided a diagnosis of Attention Deficit Disorder/Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder.

39