Download Shared Governance Final Report

advertisement

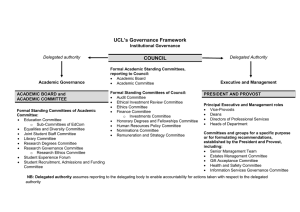

Report from the Shared Governance Research Task Force Submitted to Faculty Council, Interim Provost Linda Petrosino and President Thomas Rochon History On May 17, 2013, Faculty Council passed the following motion establishing the Shared Governance Research Task Force: Shared Governance Research Task Force Charge Charge: 1. To research, examine and recommend putting forth for discussion a variety of Shared Governance structures suitable for adoption and implementation at Ithaca College; 2. To articulate all of the potential pros and cons of each structure recommended. Membership: 1. Three faculty members chosen by Faculty Council; 2. Three administration members chosen by the President and Provost or by such means as they derive. Other: 1. The Task Force reports directly to Faculty Council and the President and Provost; 2. The Task Force should endeavor to complete its study by January 1, 2014, but may extend that date as needed. Task Force Membership and Process The college administration responded positively and the Shared Governance Research Task Force was convened with three administrators (Karl Paulnack, Dean of the School of Music, Carol Henderson, Associate Provost for Accreditation, Assessment and Curriculum, and Linda Petrosino, Dean of the School of Health Sciences and Human Performance) and three faculty members elected by Faculty Council (Vivian Bruce Conger, Associate Professor of History, Howard Erlich, Associate Professor of Communication Studies, and Jorge Grossman, Associate Professor of Music Composition). After their first meeting, Peter Rothbart, Chair of Faculty Council and Professor of Electroacoustic Music, also joined the Task Force, to serve as facilitator. Linda Petrosino subsequently left the group upon her appointment as Interim Provost; Michael Richardson, Associate Dean for Faculty and Special Initiatives from the School of Humanities and Sciences was appointed to fill the vacancy. 1 The Task Force engaged in considerable research and discussion as well as outreach to colleagues at other institutions in developing this document. They held a onehour open meeting to solicit faculty input regarding current issues of governance at the college. The college supported a two-day retreat at which members discussed the various college governance options available and began developing a rough draft of this document, by breaking into groups of two, each group assuming responsibility for developing one governance model. A schedule was established, during which time the three Task Force teams further developed their assigned governance model, then submitted it for comments from the complete Task Force. Each team then considered those comments in revising their portion of the final document, which was then edited for form and cohesiveness before being finally approved by the entire Task Force. It should be noted that Peter Rothbart, while serving as facilitator, also took an active role in developing the document, since one Task Force member was not available for the retreat. The Task Force completed its work by September 1, 2014 and hereby submits it to Faculty Council and the President and Provost of Ithaca College, as per its charge and is hereby dismissed from service. About This Document The intent behind this document and the motion that brought the Shared Governance Research Task Force into existence was to examine and/or develop a variety of college governance models that might be applicable to Ithaca College. The hope was to further establish the idea of shared governance, and to allow the college and its constituencies to engage more efficiently and effectively through the governance process. The Task Force is not endorsing or encouraging one model of governance over another. The Task Force acknowledges that additional models of governance exist at other institutions, but after long and careful research and discussion, the Task Force feels that these three models hold the most potential for Ithaca College. The Task Force included a list of pros and cons for each of the governance systems described. It should be understood that these are subjective, anecdotal lists, not intended to be all-inclusive, but rather to help initiate further discussion. Further discussion regarding these models is certainly warranted. The Task Force encourages all constituencies at the college to engage in cooperative dialog regarding the relevance of this document, and whether it is feasible, necessary and desirable to implement one of the proposed models, or some variation of it. The Task Force was not charged with charting the course of the discussion once their document has been delivered to the Faculty Council, President and Provost. Nonetheless, a discussion was held in which it was suggested that a centralized source of information and forum for commentary be established, along with series of open meetings be held to discuss the document. It was suggested that open meetings might include not just faculty and administrators but perhaps staff and students as well. 2 It is worth noting that the Task Force identified communication as a key component of successful governance. In order to be effective, any model of governance we use, including our current one, must have better communication than has been the norm in the past. Analysis by the Task Force clearly showed that communication among and between all groups on our campus has not been as effective as is should be. Certainly one of the most important things to come out of this Task Force is the recognition that any form of governance will be ineffective if communication among all constituencies is not properly cultivated. Respectfully submitted, Vivian Bruce Conger Howard Erlich Jorge Grossman Carol Henderson Karl Paulnack Michael Richardson Peter Rothbart 3 Models Proposed for Consideration The Task Force proposes three governance models for consideration. The first, Traditional Model Revisited, is essentially a modified version of the system we currently use, with changes and enhancements added to address issues identified by the Task Force during their research. The Sustainable System Governance (SSG) model acknowledges the need for systemic structure and stability in the College’s governance system, balanced with the need for fluidity, change, responsiveness, inclusiveness and interdependence. The Collaboration and Consultation model is based on a structure in use at Santa Clara University; it relies on a central committee to guide the governance process, and emphasizes the role of stakeholder groups in timely decision-making. For each of these three models, a brief description is provided, along with a list of pros and cons. Also included is a set of three scenarios to illustrate how each model might operate in practice. The first scenario is the creation of a new course with Integrative Core Curriculum (ICC) themes and perspectives designations. The second scenario is a change in college employees’ percentage of contribution toward the cost of health benefits. The third looks at how the College might make decisions related to the design and construction of a new building. Model One: Traditional Model Revisited This proposed system modifies and builds upon our current system of governance, recognizing that many elements of the idea of Shared Governance already exist in our current bylaws and documentation. However, in many cases, we are simply not following our own published procedures and rules. In other cases, this model fills gaps in our current system. It is clear that communication under our current system is often ineffective. Fundamental to the proposed model is the improvement, codification and enforcement of lines of communication among all stakeholders. This model acknowledges that while faculty members are certainly cognizant of their service responsibilities to the college, their primary focus is on teaching and scholarship. The model attempts to encourage faculty representation on relevant committees but in a strategic way, relying on open communication and ready access to information coupled with an easy, efficient method of response and input into issues that affect the faculty’s primary focus. The current governance structure adheres closely to the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities, which affirms the need for joint efforts among various constituencies -- faculty, staff, administrators, students -- while acknowledging specific areas of primary responsibility associated with each group. While the faculty has primary responsibility for areas such as curriculum, subject matter and methods of instruction, research, faculty status, and aspects of academic student life related to the educational process, the President has 4 ultimate managerial responsibility and authority, and the Board of Trustees holds final institutional authority. Implicit in this model is the fact that committee recommendations, particularly as they pertain to academic policy, are subject to the ultimate approval of the President and the Board of Trustees. In principle, within each constituent group there exist lines of authority, responsibility, and communication. The participation of these groups in the decision making process, in the form of public forums, committee participation, and/or opportunities for feedback, allows a broad range of perspectives to be considered. A commitment to sharing information, in the form of agendas, minutes, recommendations, and reports, allows for transparency in the decision making process. However, current practices do not always reflect the model as it is currently codified, in the Ithaca College Policy Manual and in the bylaws of the college’s councils and committees. We are experiencing problems with the implementation of the model, rather than with the model itself. This proposal builds upon the existing model, reinforces key concepts of that model, addresses insufficiencies and omissions, and provides for a more interactive relationship among all concerned groups. Key Elements: 1. Governing councils: Faculty Council, Staff Council, and the Student Government Association represent key constituencies. Faculty, staff, students, and administrators all have representative bodies to which they may bring concerns. For administrators, the Administrative Assembly could function as this body. 2. Committee definitions, mandates, and review: Governing councils and appropriate administration officials may at their discretion call into existence a task force or ad hoc committee to address specific issues. Governing councils and administration officials are expected to reevaluate all of their standing and ad hoc committees and task forces on a regular basis with respect to purpose, structure, membership, and leadership. Ad hoc committees and task forces should automatically sunset once their initial purpose has been met, unless otherwise decided by the council or official that created them. All governing councils and administrative officials should clearly communicate the charge, make up, and designation (monitoring, policy-making, or advisory) of their respective committees. By definition, advisory committees are those which serve primarily as information resources for policy makers. Policy making committees are those committees charged with reviewing existing policy and making recommendations regarding the revision of existing policy and the drafting of new policy. Recommendations made by these committees would generally be accepted and implemented by the institution, except for cases in which they could not be approved due to overriding budgetary, policy or regulatory concerns as indicated by the President, Provost, General Counsel, or their offices, Faculty Council, Staff Council, or the Board of Trustees. Monitoring committees are neither advisory nor policy making committees. They are charged with making sure that a policy 5 or procedure is being effectively carried out, and that other groups under their jurisdiction are successful in their efforts. In most cases, these committees will report their findings to a policy-making committee, supervising administrative official and/or council. 3. Committees and their structure: It is important to carefully delineate the roles and responsibilities of each committee, sub-committee, ad hoc committee and task force. Each of these groups’ charge must indicate whether it is policy making, , advisory or monitoring. In addition, when establishing or reauthorizing the group, the committee’s initiating administrative official or council must determine the status and charge of the group. Most, if not all, academic committees have participating representatives from both faculty and administration, allowing for collaborative work on strategic governance and management issues. Not all committees require representative membership structures, meaning a balance of members from each school; membership on some committees should instead be expertise or competency based. “Expertise or competency based” is taken to mean that the committee members have special, specific knowledge, skills or interests relevant to the committee. Other committees, such as those responsible for making policy or curriculum recommendations which will have a significant impact across the institution (such as the Academic Policies Committee, or the Committee on College-Wide Requirements) should be representative, taken to mean that a balance between the various schools and administrative structures is established. In either case, the committee must reach out to all relevant and interested parties for information, data and constructive opinions and ideas. Any further pursuit of this model should include guidelines for establishing the nature and character of committee charges, communication procedures, and committee makeup. 4. Cross-constituency openness: Any member of the college community may bring an issue either to an appropriate standing committee or to their own representative council. For issues that defy clear assignment, a standing committee or council could refer the issue to the relevant faculty, staff, administrative or student council. Councils will have the ability to examine any issue presented to them by other committees or by individuals. 5. Access and communication: Although open access and communication regarding governing body and committee actions (minutes, agendas, decisions, etc.) is mandated by the current policy manual, implementation is uneven, sporadic, and decentralized. The revised IC model would thus include a renewed commitment to communication and openness, enhanced by an updated web presence with access to information and committee member contact information through a central portal to be maintained by the college as a whole and accessible to all constituencies. Governing councils would hold town halls and open meetings on issues of major concern throughout the decision-making and implementation processes. 6 6. Accountability: Governing councils and appropriate administration officials are responsible for ensuring that their committees maintain proper and timely communication with the larger Ithaca College community. Committees provide the appropriate governing council or lead administrator with regular updates and additionally update their web presence at least once each month during the academic year. Pros: 1. Clear articulation of roles and responsibilities 2. Processes are defined 3. Enduring model that has met with success in a variety of institutions and situations over time. 4. Does not appreciably add to existing faculty work/service load. 5. Builds upon widely accepted AAUP principles. 6. While much of the structure may already be in place, this model refines and reinforces elements that have proven successful at IC, while revising and remaking elements that have been less successful. Cons: 1. Could encourage complacency within constituencies. 2. Potential for committees to resist input from stakeholders not affiliated with the committees’ governing councils. 3. Model as codified is often better than the model as practiced. Scenarios: Scenario One: Creating a new course with theme and perspective designations. The faculty member submits a course proposal to his/her respective department and school committees. Once locally approved, that proposal is submitted simultaneously to the Academic Policies Committee and the CCR. Upon approval by APC, CCR and the Provost, the course becomes part of the catalog. Scenario Two: Health benefits cost increase for employees Any faculty or staff member may address their respective Council regarding salary or compensation issues. The Council may choose to study the issue in more depth, or refer it to their respective budget committee for consideration and development. Any discussion would be posted on the central website with the opportunity for comments from the community. Should the committee decide that the issue warrants further comment, an open meeting could be called. After the meeting, the committee would respond to the petition, shape a counter-proposal, if warranted, and submit it to the respective council for a vote. The council would then engage with the petitioner to convey the results of the vote. Scenario Three: New building on campus. 7 Any community member may raise the issue of a new facility with the relevant Council and/or the relevant all-campus facilities and planning committee. That committee would solicit input from a variety of sources, including online sources, open meetings and experts regarding the relevance, timeliness and viability of the issue. All materials would be posted online. Relevant Councils would be responsible to make sure that stakeholder input was represented properly and would have the power to constitute adhoc committees to render input (while providing public output) as the proposal/project progresses. Model Two: Sustainable System Governance The Sustainable System Governance (SSG) model relates to sustainability in multiple ways. It is characterized by a balance between stability and change. It includes a stable structure with a small number of standing committees, and also a process for creating and supporting fluid, flexible working groups. It is adaptable to multiple styles of leadership and participation. Although it can be “flavored” by personalities, it is not locked into a specific personality style or leadership approach. Individual people can come and go, enter and leave the system, without creating imbalance or disharmony, more readily than in many other governance structures. The SSG model encourages and supports integration and interdependence among various areas of the institution, across traditional boundaries. It is informed by systems theory, and intended to function largely as a self-governing model. It increases the opportunity for anyone within the organization to take a leadership role on issues and items that concern them, and calls on each participating individual to engage around issues that matter. The success of SSG depends upon a fairly high level of distributed engagement on the part of multiple areas and constituencies. This model is characterized by open communication and participation in a clearly-understood and well-facilitated process. SSG is made up of four key elements: 1. An integrated Bulletin Board System (BBS) for easy internal sharing and tracking of governance work and governance structures. An example of such a system is the software product FirstClass, which is used by many colleges and universities for this purpose. A BBS is an online system that allows any member of the organization to access governance and decision-making information, track related processes, and either participate actively in the related online conversations or stay informed about what others are doing. 2. Open Space Technology, as a way to hold a periodic, ongoing series of facilitated open meetings, leading to concrete action plans. Open Space Technology (OST) [ see www.openspaceworld.org/ for additional information] is a structured, organized method of bringing together large groups in a way that surfaces issues and concerns, allows expression of individual viewpoints, and brings together smaller teams for discussion and development of action plans. Each OST session 8 results in a series of action plans and individual/group commitments, which are brought back to the full group near the end of the session. This technique allows open meetings to be more practical and productive, and organizes the results in ways that are easy to record, store, access and understand. Open Space sessions with no specific theme would be made available on a regular basis, perhaps once or twice each year. Open Space sessions could also be held on specific topics, or by/for particular constituency groups, such as faculty. 3. “Zero-based” governance structures, including a minimal basic set of standing committees, serving as the backbone of the system, and as-needed committees that expire within a standard period unless renewed. In this model, the minimal basic set is proposed to include six college-wide standing committees: one each for the areas of curriculum, budget, facilities, tenure & promotion, strategic planning, and assessment/institutional effectiveness. 4. Cross-Divisional Functional Teams (CDFT): issues not covered by a specific group within the standing committees would be addressed by the use of crossdivisional functional teams. These groups would come into existence, bring their task or issue to completion, and then go out of existence. This approach ensures that the overall system stays simple over time, rather than becoming more complex by adding new committees as new issues and tasks emerge. Team members are selected by their function within the institution, rather than by constituency membership or academic school; faculty serving on such a team would be chosen by their connection with its main topic. An example of a CDFT at Ithaca College would be the NCUR coordination team. Charged with planning and operating the 2011 National Conference on Undergraduate Research, this team was made up of administrators from key areas (such as Auxiliary Services, or Public Safety and Emergency Management) as well as faculty members with a history of engagement and interest in undergraduate research. It also included two students, who were taking an IC course in event management. 9 •Bulletin Board System •Cross Division Functional Teams •Open Space Technology BBS OST CDFT ZBG •"Zero Based" Governance 5. This model would be managed in its operational aspects by administrators, with each vice president of the college responsible for sustaining SSG in their area of responsibility, including the operation of Cross-Divisional Functional Teams. This aspect of the system would be counterbalanced by a strong Faculty Council, which would serve a monitoring role regarding system performance and integrity, and could actively engage the process whenever key issues and important topics might be overlooked, and/or need to have more prominence and attention within the system. With the Bulletin Board System available to allow tracking of process, progress and results for each committee and team, faculty would be able to access this information, and could bring any related questions or concerns either directly to the committee/team members, or to the Faculty Council. The Faculty Council could then communicate with either the committee/team, or with the appropriate vice president, to address those questions or concerns. A similar role could be played by the Staff Council and the Student Government Association. Vice presidents working on the creation of a CDFT would gather input from the Faculty Council, Staff Council and/or Student Government Association, as well as from other administrators, regarding the charge and membership of the team, as appropriate for the topic or issue under review. Pros: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Allows ideas to originate from anyone and anywhere within the organization. Has a strong key role for Faculty Council. Can reduce the overall workload of governance. Characterized by open communication and transparency. Can support the growth of trust and help to sustain trust over time. 10 6. Allows integrators among different areas of the college to flourish within the system. 7. Allows distributed leadership, letting any participant be part of the leadership aspect of issues that matter to them, whether as a committee/team member, a participant in open sessions, or a member of their constituency group. 8. Reduces silos and isolation in decision making. 9. Mitigates against “us vs. them” inter-group dynamics. 10. Promotes engagement in governance, at a relatively low individual cost/investment. 11. Open to participation by all types and levels of faculty members. Cons: 1. System may get bogged down by a few individuals who continue to reintroduce the same issues. 2. Model is unusual, appears to be complex, and may be difficult to learn. 3. Participants in the prior governance system may perceive a reduction of their authority. 4. Loss of influence for long-time participants in current system. 5. Although elements of this model exist and are used effectively, the entire system has not yet been implemented elsewhere. 6. Distributes leadership, in a way that calls on many participants for leadership at multiple levels. 7. Requires widespread engagement from multiple individuals and constituencies, as committee/team members, participants in open sessions, and active participants through their constituency groups. Scenarios: Scenario One: Creating a new course with themes and perspectives designations. A course proposal would be developed by interested faculty member(s), brought through the departmental and school review processes as appropriate to the subject area, and referred to a college-wide curriculum committee for final review and approval. At every stage in the process, the proposal would be widely available and readily accessible through the Bulletin Board System, so that any interested party could track its progress and monitor any changes made over time. (Note that this process does not differ from the current approval process, as curriculum is one of the six standing committees proposed. See #3 above, “Zero-Based” governance structures.) Scenario Two: Health benefits cost increase for employees The process could begin with an Open Space session focused on this topic area. The results of that session would be made available to all college employees through the 11 Bulletin Board System, and the vice presidents primarily responsible for the related areas (finance and human resources) would put together a Cross-Divisional Functional Team to study the topic. The team would prepare a report of information, recommendations and options to consider; a record of their work, and a copy of their report would be available through the BBS. The report would be received by the appropriate vice-presidents, and then go to the Finance standing committee for review and approval. The Faculty Council and Staff Council would have access to related information through the BBS throughout the process, and members of these groups should also be participants in the functional team. Also, since this particular issue falls within the responsibilities of the President and Board of Trustees, they would also need to approve any plan before it could be put into action. Scenario Three: New building on campus. The need for a new structure would most likely arise in one of the twice-yearly general Open Space sessions. A special topic Open Space session could follow, to gather broad input into the deliberation process. A Cross-Divisional Functional Team would be called together by the vice president responsible for facilities to study the topic, gather input, and develop recommendations. The work of this team would come back to the vice president, and would be provided to the Facilities standing committee, as well as to the Budget committee. Since this topic crosses over both of those areas, the two standing committees would need to work together in a joint process of review and approval. The process and its results would be continuously accessible to college employees through the BBS. Final approval by the President and Board of Trustees would also be required for this type of decision. Model Three: Collaboration and Communication This model draws from an article by André Delbecq, et. al., “University Governance: Lessons from an Innovative Design for Collaboration,” Journal of Management Inquiry, 22/4 (2013). It is a model used with success at Santa Clara University. It entails a College Coordinating Committee (CCC), six College Policy Committees (CPCs), and implementation procedures. At the first stage, any stakeholder group or any member of the college community submits an issue of concern (that is, an issue that needs to be addressed by a governing body) to the College Coordinating Committee. At the second stage, the College Coordinating Committee (made up of five members: an elected faculty chair, an elected faculty member at large, the provost, president of faculty council, and president of staff council) appoints faculty, staff and students to serve on College Policy Committees on the basis of competency. It is the responsibility of the CCC to develop and maintain information on faculty and staff regarding their expressions of experience, expertise, and interest in topics considered by the various CPCs. This information should be shared with CPCs as needed. The CCC is responsible for triaging—that is, sorting and prioritizing requests on the basis of what is most urgent and the most efficient and effective response—each issue submitted by any 12 of the College’s stakeholder groups, and assigning it to the appropriate College Policy Committee. It is also the responsibility of the CCC to guarantee appropriate consultation and efficient deliberations of each CPC. Standing College Policy Committees include Academics, Faculty Affairs, Staff Affairs, Student Affairs, Strategic Planning, and Budget. Additional task forces can be created as needed, especially for issues that bridge more than one CPC. At the third stage, the appropriate policy committee approaches each issue submitted to it in three steps: definition of the problem; determining possible solutions; and recommending the solution. Recommendations are generally adopted as proposed, except when the President or the Board of Trustees can present compelling reasons for not doing so. Transparency (that is, effective communication and collaboration) at each stage is crucial. Effective communication entails publishing agendas, briefing key decision makers, soliciting input from the College community, and systematically reporting actions. At the fourth stage, administrators or appropriate bodies are responsible for responding within 45 days and providing an action plan. In rare cases of continued dispute, the case is referred back to the College Coordinating Committee in consultation with the President for mediation. Faculty Staff GCC Students The Governance Coordinating Committee (GCC) gathers input from multiple constituencies, and refers each issue to the appropriate group or office for review and resolution. 13 Pros: 1. Gives stakeholders a clear voice in the collaborative decision-making process. 2. Oversight by the CCC throughout the process should ensure that no key stakeholder group oversteps its bounds. 3. Provides a clear and logical system in which every issue receives full consideration. 4. Because of the clear structure, every member of the community knows where to go to resolve concerns. 5. The system does not allow concerns to be discussed and then simply filed away; CPCs are given the power to provide recommendations that are generally adopted as proposed. 6. Process requires that a clear implementation plan be articulated in a timely fashion. 7. Committee structure is more efficient and less cumbersome. Cons: 1. Stakeholders may not be fully committed to collaborative governance, especially newly appointed faculty, staff and administrators. 2. Stakeholders may resist offering their expertise. 3. Stakeholders may not feel invested in the process; they may drift into complacency. 4. The CCC does not have enough information about competencies without stakeholders volunteering that information; there has to be a clear system to identify potential committee members. 5. If every issue is considered by the CCC, then the CCC could become overwhelmed or the process could lose its effectiveness. 6. Unclear how this model affects Faculty Council, and also how complex decision making would occur between Faculty Council and the various CPCs. Scenarios: Scenario One: Creating a new course with theme and perspective designations A school, department or faculty member submits a proposal for a new theme course. The CCC receives the petition, and reviews it. The CCC then passes the issue on to the appropriate CPC, which in this particular case would be the Academics CPC. The CPC deliberates on the proposal and approves it, rejects it, or recommends amendments. During the review process, the CPC publishes meeting agendas and minutes, briefs key decision makers, solicits input from the college community, and systematically reports actions. Scenario Two: Health benefits cost increase for employees One stakeholder group submits a petition to raise employees’ contribution to health coverage. Once the petition is submitted to the College Coordinating Committee, the CCC reviews the issue in order of priority. The CCC then decides which College Policy Committee to assign the issue to or whether special task force needs to be created. In this case, because of the nature of the petition, the CCC could opt for one of two methods to address the issue: 14 1) Create a task force that would bridge the faculty affairs, staff affairs and budget CPCs. Members of the task force would be selected from the three CPCs in question on the basis of competence and representation. Once the task force is formed, it would deliberate on the issue and publish agendas, brief key decision makers, solicit input from the College community, and systematically report actions. The task force would then submit its final recommendation to the appropriate governing bodies for approval. 2) The CCC would assign the issue to the Budget CPC. The CPC would then deliberate on the issue and work closely with Faculty Council, Staff Council and administrators in addition to soliciting input from the college community before submitting its final recommendation. Scenario Three: New building on campus The community learns of new plans for an impending “Creativity Center.” A concerned member of the faculty attends the information sessions and walks away with real concerns. That person brings the issue to the CCC for consideration. The CCC would assign the issue to the Strategic Planning CPC for deliberation. That CPC would work closely with the Budget CPC, the Academics CPC, as well as Faculty Council and administrators—each of whom may consult designated experts at their discretion. Given the nature of the proposed use of the new building, it would also be appropriate to have the Strategic Planning CPC solicit input from the Student Affairs CPC. Alternatively and ideally, given the nature of the concern and the CPCs involved, the CCC would create a separate task force bridging the various concerned communities to resolve the issue— again consulting designated experts at their discretion. Either the Strategic Planning CPC (and the various CPCs it consults) or the newly created task force would diligently solicit input from the college community, especially the academic community, publish meeting agendas, keep in touch with key decision makers, and make public their discussions and solicit feedback before submitting a final recommendation. 15