Savage_Stevens_Dissertation.doc (578Kb)

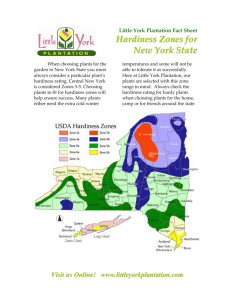

advertisement