Giorgetti et al(1997).doc

advertisement

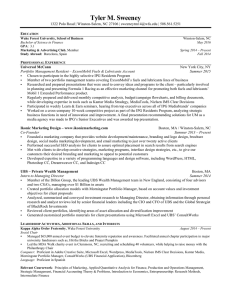

1 Abstract Interleaved phyllosilicate grains (IPG) of various compositions are widespread in low-grade Verrucano metasediments of the northern Apennines (Italy). They are ellipsoidal or barrel-shaped, up to 300400µm long and they are often kinked and folded; phyllosilicate packets occur as continuous lamellae or as wedge-shaped layers terminating inside the grain. Using electron microscopy techniques (SEM, TEM) six types of IPG have been distinguished on the basis of their mineralogical composition: (1) Chl+Ms±Kln; (2) Chl+Ms+Pg±Kln; (3) Ms+Prl±Pg; (4) Ms+Prl+Su; (5) Ms+Prl+Chl+Su; (6) Su+Ms. Types (1) and (2) are mainly composed of chlorite, with Ms and Pg as minor phases; Kln grows on Ms in highly weathered samples. Types (3), (4), (5), and (6) are composed of muscovite, with intergrown Prl, Chl, Su and new-formed muscovite. IPG show all kinds of contacts: from coherent grain boundaries with parallel basal planes and along-layer transitions to low- and high-angle grain boundaries. IPG formed on pristine minerals such as chlorite and muscovite. The transformations took place during the prograde and retrograde metamorphic path of the rocks: they were facilitated by deformation and they occurred in equilibrium with a fluid phase, which allowed cation diffusion. Prograde reactions (Chl=Ms (or Pg); Ms=Prl; Ms=Chl) involve dehydration and sometimes a decrease in volume, whereas retrograde reactions (Ms=Kln; Ms=Su) involve hydration and an increase in volume. These transformations do not simply occur through an interchange of cations, but often involve deep structural changes: transitions from one phyllosilicate to another 2 generally proceed through dissolution-recrystallization reactions. In conclusion, Verrucano IPG represent microstructural sites which have not completely equilibrated with the whole rock and whose mineral assemblage depends on the original composition of the microstructural sites. 3 Introduction Composite grains of chlorite and muscovite have been frequently recognized in sedimentary and low-grade metamorphic rocks; they are commonly called stacks, intergrowths, or aggregates. Since Sorby (1853) first described them, these grains have been observed in pelitic and psammitic rocks of different age (Craig et al., 1982; van der Pluijm and Kaars-Sijpesteijn, 1984 and bibliography therein), and various hypotheses have been proposed for their origin: 1) stacks are detrital grains, i.e. clasts which may or may not be modified during weathering and transport (primary origin) (Beutner; 1978); 2) stacks originate from the mimetic growth of chlorite (with or without new-grown muscovite) on a detrital nucleus during diagenetic to metamorphic stages (primary-secondary origin) (Craig et al., 1982; Woodland, 1982; 1985; Dimberline, 1986; White et al.,1985; Milodowski and Zalasiewicz,1991; Li et al., 1994); 3) the aggregates are strain-controlled porphyroblasts formed entirely during metamorphism (secondary origin) (Weber, 1981). This diversity of opinions probably reflects the actual variability in the origin of the aggregates. This study re-examines the fine-scale interleaved phyllosilicate grains (IPG from Franceschelli et al., 1991) of Verrucano rocks (northern Apennines) which constitute a quartz-arenite facies referred to the beginning of the Triassic rift process (Franceschelli et al., 1986 and bibliography therein). This group of formations experienced low-grade metamorphism (Franceschelli et al., 1986; Giorgetti, 1995) during the Apennine orogeny (Carmignani and Kligfield, 1990). Franceschelli et al. (1989; 1991) suggest that IPG 4 originated during deformation and metamorphism and formed on a detrital precursor. The envisaged mechanism supports the idea that IPG result from an equilibrium process among detrital muscovite, the matrix mineral assemblage and an internally buffered fluid phase. The proposed model for IPG formation on detrital muscovite can also be extended to detrital chlorite. Our purpose is to clarify the origin of the Verrucano IPG and their evolution during metamorphism using SEM-EDS and TEM. These methods allow detailed textural and chemical analyses. Specimen description and analytical techniques Samples examined for this study belong to the pyrophyllite+quartz zone (Franceschelli et al., 1986) and were collected from the Verrucano formations of the Monticiano-Roccastrada Unit which crops out along the mid-Tuscan ridge (Fig.1). The metapelites and quartzites consist of different modal proportions of detrital minerals and new-formed, metamorphic minerals (tab.1). Detrital minerals include quartz, muscovite, chlorite, minor feldspars and rare carbonates. Syn- to post-tectonic metamorphic minerals (mainly phyllosilicates and chloritoid) crystallize in different microstructural sites: phyllosilicates such as Ms, Chl, Prl, Su (sudoite), Kln (mineral symbols from Kretz, 1983) constitute the rock matrix and grow as fine-grained (<10 µm) crystals underlying the main schistosity, or replace detrital muscovite or chlorite, forming finely intergrown aggregates (IPG; Franceschelli et al., 1991). IPG are ellipsoidal or barrel-shaped, up to 300-400 µm in length. They 5 often maintain characteristics (such as microfolds, kinks, and pressure-solution effects at their borders) which suggest a detrital origin; furthermore, IPG are more abundant in coarse-grained samples (quartzites) than in fine-grained ones (metapelites). Polished thin sections were prepared for optical observations, SEM study using back-scattered electron (BSE) imaging and X-ray energy dispersive (EDS) analyses. Analyses were performed with an EDAX 9100/70 attached to a Philips 515 scanning electron microscope. The operating conditions were: 15 kV, 20 µA emission current, and a 0.2 µm beam spot size. Natural minerals were used as standards. In particular, several analyses were performed on an homogeneous muscovite crystal during the entire working period of the instrument. IPG for TEM observations were selected from polished sections using a petrographic microscope; the sections were glued onto Cu grids with a single central hole of 200-400 µm in diameter and thinned by argon ion mill (Gatan Dual Ion Milling 600 at Granada University). Two ion-milling conditions were used: 1) 6 kV, 1A, and 15° incident angle while perforating; 2) 6 kV, low-angle (12°) and low current (0.4A) final milling for ~4 hrs to clean the sample surface. Samples were analysed with two transmission electron microscopes: a Philips CM20, operating at 200 kV, with a LaB 6 filament, and a point to point resolution of 2.7 Å (Granada University), and a Philips EM 400T, operating at 120 kV, with a W filament, and a point to point resolution of ~4 Å (Siena University). 6 Diffraction patterns were obtained from selected areas (SAED); high-resolution images (HRTEM) were obtained following the procedures suggested by Buseck et al. (1988) and Buseck (1992). Both microscopes were equipped with a X-ray energy dispersive (EDS) EDAX DX4 which allowed semi-quantitative analyses of areas with a minimum size of 200 Å. Optical, SEM, and TEM results IPG (up to 300-400 µm in length) are always coarser than the matrix phyllosilicates, detrital quartz and feldspars. Most IPG are randomly oriented with respect to the bedding and the main schistosity and are sometimes strongly deformed. IPG are composed of different phyllosilicate packets from one to tens of microns thick; although the different phyllosilicates can sometimes be identified optically, they are more easily identified in BSE images. Most packets are intergrown parallel or subparallel to (001); some have a lenticular shape or grow as wedges, which terminate inside the stacks, forming semi-coherent boundaries with the neighboring phyllosilicates. New minerals in the stacks grow preferentially at grain boundaries, in extensional directions and along microfold hinges. The IPG are often weathered; they are coated by reddish hydroxides and Ti-Fe oxides grow along stack borders or between the phyllosilicate lamellae (Fig. 2). SEM-EDS analyses allowed the identification of 6 types of IPG with different phyllosilicate assemblages (tab.1). 7 Types (1) and (2) are composed of chlorite packets, which are optically continuous and separated by mica lamellae; types (3), (4), (5), and (6) show complex textures, in which continuous muscovite packets are intersected and split by other phyllosilicates with variable orientations. Type (1) and type (2) IPG Type 1 stacks (M62) belong to highly weathered quartzites containing limonitic haloes along veins and fractures and euhedral crystals of siderite, which are almost totally replaced by calcite+dolomite+hematite. The IPG are composed of weathered chlorite with parallel or subparallel intergrown packets of muscovite and lamellae or wedges of kaolinite; hematite can grow at the IPG borders. Type 2 IPG (M669) are made up of chlorite (60 to 70%), muscovite, and minor paragonite. Micas preferentially grow at the stack borders or in packets with (001) parallel or subparallel to the chlorite basal plane. Type 1 and 2 IPG are always embedded in a matrix comprising the same phyllosilicate assemblage (tab.1). Both IPG types show similar characteristics at the TEM scale, and they are summarized in table 1. Chl is the most abundant phase and occurs in packets several hundred Å thick (Fig.3a). Electron diffraction patterns show a onelayer polytype with sharp 00l reflections; rows with k≠3n sometimes have weak satellites indicating a 56Å spacing. A 4-layer polytype may therefore be present together with the dominant one-layer polytype (Fig.3b). Lattice fringe images show packets undeformed and defect-free 14 Å layers (Fig.3a). with 8 Muscovite occurs as a two-layer polytype either as isolated layers, interstratified with chlorite (Fig.3a), or as packets of variable thickness (Fig.4a). Muscovite in M62 IPG occurs as defect-free packets, whereas in M669 IPG lattice fringe images show packets with a typical "mottled structure" (Fig.5a), and defects such as layer splitting or termination can be observed. The textural relationship between chlorite and mica is analogous in the two types of IPG. Chl and mica are generally coherently intergrown with parallel (001) planes. A zone of disordered, interstratified chlorite and mica packets is shown in figure 4a; rarely, low- or high-angle grain boundaries can occur. The lateral transformation from chlorite layers to muscovite (or paragonite) layers is evident in figure 3a. AEM analyses of these mixed-layer packets fall on line between the two end-member mica and chlorite (Fig.4b). The presence of smectite layers, which would result in a higher Si content (as described by Nieto et al., 1994), can therefore be ruled out. Lenses ~50 Å thick without resolved basal planes are present within the muscovite packets: they are probably paragonite, as electron diffraction patterns display split pairs of 00l reflections with 10.0 Å and 9.6 Å lattice spacing corresponding to Ms and Pg (Fig. 5b). In addition, AEM analyses indicate the presence of muscovite and paragonite. Paragonite can also occur in muscovite-free packets or with subordinate potassium mica. Lattice fringe images are difficult to obtain because paragonite is easily damaged by the electron beam. Muscovite and paragonite are parallel (Fig.5b) intergrown or form low-angle grain boundaries. Neither compositionally intermediate 9 sodium potassium mica nor basal reflections with an intermediate periodicity are recorded. These features suggest the presence of two single phases rather than an intermediate phase, as described by Jiang and Peacor (1993). In M62 IPG, kaolinite is present as a one-layer polytype and the presence of dickite or nacrite (two-layer polytypes) can be ruled out. SAED patterns show different degrees of stacking order: reflections may be sharp or weakly streaked along c (Fig. 6a). Kaolinite occur in packets of 7 Å-layers intercalated with muscovite packets (Fig.6b). Muscovite-kaolinite have either parallel basal planes or slightly different orientation (Fig. 6a). The lateral transition from 10 Å-Ms layers to 7 Å-Kln layers occurs without the formation of an intermediate phase (Fig.6c). Furthermore, relics of 10 Å-layers can be observed inside kaolinite packets, causing deformation contrast of 7 Å-layers (Fig.6b). Type (3), type (4), type (5) , and type (6) IPG Type 3 IPG (M7) belong to quartzites with a muscovite, pyrophyllite, ±sudoite, and paragonite (recognized only at the TEM scale) matrix. The IPG generally contain more than 60% muscovite; pyrophyllite grows in packets or wedges inside the Ms crystal whereas paragonite is present in small (<10 µm) lenticular inclusions. Type 4 IPG (M29) are rare and consist of intimately intergrown Ms+Prl+Su with parallel or subparallel basal planes. The matrix contains only Ms+Prl and rare Pg. Type 5 (M8) is the most complex type of IPG. These stacks, which may be embedded in a Ms+Prl or Ms+Prl+Su matrix, are 10 characterized by an extremely variable relative abundance of the four phyllosilicates. Chlorite is generally present in IPG as weathered, discontinuous packets surrounded by pyrophyllite and sudoite. Textural relationships between chlorite and muscovite are variable; hematite is present at the border of or inside the IPG. Type (3) and (4) IPG consist of stacks formed on muscovite. Type (5) IPG might actually have formed on an older muscovite or chlorite. Type 6 IPG are mainly composed of sudoite and only occur in the M39 quartzite where they coexist with a Ms+Su+Prl matrix. The similar features and relationships among the intergrown phases observed in the different IPG belonging to types (3), (4), and (5) allow for a summary description (tab.1). Muscovite is characterized by two distinct microstructures: i) lattice fringe images show that Ms is present either as several hundred Ångstrom thick, defect-free packets with straight lattice fringes or as ii) small discrete packets with slightly different orientations along c (Fig.7a-b). Packets with bent, split or interrupted basal planes are characterized by a higher dislocation density. Chemical analyses in different muscovite packets of a single IPG reveal variable compositions; given that the analized areas are structurally homogeneous, we can exclude that this variability is due to contamination by other phases. Pyrophyllite occurs both as the 2M polytype (Fig.8a) and as the 1T polytype. Prl packets are several hundred Ångstrom thick, often undeformed and defect-free (Fig.8b). Pyrophyllite is easily distinguished from muscovite for its different contrast, lack of "mottled structure", and its lattice fringe spacing (9.2 Å Prl; 10 Å Ms). 11 Sudoite electron diffraction patterns show both a one-layer and a two-layer polytype (IPG type (4), (5), and (6)). Both the relative intensity of 00l reflections in SAED and the chemical analyses allow sudoite to be distinguished from trioctahedral chlorite. Sudoite forms packets can be parallel intergrown with Ms (Fig.9a-b) or wedgeshaped and terminating inside a muscovite packet (Fig.10). A one layer polytype of chlorite occurs as a minor phase in type (5) IPG. In some SAED patterns, satellite reflections are visible along c , both in 00l row and in rows with k≠3n. These satellite reflections indicate an ordered stacking sequence: long-period polytypes with 4or 6-layer periodicity can be recognized. The presence of paragonite in type (3) IPG (M7) was determined through microanalysis: electron diffraction patterns of Ms with high Na content revealed the presence of a phase with 9.6 Å-spaced basal planes parallel intergrown with 10 Å-spaced basal planes. Muscovite forms coherent boundaries, low-angle grain boundaries, or incoherent boundaries with the other phyllosilicates both . The lattice fringe image in figure 11 shows a deformed packet of Ms: at the microfold hinge, new-formed muscovite grows with a different orientation. Mineral chemistry Representative chemical analyses are reported in tables 2 and 3. The chlorite composition in the IPG (tab.2) varies with the host rock composition and the mineral assemblage of the IPG (Giorgetti, 12 1995). The X Mg (=Mg/Mg+Fe) is linearly correlated with the rock X Mg and ranges from 0.49 (M62) to 0.58 (M33); total Al varies from 5.50 (M62) to 6.24 (M8): Al-rich chlorite coexists with Prl and Cld, whereas Al-poor chlorite is associated with Ms (and Pg) only. Chl has a constant composition within each individual sample, both in IPG and in the matrix, no matter what the microstructural sites in which it occurs. The X Mg of sudoite (tab.2) is independent of the rock X Mg .and varies from 0.75 to 0.82, with a mean of 0.79. As observed for chlorite, the Al content varies according to the mineral assemblage: Al-rich sudoite coexists with Prl and Cld; Al-poor sudoite is also associated with Chl. Unlike chlorite, muscovite has an extremely variable composition: in a single sample, different muscovite compositions can be found in both the matrix and individual IPG (tab.3a and b). There are differences between matrix Ms and IPG Ms: the compositional range in matrix muscovite is smaller than that in IPG muscovite and, in almost all samples the interlayer occupancy is higher in IPG muscovite. Paragonite and pyrophyllite have an almost ideal composition. Transformation mechanisms The textural relationships described in the previous paragraph are consistent with dissolution and crystallization mechanisms, and no indication of exsolution or spinodal decomposition have been 13 observed. Pristine phyllosilicates give rise to new ones as direct replacement products, without the formation of intermediate phases. Although more than one mechanism can operate during replacement, reactions among phyllosilicates have been modelled after Veblen and Ferry (1983) considering the observed "along-layer" transitions. Chlorite mica. The observed lateral transitions from one 14 Ålayer to one 10 Å-layer or from one 14 Å-layer to two 10 Å-layer are solid-state reactions accompanied by significant chemical changes. In the former, for example, we observe the loss of a brucite-like layer which is replaced by interlayer cations (K , Na ) and the reordening of the octahedral cations from a trioctahedral arrangement to a dioctahedral one. The latter mechanism implies a volume increase with a gain of tetrahedral-like layers and interlayer cations. The possible structural relationship has been schematically illustrated by Veblen and Ferry (1983). The reaction has been modelled for the former mechanism considering chemical compositions observed in IPG M62: Mg 4.5 Fe 4.8 Al 2.7 (Si 5.3 Al 2.7 )O 20 (OH) 16 +1.7K +0.1Na + 0.9Si 4 +12H 2 K 1.7 Na 0.1 (Mg 0.2 Fe 0.2 Al 3.7 )(Si 6.2 Al 1.8 )O 20 (OH) 4 +4.3Mg 4.6Fe 2 + +12H 2 O (1) This transformation entails a loss of divalent cations (Mg Mn 2 ) and of H 2 O, and a gain of K (or Na ) and Si 2 4 , Fe 2 , . As an 14 influx of H ions is needed, the reaction is favoured by an acidic environment. Furthermore, the presence of hematite inside and at the boundaries of IPG -a feature observed in all IPG types- indicates that iron oxides precipitated at high f O 2 conditions. Reaction (1) occurs at constant Al contents; in this particular case, it seems that Al is relatively immobile in the metamorphic environment (Veblen and Ferry, 1983). It is likely that the Chl Pg transformation depends on Na activity in the metamorphic fluid. This reaction, as all the ionic reactions discussed in due course, must occur in equilibrium with a fluid phase which allows the transport of ions. Muscovite Paragonite. Muscovite and paragonite always form discrete phases and a metastable precursor, such as sodiumpotassium mica (Jiang and Peacor, 1993), has never been observed. HR images have never highlighted the direct transition from muscovite to paragonite because the volume change is so small that it can remain undetected. Nevertheless, a nucleation and growth mechanism can be invoked for paragonite formation. A spinodal decomposition mechanism can be ruled out as there are no zones with a modulate texture or composition. The Ms Pg reaction not only involves the Na K substitution, but also a chemical change in the dioctahedral layer. As muscovite is far more phengitic than paragonite, there must also be loss of Mg 2 and Fe 2 and changes in the Si/Al ratio. Muscovite Pyrophyllite. The lateral transition from one 10 Ålayer to one 9.2 Å-layer results in a decrease in volume, as in the case of the Chl transformation. The substitution of Ms by Prl gives 15 partial interlayer (see Fig. 8b) (Page, 1980), and slightly differing lattice constants result in strain contrast along the interfaces (Fig.8b). Reaction (2) has been modelled according to the chemical composition of type 4 IPG (M29): K 1.7 (Mg 0.2 Fe 0.1 Al 3.8 )(Si 6.3 Al 1.7 )O 20 (OH) 4 + 1.7Si 4 Al 4 Si 8 O 20 (OH) 4 +1.7K +0.2Mg 2 +0.1Fe 2 +1.5Al 3 (2) The Al and K produced in reaction (2) are incorporated in a new, low celadonitic muscovite. Muscovite Sudoite. The tansformation between Ms and Su may occur either through a topotactic or a dissolution-crystallization mechanism. Textural evidence indicates that sudoite forms after muscovite: if a 1:1 transition occurs, the dehydration reaction involves the substitution of interlayer K for a trioctahedral layer with a consequent increase in volume. The reaction modelled for sample M8 is: K 1.8 (Mg 0.2 Fe 0.1 Al 3.7 )(Si 6.2 Al 1.8 )O 20 (OH) 4 +12H 2 O+3Mg +0.7Fe 2 +2.2Al 3 2 (Mg 3.2 Fe 0.8 Al 5.9 )(Si 6.2 Al 1.8 )O 20 (OH) 16 +1.8K +12H (3) In these types of IPG there is probably also a Chl Su transformation in which a talc-like layer of the former is substituted by a pyrophyllite-like layer of the latter. Muscovite Kaolinite. At the Ms-Kln boundary, two types of layer transition can occur: 16 1 Ms (10 Å) 2 Kln (14 Å) 2 Ms (20 Å) 3 Kln (21 Å) Although both mechanisms involve an increase in volume, the latter is the most likely. Volume change in the second reaction is minor, in agreement with the lack of strain contrast at the Ms-Kln boundary. Considering the structure of the two phyllosilicates, this reaction can occur via a dissolution-recrystallization mechanism. Structurally, it implies the addition of gibbsite-like sheets and a reversal of the orientation of some tetrahedral sheets of the T-O-T units (Ahn and Peacor, 1987). 2 (K 1.8 (Mg 0.2 Fe 0.2 Al 3.7 )(Si 6.2 Al 1.8 )O 20 (OH) 4 )+ +6H 2 O+4H +Al 3 3 (Al 4 Si 4 O 20 (OH) 8 )+3.6K +0.4Mg 2 +0.4Fe 2 +0.4Si 4 (4) Reaction (4), modelled for IPG M62, produces K cations while Si 4 , H , H 2 O, and Al 3 and bivalent are consumed. It is favoured by an acidic environment; the high chemical activity of H ions could explain the direct transition from Ms to Kln without the formation of mixed layer illite/smectite observed by other authors (Meunier and Velde, 1979; Beaufort and Meunier, 1983; Banfield and Eggleton, 1990). Origin of interleaved phyllosilicate grains 17 Optical and SEM-BSE observations suggest a detrital origin for IPG. Size distribution, morphology, and textural relationships between stacks and cleavage suggest that the IPG originated from pristine grains that were present prior to the development of cleavage. Furthermore, deformation textures such as kinking, bending and cleavage which crosscuts stacks can be interpreted as the result of "weathering" through a combination of metamorphic and tectonic events (Li et al., 1994). The difference in mineralogy between some IPG and the matrix of corresponding samples is further evidence of the detrital origin of the IPG. In addition, we have observed that, unlike chlorite, muscovite has not equilibrated at the sample scale and preserves different detritic compositions. The stacks behave like a microsystem: although the IPG exchange matter with the surrounding matrix, neither textural nor chemical equilibrium is achieved, reflecting a sluggish diffusion rate at low temperature, which determines the small size of the equilibrated domains (Li et al., 1994). TEM data confirms the proposed model and allow the characterization of reaction mechanisms involving phyllosilicates. Topotactic growth is facilitated along the basal planes, but some transformations occur through dissolution-crystallization reactions. Prograde reactions (as Chl Micas, Ms Prl, Ms Pg) lead to a decrease in the volume of solids and, generally, to the production of H 2 O; on the contrary, retrograde reactions (Ms Kln, Ms Su) involve an increase in volume and the consumption of water. Transformations are facilitated by deformation: microfolding and shortening of coarse-grained crystals cause dissolution of detrital 18 phases; new phyllosilicates precipitate in extension sites (splitting of basal planes and hinge regions) originating an assemblage in equilibrium with the new P-T conditions. This process can be clearly observed in figure 11, where a muscovite packet is deformed by a microfold. In this highly deformed region, starting from the fold hinge, new formed muscovite and pyrophyllite crystallize during prograde metamorphism; sudoite topotactically grows on muscovite during the retrograde phase. SEM and TEM images have never revealed the presence of relict phases other than muscovite or chlorite. This feature suggests that: i) either chlorite crystals are detritic or they derive from the complete weathering of an undetected precursor during diagenesis or before the metamorphic peak of the rocks; ii) muscovite crystals represent detrital grains or grains which equilibrated at P-T conditions different from those characterizing peak metamorphism; this interpretation is also confirmed by the different compositional ranges of matrix muscovite and muscovite in the IPG of a single sample. There is no evidence of older precursors, which are often observed by other authors. Many have described chlorite-mica stacks which form on detrital biotite of igneous origin (Dimberline, 1986; White et al., 1985): the shape of stacks sometimes resembles that of amphiboles or pyroxenes, probably derived from volcanic detritus (Milodowski and Zalasiewicz, 1991; Roberts and Merriman, 1990). The chemical and textural characteristics of Verrucano IPG and the lack of expandable layers (corrensite, smectite) strongly indicate that stacks developed during prograde and retrograde paths by direct replacement of pre-existing minerals whose origin remains uncertain. 19 Deformation and fluid circulation triggered the growth of new-formed (i.e. metamorphic) minerals and the new mineral assemblage depends on the chemical composition of the microstructural site. Acknowledgements The authors are grateful to M. M. Abad Ortega from the Scientific Instrument Center of the University of Granada for his help with HRTEM work. Financial support was supplied by the Italian Ministry of University and Scientific and Technological Research grants (MURST to I.M.) and Research Projects nº PB92-0961 and PB920960 of the Spanish Ministry of Education as well as Research Group 4065 of the Junta de Andalucia. The authors also thank B. Grobéty and M. Mellini for their constructive reviews of the paper. 20 References Ahn JH, Peacor DR (1987) Kaolinitization of biotite: TEM data and implications for an alteration mechanism. Am Mineral 72: 353-356 Banfield JF, Eggleton RA (1990) Analytical transmission electron microscope studies of plagioclase, muscovite, and K-feldspar weathering. Clays Clay Miner 38: 77-89 Beaufort D, Meunier A (1983) Petrographic characterization of an argillic hydrothermal alteration containing illite, K-rectorite, Kbeidellite, kaolinite and carbonates in a cupromolybdenic porphyry at Sibert (Rhone, France). Bull Mineral 106: 535-551 Beutner EC (1978) Slaty cleavage and related strain in Martinsburg Slate, Delaware Water Gap, New Jersey. American Journal of Science 278: 1-23 Buseck PR (1992) Principles of transmission electron microscopy. In: Buseck PR (ed) Minerals and reactions at the atomic scale: transmission electron microscopy. Rev in Mineral 27: 1-35 Buseck PR, Cowley JM, Eyring L (1988) High-resolution transmission electron microscopy and associated techniques. Oxford University Press, New York, 128 pp Carmignani L, Kligfield R (1990) Crustal extension in the northern Apennines: the transition from compression to extension in the Alpi Apuane core complex. Tectonics 9: 1275-1303 Craig J, Fitches WR, Maltman AJ (1982) Chlorite-mica stacks in lowstrain rocks from central Wales. Geol Mag 119: 243-256 21 Dimberline AJ (1986) Electron microscope and electron microprobe analysis of chlorite-mica stacks in the Wenlock turbidites, mid Wales, U. K. Geol Mag 123: 299-306 Franceschelli M, Leoni L, Memmi I, Puxeddu M (1986) Regional distribution of Al-silicates and metamorphic zonation in the lowgrade Verrucano metasediments from the Northern Apennines, Italy. J Metamorphic Geol 4: 309-321 Franceschelli M, Mellini M, Memmi I, Ricci CA (1989) Sudoite, a rock-forming mineral in Verrucano of the Northern Apennines (Italy) and the sudoite-chloritoid-pyrophyllite assemblage in prograde metamorphism. Contrib Mineral Petrol 101: 274-279 Franceschelli M, Memmi I, Gianelli G (1991) Re-equilibration of detrital muscovite and the formation of interleaved phyllosilicate grains in low temperature metamorphism, northern Apennines, Italy. Contrib Mineral Petrol 109: 151-158 Giorgetti G (1995) I fillosilicati delle rocce di basso grado metamorfico della Toscana meridionale -composizione, microstrutture, significato petrologico-. Tesi di Dottorato, Siena University. Jiang WT, Peacor DR (1993) Formation and modification of metastable intermediate sodium potassium mica, paragonite, and muscovite in hydrothermally altered metabasites from northern Wales. Am Mineral 78: 782-793 Jullien M, Baronnet A, Goffé B (1996) Ordering of the stacking sequence in cookeite with increasing pressure: An HRTEM study. Am Mineral 81: 67-78 22 Kretz R (1983) Symbols for rock-forming minerals. Am Mineral 68: 277-279 Li G, Peacor DR, Merriman RJ, Roberts B, van der Pluijm BA (1994) TEM and AEM constraints on the origin and significance of chlorite-mica stacks in slates: an example from Central Wales, U. K. J Struct Geol 16: 1139-1157 Meunier A, Velde B (1979) Weathering mineral facies in altered granites: the importance of local small scale equilibria. Mineral Mag 43: 261-268 Milodowski AE, Zalasiewicz JA (1991) The origin and sedimentary, diagenetic and metamorphic evolution of chlorite-mica stacks in Llandovery sediments of central Wales, U. K. Geol Mag 128: 263278 Nieto F, Velilla N, Peacor DR, Ortega-Huertas M (1994) Regional retrograde alteration of sub-greenschist facies chlorite to smectite. Contrib Mineral Petrol 115: 243-252 Page RH (1980) Partial interlayers in phyllosilicates studied by transmission electron microscopy. Contrib Mineral Petrol 75: 309314 Roberts B, Merriman RJ (1990) Cambrian and Ordovician metabentonites and their relevance to the origin of associated mudrocks in the northern sector of the Lower Paleozoic Welsh marginal basin. Geol Mag 127: 31-43 Sorby HC (1853) On the origin of slaty cleavage. Edinburgh New Philosoph Journal 55: 137-148 van der Pluijm BA, Kaars-Sijpesteijn CH (1984) Chlorite-mica aggregates: morphology, orientation, developement and bearing 23 on cleavage formation in very low-grade rocks. J Struct Geol 6: 399-407 Veblen DR, Ferry JM (1983) A TEM study of the biotite-chlorite reaction and comparison with petrologic observation. Am Mineral 68: 1160-1168 Weber K (1981) Kinematic and metamorphic aspects of cleavage formation in very low grade metamorphic slates. Tectonophysics 78: 297-306 White SH, Hugget JM, Shaw HF (1985) Electron-optical studies of phyllosilicate intergrowths in sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. Mineral Mag 49: 413-423 Woodland BG (1982) Gradational development of dominant slaty cleavage, its origin and relation to chlorite porphyroblasts on the Martinsburg Formation, eastern Pennsylvania. Tectonophysics 82: 89-124 Woodland BG (1985) Relationship of concretions and chloritemuscovite porphyroblasts to the development of domainal cleavage in low-grade metamorphic deformed rocks from northcentral Wales, Great Britain. J Struct Geol 7: 205-215 1 sample IPG other matrix minerals Ms-Kln-Chl matrix (<2µm) Ms-Kln-Chl Type 1 (M62) Type 2 (M669) Chl-Ms-Pg Chl-Ms-Pg Qtz+Rt Type 3 (M7) Ms-Prl (+Pg) Ms-Prl-Su (+Pg) Qtz+Cld+ Hem+Rt+Ilm Chl, defect-free and well crystallized (1, 4layer); hundreds Å thick Ms, defect-free (2M); hundreds Å thick Type 4 (M29) Ms-Prl-Su Ms-Prl (+Pg) Qtz+Cld+ Hem+Rt Ms, defect-free (2M); hundreds Å thick Type 5 (M33) Ms-Prl-Chl-Su Ms-Prl-Su Qtz+Cld+ Hem+Mag+Rt Ms, defect-free (2M); hundreds Å thick Type 5 (M8) Type 6 (M39) Ms-Prl-Chl-Su Ms-Prl Ms-Su Ms-Su-Prl Qtz+Cld+ Hem+Rt Qtz+Hem+Rt+ Ilm Ms, defect-free (2M); hundreds Å thick Qtz+Cal+Dol +Hem+Rt TEM data: main mineral in IPG Chl, defect-free and well crystallized (1, 4l.); hundreds Å thick TEM data: integrown mineral Ms (2M); isolated l. or hundreds Å thick -lateral transtitions with Chl, l.a.g.b. with Chl Ms (2M); isolated l. or hundreds Å thick -lateral transtitions with Chl, l.a.g.b. with Chl Ms, highly defective (2M), tens Å thick; -l.a.g.b. with the defect-free Ms Su (1, 2-l.); tens, hundreds Å thick; -c.g.b. or h.a.g.b. with Ms Su: as in type 4 IPG Kln (1T); tens, hundreds Å thick; -lateral transtitions with Ms, and l.a.g.b. with Ms Pg (2M); isolated l. or hundreds Å thick -c.g.b. with Ms, l.a.g.b. with Chl Prl (1T, 2M), hundreds Å thick; -lateral transtitions with Ms, l.a.g.b. with Ms Pg (2M), tens Å thick -c.g.b. with Ms Prl: as in type 3 IPG Prl: as in type 3 and 4 IPG Chl (1, ,6-l.); hundreds Å thick; -lateral transition and l.a.g.b. with Ms Su (1-l.); tens, hundreds Å thick; -c.g.b., l.a.g.b., and h.a.g.b. with Ms tab.1. Mineral assemblages of IPG and associated matrices of the studied samples. Minerals in brackets are extremely rare. Mineral symbols are from Kretz (1983); Su = sudoite. l. = layer; in brackets: polytype (es.: 1 l.= 1 layer polytype; 2M = 2M plytype); thickness refers to mineral packet thickness. l.a.g.b. = low angle grain boundary; h.a.g.b. = high angle grain boundary; c.g.b. = coherent grain boundary; i.g.b. = incoherent grain boundary. 1 Tab.2 Chl M62 24.97 21.94 26.17 14.21 Chl M669 25.63 23.55 24.68 13.33 87.29 87.19 Si AlIV AlVI Fe Mg Mn 5.31 2.69 2.81 4.65 4.50 XMg 0.49 SiO2 Al2O3 FeO MgO MnO total Chl M33 25.58 25.54 19.10 15.42 0.27 86.01 Chl M8 Su M29 26.75 37.14 26.33 35.29 19.58 4.60 14.91 11.08 0.46 88.03 88.11 Su M33 33.66 35.27 6.31 11.89 Su M39 33.25 36.01 5.24 12.18 87.13 86.68 5.38 2.62 3.22 4.33 4.17 5.28 2.72 3.48 3.29 4.74 0.05 5.38 2.62 3.62 3.29 4.47 0.08 6.63 1.37 6.05 0.69 2.95 6.17 1.83 5.79 0.97 3.25 6.10 1.90 5.88 0.80 3.33 0.49 0.58 0.57 0.81 0.77 0.81 tab.2. Representative chemical analyses of chlorite and sudoite in the studied IPG. Structural formulae are calculated on the basis of 28 oxygens; all Fe as FeO. XMg= Mg/(Mg+Fe). Tab.3 SiO2 TiO2 Al2O3 FeO MgO CaO Na2O K2O total Si AlIV AlVI Ti Fe Mg Ca Na K M62 47.42 0.96 36.13 1.56 0.85 M62 48.80 0.40 33.11 2.88 1.36 M669 46.64 0.67 35.82 1.77 0.65 M669 48.75 M7 48.18 0.16 35.11 1.37 0.78 M29 47.08 0.51 37.35 0.44 0.45 M29 47.75 32.67 2.67 1.58 M7 47.14 0.16 36.47 1.42 0.49 0.57 10.24 10.68 97.73 97.23 0.43 10.07 96.05 0.60 9.57 95.84 1.11 8.78 95.57 0.49 9.39 95.48 1.54 8.64 96.01 0.76 9.22 95.96 6.15 1.85 3.67 0.09 0.17 0.16 6.40 1.60 3.51 0.04 0.32 0.26 6.15 1.85 3.72 0.07 0.19 0.13 6.45 1.56 3.54 6.33 1.67 3.77 0.02 0.15 0.15 6.13 1.87 3.87 0.05 0.05 0.09 6.31 1.70 3.70 0.29 0.31 6.19 1.81 3.84 0.02 0.16 0.10 0.14 1.69 1.79 0.11 1.69 0.15 1.61 0.28 1.47 0.12 1.57 0.39 1.43 0.19 1.61 36.28 1.41 0.54 0.29 0.11 M33 46.45 0.64 36.00 1.03 0.52 0.11 1.22 8.77 94.74 M33 50.30 6.16 1.84 3.78 0.06 0.11 0.10 0.02 0.31 1.48 6.59 1.41 3.60 32.39 1.89 1.54 0.14 0.29 9.18 95.73 0.21 0.30 0.02 0.07 1.53 M8 46.09 0.15 37.27 1.21 0.47 0.11 1.27 8.42 94.99 M8 47.84 0.53 33.41 2.27 1.66 M39 47.07 0.49 37.04 0.69 0.79 M39 48.66 0.59 32.97 2.21 1.69 0.39 1.41 10.32 8.79 96.42 96.28 0.27 10.57 96.96 6.08 1.92 3.88 0.01 0.13 0.09 0.02 0.32 1.42 6.31 1.69 3.51 0.05 0.25 0.33 6.13 1.87 3.81 0.05 0.07 0.15 6.38 1.62 3.48 0.06 0.24 0.33 0.10 1.74 0.36 1.46 0.07 1.77 tab.3. Representative chemical analyses of muscovite in the studied IPG: for each sample, muscovites with the maximum and with the minimum 2 celadonitic substitution are reported. Structural formulae are calculated on the basis of 22 oxygens; all Fe as FeO. FIGURE CAPTIONS Fig.1. Sketch map of Verrucano outcrops in the northern Apennines. Studied samples are from Monticiano-Roccastrada and M. Leoni outcrops. 3 Fig.2. Back-scattered electron image showing an IPG (sample M8) composed of Ms-Prl-Chl-Su with some hematite crystals along the rim; the grain is strongly altered. Fig.3. Representative chlorite from type (1) IPG (sample M62). a: lattice image of Chl showing 14Å-layers with coherently intergrown single 10Å- layer (indicated by the arrow); b: corresponding SAED pattern. Superstructure reflections are visible in the rows with k≠3n; probably L4 type sequence according to Jullien et al. (1996) may be recognized; c: transition from one 10Å-layer to two 14Å-layer (enlargement of the area indiacted by the arrow in a). 4 Fig.4. a: image of intergrown chlorite and mica packets in type (2) IPG (sample M669); b: AEM analyses of chlorite and muscovite (type 2 IPG) plotted in the Si-Al-Mg+Fe diagram (based on cation proportions); the mixedlayer compositions lie on the line between mica and chlorite. 5 Fig.5. a: lattice image of muscovite (10Å and 20Å periodicities are visible) with the tipical "mottled structure" (sample M669); b: SAED pattern of parallel intergrown Pg (9.6Å) and Ms (10Å) (2-layer polytypes); splitting of 00l reflections is evident. 6 Fig.6. Textural relationships between Kln and Ms (sample M62). a: SAED pattern showing 7Å-reflections of two differently oriented Kln crystals; one of them has [001] parallel with that of a Ms crystal; b: corresponding lattice image of a several hundred Å-thick packet of Kln, parallel intergrown with a muscovite packet; relicts of 10Å-layers are indicated (arrow). c: enlargement of the circled area in b showing the lateral transition from 7Ålayers to 10Å-layers (thin arrow); thick arrow indicate a relict of a 10Å-layer inside the Kln packet. 7 Fig.7. a: lattice image of muscovite packets showing low-angle grain boundaries (arrow; type 4 IPG, sample M29); b: corresponding SAED pattern showing at least three Ms crystals with different orientations; splitting of 00l reflections indicates the presence of discrete Pg packets. Fig.8. a: image of pyrophyllite in type (3) IPG (sample M7) showing 9.2Ålayers with relicts of 10Å-layers (arrows); strain contrast is visible in relation to layer terminations. b: SAED pattern of Prl (two-layer polytype) parallel intergrown with muscovite (10Å reflections along the 00l row). 8 Fig.9. a: lattice image of type 6 IPG showing alternating Su (14Å periodicities are visible) and Ms packets; these packets are generally parallel intergrown with coherent contacts: on the right side of the image a sudoite packet abuts inside a muscovite packet. b: SAED pattern of parallel intergrown sudoite and muscovite. 9 Fig.10. Image of a wedge-shaped packet of sudoite (14Å-layer) terminating inside a muscovite packet (type 4 IPG): basal plane of muscovite are bent at the wedge termination (sample M29). Fig.11. TEM image of a microfold in a Ms packet (sample M29): from the fold hinge new muscovite grows, a low-angle grain boundary between Ms and Prl is also visible (arrow) in the corresponding SAED pattern which shows two Ms and one Prl crystals with slightly different orientation.