Status of Wisconsin Agriculture 2004 (Word document)

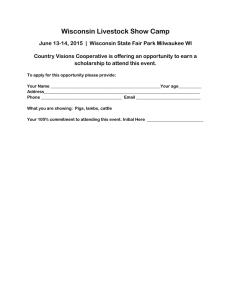

advertisement