Manuscript_Moran_L_SRR_R2.doc

advertisement

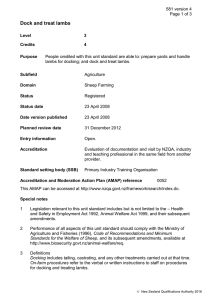

1 1 2 Metabolic acidosis corrected by including antioxidants 3 in diets of fattening lambs 4 5 Lara Morán, F. Javier Giráldez*, Raúl Bodas1, Julio Benavides, Nuria 6 Prieto, and Sonia Andrés 7 8 Instituto de Ganadería de Montaña (CSIC-Universidad de León). Finca Marzanas. E- 9 24346 Grulleros, León (Spain). 10 11 *CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: F. Javier Giráldez, Instituto de Ganadería de Montaña 12 (CSIC-ULE). Finca Marzanas. E-24346 Grulleros, León, Spain. Tel. +34 987 317 156 13 Fax +34 987 317 161 E-mail: j.giraldez@eae.csic.es 14 1 Present address: Instituto Tecnológico Agrario, Junta de Castilla y León. Finca Zamadueñas. Ctra. Burgos, km. 119. 47071 Valladolid (Spain). 2 15 Abstract 16 Thirty-two Merino lambs fed barley straw and a concentrate alone (CONTROL) or 17 CONTROL enriched with vitamin E (0.6 g kg-1 of concentrate, VITE006) or carnosic 18 acid (0.6 g kg-1 of concentrate CARN006; 1.2 g kg-1 of concentrate, CARN012) were 19 used to assess the effect of these antioxidant compounds on metabolic acidosis. After 7 20 wk of being fed the experimental diets, the pH of blood samples was lower (P=0.012) 21 for the CONTROL lambs than groups fed antioxidants. Metabolic acidosis in fattening 22 lambs was corrected by both antioxidants (carnosic acid and vitamin E). 23 Keywords: carnosic acid; vitamin E; acidosis; oxidative stress; lamb 24 1. Introduction 25 With intensive production systems, animals may be stressed by acidogenic diets 26 (Berkemeyer, 2009) fed to meet high metabolic demands. Under this situation, reactive 27 oxygen species (ROS) production at the mitochondrial level might be increased, 28 whereas the mitochondrial energy production (ATP) would be partially inhibited 29 (Boveris et al., 2010). Therefore, pyruvate would be partially directed towards lactic 30 acid production and converted to CO2;, thus hypercapnia would be corrected by 31 activation of the respiratory control system (Berkemeyer, 2009). However, experiments 32 in rats have demonstrated that high levels of ROS might disrupt the respiratory control 33 (Mulkey et al., 2003), avoid compensation for hypercapnia and worsen metabolic 34 acidosis promoted by the diet. To our knowledge, no studies have been carried out in 35 ruminants. Consequently, the aim of the present study was to determine if including 36 antioxidants (vitamin E or carnosic acid, a potent antioxidant extracted from 37 Rosmarinus officinalis L., an herb which is commonly used as a flavouring and 38 medicinal plant widely around the world) in the diet for fattening lambs might 3 39 neutralize the negative consequences of ROS, thus correcting the metabolic acidosis 40 caused by the high-grain diets. 41 2. Materials and methods 42 2.1. Animals and diets 43 After stratification on the basis of body weight (mean body weight (BW), 15.2 ± 44 0.749 kg), 32 male Merino lambs were allocated randomly to four different groups: a 45 control group (CONTROL), a group fed vitamin E (α- tocopheryl acetate) at a rate of 46 0.6 g kg-1 of concentrate (VITE006, equivalent to 900 IU of vitamin E kg-1 of 47 concentrate), a third group fed the same dose (0.6 g kg-1 of concentrate, CARN006) of 48 carnosic acid (Shaanxi Sciphar Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Xi'an, China) and a fourth 49 group fed double the low dose of carnosic acid (1.2 g carnosic acid kg-1 of concentrate, 50 CARN012). The animals were individually penned. All handling practices followed the 51 recommendations of the European Council Directive 86/609/EEC for the protection of 52 animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes. 53 The basal diet was composed of concentrate [dry matter (DM) 888 g kg-1, crude 54 protein (CP) 178 g kg-1 DM, neutral detergent fibre (NDF) 134 g kg-1 DM, and ash 56 g 55 kg-1 DM] and barley straw (DM 913 g kg-1, CP 35 g kg-1 DM, NDF 757 g kg-1 DM, ash 56 55 g kg-1 DM). After 7 days of adaptation to the basal diet (barley straw and the 57 concentrate with no antioxidants), all lambs were fed barley straw plus one of the four 58 concentrates above for 7 wk. The concentrate (35 g kg-1 BW day-1) and forage (200 g 59 day-1) were weighed and supplied in separate feeding troughs at 9:00 h every day; fresh 60 drinking water was always available. The orts (<5% of the total diet) were weighed 61 daily. The lack of significant differences in feed intake and performance of the animals 62 [concentrate (P=0.912) or barley straw (P=0.715) intake; average daily gain (P=0.691) 63 and feed to gain ratio (P=0.566)] is addressed in Morán et al. (2012a). 4 64 2.2. Blood, liver and rumen sampling 65 After 7 wk of being fed the experimental diets blood samples collected by jugular 66 venipuncture into lithium heparin tubes were assayed in a Stat Profile pHOx Plus blood 67 analyser (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA, USA) for pH, bicarbonate (HCO3-), CO2 68 pressure (pCO2), anion Gap, total CO2 (tCO2), and Na+, K+ and Cl- concentrations an 69 hour after being sampled. Finally, all lambs underwent food withdrawal during 6 h 70 before being slaughtered, then they were weighed, stunned, slaughtered by 71 exsanguination from the jugular vein, eviscerated and skinned (Morán et al., 2012b). A 72 piece of liver was excised and held at -80 ºC for TBARS analysis (Bodas et al., 2012). 73 Rumen fluid was strained through four layers of cheesecloth and pH was determined 74 immediately. Two pieces of the rumen wall [posterior dorsal (PDR) and anterior ventral 75 (AVR) areas] were placed in 10% formalin for further anatomical study (López-Campos 76 et al., 2012). 77 2.3. Statistical analysis 78 Data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance with the fixed effect of 79 treatment as the only source of variation, using the GLM procedure of the SAS package. 80 Orthogonal contrasts were performed to test the effects of antioxidants supplementation 81 (CONTROL vs. CARN006+CARN012+VITE006), vitamin E vs. carnosic acid 82 (VITE006 vs. CARN006+CARN012) and level of carnosic acid (CARN006 vs. 83 CARN012). 84 3. Results 85 3.1. Blood gases, acid-base parameters and liver antioxidant status (TBARS) 86 Table 1 presents the blood gases, acid base profile and liver antioxidant status 87 (TBARS) of the lambs. The lambs in the CONTROL group had lower blood pH values 5 88 when compared to the lambs fed antioxidants (P=0.012). Differences (P<0.05) between 89 the CONTROL and the antioxidants groups also were observed for pCO2, anion gap, K+ 90 and TBARS. In addition, lambs fed antioxidants had higher blood pH and lower pCO2, 91 anion Gap and K+ when compared to the CONTROL group. Lambs fed vitamin E had 92 lower TBARS than the average of lambs fed carnosic acid. Compared to the low level 93 of carnosic acid (CARN006), the high level decreased blood HCO3-, tCO2 and Na+. 94 95 [INSERT TABLE 1 NEAR HERE, PLEASE] 3.2. Ruminal pH and anatomopathological study of ruminal wall 96 The ruminal pH values (overall mean values 5.52 ± 0.082) reflected ruminal acidosis 97 for all of the animals of the present study. Moreover, the interior of the rumen wall was 98 grey to dark in all of the animals (characteristic of parakeratosis). This lack of effect of 99 antioxidants on inflammation of ruminal ephitelium was corroborated by the lack of 100 differences in the mucose (AVR, overall mean values 0.68 ± 0.253 mm; PDR, overall 101 mean values 0.82 ± 0.161 mm) and submucose thickness (AVR, overall mean values 102 0.69 ± 0.099 mm; PDR, overall mean values 0.71 ± 0.115 mm) and the anastomosis and 103 number of papillae (AVR, overall mean values 81.1 ± 4.80 papillae cm-2; PDR, overall 104 mean values 95.9 ± 8.10 papillae cm-2). 105 4. Discussion 106 Feeding high-grain diets to growing lambs to achieve maximum growth rates often is 107 associated with ruminal acidosis (local), as was apparent for all the lambs in the present 108 study (anatomopathological study of the ruminal wall). Absorbed into the bloodstream, 109 the acid (H+) reduces blood pH (normal range of 7.36–7.44) to a more acidic state 110 (metabolic acidosis, which is not local but systemic), so blood pH can be considered as 111 an indicator of ruminal acidosis (Horn et al., 1979). In the present study only the lambs 112 of the CONTROL group showed latent metabolic acidosis (Table 1), that is to say, a 6 113 blood pH constantly at the low end of the normal range and a high anion Gap 114 (Berkemeyer, 2009). In contrasts, lambs fed antioxidants, despite ruminal acidosis, did 115 not exhibit metabolic acidosis (Table 1). These results are consistent with those of 116 Vestweber et al. (1974) who reported mean blood pH of 7.44 and 7.36, respectively, 117 before and after producing acute acidosis in sheep. 118 Reduction in liver TBARS for lambs receiving CARN012 and VITE006 highlights 119 the ability of these compounds to improve the antioxidant status (Table 1). The 120 relationship between metabolic acidosis and oxidative stress (Mobbs, 2007) is apparent 121 from a mitochondrial point of view; the electron transport chain and the oxidative 122 phosphorylation (O2 is consumed to produce H2O and ATP) are coupled by a proton 123 (H+) gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane known as the proton-motive 124 force (∆p). This gradient is used by the FOF1 ATP-synthase complex to make ATP via 125 oxidative phosphorylation. However, 1% of the mitochondrial electron flow leads to the 126 formation of ROS (O2•–) under normal physiological conditions. This percentage is 127 increased when H+ leakage (passive diffusion of H+ with no ATP production) increases 128 due to accumulation of H+ (Boveris et al., 2010), as happens during metabolic acidosis. 129 In acidosis, O2 is channeled to ROS production, which reacts with various cellular 130 targets changing membrane excitability, synaptic transmission, gene induction and 131 cellular metabolism. 132 As a result, ATP production is reduced when H+ leaks during metabolic acidosis 133 (Berkemeyer, 2009). Pyruvate is diverted toward lactate production and most of the 134 lactate is converted into CO2, promoting hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis. To 135 compensate for this situation, the hypoxic/hypercapnic chemoreflex is activated; 136 however, if hyperventilation takes place (as happens when ROS are augmented, as will 137 be explained below), the binding tenacity of haemoglobin for oxygen increases, and less 7 138 oxygen is released for cells (the Bohr Effect). Consequently, cells produce lactic acid 139 and the body continues to be exposed to organic acid with no recovery (lactic acid trap; 140 Berkemeyer, 2009). These effects would explain the high pCO2 (hypercapnia) and low 141 pH (latent acidosis) observed in the CONTROL lambs (Table 1). 142 As previously stated, hypercapnia is one stimulus but not the only for the respiratory 143 control system (Mulkey et al., 2003). In fact, the respiratory control might be disrupted 144 by oxidation stress of the brain stem respiratory control centre (possibly CO2/H+ 145 chemosensitive neurons). For example, hyperoxia (Mulkey et al., 2003) and chemical 146 oxidants (Lipton et al., 2001) increase respiration rate, whereas antioxidants can block 147 the effects of hyperoxia (Mulkey et al., 2003). Consequently the lambs in the 148 CONTROL group presumably suffered from hyperventilation (lactic acid trap), while 149 antioxidant fed lambs would have neutralized the negative effects of ROS at the 150 respiratory control centre. 151 The low concentrations of plasma K+ in the antioxidant groups when compared to the 152 CONTROL corroborate this theory (Table 1). Neurons are stimulated by a free radical- 153 dependent mechanism, possibly inhibiting a K+ channel taking charge of maintaining 154 low extracellular potassium concentrations, which are necessary to preserve potassium 155 gradients across cell membranes (essential for nerve excitation) (Hoshi and Heinemann, 156 2001; Mulkey et al., 2003). Specifically, the oxidation of methionine to methionine 157 sulfoxide during ROS production is one of the main factors involved in the inactivation 158 process of the ion channels (Hoshi and Heinemann, 2001). Thus, the high concentration 159 of plasma potassium in the CONTROL group may indicate that cell uptake of potassium 160 was impaired by ROS production. On the other hand, the normal values of pH, anion 161 Gap, pCO2 and K+ in the lambs fed antioxidants indicate that these compounds helped 162 to detoxify ROS, and attenuate the deleterious consequences of metabolic acidosis. 8 163 5. Conclusions 164 Including antioxidants in the diet of fattening lambs had no detectable effect on 165 ruminal acidosis. However, metabolic acidosis was corrected when either carnosic acid 166 or vitamin E was added to the concentrate being fed. Consequently, supplements of both 167 compounds should help preserve acid-base status of fattening lambs fed high-grain 168 diets. 169 Acknowledgments 170 Financial support received project AGL2010-19094 is gratefully acknowledged. Raúl 171 Bodas, Nuria Prieto, Julio Benavides (JAE-Doc contracts) and Lara Morán (JAE pre- 172 doc grant) were supported by the programme ‘Junta para la Ampliación de Estudios’ 173 (CSIC-European Social Fund). 174 References 175 Berkemeyer, S., 2009. Acid-base balance and weight gain: are there crucial links via 176 protein and organic acids in understanding obesity? Med. Hypotheses 73, 347-356. 177 Bodas, R., Prieto, N., Jordán, M.J., López-Campos, Ó., Giráldez, F.J., Morán, L., 178 Andrés, S., 2012. The liver antioxidant status of fattening lambs is improved by 179 naringin dietary supplementation at 0.15% rates but not meat quality. Animal 6, 180 863-870. 181 Boveris, A., Carreras, M.C., Poderoso, J.J., 2010. The Regulation of Cell Energetics and 182 Mitochondrial Signaling by Nitric Oxide, in: Ignarro, L.J., (Ed.), Nitric Oxide: 183 Biology and Pathobiology. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 441 - 482 184 Horn, G.W., Gordon, J.L., Prigge, E.C., Owens, F.N., 1979. Dietary buffers and ruminal 185 and blood parameters of subclinical lactic acidosis in steers. J. Anim. Sci. 48, 683– 186 691. 9 187 188 Hoshi, T., Heinemann, S.H., 2001. Regulation of cell function by methionine oxidation and reduction. J. Physiol. 531, 1-11. 189 Lipton, A.J., Johnson, M.A., McDonald, T., Lieverman, M.W., Gozal, D., Gaston, B., 190 2001. S-nitrosothiols signals the ventilatory response to hypoxia. Nature 413, 171- 191 174. 192 López-Campos, Ó., Bodas, R., Prieto, N., Giráldez, F:J., Pérez, V., Andrés, S., 2010. 193 Naringin dietary supplementation at 15% rates does not provide protection against 194 sub-clinical acidosis and does not affect the responses of fattening lambs to road 195 transportation. Animal 4, 958-964. 196 197 Mobbs, C., 2007. Oxidative stress and acidosis, molecular responses to, in: Finck, G., (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Stress. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, p. 49. 198 Morán, L., Andrés, S., Bodas, R., Benavides, J., Prieto, N., Pérez, V., Giráldez, F.J., 199 2012a. Antioxidants included in the diets of fattening lambs: effects on immune 200 response, stress, welfare and distal gut microbiota. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 173, 201 177-185. 202 Morán, L., Andrés S., Bodas, R., Prieto, N., Giráldez, F.J., 2012b. Meat texture and 203 antioxidant status are improved when carnosic acid is included in the diet of 204 fattening lambs. Meat Sci. 91, 430-434. 205 Mulkey, D.K., Henderson, R.A., Putnam, R.W., Dean, J.B., 2003. Hyperbaric oxygen 206 and chemical oxidants stimulate CO2/H+-sensitive neurons in rat brain stem slices. 207 J. Appl. Physiol. 95, 910–921. 208 209 Vestweber, J.G.E., Leipold, H.W., Smith, J.E., 1974. Ovine ruminal acidosis: clinical studies. Am. J. Vet. Res. 35, 1587-1590. 10 210 Table 1 211 212 Blood gases, acid base profile and liver antioxidant status (TBARS) in not supplemented fattening lambs (CONTROL) or supplemented either with carnosic acid (0.6 and 1.2 g kg-1 concentrate) or vitamin E (0.6 g kg-1 concentrate) Parameter1 213 214 215 216 Orthogonal contrasts2 Dietary treatment (n=8) CONTROL CARN006 CARN012 VITE006 sed C vs. AO VE vs. CA C06 vs. C12 pH (ven) 7.38a 7.42b 7.42b 7.41b 0.013 0.001 0.482 0.635 HCO3- (ven) (mmol/L) 25.3 26.8 25.2 26.3 0.74 0.218 0.581 0.045 pCO2 (ven) (mmHg) 46.6b 44.1ab 42.3a 44.6ab 1.37 0.022 0.246 0.194 Anion Gap (mmol/L) 15.4b 13.5a 14.0ab 13.3a 0.67 0.004 0.382 0.468 tCO2 (ven) (mmol/L) 26.7 28.1 26.4 27.7 0.77 0.295 0.521 0.045 Na+ (mmol/L) 146 147 145 145 0.7 0.484 0.217 0.042 K+ (mmol/L) 4.87b 4.56a 4.38a 4.38a 0.126 0.001 0.418 0.176 Cl- (mmol/L) 110 111 110 110 0.6 0.944 0.095 0.214 TBARS (µg MDA g-1 liver) 1.65b 1.58b 1.21ab 0.77a 0.244 0.053 0.010 0.207 1 HCO3-: bicarbonate; pCO2: CO2 pressure; tCO2: total CO2 Orthogonal contrasts: C vs. AO = CONTROL vs. CARN006+CARN012+VITE006; VE vs. CA = VITE006 vs. CARN006+CARN012; C06 vs. C12 = CARN006 vs. CARN012. a, b : different subscripts in the same row indicate significant differences (P<0.05) between diets. 2