canjzoombtact00.doc

Diurnal behaviour and habitat use of nonbreeding

Marbled Teal, Marmaronetta angustirostris

Andy J. Green and Mustapha El Hamzaoui

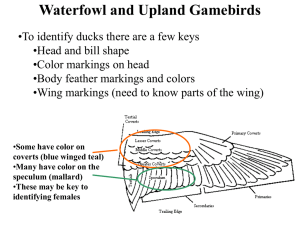

Abstract : The diurnal behaviour and habitat use of the globally threatened Marbled Teal, Marmaronetta angustirostris , were studied in Morocco and Spain from October to March. This is the first study of nonbreeding Marbled Teal, the most primitive member of the pochards (tribe Aythyini). Like other Aythyini, Marbled Teal pair relatively late: only

35% of individuals were paired by mid-March. Feeding was mainly nocturnal, and less than 2% of daytime was spent feeding from November to March. Feeding behaviour was similar to that of dabbling ducks (tribe Anatini). A steady increase in swimming activity from October to March was related to increased courtship activity and raptor-avoidance behaviour. Teal selected areas close to the shoreline and avoided open water. Selection of shoreline habitats and dis- tance to shoreline covaried with month and behaviour type. The Marbled Teal is an aberrant pochard with a stronger ecological affinity with the Anatini.

Résumé : Nous avons étudié le comportement diurne et l’utilisation de l’habitat chez la Marmaronette marbrée, Mar- maronetta angustirotris, au Maroc et en Espagne, d’octobre à mars; il s’agit d’une espèce menacée dans toute sa répar- tition. Ce travail constitue la première étude, hors de la période de reproduction, de la Marmaronette marbrée, espèce la le plus primitive des Aythyini. Comme chez les autres Aythyini, l’accouplement est relativement tardif chez la Mar- maronette marbrée et seulement 35 % des individus avaient un partenaire au milieu de mars. L’alimentation s’est avérée surtout nocturne et, de novembre à mars, moins de 2 % de la période diurne était consacrée à l’alimentation. Le comportement alimentaire des marmaronettes était semblable à celui des canards barboteurs (Anatini). L’augmentation progressive de l’activité de nage observée d’octobre à mars était reliée à l’augmentation de la fréquence des comporte- ments de cour et à la fuite des rapaces. Les oiseaux se tenaient surtout près de la côte et évitaient les zones d’eau libre. La préférence pour les habitats côtiers et la distance jusqu’à l’eau étaient en covariation avec le mois et le com- portement. La Marmaronette marbrée est un oiseau aberrant dans sa catégorie et a des affinités écologiques plus mar- quées avec les Anatini.

[Traduit par la Rédaction]

Introduction

In North America, the dabbling ducks (tribe Anatini) and diving ducks or pochards (tribe Aythyini) are considered to fall into two distinct guilds throughout the annual cycle

(e.g., Nudds 1983, 1992; Nudds and Wickett 1994). The structure of Anatidae communities in the Mediterranean region has been less studied, but is complicated by the pres- ence of Aythyini that show ecological affinities with the

Anatini (Amat 1984; Livezey 1996; Green 1998 a ), particu- larly the Marbled Teal, Marmaronetta angustirostris , consid- ered the most primitive living member of the Aythyini

(Livezey 1996). Recently, the first detailed studies of the breeding ecology of this globally threatened species have been made (Green 1998 a ; Green et al. 1999 a ). Here we

Received January 19, 2000. Accepted August 10, 2000.

A.J. Green.

1 Estación Biológica de Doñana, Department of

Applied Biology, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones

Científicas, Avenida María Luisa s/n, 41013 Sevilla, Spain.

M. El Hamzaoui.

2 Centre National de la Recherche

Forestière, Charia Omar Ibn Al Khattab, B.P. 763,

10050 Rabat-Agdal, Morocco.

1 Author to whom all correspondence should be addressed

(e-mail: andy@ebd.csic.es).

2 Present address: 6850 Deer Run Drive, Alexandria,

VA 22306, U.S.A.

present the first study of its nonbreeding ecology, providing basic information vital for the conservation of the species.

Our objectives were ( i ) to calculate time–activity budgets of Marbled Teal to assess how their diurnal behaviour and rhythms change between October and March, ( ii ) to assess their selection of the different wetland microhabitats avail- able, and how this habitat use covaries with behaviour,

( iii ) to identify their pairing chronology. Northern hemi- sphere Anatini and Aythyini typically form pair bonds anew each year (Oring and Sayler 1992). The Marbled Teal is highly unusual among northern hemisphere ducks in its sex- ual monochromatism and various features of its reproductive biology (Green 1998 c ), but no information was available about its pairing chronology. We compare our results with those from studies of other Aythyini and Anatini to shed light on the ecological similarities of Marbled Teal and on implied trends in the evolution of Anatidae (Livezey 1986,

1991, 1996).

Study areas

Data were collected at Sidi Bou Ghaba (SBG, 34°10′ N,

6°39′ W), a brackish closed-basin lagoon with a length of

6 km and an area of 100 ha among dunes on the Atlantic coast of northwest Morocco (Fig. 1) protected as a Ramsar

Site within a Biological Reserve covering 702 ha (Thévenot

1976; Morgan 1982; Hughes and Hughes 1992). SBG is

Green and El Hamzaoui 2113

Fig. 1. Location of Sidi Bou Ghaba (SBG) in Morocco (2) and Lucio de la FAO in Spain (1), and details of SBG, showing the three lagoon sections described in the text (A, B, and C) and the mouth of the Oued (River) Sebou.

2114 Can. J. Zool. Vol. 78, 2000

Table 1. Diurnal time–activity budgets of Marbled Teal, Marmaronetta angustirostris , in different months at Sidi Bou Ghaba (SBG) and Lucio de la FAO (FAO).

Behaviour

October, SBG

( n = 12)

November, FAO

( n = 11)

February, SBG

( n = 12)

March, SBG

( n = 12)

Sleeping

Loafing

Comfort

Feeding

Swimming

Flying

Aggression

Courtship

Other a

44.9±6.0

16.5±2.7

17.4±1.7

13.9±5.7

4.9±1.3

1.3±1.1

0.1±0.1

0.1±0.1

0.9±0.7

63.9±4.9

5.3±1.0

19.8±2.7

1.2±0.5

8.8±2.9

0

0.8±0.4

0

0.1±0.1

32.3±8.8

33.1±5.8

11.7±3.5

0.1±0.1

21.8±3.5

0.5±0.3

0.1±0.1

0.3±0.2

0.1±0.1

13.3±2.4

25.9±1.8

21.9±2.3

1.6±1.5

31.7±2.2

4.2±0.5

0.8±0.2

0.5±0.5

0

Note: Values, which are given as the mean ± SE, are percentages of time spent in each behaviour; n is the number of diurnal hourly periods.

a

Includes walking, drinking, and alert behaviour.

extremely important for Marbled Teal (hereinafter teal) in the nonbreeding season, but fewer than 10 pairs breed there and no nesting activity occurs before April (Green 1993,

1998 c ).

Water levels undergo major seasonal and annual variations and the lagoon is divided into three parts (Fig. 1): (A) a small permanent section (used by teal during the breeding season only) isolated by a causeway; (B) a deeper (maxi- mum 2.5 m), permanent brackish section subject to consid- erable human disturbance (local residents picnic at the site);

(C) a shallow, temporary brackish to saline section (maxi- mum depth 0.7 m) strictly protected as a reserve. Emergent vegetation is restricted to a dense fringe along the shoreline, and waterbirds are readily observed through gaps in this fringe vegetation and from surrounding elevated vantage points (Fig. 1). Spot conductivity measurements were 14 mS

(19 February 1995) and 13 mS (19 October 1997) in section

B and 46 mS (13March 1995) and 29 mS (19 October 1997) in section C.

A.J.G. also collected comparative data in Lucio de la FAO

(hereinafter FAO), an artificial lake 60 ha in area (fed by wa- ter extracted from an underlying aquifer) inside the northern edge of Doñana National Park (37°05′ N, 6°23′ W) in south- west Spain (Fig. 1). Spot conductivity measurements were

0.6–3.2 mS (15 November 1995). Data were collected dur- ing drought, when these teal occur particularly rarely in

Spain (Green and Navarro 1997). Ringing recoveries suggest that birds at FAO and SBG are members of the same migra- tory population (Navarro and Robledano 1995).

Methods

Behaviour and habitat use

Data were collected throughout the daylight period by means of instantaneous flock-scan sampling with a telescope (Altmann

1974). At SBG, flock scans were conducted at 30-min intervals by up to two observers who changed position during scans to cover all areas in use by teal. A few individuals were sometimes overlooked

(e.g., sightings were obstructed by vegetation). Data were collected on 8 days between 12 and 21 February 1995, on 5 days between 12 and 21 March 1995, and on 17 and 18 October 1997; scans were scheduled scans to ensure equal coverage for each hour of the day.

For each teal we recorded behaviour (see below); distance to the shoreline (inner edge of the fringe of emergent vegetation (Fig. 1), or the bank where there was no fringe) estimated visually in metres; type of shoreline habitat; species to which the nearest waterbird (hereinafter the nearest neighbour) belonged. Two thou- sand, four hundred, and fifty-three duck events were sampled in

October, 1851 in February, and 1401 in March.

The following behavioural categories were included: feeding

(for subcategories see Green 1998 a ); sleeping (resting behaviour with head on back and eyes open or closed; moving birds were in- cluded in this posture); loafing (resting without head on back); comfort (preening, bathing, wing flapping, wing shivering, leg shaking, stretching, yawning, head shaking, bill dipping); swim- ming ; flying ; courtship (see Cramp and Simmons 1977 for dis- plays); aggression (intra- and inter-specific interactions); other

(alert, walking, drinking). Shoreline habitat types were Phragmites communis ; Typha angustifolia ; Scirpus spp. / Juncus spp. (including

J. acutus , J. maritimus , S. holoschoenus , S. maritimus ); Carex sp.;

Salicornia europea ; open shores (sand, mud, or rocks). The avail- able length of shoreline types and area of open water less than and more than 10 m from the shoreline was calculated from a habitat map.

At FAO, flock scans were conducted at 20-min intervals on 15,

20, and 21 November 1995. Owing to the relatively small number of teal present, we only consider data on individual behaviour ( n =

417 duck events).

Pairing data

The proportion of teal paired at SBG was estimated in February and March. The pair status of teal is relatively difficult to assess

(cf. Hepp and Hair 1983; Amat 1990) because the sexes are diffi- cult to distinguish and pairs show low levels of aggression to conspecifics. Pair status therefore could not be assessed during flock scans. Between scans, individuals seen moving were selected for continuous focal sampling and monitored for up to 5 min to see if they were spatially associated with a particular conspecific. All equivocal cases were deleted from the sample. In March, compara- tive data were collected for Mallards, Anas platyrhynchos , and

Green-winged Teal, Anas crecca .

Statistical analyses

To construct diurnal time–activity budgets, behaviour was first expressed as the mean percentage of birds engaged in behaviour of a particular category each hour (to weight scans by the number of individuals observed). Separate budgets were constructed for each month. Flock-scan data have problems of non-independence. The

Green and El Hamzaoui

Fig. 2. Diurnal rhythms of Marbled Teal ( Marmaronetta angustirostris ) at Sidi Bou Ghaba in October ( a ), February ( b ), and March ( c ) (“06” represents 06:00–06:59, etc.). “Locomotion” includes swimming and flying and “resting” includes sleeping and loafing.

behaviour and position of different teal at any moment partly de- pends on that of conspecifics in the same flock. The positions of birds at 30-min intervals are also interrelated. Thus, we used con- servative methods to analyse patterns of behaviour and habitat use.

When analysing activity, we summed all data from each flock scan

(individuals switched activities repeatedly within 30 min) and con- centrated on dominant behaviours recorded in every scan. When analysing habitat selection, we summed all data for each day (since individuals often remained in the same position for several hours).

In analyses of variance involving distance to shoreline, D , data

2115 were ln ( D + 1)-transformed and we used Newman–Keuls post hoc tests.

Results

At SBG, 100.4 ± 5.5 teal (mean ± SE) were recorded per flock scan ( n = 25 scans) in October 1997, 68.6 ± 32.9 ( n =

27) in February 1995, and 48.3 ± 2.0 ( n = 29) in March

1995. Peak counts were 266 in October, 105 in February, and 62 in March. At FAO in November 1995, 9.3 ± 0.7 teal were recorded per scan ( n = 45, peak count = 19).

Pairing

A small number of teal were paired by October, although no precise data were collected. From 15 to 23 February, 5%

( n = 20, 95% confidence intervals on proportion (CI) = 0–

25%) of teal were paired. From 17 to 21 March, 35% of teal

( n = 249, CI = 29–41%), 76% of Mallards ( n = 132, CI =

68–83%), and 64% of Green-winged Teal ( n = 84, CI = 53–

74%) were paired.

As pairing progressed from October to March, teal showed a decreasing spatial association with conspecifics. In

October, 92% of nearest neighbours recorded ( n = 2543) were conspecifics when teal constituted 7% of the water- birds at SBG. In February, 68% of nearest neighbours ( n =

1691) were conspecifics when 3% of waterbirds were teal.

In March, 32% of nearest neighbours ( n = 1372) were con- specifics when 4% of waterbirds were teal.

Time–activity budgets

Diurnal time–activity budgets varied between months

(Table 1, Fig. 2). After October, very little feeding was ob- served (Table 1). Feeding was confined to crepuscular peri- ods (Fig. 2). Of 284 feeding events in October, 68% were upending, 30% were neck dipping, and 2% were bill dip- ping. In February and particularly March, locomotion (par- ticularly swimming) increased at the expense of resting, and courtship activity increased (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Habitat selection

Distance to the shoreline

Teal strongly selected wetland margins and avoided cen- tral, open-water areas. The area available less than 10 m to the shoreline represented only 26% of the total area at SBG in 1995 and 31% in 1997, yet it was used by 77% of teal scanned in February, 89% in March, and 82% in October.

On all 15 study days, the proportion of birds observed using this boundary area was higher than that expected at random

(sign test, P < 0.0001).

Analysis of variance showed that the distance of each teal to the water’s edge depended on its behaviour (sleeping, loafing, swimming, or comfort, F

[3,240] month ( F

[2,240]

= 14.6, P < 0.0001),

= 37.4, P < 0.0001), and the interaction be- tween the two ( F

[6,240]

= 5.3, P < 0.0001). Post hoc tests showed that in March and October, swimming teal were far- ther from shore than those engaged in other behaviours. In

March, loafing teal were farther from shore than those that were sleeping.

2116 Can. J. Zool. Vol. 78, 2000

Fig. 3. Diurnal association with different shoreline types at Sidi Bou Ghaba in different months (observed use) relative to availability

(expected use). The data were weighted for different times of the day by calculating the percent association with each habitat type dur- ing each 1-h period, then taking the mean and SE (shown by error bars).

Selection of shoreline type

Associations with shoreline habitats showed major sea- sonal differences (Fig. 3). In February and March, teal showed an association with T. angustifolia on all 13 study days (sign test, P < 0.0001). In October, teal strongly se- lected open shores and made more use of P. communis habi- tats (Fig. 3). Selection of shoreline type by birds coming out of the water was more pronounced. In February–March,

87% of birds coming out of the water ( n = 454) were in

T. angustifolia and only 9% were on open shores. In Octo- ber, all birds ( n = 1005) were on open shores. These differ- ences were associated with a switch (from B to C; see

Fig. 1) in the SBG section, where teal were concentrated, between 1995 and 1997.

In March (but not in other months), association with edge habitats covaried with behaviour type (χ 2 test on the number of scans in which each behaviour–habitat combination was recorded, χ 2

19

= 29.72, P < 0.001). Sleeping teal were those most strongly associated with T. angustifolia . Feeding teal were associated with flooded S. europa (Fisher’s exact test,

P < 0.02). No S. europa habitat was available in October, when 44% of feeding birds were associated with open shores and 34% with T. angustifolia .

Discussion

As is typical in ducks of the subfamily Anatinae, Marbled

Teal breed in their first year (Cramp and Simmons 1977).

Our study shows that although some teal are paired in Octo- ber, most individuals pair in March or later, shortly before breeding. This is later than most dabbling ducks but similar to other Aythyini (Cramp and Simmons 1977; Hepp and

Hair 1983; Baldassarre and Bolen 1994). In Spain, courtship and pairing are completed by some teal as late as May after they arrive at breeding sites (Navarro and Robledano 1995).

During the nonbreeding period, teal are mainly nocturnal foragers. In midwinter, almost no foraging was recorded during the day, while feeding continued after dawn and be- fore dusk in early and late winter, when nights were shorter; this is a common pattern in migratory ducks in winter

(Paulus 1988; Michot et al. 1994; Green et al. 1999 b ). We found no evidence to support speculation (Livezey 1996) that teal are more crepuscular and less nocturnal than Aythya species. Thus, the idea that there has been an evolutionary shift from crepuscular to nocturnal activity in the Aythyini

(Livezey 1996) is not supported.

Throughout the annual cycle, the feeding behaviour of

Marbled Teal is typical of Anatini (Green 1998 a ), and this is the only extant member of the Aythyini with no propensity to dive. At SBG, both diurnal and nocturnal feeding were concentrated in section C (Fig. 1), and teal showed a prefer- ence for feeding in S. europa when it was available; faecal analysis showed that they fed on adult chironomids and

S. europa seeds in February (Green 2000).

The tendency for teal to spend more time in locomotory activities as the nonbreeding period progressed from October to March may be linked to increased courtship activity, i.e., more time spent swimming in search of potential partners and courtship opportunities. However, the most important reason for locomotion appeared to be the need for escape be- haviour in response to overhead flights of female Marsh

Harriers, Circus aeruginosus , and Hen Harriers, Circus cyaneus . In response to these overhead passes the teal invari- ably flew a short distance out on to open water, then swam slowly back to the shoreline habitats. The relative frequency of harrier flights increased between October and March.

Green and El Hamzaoui

Harriers have a similar effect on the behaviour of other win- tering ducks (Tamisier 1974; Euliss and Harris 1987), and such predator activity may help explain nocturnal foraging in teal (McNeil et al. 1992; Tamisier and Dehorter 1999).

Marbled Teal are associated with microhabitats along the shoreline and with emergent vegetation at SBG, FAO, and other nonbreeding and breeding sites (Green 1998 b ). At

SBG, teal were closer to the shore, on average, than were other wintering ducks except Gadwall, Anas strepera (Green

2000). However, microhabitat use at SBG also covaried with behaviour, swimming birds making the most use of open water (partly in response to harrier flights). Studies of inter- specific differences in habitat use have often failed to take into account the influence of behaviour (e.g., White and

James 1978; Nudds et al. 1994, but see Heimsath et al.

1993), making results difficult to interpret (because differ- ences in diel rhythms may lead to changes in apparent habi- tat use when there are no real differences in selection of, for example, foraging or roosting habitat).

The selection of T. angustifolia shoreline habitats in the central, permanent part of SBG in February and March 1995 contrasted with the selection of open shores in the southern, temporary area in October 1997. This switch may have been related to changes in water level or flock size, as the water was higher and more teal were present in October. Deeper water and a larger flock size may reduce the predation risk

(Pöysä 1987; Gauthier-Clerc et al. 1998).

In spite of the classification of the Marbled Teal within the Aythyini, this study illustrates how its foraging ecology is more typical of the Anatini. In terms of winter ecology, the Marbled Teal only resembles Aythya species in its late pairing. For some reason (e.g., because low levels of intra- specific aggression permit access to food for unpaired birds), early pairing of teal may not bring the benefit of improved late-winter body condition observed in many Anatini

(Tamisier et al. 1995).

The results of our study illustrate the importance of con- serving a diversity of shallow, margin habitats in wetlands important to nonbreeding Marbled Teal. Such habitats re- quire protection from human disturbance (which prevents the teal from using the eastern margin of section B at SBG) and overgrazing or reed-cutting (which are widespread prob- lems at Moroccan and Spanish wetlands; Green 1993; Dakki and El Hamzaoui 1997). Particular attention is also required to locate and manage appropriately those areas that are im- portant for nocturnal foraging, which may be little used dur- ing the day (McNeil et al. 1992).

Acknowledgements

The fieldwork was financed by the Consejería de Medio

Ambiente, Junta de Andalucía, and the Centre National de la

Recherche Forestière. We are grateful to D. Gonzalez, A. El

Hamzaoui, and S. Roberts for assistance in data collection and to M. Maghnouj for help in planning and arranging per- mits. J.A. Amat, T.C. Michot, W.A. Montevecchi, A.

Tamisier, and an anonymous reviewer commented on earlier drafts. Thanks are also extended to M.L. Chacón, J.J. Chans,

M. Ferrer, H. Garrido, F. Hiraldo, D. and K. Hoffmann, R.

Pintos, Comite des Programmes de la Conservation de la

2117

Nature (Rabat, Morocco), and The Wildfowl and Wetlands

Trust (Slimbridge, U.K.).

References

Altmann, J. 1974. Observational study of behaviour: sampling methods.

Behaviour, 49 : 227–267.

Amat, J.A. 1984. Ecological segregation between Red-crested

Pochard Netta rufina and Pochard Aythya ferina in a fluctuating environment. Ardea, 72 : 229–233.

Amat, J.A. 1990. Age-related pair bonding by male Eurasian Wigeons in relation to courtship activity. Auk, 107 : 197–198.

Baldassarre, G.A., and Bolen, E.G. 1994. Waterfowl ecology and management. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Cramp, S., and Simmons, K.E.L. 1977. Handbook of the birds of

Europe, Middle East and North Africa. Vol. 1. Oxford Univer- sity Press, Oxford.

Dakki, M., and El Hamzaoui, M. 1997. Rapport national sur les zones humides (Maroc). MedWet report, Administration des Eaux et

Forêts et de la Conservatión des Sols, Rabat, Morocco.

Euliss, N.H., and Harris, S.W. 1987. Feeding ecology of Northern

Pintails and Green-winged Teal wintering in California. J. Wildl.

Manag. 51 : 724–732.

Gauthier-Clerc, M., Tamisier, A., and Cezilly, F. 1998. Sleep– vigilance trade-off in Green-winged Teals ( Anas crecca crecca ).

Can. J. Zool. 76 : 2214–2218.

Green, A.J. 1993. The status and conservation of the Marbled Teal

Marmaronetta angustirostris . IWRB Spec. Publ. No. 23, Interna- tional Waterfowl and Wetlands Research Bureau, Slimbridge, U.K.

Green, A.J. 1998 a . Comparative feeding behaviour and niche orga- nization in a Mediterranean duck community. Can. J. Zool. 76 :

500–507.

Green, A.J. 1998 b . Habitat selection by the Marbled Teal Marma- ronetta angustirostris , Ferruginous Duck Aythya nyroca and other ducks in the Göksu Delta, Turkey in late summer. Rev.

Ecol. Terre Vie, 53 : 225–243.

Green, A.J. 1998 c . Clutch size, brood size and brood emergence in the Marbled Teal Marmaronetta angustirostris in the Marismas del Guadalquivir, southwest Spain. Ibis, 140 : 670–675.

Green, A.J. 2000. The habitat requirements of the Marbled Teal

( Marmaronetta angustirostris

Ménétr.): a review.

In Limnology and aquatic birds: monitoring, modelling and management

Proceedings of the 2nd Societas Internationalis Limnologiae In- ternational Congress, Yucatán, Mérida, Mexico. Edited by F.A.

Comín, J.A. Herrera, and J. Ramírez. pp. 131–140.

Green, A.J., and Navarro, J.D. 1997. National censuses of the Mar- bled Teal, Marmaronetta angustirostris , in Spain. Bird Study,

44 : 80–87.

Green, A.J. Navarro, J.D., Dolz, J.C., and Aragoneses, J. 1999 a .

Brood emergence patterns in a Mediterranean duck community.

Bird Study, 46 : 116–118.

Green, A.J., Fox, A.D., Hughes, B., and Hilton, G.M. 1999 b . Time– activity budgets and site selection of White-headed Ducks

( Oxyura leucocephala ) at Burdur Lake, Turkey in late winter.

Bird Study, 46 : 62–73.

Heimsath, S.F., Lopez de Casenave, J., Cueto, V.R., and Cittadino,

E.A. 1993. Uso de habitat en Fulica armillata , Fulica leuco- ptera y Gallinula chloropus durante la primavera. Hornero, 13 :

286–289.

Hepp, G.R., and Hair, J.D. 1983. Reproductive behavior and pair- ing chronology in wintering dabbling ducks. Wilson Bull. 95 :

675–682.

Hughes, R.H., and Hughes, J.S. 1992. A directory of African wetlands. International Union for the Conservation of Nature

2118 and Natural Resources, Gland, Switzerland, Cambridge, U.K., and Nairobi, Kenya, United Nations Environment Programme,

Cambridge, U.K., and World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

Livezey, B.C. 1986. A phylogenetic analysis of recent anseriform genera using morphological characters. Auk, 103 : 737–754.

Livezey, B.C. 1991. A phylogenetic analysis and classification of recent dabbling ducks (tribe Anatini) based on comparative mor- phology. Auk, 108 : 471–507.

Livezey, B.C. 1996. A phylogenetic analysis of modern pochards

(Anatidae: Aythyini). Auk, 113 : 74–93.

McNeil, R., Drapeau, P., and Goss-Custard, J.D. 1992. The occur- rence and adaptive significance of nocturnal habits in waterfowl.

Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 67 : 381–419.

Michot, T.C., Moser, E.B., and Norling, W. 1994. Effects of weather and tides on feeding and flock positions of wintering

Redheads in Chandeleur Sound, Louisiana. Hydrobiologia,

279/280 : 263–278.

Morgan, N.C. 1982. An ecological survey of standing waters in

North West Africa: III. Site descriptions for Morocco. Biol.

Conserv. 24 : 161–182.

Navarro, J.D., and Robledano, F. ( Coordinators ). 1995. La Cerceta

Pardilla Marmaronetta angustirostris en España. Instituto Nacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza – Ministero de Agricultura,

Pesca y Alimentación (ICONA-MAPA) Colección Técnica, Instituto

Nacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza, Madrid, Spain.

Nudds, T.D. 1983. Variation in richness, evenness and diversity in diving and dabbling duck guilds in prairie pothole habitats. Can.

J. Zool. 61 : 1547–1550.

Nudds, T.D. 1992. Patterns in breeding waterfowl communities. In

Ecology and management of breeding waterfowl. Edited by

B.D.J. Batt, A.D. Afton, M.G. Anderson, C.D. Ankney, D.H.

Johnson, J.A. Kadlec, and G.L. Krapu. University of Minnesota

Press, Minneapolis and London. pp. 540–567.

Can. J. Zool. Vol. 78, 2000

Nudds, T.D., and Wickett, R.G. 1994. Body size and seasonal co- existence of North American dabbling ducks. Can. J. Zool. 72 :

779–782.

Nudds, T.D., Sjöberg, K., and Lundberg, P. 1994. Ecomorpho- logical relationships between Palearctic dabbling ducks on Bal- tic coastal wetlands and a comparison with the Nearctic. Oikos,

69 : 295–303.

Oring, L.W., and Sayler, R.D. 1992. The mating systems of water- fowl. In Ecology and management of breeding waterfowl.

Edited by B.D.J. Batt, A.D. Afton, M.G. Anderson, C.D.

Ankney, D.H. Johnson, J.A. Kadlec, and G.L. Krapu. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis and London. pp. 190–213.

Paulus, S.L. 1988. Time–activity budgets of nonbreeding Anatidae: a review. In Waterfowl in winter. Edited by M.W. Weller. Uni- versity of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. pp. 135–152.

Pöysä, H. 1987. Feeding–vigilance trade-off in the teal ( Anas crec- ca ): effects of feeding method and predation risk. Behaviour,

103 : 108–122.

Tamisier, A. 1974. Etho-ecological studies of Teal wintering in the

Camargue (Rhone Delta, France). Wildfowl, 25 : 123–133.

Tamisier, A., and Dehorter, O. 1999. Camargue, canards et foulques : fonctionnement et devenir d’un prestigieux quartier d’hiver. Centre Ornithologique du Gard, Nîmes, France.

Tamisier, A., Allouche, L., Aubry, F., and Dehorter, O. 1995. Win- tering strategies and breeding success: hypothesis for a trade-off in some waterfowl species. Wildfowl, 25 : 123–133.

Thévenot, M. 1976. Les oiseaux de la réserve de Sidi-Bou-Rhaba.

Bull. Inst. Sci. Rabat, 1 : 67–99.

White, D.H., and James, D. 1978. Differential use of fresh water environments by wintering waterfowl of coastal Texas. Wilson

Bull. 90 : 99–111.