t19e

advertisement

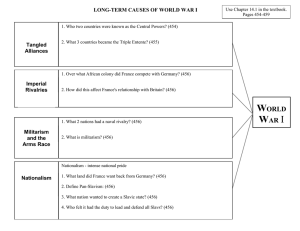

Topic 19 European Nationalism Objectives Knowledge 1. To know nationalism as a feeling and an identity of individuals. 2. To understand the impact of nationalism on European politics. Skills 1. To infer the underlying meaning of written text. 2. To compare maps and identify similarities and differences. Attitude 1. To appreciate and respect own and others’ culture. 2. To treasure our learning opportunities. 3. To have empathy Teaching Flow Items 1. Format Teaching Objectives Content Question to ponder A question & brief introduction To let students have a clear How did nationalism learning focus affect European politics from the late 19th to the early 20th century? To let student analyze the What is nationalism? meaning and promotion of nationalism 2. Task 1 and To know more (1) to (3) Data based question 3. Task 2 Data based question To let students analyze the impact of nationalism on a country through national anthems How was nationalism promoted by national anthems? 4. Task 3 and To know more (4) Data based question To let students analyze the impact of nationalism on Europe What impacts did nationalism have on European politics? 5. Conclusion Summary chart To summarize the main points of this topic Meaning and impact of nationalism 1 Question to ponder How did nationalism affect the European politics from the late 19th to the early 20th century? Task 1: What is Nationalism? Study Source A to find out what nationalism was. Source A The following adapted from The Last Lesson written by Alphonse Daudet. M. Hamel said: “My children, the order has come from Berlin to teach only German in the schools of Alsace and Lorraine. The new master comes tomorrow. This is your last French lesson. I want you to be very attentive.” My last French lesson! While I was thinking of all this, I heard my name called. It was my turn to recite. But I got mixed up on the first words and stood there, and not daring to look up. M. Hamel said to me: 2 “I won’t scold you, little Franz; you must feel bad enough. You pretend to be Frenchmen, and yet you can neither speak nor write your own language?’ M. Hamel went on saying that French was the most beautiful language in the world -- the clearest, the most logical; that we must guard it among us and never forget it. Then he opened a grammar book and read us our lesson. I had never listened so carefully. After the grammar, we had a lesson in writing. That day M. Hamel had new copies for us, written in a beautiful round hand: France, Alsace, France, Alsace. All at once the church-clock struck twelve. “My friends,” said M. Hamel, “I--I --” He could not go on. Then he turned to the blackboard, and wrote as large as he could: “Vive La France!”# Then he stopped and leaned his head against the wall, and made a gesture to us with his hand; “School is dismissed--you may go.” #‘Vive La France’ means ‘Long Live France’. ** For those students interested in this story, go to Extended Task (1) to read the full version. Source: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10577/10577-8.txt) Topic 19 European Nationalism Answer the following questions with reference to Source A. 1. Which subject was this last lesson for? Suggested answer: French (grammar and writing) 2. What feeling was promoted by the teacher during this last lesson? Explain your answer. Suggested answer: Nationalism - love for their language: French as the most beautiful language in the world – the clearest and most logical; must guard it - love for their country: France, Alsace; Long Live France - sense of unity: Frenchmen must know how to read and write French 3 a. Who were the ‘new masters’? Suggested answer: Germans. b. What do you think the writer would feel about ‘the new masters’? Explain your answer. Suggested answer: Free answer, e.g. He would hate the new masters, because these foreigners occupied his territory (Alsace and Lorraine) and did not allow them to learn French in school. To know more (1) Background of The Last Lesson The Last Lesson took place in a French school in Alsace and Lorraine. Alsace and Lorraine are located today in France, on the border with Germany. There have always been a mixture of French and German speakers living here. In 1870, France and Prussia, the strongest German state, had the Franco-Prussian War during the process of German unification. France was defeated and Alsace and Lorraine was ceded to Germany. German replaced French in school. 3 To know more (2) Nationalism as emotion Nationalism was an emotional subject, involving individual identity, and it became a factor in European politics throughout the nineteenth century, leading to the First World War. In the Middle Ages, personal allegiance would have been owed to the church, the kings and the lords. By the Renaissance, the emergence of the vernacular meant that some kings would have identified with their subjects through the written vernacular. In this connection, any sense of the nation would have been closely defined by allegiance to the kings. By the Enlightenment, when it was thought that kings ruled by virtue of a social contract, they were thought of as 4 representing the state. By the 19th century, the increasing focus on common language and culture as the foundation of the state meant that nationalism came to be closely tied to the emotion. A nation’s people would have felt deeply about the state and its interests, especially insofar as its sovereignty was threatened. This is brought about in the story, “The last lesson,” written by French author Alphonse Daudet. To know more (3) Popular education and the rise of nationalism Nationalism was also promoted by popular education. Throughout the 16th to the 18th centuries in Western Europe, there were more and more schools, especially primary schools. By the 19th century, many schools were supported by the government and they taught in the national language. The spread of primary education promoted the national language, the national history and the national literature. They were very important in inculcating the national identity. Topic 19 European Nationalism Task 2: How was nationalism promoted by national anthem? National anthem is another symbol of a nation and teaching it is another way to promote nationalism. Study Source B to find out the feeling and action promoted among the French people. Source B The following is the French national anthem, La Marseillaise. La Marseillaise was written in 1792 during the French Revolution, by which the French overthrew the king and confirmed that sovereignty should reside in the nation. The audio file of it is available from http://www.marseillaise.org/english/ (click ‘audio’). Let us go, children of the fatherland Our day of Glory has arrived. Against us stands tyranny, The bloody flag is raised, The bloody flag is raised. Do you hear in the countryside The roar of these savage soldiers They come right into our arms To cut the throats of your sons, your country. Answer the following questions with reference to Source B. 1. Who are ‘children of the fatherland’? Suggested answer: The French (‘fatherland’ refers to France) 2. What problems did they face? Explain your answer. Suggested answer: - The tyrant was bad for the people. (against us stands tyranny) - The savage soldiers killed the people and weakened the country. (‘cut the throats of your sons, your country’) - (Other reasonable answers are acceptable.) 3. If you were the ‘children of the fatherland’, what should you do to deal with the problems, according to the national anthem? Explain your answer. Suggested answer: I should fight against tyrant and his soldiers. Clues: let us go, our day of Glory has arrived (need to strengthen the country); bloody flag raised (use violence) 5 4. Did the promotion of nationalism bring about benefits or harm to a country? Explain your answer. (This is a challenging question. Hint: refer to Sources A-B or using your own knowledge.) Suggested answer: Free answer, e.g. - Benefits: increasing a sense of unity and willing to work together to protect their country (Source B), and work hard to strengthen their country (own knowledge) - OR Harm: strengthen a country by war leading to poorer relationship with other countries (e.g. Source A), and casualties (own knowledge) OR Both harm and benefits Task 3: What impacts did nationalism have on European politics? Other than in France, nationalism also rapidly spread in Europe and had strong influence on different European countries. Study Sources C and D and find out how nationalism affected the Austrian Empire. Source C Source D 6 2 1 The Austrian Empire Europe today Source: Department of History, Chinese University of Hong Kong Note for Source C: 1. The Austrian Empire 2. German Confederation controlled by Austria in 1815-1866 Topic 19 European Nationalism To know more (4) The Austrian Empire The Austrian Empire set up in 1804 consisted of the Habsburg lands of Austria and other places such as Bohemia and Hungary. It became the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867-1918 after its defeat in the Austro-Prussian War, and broke up into Austria and different states in 1919 after its defeat in the First World War. Answer the following questions with reference to Sources C and D. 1. Compare Sources C and D and identify the countries today that were formerly controlled by the Austrian Empire. Suggested answer: Germany, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2. Do you think the people in Austria and the countries you identified in question (1) supported or opposed the breakup of the Austrian Empire? Why did they have such a view? Suggested answer: Countries Supported/opposed Reasons Austria Opposed Did not want to reduce their influence Countries identified in question(1) Supported Austria and these countries belong to different nations; now they could be free from Austria’s control and form their own country 3. Would the breakup of the Austrian Empire promote peace or create conflicts in Europe? Explain your answer. (Hint: refer to Sources C, D and use your own knowledge about the meaning and impact of nationalism.) Suggested answer: Free answer, e.g. - Peace: respect for nationalism, so avoiding conflicts and revenge e.g. new states were created, such as Czechoslovakia and Hungary (Source D) - OR Conflict: new states may want to have expansion and so more international conflicts (Source A); new states were too weak to protect themselves and so other countries may attack them (own knowledge) - OR Both peace and conflicts 2. 根據資料 I,梁啓超認為甚麼因素才是改革成功的關鍵?中國又是否具備該些 因素?解釋你的答案。 7 Conclusion: Nationalism was emotional. By the nineteenth century, it became part of the personal identity of a lot of people. It became generally accepted that people who spoke the same language, had the same culture and belonged to the same nation. However, if the people of the same nation were allowed to create their own country, some of the old empires might break up. The resultant changes could be politically dangerous. Extended activity (1): Read the full version of the story: The Last Lesson THE LAST LESSON BY ALPHONSE DAUDET 8 I started for school very late that morning and was in great dread of a scolding, especially because M. Hamel had said that he would question us on participles, and I did not know the first word about them. For a moment I thought of running away and spending the day out of doors. It was so warm, so bright! The birds were chirping at the edge of the woods; and in the open field back of the saw-mill the Prussian soldiers were drilling. It was all much more tempting than the rule for participles, but I had the strength to resist, and hurried off to school. When I passed the town hall there was a crowd in front of the bulletin-board. For the last two years all our bad news had come from there--the lost battles, the draft, the orders of the commanding officer--and I thought to myself, without stopping: “What can be the matter now?” Then, as I hurried by as fast as I could go, the blacksmith, Wachter, who was there, with his apprentice, reading the bulletin, called after me: “Don’t go so fast, bub; you’ll get to your school in plenty of time!” I thought he was making fun of me, and reached M. Hamel’s little garden all out of breath. Usually, when school began, there was a great bustle, which could be heard out in the street, the opening and closing of desks, lessons repeated in unison, very loud, with our hands over our ears to understand better, and the teacher's great ruler rapping on the table. But now it was all so still! I had counted on the commotion to get to my desk without being seen; but, of course, that day everything had to be as quiet as Sunday morning. Through the window I saw my classmates, already in their places, and M. Hamel walking up and down with his terrible iron ruler under his arm. I had to open the door and go in before everybody. You can imagine how I blushed and how frightened I was. Topic 19 European Nationalism But nothing happened, M. Hamel saw me and said very kindly: “Go to your place quickly, little Franz. We were beginning without you.” I jumped over the bench and sat down at my desk. Not till then, when I had got a little over my fright, did I see that our teacher had on his beautiful green coat, his frilled shirt, and the little black silk cap, all embroidered, that he never wore except on inspection and prize days. Besides, the whole school seemed so strange and solemn. But the thing that surprised me most was to see, on the back benches that were always empty, the village people sitting quietly like ourselves; old Hauser, with his three-cornered hat, the former mayor, the former postmaster, and several others besides. Everybody looked sad; and Hauser had brought an old primer, thumbed at the edges, and he held it open on his knees with his great spectacles lying across the pages. While I was wondering about it all, M. Hamel mounted his chair, and, in the same grave and gentle tone which he had used to me, said: “My children, this is the last lesson I shall give you. The order has come from Berlin to teach only German in the schools of Alsace and Lorraine. The new master comes to-morrow. This is your last French lesson. I want you to be very attentive.” What a thunder-clap these words were to me! Oh, the wretches; that was what they had put up at the town-hall! My last French lesson! Why, I hardly knew how to write! I should never learn any more! I must stop there, then! Oh, how sorry I was for not learning my lessons, for seeking birds' eggs, or going sliding on the Saar! My books, that had seemed such a nuisance a while ago, so heavy to carry, my grammar, and my history of the saints, were old friends now that I couldn’t give up. And M. Hamel, too; the idea that he was going away, that I should never see him again, made me forget all about his ruler and how cranky he was. Poor man! It was in honor of this last lesson that he had put on his fine Sunday-clothes, and now I understood why the old men of the village were sitting there in the back of the room. It was because they were sorry, too, that they had not gone to school more. It was their way of thanking our master for his forty years of faithful service and of showing their respect for the country that was theirs no more. While I was thinking of all this, I heard my name called. It was my turn to recite. What would I not have given to be able to say that dreadful rule for the participle all through, very loud and clear, and without one mistake? But I got mixed up on the first words and stood there, holding on to my desk, my heart beating, and not daring to look up. I heard M. Hamel say to me: 9 “I won’t scold you, little Franz; you must feel bad enough. See how it is! Every day we have said to ourselves: ‘Bah! I’ve plenty of time. I’ll learn it tomorrow.’ And now you see where we've come out. Ah, that’s the great trouble with Alsace; she puts off learning till tomorrow. Now those fellows out there will have the right to say to you: ‘How is it; you pretend to be Frenchmen, and yet you can neither speak nor write your own language?’ But you are not the worst, poor little Franz. We’ve all a great deal to reproach ourselves with. “Your parents were not anxious enough to have you learn. They preferred to put you to work on a farm or at the mills, so as to have a little more money. And I? I’ve been to blame also. Have I not often sent you to water my flowers instead of learning your lessons? And when I wanted to go fishing, did I not just give you a holiday?” Then, from one thing to another, M. Hamel went on to talk of the French language, saying that it was the most beautiful language in the world -- the clearest, the most logical; that we must guard it among us and never forget it, because when a people are 10 enslaved, as long as they hold fast to their language it is as if they had the key to their prison. Then he opened a grammar book and read us our lesson. I was amazed to see how well I understood it. All he said seemed so easy, so easy! I think, too, that I had never listened so carefully, and that he had never explained everything with so much patience. It seemed almost as if the poor man wanted to give us all he knew before going away, and to put it all into our heads at one stroke. After the grammar, we had a lesson in writing. That day M. Hamel had new copies for us, written in a beautiful round hand: France, Alsace, France, Alsace. They looked like little flags floating everywhere in the school-room, hung from the rod at the top of our desks. You ought to have seen how every one set to work, and how quiet it was! The only sound was the scratching of the pens over the paper. Once some beetles flew in; but nobody paid any attention to them, not even the littlest ones, who worked right on tracing their fishhooks, as if that was French, too. On the roof the pigeons cooed very low, and I thought to myself: “Will they make them sing in German, even the pigeons?” Whenever I looked up from my writing I saw M. Hamel sitting motionless in his chair and gazing first at one thing, then at another, as if he wanted to fix in his mind just how everything looked in that little school-room. Fancy! For forty years he had been there in the same place, with his garden outside the window and his class in front of him, just like that. Only the desks and benches had been worn smooth; the walnut-trees in the garden were taller, and the hop-vine, that he had planted himself twined about the windows to the roof. How it must have broken his heart to leave it all, poor man; to hear his sister moving about in the room above, packing their trunks! For they must leave the country next day. Topic 19 European Nationalism But he had the courage to hear every lesson to the very last. After the writing, we had a lesson in history, and then the babies chanted their ba, be, bi, bo, bu. Down there at the back of the room old Hauser had put on his spectacles and, holding his primer in both hands, spelled the letters with them. You could see that he, too, was crying; his voice trembled with emotion, and it was so funny to hear him that we all wanted to laugh and cry. Ah, how well I remember it, that last lesson! All at once the church-clock struck twelve. Then the Angelus. At the same moment the trumpets of the Prussians, returning from drill, sounded under our windows. M. Hamel stood up, very pale, in his chair. I never saw him look so tall. “My friends,” said he, “I--I --” But something choked him. He could not go on. Then he turned to the blackboard, took a piece of chalk, and, bearing on with all his might, he wrote as large as he could: “Vive La France!” Then he stopped and leaned his head against the wall, and, without a word, he made a gesture to us with his hand; “School is dismissed--you may go.” 11 Source: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10577/10577-8.txt Extended activity (2) A comparison can be made between the national anthem of France and that of China, and between the methods to promote nationalism used by the European countries and the HKSAR government. Summary Chart Definition: a feeling of loyalty and an identity of a group of people united by race, language, history Methods to promote nationalism 19th century - ceremonies European - symbolic art nationalism - interpretation of history - education and promotion of a common culture - socio-economic or diplomatic achievements Impact 12 - wars and expansion for nation building - breakup of old empires and rise of new states - arms race and economic competition

![“The Progress of invention is really a threat [to monarchy]. Whenever](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005328855_1-dcf2226918c1b7efad661cb19485529d-300x300.png)