Eyre

advertisement

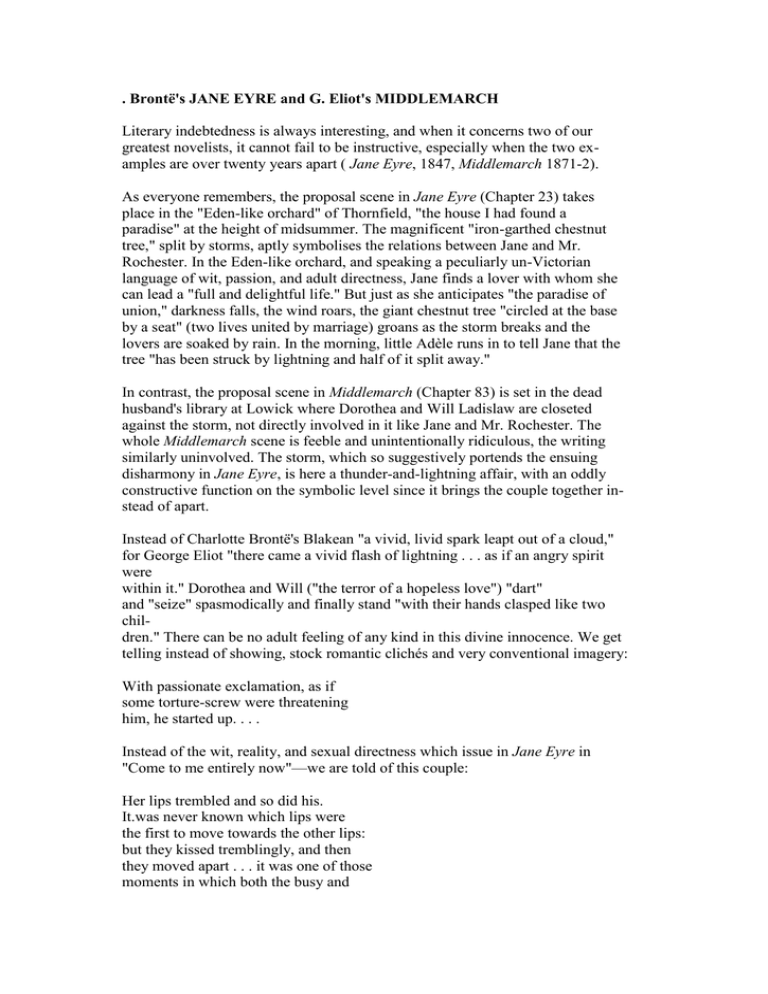

. Brontë's JANE EYRE and G. Eliot's MIDDLEMARCH Literary indebtedness is always interesting, and when it concerns two of our greatest novelists, it cannot fail to be instructive, especially when the two examples are over twenty years apart ( Jane Eyre, 1847, Middlemarch 1871-2). As everyone remembers, the proposal scene in Jane Eyre (Chapter 23) takes place in the "Eden-like orchard" of Thornfield, "the house I had found a paradise" at the height of midsummer. The magnificent "iron-garthed chestnut tree," split by storms, aptly symbolises the relations between Jane and Mr. Rochester. In the Eden-like orchard, and speaking a peculiarly un-Victorian language of wit, passion, and adult directness, Jane finds a lover with whom she can lead a "full and delightful life." But just as she anticipates "the paradise of union," darkness falls, the wind roars, the giant chestnut tree "circled at the base by a seat" (two lives united by marriage) groans as the storm breaks and the lovers are soaked by rain. In the morning, little Adèle runs in to tell Jane that the tree "has been struck by lightning and half of it split away." In contrast, the proposal scene in Middlemarch (Chapter 83) is set in the dead husband's library at Lowick where Dorothea and Will Ladislaw are closeted against the storm, not directly involved in it like Jane and Mr. Rochester. The whole Middlemarch scene is feeble and unintentionally ridiculous, the writing similarly uninvolved. The storm, which so suggestively portends the ensuing disharmony in Jane Eyre, is here a thunder-and-lightning affair, with an oddly constructive function on the symbolic level since it brings the couple together instead of apart. Instead of Charlotte Brontë's Blakean "a vivid, livid spark leapt out of a cloud," for George Eliot "there came a vivid flash of lightning . . . as if an angry spirit were within it." Dorothea and Will ("the terror of a hopeless love") "dart" and "seize" spasmodically and finally stand "with their hands clasped like two children." There can be no adult feeling of any kind in this divine innocence. We get telling instead of showing, stock romantic clichés and very conventional imagery: With passionate exclamation, as if some torture-screw were threatening him, he started up. . . . Instead of the wit, reality, and sexual directness which issue in Jane Eyre in "Come to me entirely now"—we are told of this couple: Her lips trembled and so did his. It.was never known which lips were the first to move towards the other lips: but they kissed tremblingly, and then they moved apart . . . it was one of those moments in which both the busy and the idle pause with a certain awe. Their lips take on an autonomous life and become animate objects moving in a void. No wonder the Gods become so inattentive that they forget to keep their -10record books up to date ("It was never known . . ."). We are even instructed how to respond: "With a certain awe." The forced insistences ("with passionate ex clamation," "he burst out"); the violently heroic rhetoric ("battling with his anger," "fatal as a murder"); the inappropriate Shakespearean reminiscences ("it is throwing back my love for you as if it were a trifle"); Ladislaw's coyly arch femininities ("I could not offer myself to any woman"); all issue in an uninten tional bathos ("stretching his hand automatically towards his hat"). Realising vaguely that the genuinely masculine presence that Charlotte Brontë achieves by a triumphant effort of creative will-power for Mr. Rochester (in the proposal scene at least, where it matters most) is here inappropriate, George Eliot makes Dorothea propose herself—with Lucy Snowe's "My heart will break" ( Villette, Chapter 41). And instead of the restrained density and vivid fragments of poetic life which Charlotte Brontë offers there, we get Dorothea "rising from her seat, the flood of her young passion bearing down all the obstructions which had kept her silent—the great tears rising and falling in an instant: 'I don't mind about poverty—I hate my wealth.'" It is hard then to doubt that without Jane Eyre and Villette, which we know George Eliot read and admired ("Still more wonderful than Jane Eyre . . . there is something almost preternatural in its power"), the proposal scene in Middle march would, at the very least, have been different. It is the use of a great piece of literary creation by a writer who has read ...