Lecture: Documents, texts, works

advertisement

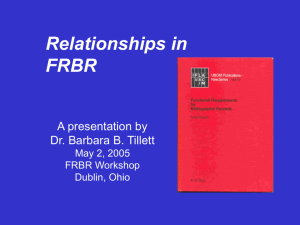

Information in the form of recorded intellectual creation Documents, texts, works The universe of informative artifacts Sometimes known as the bibliographic universe. Most limited definition: written texts. Limited definition: recorded intellectual creation. Expansive definition: any object designated as informative. Slide 2 What kinds of entities populate the bibliographic universe? Compare these statements: •I went to the MOMA in New York and saw Van Gogh’s Starry Night. •I also saw a screening of Rosemary’s Baby there. What is the difference between Starry Night and Rosemary’s Baby? Slide 3 What kinds of entities populate the bibliographic universe? Compare these statements: • Afterwards I went to the Strand bookstore and bought a cheap used paperback for the plane, Murder at the Savoy, in the Martin Beck series. • Apparently the Swedish title of that book is Police, Police, Mashed Potatoes. • The Laughing Policeman is an excellent title in that series. • The Kindle version has some typos, so you might get a printed copy instead. Slide 4 What kinds of entities populate the bibliographic universe? When I talk of Starry Night, I mean a specific, unique item. When I talk of Murder at the Savoy, I may mean a specific, unique item (the copy I just purchased), or I might mean a specific version but not necessarily a unique physical item (in Swedish the title that means “Police, police, mashed potatoes”), or I might mean just Murder at the Savoy in all its potential variations. Slide 5 Documents, texts, and works The terms work, text, and document help us to distinguish between these different uses of Murder at the Savoy. •The copy I bought at the Strand is a document, an individual item. •The sequence of words and symbols that is contained within the copy I bought at the Strand is the text. Other copies have the same text. Other formats, such as a Kindle version, may also have the same text. •All the different potential sequences of words and symbols—all the versions, or texts—constitute the work. Slide 6 Documents, texts, and works The artistic work Starry Night is represented by a single text, a single document. The work Murder at the Savoy, on the other hand, has a number of texts and many documents (copies). When we say Murder at the Savoy, sometimes we mean the whole set of potential variations (the work) and sometimes we mean something more specific. Slide 7 The indeterminacy of the work Like the notion of the species in biology, it is often difficult to say where one work ends and another begins. In fact, compared to works, the species is an orderly concept, even with its multiple potential definitions. People have come up with different rules of thumb for distinguishing between works: for example, in the FRBR model, a strict translation is not a new work, but a loose translation is. Unfortunately, there is little agreement about these rules; for other people, any translation should be a new work. Slide 8 Are these the same work? • Video footage of a warehouse on fire, shot by a bystander with a cell phone, by a news crew with a camera, and by the security camera of a neighboring establishment. • A tweet and the tweet retweeted by another user. • The song La Bamba performed by Ritchie Valens (studio version) by Los Lobos (studio version) by Los Lobos (live, bootleg tape). Slide 9 Are these the same work? • A blog post that comments on a linked Web page; the same blog post when the linked page changes its text; the same blog post when the link becomes dead. • The Aiken-Rhett house in Charleston, as completed in 1818, and as it is today, “conserved and stabilized.” • The Russell house in Charleston, as completed in 1808 and as it is today, “gracefully restored.” Slide 10 Are these the same work? • The Huffington Post today, the Huffington Post one week ago, the Huffington Post one hour ago. • The arcade version of Pong, the home version of Pong, and a current Web version. • The currently operational version of World of Warcraft, as played for one hour, the World of Warcraft system without any players. Slide 11 The indeterminacy of documents Compared to the work, the idea of a document seems easy to understand. Buckland shows some difficulties here. Objects can be treated as informative, as evidence of some assertion, even if they were not created for that purpose, or even if they were not created by people at all. Slide 12 Are these documents at all? • Briet’s antelope in a field, Briet’s antelope in a zoo, Briet’s antelope dead and stuffed in someone’s house over the mantel, Briet’s antelope preserved as a biological specimen. • The chair you are sitting in; an Eames lounge chair in the showroom at Design Within Reach; an Eames lounge chair in the MOMA. • A lecture like this one, even if it’s not recorded. Slide 13 Who the hell cares? My brain hurts! Does it matter whether an antelope is a document or whether the Swedish version of Murder at the Savoy is a different work from the English version? Two groups care a lot: textual scholars and information scientists (er, documentalists? us.). Slide 14 Textual studies and bibliography Textual scholars attempt to map, describe, and compare all the versions (texts) of a work. Think of Shakespeare’s plays: there are so many different versions, even from Shakespeare’s lifetime (quartos, folio, etc). And printers make so many errors! How can we interpret Shakespeare’s plays with confidence if we do not have the correct “text of the work”? Slide 15 The work as an ideal version For some textual scholars, the work is understood as “the correct version” of a set of texts. (There is some similarity here to the Linnean idea of basing a species definition off an ideal specimen.) However, the work as conceived in this way may have never actually existed as an embodied text. This idea of the work focused around an author’s perceived intentions as obtained through a variety of evidence. Slide 16 The work as an ideal version This sense of the work has fallen out of favor: •Authorial intention is less often used as the basis of interpretation. •Changes made by editors and publishers are less likely to be seen as “mistakes.” Slide 17 Products of textual scholarship Textual scholars’ research may take these forms: •Analytical bibliography/descriptive bibliography. •Textual criticism and critical editions. Slide 18 Information science/studies/documentation/librarian ship/etc Information scholars and professionals try to determine how best to “collect, preserve, organize, represent, select, reproduce, and disseminate” (in Buckland’s words)…what? What are the units we are working with? Documents? (Does one ever want an antelope?) Works? Texts? It depends? Sometimes one wants a specific copy of Hamlet, sometimes one wants any of a certain subset (in English), sometimes one just wants…Hamlet. Slide 19 Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) FRBR is an entity-relationship model to describe the bibliographic universe, developed by the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) as a conceptual model for library catalogs. One goal of the FRBR model is to show relationships between entities. (Wouldn’t it be great to show how all the things that might be considered Hamlet are related?) Slide 20 FRBR entity-relationship model FRBR entities include works, expressions, manifestations, and items. Chart from Tillet, 2004 Slide 21 FRBR works A work in the FRBR model is “a distinct intellectual or artistic creation.” FRBR examples of works: • All editions of an anatomy textbook are one work. • A Bach organ fugue and an arrangement for chamber orchestra are the same work. • A French movie in its original form and a version with English subtitles (and one dubbed into Japanese) are the same work. Slide 22 FRBR expressions An expression in FRBR is analagous to a text: “the intellectual or artistic realization of a work” in a form, be it textual, sound, image, musical notation, whatever. The expression encompasses the intellectual but not the physical form (e.g., typeface and layout are not part of the expression). Examples of expressions: • The score and performances of a quintet. • A German text and its English translation. Slide 23 FRBR manifestations A manifestation in FRBR is the realization of an expression in a physical medium. The same expression can be embodied in different manifestations. All copies that are produced as part of the same set are the same manifestation. Examples of manifestations: • The same performance of a musical work on CD and on LP (two manifestations, one expression). • The same edition of a newspaper in print and in microform (two manifestations, one expression). Slide 24 FRBR items An item in FRBR refers to the actual physical copy of a manifestation. Examples of items: • A particular autographed copy of a book. • A particular copy of a musical score in which one page is missing. Slide 25 User tasks for FRBR entities The FRBR report identifies four tasks that users should be able to accomplish with all the entities: • Find. • Identify. • Select. • Obtain. Slide 26 Attributes and entities in FRBR Each entity has a different set of attributes. Some attributes are similar: works and expressions both have titles. (The title of a work, under which expressions are grouped, might be Hamlet, but the title of a particular expression might be William Shakespeare’s Hamlet.) Some attributes are completely different. Manifestations have publishers. Works don’t. Slide 27 Interlude: library catalogs • UT catalog (traditional). • Worldcat (some clustering of versions; uses existing standard records). • Australian Literature Resource, Austlit (implements some FRBR goals, but not with current cataloging record structure or rules). Slide 28 Limitations of FRBR: computer game case study McDonough and colleagues try to map versions of the computer game Adventure to the entities in the FRBR model. The difficulties that they encounter seem relevant to the use of FRBR in organizing any digital artifacts: • Many versions with different underlying code may exist for a single version of the user experience. • The experience of a digital artifact depends to a variable extent on the software and hardware infrastructure in which it is embedded. What constitutes the game? Slide 29 Documents or information? Is it different to think of a universe of information as opposed to a universe of documents, texts, and works? When you search the Web, are you searching for documents or “information”? In what situations is it useful to consider documentary structures and in what situations is it useful to consider “information” unbound? Can—should—information be unbound? Slide 30