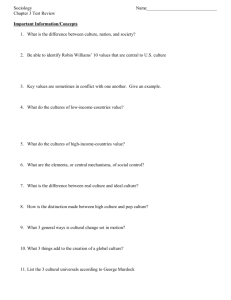

What is language?-1st lecture( History)

advertisement

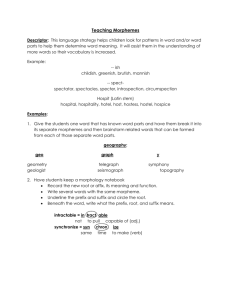

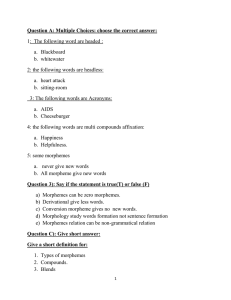

Lecture 1 What is language? language distinguishes humankind from the rest of the animal world. Other animals, communicate with one another, or at any rate stimulate one another to action, by means of cries. Many birds utter warning calls at the approach of danger; some animals have mating-calls; apes utter different cries to express anger, fear or pleasure. Some animals use other modes of communication: many have postures that signify submission, to prevent an attack by a rival; hive-bees indicate the direction and distance of honey from the hive by means of the famous bee-dance; dolphins seem to have a communication system which uses both sounds and bodily posture. But these various means of communication differ in important ways from human language. Animals’ cries are not articulate. This means, basically, that they lack structure. They lack, for example, the kind of structure given by the contrast between vowels and consonants, and the kind of structure that enables us to divide a human utterance into words. We can change an utterance by replacing one word by another: a sentry can say ‘Tanks approaching from the north’, or he can change one word and say "Aircraft approaching from the north’ or ‘Tanks approaching from the west’; but a bird has a single indivisible alarm-cry, which means 'Danger!’ This is why the number of signals that an animal can make is very limited: the Great Tit has about thirty different calls, whereas in human language the number of possible utterances is infinite. It also explains why animal cries are very general in meaning. These differences will become clearer if we consider some of the characteristics of human language. What is language? A human language is a signalling system. The written language is secondary and derivative. In the history of each individual, speech or signing is learned before writing, and there is good reason for believing that the same was true in the history of the species. There are communities that have speech without writing, but we know of no human community which has a written language without a spoken or signed one. System in language A language consists of a number of linked systems, and structure can be seen in it at all levels. For a start, any language selects a small number of vocal sounds out of all those which human beings are able to make, and uses them as its building blocks, and the selection is different for every language. The number of vocal sounds that a human being can learn to make (and to distinguish between) is quite large – certainly running into hundreds – and if you know a foreign language you will also be familiar with speech sounds which do not occur in English, like the vowel of the French word feu or the consonant of the German ich. Pronunciation varies from speaker to speaker. Speakers from Texas, from Manchester, from Edinburgh, from New York use different sounds. Doesn’t this mean, therefore, that there are hundreds of different sounds in English? This is obviously true. These variations, moreover, occur between different social groups as well as between different regions, for there are class accents as well as regional accents. Morphology: words and morphemes System is also found in the way words are constructed from smaller parts. Words are often defined as minimum free forms, i.e. the smallest pieces of language which can by themselves constitute a complete utterance. But they are not the smallest meaningful pieces of language: in the words refill and slowly we know perfectly well what re- and -ly mean, but these do not constitute words. The smallest meaningful element in a language is called a morpheme. So re- and fill are both morphemes. The former cannot exist except when joined to other morphemes, and so is a bound morpheme; but fill is also a word, and is therefore a free morpheme. A word may consist of one morpheme or of many: the word unthoughtful consists of three morphemes, whereas the word molecule is only one; and the word I is a single morpheme which is itself composed of a single phoneme. Lexical words and grammatical words English words fall into a number of different grammatical categories– what were traditionally called ‘the parts of speech’, but which are now usually called wordclasses. Obvious examples of word-classes are nouns (such as brother, idea, library), adjectives (such as new, beautiful, young), verbs (such as come, annihilate, fraternize) and pronouns (such as you, I, who, anybody). Lexical sets System is also found in the realm of meaning. Words tend to form sets, and the meaning of a word depends on the other words in the set, with which it can be contrasted. This is very clear in sets of words denoting such things as military ranks (captain, major, colonel, etc.), where the meaning of each term depends on its position in the hierarchy. In the sets of words for family relationships, the categories are different in different languages. These categories also change with time, so that the Middle English word nevew (from which Modern English nephew develops) can refer to a nephew or a grandson. Another obvious set is formed by words for colours , where different languages divide up the spectrum differently: for example, in Russian there is no single word corresponding to our blue, but two words, (a) siniy (roughly ‘dark blue’) and (b) goluboy (roughly ‘light blue’). Language is symbolic In all these ways a language shows system, and it is now perhaps clear, at any rate in a general way, what we mean when we say that a language is a system of vocal sounds. These sounds are symbolic. That is, they stand for something other than themselves, and their relationship to the thing that they stand for is not a necessary one, but arbitrary. There are a very few words which relate in a non- arbitrary way to the thing to which they refer. For instance, the word cuckoo refers to a bird whose call sounds somewhat like the word itself. Similarly, the word quack, referring to the call of a duck, is an approximation to the noise that ducks actually make. The vast majority of words, however, are purely symbolic, with no necessary relationship between the word or its sounds and the referent of the word. Thus English uses the word cow to refer to a large, domesticated bovine animal, while French refers to the same animal as avache: neither word sounds like the animal in question, or relates to it in any other way, and the fact that these two language have very different words for the same animal demonstrates that the relationship between the word and its referent is essentially arbitrary. The functions of language Language is used for more than one purpose. The person who hits their thumb with a hammer and utters a string of curses is using language for an expressive purpose: they are relieving their feelings, and need no audience but themselves. People can often be heard playing with language: children especially like using language as if it were a toy, repeating, distorting, inventing, punning and jingling. There is also a play element in the use of language in some literature. But when philosophers use language to clarify their ideas on a subject, they are using it as an instrument of thought. When two neighbours gossip over the fence, or exchange conventional greetings as they pass one another in the street, language is being used to strengthen the bonds of cohesion between the members of a society. Language, it seems, is a multipurpose instrument. One function, however, is basic: language enables us to influence one another's behavior , and to influence it in great detail, and thereby makes human cooperation possible. Other animals co-operate, for example many primates, and social insects like bees and ants, and use communication systems in the process. But human co-operation is more detailed and more diversified than that found elsewhere in the animal kingdom. This human cooperation would be unthinkable without language, and it is obviously this function which has made language so successful and so important; other functions can be looked on as by-products. A language, of course, always belongs to a group of people, not to an individual. The group that uses any given language is called the speech community. Language types A human language, then, is a signalling system which operates with symbolic vocal sounds, and which is used by some group of people for the purposes of communication and social co-operation. There are over six thousand human languages spoken in the world today, which all fall under this definition of language, but nevertheless differ widely from one another. Various attempts have been made, therefore, to classify languages into different types. One scheme distinguishes two main types of language, the analytic and the synthetic. An analytic language is one that uses very few bound morphemes, such as are seen in English prefixes and suffixes (refill, slowly) and in the inflections (grammatical endings) of English nouns and verbs (boxes, talking, talked). Chinese, for example, is a highly analytic language: it has few bound forms, its words being mostly one-syllable morphemes or compounds of free morphemes. A synthetic language, by contrast, uses large numbers of bound morphemes, and often combines long strings of them to form a single word. Examples of highly synthetic languages are the Inuit languages and Turkish. Most languages lie between these extremes, for the synthetic–analytic division is not a sharp one: rather it is a continuous scale, a continuum, with languages occupying various points between the two extremes. Its weakness as a system of classification is that languages are mixed: some are more synthetic or more analytic in some respects, some in others. It nevertheless has its uses: it makes sense, for example, to say that the English language in the course of its history has become less synthetic and more analytic. Another well-known classification divides languages into four types: isolating, agglutinative, flectional (or inflectional) and polysynthetic (or incorporating). Language universals The study of language types has been closely linked to the search for language universals, that is, features which all languages possess, and must possess. Typology examines language variation, while the study of universals tries to establish the permissible limits of this variation, and both use the same kind of material. The search for linguistic universals was given considerable impetus by the work of Noam Chomsky. Because of the ease with which children learn language, Chomsky maintains that human language is innate: in the brain is a genetically transmitted ‘language organ’, which determines the syntactic and semantic properties of all languages. In Chomsky’s view, therefore, all languages have the same underlying structure, and it should be possible to demonstrate the existence of universals. Not all specialists in the field, however, believe that all language universals are innate: some take the view that some universals may have psychological or functional explanations. Some proposed universals are absolute, for example that all languages have vowels. It can be added that all languages have oral vowels (but not all languages have nasal vowels). There are also strong tendencies which are not quite universals: for example, nearly all languages have nasal consonants, but there are just a few that lack them. Some proposed universals are of the ‘If A, then B’ type: for example, ‘If a language has V–S–O as its basic word-order, then it invariably has prepositions.’ On the other hand, if a language has S–O–V as its basic word-order, then it will probably have postpositions; but this is not a universal, but a strong tendency, because there are counter-examples: Classical Latin, for example, has S–O–V as its basic word-order, but has prepositions. Universals of the ‘If A, then B’ type are called implicational universals; and tendencies of this type are similarly called implicational.