PNI

advertisement

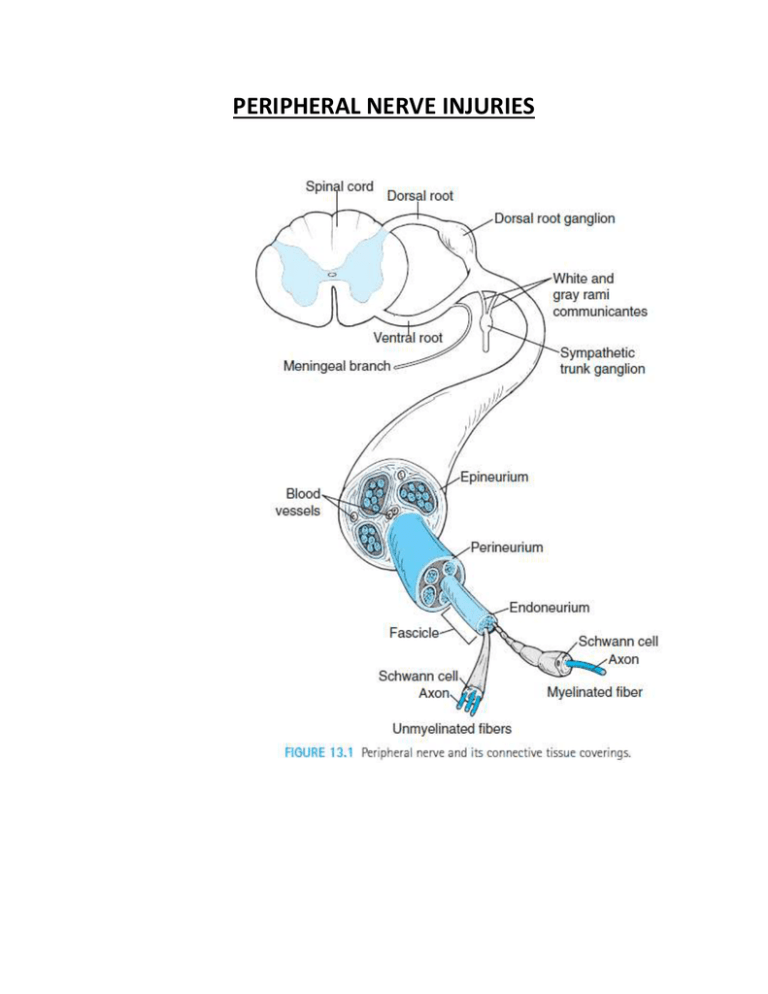

PERIPHERAL NERVE INJURIES Brachial Plexus The brachial plexus is formed by the anterior primary divisions of the C5-T1 nerve roots (Fig.13.3). The plexus functions as the distribution center for organizing the contents of each peripheral nerve. Upper plexus injuries (C5,6): The most common injury to the plexus involves compression or tearing of the upper trunk. The mechanism involves shoulder depression and lateral flexion of the neck to the opposite side. There is loss of abduction and lateral rotation of the shoulder and weakness in elbow flexion and forearm supination (waiter’s tip position). Erb’s palsy occurs with birth injuries when the shoulder is stretched downward, although Benjamin5 cautioned that there are maternal and infant factors that could contribute this injury in addition to the applied forces during delivery. A “stinger” occurs with injuries as might occur when playing football and the individual lands on the upper torso and shoulder with the head/neck laterally flexed in the opposite direction. Middle plexus injuries (C7): Rarely seen alone. Lower plexus injuries (C8,T1): Usually due to compression by a cervical rib or stretching the arm overhead. Klumpke’s paralysis (paralysis of the intrinsics of the hand) occurs in birth injuries when the baby presents with its arm overhead.5 Complete or total injury of the plexus: Complete paralysis from a total brachial plexus injury may occur as a complication of birth; it is known as Erb-Klumpke’s paralysis and is associated with Horner’s syndrome in one-third of those severely affected.5 NERVE INJURY AND RECOVERY (1) First degree injury (neuropraxia): minimal structural disruption—complete recovery; (2) second degree (axonotmesis): complete axonal disruption with wallerian degeneration—usually complete recovery; (3) third degree (may be either axonotmesis or neurotmesis)—disruption of axon, and endoneurium poor prognosis without surgery; (4) fourth degree (neurotmesis): disruption of axon, endoneurium, and perineurium— poor prognosis without surgery; (5) fifth degree (neurotmesis) complete structural disruption—poor prognosis without microsurgery. Recovery of Nerve Injuries Nature and level of injury. The more damage to the nerve and tissues, the more tissue reaction and scarring occur. Also, the proximal aspect of a nerve has greater combinations of motor, sensory and sympathetic fibers, so disruption there results in a greater chance of mismatching the fibers, thus affecting regeneration. Regeneration is often said to occur at a rate of 1 inch per day, but rates from 0.5 to 9.0 mm per day have been reported based on the nature and severity of the injury, duration of denervation, condition of the tissues, and whether surgery is required. Timing and technique of repair. Laceration or crush injuries that disrupt the integrity of the entire nerve require surgical repair. Timing of the repair is critical, as is the skill of the surgeon and technique used to align the segments accurately and avoid tension at the suture line for optimal nerve regeneration. Different regenerative potential outcomes following nerve repair have also been reported based on groupings of specific nerves. • Excellent regenerative potential: radial, musculocutaneous, and femoral nerves • Moderate regenerative potential: median, ulnar, and tibial nerves • Poor regenerative potential: peroneal nerve Age and motivation of the patient. The nervous system must adapt and relearn use of the pathways once regeneration occurs. Motivation and age play a role in this, especially in the very young and the elderly.