Document 15335877

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004

** Draft paper — not to be cited **

Gender and the Global Textile Industry, 1650-2000

Janet Hunter (LSE) and Helen Macnaughtan (SOAS)

Gendered Workforce Composition

It is strongly emphasized in a number of the national overviews that there was no such thing as a common textile worker experience even within a single national or regional entity. Rather, a diversity of forms of production, workforce composition and economic and commercial environments combined to produce a range of historical experiences across time and space. Some of the most fundamental divisions within and between workforce were related to the use of male and/or female workers, and constructions of gender impacted on, and were influenced by, the coexistence of and competition between different forms of production and the industry’s response to the economic imperatives that it faced. Commercialisation and industrialisation, often association with the gradual growth of wage labour and movement of textile production away from the household, had significant implications for the gender identity of textile work, but this process was far from being always the same in different countries and regions.

The importance over time of the textile industry globally has meant that employment in textiles has at certain periods, particularly before and during the course of a nation’s industrialisation, accounted for a significant share of the national labour force. For example, in the mid-nineteenth century, an estimated 10% of the

Japanese population worked in textile production, while in the early 1930s some 50% of the industrial workforce in Shanghai was employed by the textile industry. In

1950s Lower Austria and in Uruguay, 16-17% of all industrial workers were in textile production. While the significance of the textile industry’s workforce cannot be denied, what is of interest to this paper is the gender composition of that workforce and the differences and similarities in gender aspects of textile work. The paper will also consider the extent to which the gendering of textile work embraced characteristics that are more widely found in the history of manufacturing as a whole.

The textile industry has generally been viewed as an industry suitable for the employment of female workers. In part this has been due to the tradition of textile production (particularly spinning) as “women’s work” in the pre-industrial household economy, and later its classification as a light (rather than heavy) manufacturing industry (prior to advanced mechanisation and the rise of synthetic textile production), and therefore seen as suitable for the “nimble hands” of female workers. We also find widespread the view held by textile producers that women workers were both a more

‘docile’ and ‘cheaper’ alternative to male employment and were readily available as an expendable and/or untapped labour pool. In Japan, for example, primarily young females outnumbered males in the industrial workforce up until the 1930s because of the large numbers of ‘daughters’ released from the agricultural household into the growing textile industry, while in the 1960s the industry turned to the employment of

‘housewives’ as an unused labour force within the constraints of a rapidly expanding

Japanese economy and growing labour shortage. The gendered nature of textile employment overall is certainly a theme that emerges from many of the national overviews in this study.

1

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004

However, statistical data on the gender composition of textile employment in the past is often difficult to unearth, particularly when considering the pre-industrial industry. The same can be said for the availability of data providing a further breakdown by age and marital status. Eberling et.al.

’s paper on Germany notes that, although overall data is lacking, it can be assumed that women and girls formed the majority of labour in pre-industrial spinning, while the Netherlands paper on the preindustrial industry notes that the practice of only registering household heads in official records results in an under-registration of married women and children working in textile production. This is an important point when considering the gender composition of the textile workforce over time, as females may well have been unrecorded or un-represented in historical sources on textile employment due to their very gender as ‘female’ within a history centred around patriarchy.

1 Even in post-

WWII Japan, with its vigorous recording of industry data and compiling of industry histories, data on women workers (particularly ‘older’ married women) is often un(der)-recorded especially when they are viewed as temporary or supplementary workers.

It is fair to say that, in many of the countries represented in this study, female workers constituted at the very least a significant presence and at the most a vast majority in the textile workforce. Estimates suggest that 51-92% spinners in the 16-

18 th

century Netherlands were female, and up to 80% textile workers in 18 th

century

Lower Austria. Female workers dominated in the industrialised textile workforces of

Europe and in the USA, Japan and Argentina. Table 1 depicts the female proportion of textile employment in a number of countries in the 19 th -20 th centuries, gathered from data cited in some of the national overview papers. However, while most of the authors mentioned significant proportions of female employment textile production, there were some notable exceptions. Textile mills in nineteenth century Mexico were comprised of mainly male workers, (though women did work in smaller workshops as seamstresses) and it was not until US companies set up textile plants during the 1960s that female workers were utilised as a main workforce in Mexico. In India through to the 1920s handloom weavers were primarily male, and it was males who tended to migrate to work in the cotton mills that developed from the second half of the 10 th century. The development of wage labour during the 20 th

century defeminised textile work, and it was only right at the end of the century, with the setting up of new spinning mills in semi-rural areas, that this process began to some extent to be reversed. The presence of women on the factory floor was often determined by social constructions of gender over time in any one nation, and whether women were

‘permitted’ to work in large numbers outside of the home.

The composition of the textile workforce by gender was also determined by the industry’s position within the national (and global) economy over time. A core male workforce often predominated when the industry was commercialised in preindustrial economies, while mass production under industrialisation appeared to give way to ‘cheaper’ and ‘easily sourced’ female and young labour. In many industrialising nations the ‘model’ employment structure when setting up modern textile mills appeared to be one which employed small numbers of male technical staff and large numbers of female factory operatives. It would be fair to suggest that during and following the process of industrialisation, a significant majority of textile factory operatives around the world were characterised as female, young, and initially

1 For general problems in measuring the historical problems of women’s work see eg. B.Hill, ‘Women,

Work and the Census: a Problem for Historians of Women’, History Workshop 35, Spring, 1993.

2

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 of rural origin. Many of the countries under consideration were characterised in the pre-modern period by a process of rural industrialisation (in some cases ‘protoindustrialisation’). Women became increasingly dominant in Lower Austrian textile districts in the 18 th

century as producers felt the full weight of British competition.

That pattern was replicated not just in Austria at a much later date, but in a range of countries through the 18 th -19 th centuries. The US rayon industry in the first half of the

20 th

century followed this strategy, as did Indian textile producers in the 1980s.

The gendered aspects of production varied according to the region and the mode of production. An urban-rural distinction, originating in pre-industrial production, led to male dominance of artisanal production and female dominance in much rural production. This distinction continued to manifest itself in certain respects throughout the period up to the present, and is discussed below. In particular, the ongoing attempts by textile producers in many countries to turn to rural areas for their labour supply was premised on the assumption that rural labour was cheaper than urban, and that rural women were even cheaper. In some cases this pursuit of cheap rural female labour was associated with relocation. In others it brought temporary or permanent migration of workers from rural areas, or the persistence of subcontracting and putting out, and home-based production, such as in the Turkey and Uruguay of the 20 th

century. This process has only slowly undermined regional distinctions, but it has certainly influenced regional patterns of production, and acted as a driving force in the development of textile production overall across a large number of very diverse producing countries.

The gendered nature of the workforce was also determined by the economic position of the industry and any decline in that position. Curtailment of production or economic downturn has meant the industry could be staffed by older women (and men) as was the case in England during WWII. Globalisation in the late twentieth century has again produced a phenomena of a core female workforce, seen as cheap and easily laid-off when textile production loses its glow, as witnessed in 1960s

Mexico and 1990s Austria. This notion of female labour being ‘supplementary’ to core male labour is a notion that has continued over time, even in an industry such as textiles which has historically had a larger share of female workers than other

(manufacturing) industries. This often leads to the female composition of the textile workforce being considered ‘supplementary’ and ‘temporary’ as was the case in the nineteenth and twentieth century Japanese industry, or ending up as ‘informal’ or on the ‘periphery’ as in the textile piecework sector of 1970s Uruguay. This begs the question of how gender inherently shaped characteristics of the textile labour force over time and how much power the textile labour force was able to wield throughout history as determined by its gendered make-up.

Pre-Industrial, Rural-Artisan Distinction

It is apparent that textiles have a long history of production in most economies, and that both men and women were closely involved in textile production in the preindustrial period. However, the gender division of labour in pre-modern textile production showed considerable variation across countries, in conjunction with varying constructions of the gender identity of particular aspects of textile work. In pre-colonial and colonial Argentina, and among the indigenous producers in Mexico, weaving was identified as women’s work. In colonial America women were involved in all stages of the production process. More widespread appears to have been the identification of spinning as a mainly female occupation, and weaving as a

3

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 predominantly male occupation, a pattern that characterised not merely much of premodern Europe, but also Egypt, India and the non-indigenous producers in Mexico.

A major feature of most of these patterns of pre-industrial production is the dominance of the household as the production unit and the frequent coexistence of both domestic and artisanal production. Both these features had significant gender implications. First, since in most households it was a male who was the family head, that hierarchy tended to be reflected in the family’s organisation of production.

Secondly, the specialist artisans who often produced the highest value-added textiles, and the apprentices whom they trained, were invariably male, as demonstrated by the cases of Denmark and the Habsburg Empire in Europe, and further afield in both

India and Japan. Artisan textile production was in many cases controlled by guilds, which were again invariably restricted to males. Guilds and equivalent bodies therefore became in turn a form of gendering, helping to reinforce male dominance of certain areas of production. In Denmark and the Netherlands, as well as in Egypt and the Ottoman Empire, guilds were highly significant in controlling the male-dominated weaving industry. Whereas in both rural households and urban workshops the preindustrial male weaver was often referred to as a ‘master’ or ‘artisan’ (and had often undertaken an apprenticeship and/or was a member of a guild), this formal recognition of the male weaver (and his skill) was not something generally accorded to women. Spinning, carding and other processes performed by women were often seen as complementary to her other key tasks of household chores and child rearing.

These two features had particular implications for the gender division of labour within the industry. While female labour still formed a crucial part of household-based textile production, male labour was often dominant particularly in the case of weaving. Women were frequently excluded from the higher value-added end of textile production (often weaving), and, perhaps more importantly, from the status and training that was associated with it under the guild and apprenticeship system. While there is evidence that females were involved in the administration and marketing of textiles, and in Egypt, India and Japan, for example, a male artisan might work alongside other family members, there is also widespread evidence that female family members were under such circumstances frequently employed in subsidiary tasks (including spinning or winding). A common division of labour in the rural agricultural household appears to have been one where female labour dominated the spinning of yarn, male labour presided over the weaving of cloth, and both female and child labour performed preparatory and auxiliary tasks for male weavers. This

‘model’ of the central figure of male weaver as household head, supported by the labour of his wife and children was evident in seventeenth century Spain, seventeenth century Hapsburg monarchy, eighteenth century Denmark and in seventeenth and eighteenth century India.

Similar patterns of work can be identified within some areas of domestic production, where the male household head was the main textile worker, supported by other family members. However, in many, if not more cases, domestic production was mainly carried out by females, while the males of the household focussed on agricultural production. In pre-modern Brazil, for example, there was longstanding female involvement in textile production and trade in the home, and from Denmark and Spain in Western Europe, through the Ottoman Empire and Egypt as far as India and Japan, textile production was commonly undertaken as female by-employment within agricultural families. In Qing China the capitalist organisation of silk weaving employed males, while it was rural females who carried out cotton weaving in the context of the family economy. While we know that family economies had to

4

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 respond flexibly to changing imperatives, and that the internal division of labour did vary over time, the case of the Habsburg Empire suggests the existence of a sharper gender division of labour in artisanal households than in those of domestic producers.

The increased specialisation and division of labour associated with industrialisation was to take this gendering process further.

Family Based Production, and its Persistence into the 20 th

Century

A key feature of the process of commercialisation and mechanisation of textile production that has characterised the last 250 years is the persistence of existing ways of organising production, and frequently the coexistence of mechanised factory production with handicraft activity, often conducted within families. It is apparent that there was no simple linear relationship between handicraft and mechanised textile production, in which the former inevitably gave way to the latter. Even in Britain, the rapid growth of textile factories in both wool and cotton only gradually made inroads into the old handicraft practices, and a spectrum of organisational forms persisted, in which the family economy, and the household as a unit of production, retained considerable significance. This was even more the case in many other economies, and has persisted into the start of the 21 st

century. That persistence was supported by a range of factors, including the flexibility and adaptability of family economy strategies in many countries, an adaptability in which the women who often dominated domestic production invariably played a major role. In 19 th

century Brazil, for example, factory production of textiles began to emerge, but women’s participation in domestic textile production remained far greater than in any of the new mills.

A positive interaction between new and existing forms of production was often manifest early in the industrialisation process. Early mills in North America put out yarn to be woven by rural women, and rural putting out systems can be found not only in Qing China, but in 19 th

century Egypt, and in India and the Middle East through the 20 th

century. Handicraft weaving by both men and women was often given a new lease of life by the production of more even and higher quality machine spun thread. In addition, however, it became apparent that household and domestic production enjoyed continuing comparative advantages in many areas of textiles, and those families that demonstrated sufficient flexibility to exploit that comparative advantage could continue to play a significant role in the industry. In the Habsburg

Empire, and in Egypt, home-based women carried out labour intensive processes or those demanding specialist skills. Homeworking often expanded alongside the factory system, as unpaid or underpaid female family members offered seasonal and other flexibility, and a buffer labour force in times of depression or stagnation. As some forms of domestic production became less competitive in the face of factory or import competition, household producers turned to new areas of textile production, or those in which they continued to hold comparative advantage. Homeworking and sweatshops have been widespread in the garment industry in many European countries, and Egypt even developed a formal apprenticeship system for individual seamstresses.

The advantage of the family economy in the face of the growth of capitalist manufacturing production essentially lay not just in the flexibility of the response it offered, but in its ability to use unpaid labour, and the labour with the lowest opportunity cost at any particular point in time. Household strategies, particularly those of households in rural areas, invariably focussed on the collective earnings of the household, and not just the income of an individual member, and this strategy was

5

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 concerned to diversify sources of income (thus reducing risk), was willing to combine paid and unpaid labour, and also to contemplate the concept of ‘supplementary earnings’ for females. This priority is manifest not only in the Spain of the 18 th century, and 19 th

century Japan, but more recently in India, and even the Austria of the 1980s-1990s. Even in the context of the strengthening of the male breadwinner model that occurred in many industrialising economies in the 19 th -20 th centuries, the cases of the UK, the US and Japan demonstrate that collective family earnings often remained as important a consideration as the adult male wage. On balance, it seems that the persistence of family-based production and the family economy served to underline the significance of women in textile production even where mechanised production might be male-dominated.

Where the factory sector grew, the family, and hence the gender aspects of the family, also exercised a major influence on its operation. In the textile mills of late

19 th

and early 20 th

century Japan and China, for example, the family was a key player in the decision of an individual to take up employment, and here and elsewhere – for example in Uruguay, India and the Ottoman Empire - family connections were of persistent importance in both recruitment and work patterns. Through these means the dominance of the family, and the patriarchal relations that so often characterised it, became transposed to the factory, a process very evident from the experiences of the US, the UK and Japan. Gendered social hierarchies replicated themselves in the new workplaces, helping to establish an environment in which women were more likely to be identified as subordinate members of the workforce and those with domestic responsibilities were expected to perform them in addition to any paid or unpaid work. The burden of domestic responsibilities was particularly great where married women moved into wage work and employment outside the home, a feature not just of Western economies such as the UK and Denmark, but Asian economies such as China and Japan. Such tensions could lead to married female textile workers being regarded as less reliable, a situation that might lead to attempts to replace them with males or with short-term, unmarried females, or to employ them in less desirable tasks. A growing tendency in many countries in the 19 th century to associate women with ‘domesticity’, and to identify work outside the home with maleness served further to undermine many women’s position in paid work, and reinforce their familybased identity. Capitalist development in general tended to idealise the family, associating femininity with love and emotional bonds, and men with earning and with economic and power relationships. This shared ethos helped to shift the position of the family from a cooperative, flexible unit of production to a unit characterised by more rigid and hierarchical individual functions, and with, over time, a lesser economic role.

Production, technology and skill — feminising and masculinising the workforce

The process of (re)defining the labour force composition in the textile industry by gender can be thought of as a process of either feminisation or masculinisation. There are several reasons why these processes took hold in many of the countries studied, but technological change was an important part and was often accompanied by changes to the national economy within which the textile industry operated.

2 Not only the importance of the household and its gendered operation, but also the pre-industrial

2 For some interesting case studies see G.de Groot & M.Schrover, Women Workers and Technological

Change (1995), and L.Sommestad, ‘Gendering Work, Interpreting Gender: the Masculinization of

Dairy Work in Sweden, 1850-1950’, History Workshop 37, Spring, 1994.

6

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 gender division of textile labour had a significant impact on the gendering of the new mechanised forms of textile production. In terms of technological innovation, the industry was generally female dominated when the processes were very ‘simple’ and done by hand. With the advent of semi-automation in the proto-industrial and early industrialisation eras, masculinisation would occur as men took over many of the tasks, previously performed by women, using new technology. This would tend to reverse again once industrialisation advanced, as automation and mass production allowed for a (re)feminisation of the workforce to take place. Similarly, the position of the textile industry within the overall economy of a nation encouraged the same process. With commercialisation in the pre-industrial economy, adult males took over weaving from women in handicraft and became masters, artisans or a ‘labour aristocracy’ who were often well-paid and operating in exclusive guilds. However, under both mechanization and proletarianisation, particularly as mass production in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries designated textiles a labour-intensive, light manufacturing industry, factories moved from employing men to ‘de-skilled’, lowerwaged women and children.

There was never any simple relationship between technology change and the division of labour in textile production, and technology change was always part and parcel of the ongoing social construction of ‘male’ and ‘female’ jobs, but a number of general points may be made in relation to the gendering of technology and skill, and the consequent feminisation or masculinisation of jobs and sectors. Firstly, mechanisation has in many cases been associated with the feminisation of the workforce. In the case of China, for example, as the cotton and silk industries shifted to mechanised production, it was male jobs that were lost, and female jobs that were created. Nevertheless, in India it was the work that was done by females that was potentially more susceptible to mechanisation, suggesting that in this case it was female jobs that were likely to be lost. It is clear, however, that in many cases the introduction of new technology permitted cheaper female workers to replace more expensive male ones. The introduction of ring spinning in countries such as Japan, the UK and the US offered an opportunity to employ more unskilled females, while the introduction of powerlooms removed some of the requirements for skill and strength that had helped male weavers to retain their jobs. However, as the nature of jobs changed, and along with it the identity of those who performed them, those same tasks became recategorised in terms of ‘skill’ designation and pay. Mule spinning in the UK was undertaken by male workers. With spinning equipment that no longer required such skill or strength, nor the employment of a number of assistants, females could be employed, but the task came to be constructed as low skill, ‘female’ work.

Such changes were, however, often fiercely resisted. Technical change in the US Fall

River mills undermined male spinners’ authority as men supervising other adults, posing a challenge to their very identity as male workers in possession of some status.

The association of female labour with low skill, absence of qualifications and training, and low pay was not a new phenomenon associated exclusively with the development of mechanised production. As noted earlier, pre-modern apprenticeship was invariably associated with males, women were excluded from many tasks, and were often engaged in ‘supplementary’ processes in support of a core male worker.

At the same time, the evidence from Denmark suggests that some pre-industrial female textile workers were relatively skilled. Moreover, the advent of rapid technology change posed new challenges both to the organisation of textile production and to social norms and constructs of gender. Male and female workers in early factories in Japan and Argentina, for example, were often the subject of acute

7

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 complaints from employers concerning the general lack of discipline, their reluctance to engage in hard work, and their inclination for absenteeism. What is clear is that the process of technological change, whether imported or endogenous, had the capacity to change the relations of production and promote an increasing division of labour. In that process many scholars accept that a degree of ‘deskilling’ took place, in which both males and females suffered. We need to ask, however, how meaningful the concept of skill, and hence deskilling, is. In responding to this challenge, whether real or perceived, it was male workers who were normally able to arrogate to themselves the highest paid, highest status jobs. They were also able to reconstruct the notion of skill to identify it with masculinity. Skilled jobs were by definition those undertaken by males. If a female worker undertook a task, it could not be skilled work, since females were by definition untrained and unskilled. In times of crisis, it is suggested for the Netherlands, there may have been a process of male institutionalisation of inferior female jobs, but more visible has been the tendency within textile production everywhere for men to command the specialist skilled jobs such as engineer or foreman, and for women to take the burden of shopfloor production. The process of technology change in conjunction with an ongoing reconstruction of gender in the workplace therefore established the foundations for a less flexible gender division of labour and justifications for that division of labour that have continued to be articulated through to the present.

The emerging availability of alternative manufacturing jobs in an economy also ensured a feminisation of the textile industry, as men were more likely to into higher paid and heavy sectors of manufacturing. Women, on the other hand, often remained longer in the textile industry and were less likely to be employed in heavier manufacturing industries. On the flip side, when there were less alternatives to textile production or when jobs were scarce under economic downturn, male workers tended to remain or reclaim textile jobs from women. In such cases, they were often found to occupy a more powerful position in the process itself, ensure that the environment favoured them, and carry out a process of assigning better status to their jobs via titles like ‘master’ or through the formation of guilds and later unions. These were processes that were far more likely to happen under masculinisation than under feminisation. Similarly, as demonstrated by the case of Mexico, contraction and/or decline of the industry meant that textiles moved from being a booming industry comprising well paid, skilled and unionised male workers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to an industry of “unskilled, non-unionised and low-paid women workers” under globalisation. And in the USA, factories employed non-unionised black, Asian and Hispanic females under globalisation, displaying not only a feminisation but also a ‘race to the bottom’ construction of the workforce under economic pressure. A common reason for feminising the textile labour force was therefore economic and the inherent cost-effectiveness of female labour, with female wages classified as lower and ‘cheap’ by virtue of gender. This cost advantage encouraged textile employers to feminise the workforce in their factories. While the nature of the industry was deemed suitable for the employment of women, as

Seidman’s paper on Turkey points out: “such massive participation of women and girls in expanding sectors of textile production was no accident, nor was it because of nimble fingers. It was part of the process of lowering labour costs in the struggle for competitive survival”.

The notion of gender itself played a large role in shaping the process of either masculinisation or feminisation, and there were social and cultural reasons for gendering the textile workforce. We know from looking at the US and Brazil that

8

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 early factories separated their workers by gender, although in other countries, including Japan, women and men worked side by side in the first cotton mills.

However, the participation of men and women in a single industry was a sine qua non for the emergence of a gendered division of labour. The gendered division of labour interacted with the process of technology change to produce a division of labour between the sexes that was far from being equal, but which also, as Roy notes for

India, had the capacity to lead to an overall higher female work force participation rate. While pre-industrial household production was generally female-dominated or broadly divided between the sexes, entering employment in workshops or factories outside of the home was not deemed suitable work for women in some countries at certain points in history — e.g. China in the late Ming period and India prior to the

1970s. Another reason for feminisation of the textile workforce, was the seemingly inherent nature of being ‘female’. This can be demonstrated by the Shanghai mills in the 1920s who substituted strike-active male workers with female workers and the

USA mills in the 1860s who turned to Irish immigrant females because they would provide a more “docile” and “stable” labour force. In Brazil and India, few women were employed in early factories and, when they were, were segregated on the shopfloor in different areas from the male workers. In Egypt, males “fiercely opposed the entry of females to their workplace and some even physically attacked them”, while new factories (in this case the making of hats) were set up with female labour because they were seen as carrying on a ‘tradition’ of female work and therefore not “violating the established gender division of labour”. Over time, the social exclusion of women from some textile sectors was often legitimised, which allowed for a change in cultural and social norms and a feminisation, or at the very least ‘incorporation’ of females, within the industry’s workforce. In 1860s China, male lineages and local male elites influenced and legitimised the employment of girls in textile factories, while declarations from religious authorities in the Ottoman empire and foreign female ‘role models’ helped persuade girls to enter textile employment.

Thus, during the course of textile history there has been a continual process of negotiating and constructing ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ roles within the industry. In

Japan, as in Denmark and Egypt, for example, prevailing assumptions about what constituted men’s and women’s work were brought to the factory. However, new ways of organising production could also offer opportunities for changing the gendering of textile work. Beinin suggests that the growth of the new industries in

19 th

century Egypt had the capacity to change the gender division of labour, as symbolised by the tarbush (fez) industry with its female workforce. In the UK, by contrast, some workers sought to establish new trades as being in the artisan tradition, hence preserving them for males. The fact that in most pre-industrial economies women had engaged in some form of textile work did not necessarily mean that factories replicated existing divisions, although they often reflected them. The consequence was that the gendering of textile factory production during the 19 th

-20 th centuries varied according to country and region, and over time. In 19 th

century

Mexico, for example, textile production was seen as ‘male’, whereas the late 19 th century silk filatures that proliferated in Japan, China and the Ottoman Empire were worked almost entirely by young women. Within England, the cotton, woollen and worsted industries embraced very different workforces with very different gender compositions, while in China the gender division of labour varied from factory to factory depending on the nature of native place ties and the extent of the workers’ handicraft background. In textiles, however, there were very few sectors of production that did not involve both women and men, although there were some that

9

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 employed predominantly one sex or the other. In this respect textiles, through its employment of a large number of females, may not necessarily be representative of manufacturing as a whole. Nevertheless, in as far as the gendering of the work process within industries and within factories is concerned, the case of textile production is not necessarily so distinct from other industries.

Gender, Wages and the Workplace Environment

Gender played a key role in determining the level of skill and the level of payment in the majority of national textile industries. The same task or process, when transferred from male to female worker or simply performed by a female was generally considered less skilled and deserving of a lower payment by virtue of the operative being female. Women often earned as little as 45-50% of male wages under fixed wage structures. Even in the rare cases in which nominal equality existed, for example when both sexes were paid using the same piece-work levels, in reality gender differences within the workforce persisted. Women generally earned less than men because of their lower output, often due to men being given better quality materials and equipment. While male and female cotton weavers in Lancashire in theory received equal rates, males were assigned cloth types that brought higher rates of pay. The work was never equal. Overwhelmingly in textile factories women were increasingly assigned to tasks that were inferior in terms of status, pay, training provision and prospects. The division of tasks was never constant, but evolved over time depending on the conjuncture of technology, labour cost and social constructions of gender. The perceived ‘lower output’ of female workers was no doubt also due to women (particularly in household production) having to divide their time between textile production and domestic work to a greater degree than men. Christensen’s paper on Denmark cites textile employers as declaring in 1925 that it would be an injustice to give equal pay to women and men given that it was an “established fact” that women were less physically productive than men. This was a view similarly held by the vast majority of employers in textile history. However, as the same author also points out, keeping female wages low provided employers with a good price to productivity ratio. Certainly, the ‘lesser’ physical abilities of women did not inhibit the textile industry’s great use of female workers, and allowed companies to reduce their costs by utilising gendered (female) cheaper labour.

It should be noted, however, that while female workers could often be regarded as having the potential to undermine the position of their male counterparts, they could also themselves be vulnerable to such competition. Even cheaper or more easily exploited immigrant workers or ethnic minorities, for example, could replace or supplement the supposedly more tractable females who were already less expensive than men. Similarly, minors were a cheap and easily exploitable form of labour prevalent in nineteenth and twentieth century factories. In the nineteenth century, girls under the age of fourteen were common in Japan, while the Chinese industry employed girls as young as eight in the silk industry and some Macedonian factories employed girls as young as six years. Child labour often came from the poorest households and those without a home. In the nineteenth century, foundling children were employed in Brazilian factories, and orphaned children in government factories of the Ottoman empire. Orphans were also utilised in seventeenth century

Netherlands, though a gender distinction was made between orphan boys who undertook apprenticeships to train as weavers and orphan girls who remained (unapprenticed) spinners.

10

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004

A common view held by textile employers across the globe was that of the

‘family wage’ or ‘adult male wage’, where the male household head was considered the key breadwinner and any income earned by wives and children was considered

‘supplementary’ to this. This gave employers the excuse to maintain male wages at a higher level than those of their female colleagues (and indeed children) on the shopfloor, despite the disadvantages this brought male workers in respect of their labour being replaced by more cost-effective female labour. In Egypt, the idea of women’s earnings being supplementary to household income was considered a reason to pay female operatives in early twentieth century factories below subsistence wages.

Alongside gender, race and ethnicity was also used as a basis for determining wage levels in the industry. In late eighteenth century Brazil, indigenous workers were paid in cloth rather than cash and plantation owners’ wives and daughters worked alongside predominantly female slave labour, while in nineteenth century India spinning was often un(der)paid when performed by wives or by rural labour castes.

In eighteenth and nineteenth century Mexico, slave and convict labour was utilised, while in the USA prior to the 1960s, black men and women were denied production jobs or were given the dirtiest or most dangerous jobs on the shop-floor.

However, it was not all bad news. Even when female workers were paid less well than their male counterparts, textile work often gave them a greater economic strength and earning ability than they had previously held. A women weaving commercially in China in the mid-late eighteenth century could earn enough to support one-two adults and two children, while in the 1920s and 1930s rural women seeking factory work could earn enough to contribute at least half of the household income and in some cases even support the entire household and initiate their migration for her industrial employment. Young female operatives in Japan could significantly add to the rural household income, and their ability to keep their earnings for themselves and save for their own future rose over time, particularly after WWII.

Moreover, the undertaking of textile work generally gave women a higher wage than their counterparts in agriculture work. The overall demand for female labour in the textile industry therefore gave large numbers of women the opportunity to become wage-earners in their own right and in some cases a greater sense of independence via economic means. It was better news still in the Lancashire cotton industry, where wages were based not on the ‘traditional’ adult male wage but on the collective earnings of family members as a whole. The author comments that this denoted female weaving operatives as the “best paid women workers in Britain”.

Women in the Lancashire industry could also work after giving birth to children, which challenged the notion of a woman’s primary reproductive role. While maternity rights were granted in most countries during the twentieth century, textile work for a woman operative had previously usually ended upon her marriage and, if not then, upon childbirth (though in some cases a woman could continue to do piecework from the home). While some textile employers, like the large Japanese companies of the twentieth century, provided childcare facilities on factory grounds to enable mothers to return to work, the hiding of pregnancy from employers often led to terrible consequences for the unborn child as referenced in Cliver’s paper on China.

The transfer of textile production from the rural household to the factory over time also increased the ‘double burden’ for women in terms of their productive and reproductive work efforts, and could often lead to a complex ‘triple burden’ of domestic housework and childrearing, agricultural labour and factory work.

Gender also played a part in influencing the shop-floor and factory environment in the textile industry. The heavy utilisation of young and female

11

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 workers allowed employers to employ patriarchal and paternal controls over employees. These included housing workers within factory compounds, regulations and restrictions with regard to work breaks and leaving company grounds, reward and punishments systems, and the use of male supervisors to oversee women and children.

Factory shift-hours were long, ranging from 10-17 hours in the nineteenth century, until legislation prescribed industrial hours and in many cases placed restrictions on the use of female labour (especially the ban on night shifts in Japan, Britain and

India). Female workers were often subject to sexual harassment or abuse, either on the shop-floor or on the way to and from work.

Paternalistic personnel management could be seen as a form of

‘imprisonment’ in its worst light and a form of ‘benevolence’ in its best light. The

‘selling’ of young girls into the industry, exploitation by recruitment agents, the cramped and overcrowded living/working conditions that bred illness, and the six-day working week were not unusual conditions and reflected paternalism at its worst.

Improvements over time to working conditions brought seemingly altruistic paternalistic efforts, as young workers from poor backgrounds were given housing, food, education, recreation and shopping facilities and maternity benefits. In the case of Spanish women weavers in the early twentieth century, this paternalism translated into imposed silences during the working shift in stark contrast to their male colleagues who were allowed to chat and sing. In the case of young female operatives in 1960s and 1970s Japan it translated into considerable welfare benefits including free or heavily subsidised housing, health benefits and opportunities for personal educational advancement.

The existence of large numbers of women in modern textile mills aided the development of various female networks, which while they also helped employers in terms of their ability to introduce and train generations of female operatives, also gave individuals a group identity and consciousness as working-class factory women. In some respects their growing strength on the shop-floor and in the dormitories of industrialised mills no doubt meant, as referred to in the USA paper, that employers were forced to “reinvent paternalism” in order to stave of union strength and worker power. While it is certain that workplace conditions were miserable for many women

(and children) in modern textile factories under industrialisation, it is also true that their activism and consciousness as women reflected their dynamism as a workforce during the course of history. Young girls migrated long distances for textile employment, while older women combined paid production work with unpaid domestic work to support the prosperity of their families.

Gender, Organisation and Activism

The utilisation of both male and female workers in substantial parts of the textile industry set up the potential both for conflict and cooperation within the workforce, and for shifting employer preferences in a context of changing labour costs and production priorities. In many locations early textile industrialisation was characterised by conflict, with male workers, with or without collective representation, protesting against their replacement by cheaper female workers. Such protests are recurrent in the national stories of European countries such as Spain, in the Turkish and Egyptian dominions in the Middle East, in China, and in the New

World, both Mexico and the United States. Responses to such resistance and protest were varied, but including strategies such as shifting women into less mechanised, less skilled or auxiliary tasks, as shown in the case of Egypt, Mexico and Spain, reorienting women’s textile work into a life cycle phenomenon, thereby allocating the

12

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 work lower status and pay (as found in China, Japan, Spain and the US), or, most recently, finding an entirely new set up employing non-unionised, female workers, as in the case of the Mexican maquiladoras .

Formal organisation of textile workers came relatively early, and pre-industrial guilds were formed by textile workers in many countries, particularly in Europe.

However, these were very much a ‘fraternity’ in nature. Guilds usually restricted their membership to male textile artisans, though sometimes widows were allowed entry if they continued their husband’s craft. However, guilds required the supportive labour of non-member women and children and actively solicited this labour through their male (household-head) members. As noted earlier, therefore, guild membership was a direct way of gendering the formal and commercialised sectors of the preindustrial textile industry, and providing the male workers with more status within the labour force. This continued to be the view of early worker organisations in nineteenth century textile mills, where female workers were referred to as

“journeymen in skirts” in Denmark and “daughters of freemen” in the USA, in some respects relegating their worker status to an inferior or less independent level by virtue of their gender.

There was much resistance, often from male workers, to the incorporation of women in textile labour organisations, which meant their membership took time and energy. There was a failed attempt to organise female weavers in Denmark in 1874, and their organisation was not realised until a decade later when “male hand weavers realised they had to take colleagues in mechanized mills seriously”. Male textile workers would often initiate the formation of unions and female workers would follow their lead or be permitted access at a later date. There was of course a definite fear amongst male workers of being replaceable by female workers, particularly as lower-waged female labour was more cost effective for textile employers. Strikes in

China in the 1920s & 1930s were strikes by male workers to try and prevent such replacements. Those women workers who raised their heads from their seemingly

‘docile’ status and participated in early strike activity were something to be feared, referred to as “babbling Amazons” in the USA and “hot-blooded” in Denmark.

Although textile unions were led by and dominated by male workers, over time they realised the need to rally women workers in order for unions to gain overall momentum and power as organisations. There was sometimes an ulterior motive, however, as in the case of Spain where male workers hoped the unionisation of females and their increased wages would lead to their replacement by more male workers. Sometimes, arguments for the rights of female workers could be more simply viewed in the context of their female role within the family and within society, such as the willingness of male workers in Spain to increase the pay of women because it would add to the overall family income, or the male workers in Mexico who were “defending traditional female virtue with traditional male honour” against the abuse of female operatives by male supervisors. In the case of China, however, female workers took matters into their own hands and formed powerful ‘sisterhoods’ for mutual support and protection. In part, this was probably a response to a tradition in China of male workers joining large-scale sworn brotherhoods, but it also demonstrates the ability of women to organise in informal but powerful ways. The chapter on China notes that these sisterhoods and their YWCA links were later mobilised and used to great effect by the Chinese Communist Party after WWII.

Informal textile organisations where female workers could gather together were also found in friendly societies and mutual associations in England and Japan. Over time

13

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 textile organisations transformed themselves from male-only memberships to modern unions making demands for equal pay.

Throughout the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries, however, it would be fair to say that women textile workers often participated in strikes and other forms of organised protest in spite of lower rates of unionisation compared to male workers and their often weak representation by union organisations. The participation of female workers in labour activism and strikes was witnessed early on in the industrialisation process — as early as 1821 in the USA, in Denmark in 1886, in the

Ottoman Empire in 1908 and in Mexico in 1912. While strikes were often male-led forms of activism, women participated in large numbers and with ferocity, as demonstrated in the 1870 Fall River strike in the USA when female weavers

“confronted the knobsticks with violence – yelling, jeering, kicking and pummelling strikebreakers with their fists and throwing stones and dirt clods” alongside their male strikers. The overview of Spain by Smith et.al.

, commenting on a 1913 strike, noted that “women proved every bit as militant as their male folk in strike, contradicting stereotypes which portrayed them as meek and submissive”.

Women also participated in less direct and more subtle forms of protest alongside their direct strike activity, which has challenged their historically ‘passive’ image. Such action was discernable in the 1912 ‘Bread and Roses’ strike in the USA when women supported and sustained strike activity “from behind the scenes in the tenement streets and in the kitchens”. Christensen’s paper on Denmark also suggests that less direct activism by women workers (e.g. lower union membership) does not indicate that women were more indifferent to their working roles than men, but rather that high expectation of women’s reproductive role in society meant they had a different experience as industrial workers than their male colleagues and thus had to develop different strategies. This often led to their acceptance of their ‘female subordination’ and their participation in activism which defended male-centred jobs and wages in the industry. It could also be argued that women were keen to protect their families and their role within the household. When Spanish textile women participated in a 1913 strike to reduce hours it could be suggested that they were protesting the long factory hours which added to their double burden of productive and reproductive work. While any successful worker activism throughout textile history can be attributed to the power of labour unions, it is also fair to say that the participation of female textile operatives in both direct and indirect forms of protest contributed to the strength and success of union action.

It is clear from the Chinese case, for example, that sometimes female textile workers had a very unique and powerful role to play, as demonstrated by the case of the “Number Ones”. Women who had risen up through the textile ranks, the Number

Ones operated as recruiting agents, shop-floor bosses and leaders of activism and sisterhoods. Supported often by criminal gangs, they wielded a lot of power in the industry, to the extent they could also be accused of reinforcing a ‘patriarchal’ exploitation of young rural women, the so-called ‘plucking mulberry leaves’ trade in girls. They were a matriarchy in their own right and were often referred to as

‘godmothers’, standing out in a largely paternal industrial history. The Chinese textile sisterhoods were so strong that the Chinese Communist Party utilised their help in their 1949 revolution and liberation of cities.

Powerful leadership was also displayed by women workers in 1875 Fall River activism in the USA, when female operatives shamed their male colleagues by successfully striking after the men had already reluctantly accepted reductions to their wages. These women also spoke on public platforms, were vocal at strike meetings

14

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 and were active fund-raisers for the labour movement. The strident voices of these

Chinese and American women, and the recorded participation of female textile workers in strikes and other protest in many of the countries in this study, demonstrates a degree of consciousness and identity as proletariat workers that was developed by women themselves. This increased consciousness, autonomy and economic strength (as individual wage earners) often led women to settle in the urban areas rather than return to their rural homes, resist or delay marriage, fashion themselves as ‘modern’ women, and save for their own future.

Conclusion

The changes that have taken place in the gendering of textile work over the last four centuries have in many respects reflected gendered aspects of the evolution of the manufacturing sector as a whole. One aspect of this is the importance of state policy.

It is apparent that in a number of the countries considered here state policy had a significant impact on the development of the textile industry as a whole. In that context states also influenced the gendering of production. Consideration of these indirect effects of state policy lies beyond the scope of this paper, but two direct ways in which state policy has had an impact on gender aspects of textile work can be briefly noted. The first is through the broad thrust of labour policy as a whole, which was invariably closely tied to the wider ideology of the regime in question, including its adherence or non-adherence to free market principles. In Communist China improved benefits for workers were imposed on textile producers as on others, and the glorification of industrial labour associated with the party ideology had a significant impact on the identity and image of female workers in the industry. Other Marxistinfluenced countries, such as the Soviet Union, also promoted the image of female workers and sought to guarantee equal pay and status. The political control enjoyed by the ruling party in these cases went some way towards ensuring that the dictates of equality were met. Nationalist imperatives in wartime Japan also pushed towards greater gender equality in the workforce, including in textiles. By contrast, the populist Peron regime in Argentina also implemented policies designed to benefit workers, but found it often resisted by employers. In general, it may be suggested that the gender division of labour, and, indeed, divisions along ethnic lines, for example, have tended towards greater equality where political regimes have shown a tendency to curb the excesses of free market operation.

The second direct way in which states have been able to influence the gendering of textile work is through the implementation of targeted, specific legislation, usually in the form of protective legislation. There are many potential areas for such legislation, ranging from minimum wage legislation in recent years

(which may arguably undermine women’s comparative wage advantage compared with men), through to maternity provision, childcare leave and health and safety legislation. Most conspicuous in the case of the modern textile industry has been protective legislation aimed at curbing labour abuses or safeguarding the interests of particular segments of the workforce. The prohibiting of night work for women in the

UK in the 19 th

century was a major factor limiting the twenty-four hour operation of textile mills, since employers were reluctant to employ an additional shift of male workers to fill the night time gap. In Japan, the introduction of a ban on night work for women was resisted by employers for years, but when eventually imposed in 1929 if anything enhanced labour productivity and stimulated further feminisation of the workforce. The issue of night time working was also debated in India. The impact of such legislation has tended to vary across countries, but the extent to which protective

15

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004 legislation restricting the work conditions of one particular segment of the labour force, normally women, also acts to promote or undermine gender equality in that workforce, lies at the heart of modern textile production.

The process of the gendering of textile work in each country has also mirrored changing social perceptions of gender roles, and interacted with the process of technological change and capitalist development to produce new patterns of production and new understandings of what it means to be a male or female textile worker. Unlike some other industries, however, textiles has in all countries been more likely to employ both sexes within the same sector, often in similar jobs, laying the foundations for a sharper gender division of labour that reached its apogee in the most industrialised economies in the first half of the 20 th

century. The details of that process have varied considerably across the globe, but the prominence of the textile industry in manufacturing production everywhere, and its particular importance in the work of females, in both pre-industrial and modern times, mean that textiles is a crucial area for understanding the significance of gender in the labour process. In many respects gender is the most profound, and the most important division in the composition of the textile workforce. In some countries the historical experience suggests that under certain circumstances gender differences can be subordinated to the interests of class. More often, though, gender differences and the unequal relations of power between men and women have shaped the production process, the worker experience and the overall process of capitalist development, and have in turn been shaped by them.

In some respects it may be problematic to speak of common experiences that define the male or female textile worker, as we must be sensitive to enormous differentiation within the global industry. On the other hand, many of the issues on gender discussed in this paper seemed to emerge as commonalities and themes from many of the national overviews. The male-female differentiations and the voices of young women were not always specifically recorded in industrial history, but they can be uncovered through comparative studies such as these. And we may discover that women have gone from being ‘broken shoes’ (China) and ‘pitiful factory girls’

(Japan) to become the heroines of a new historical and industrial narrative.

16

Janet Hunter & Helen Macnaughtan Comparative paper Gender, Textile conference IISH, 11-13 Nov. 2004

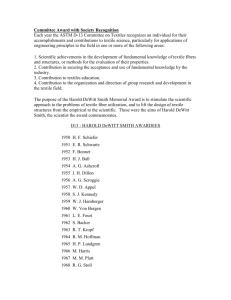

Table 1 — Proportion of females in textile workforce (19 th -20 th centuries)

Year Country

1841-1905 Spain (various cities)

Females as % of textile workforce

42-70

1973-1980

1853

1927

Spain

Mexico (2 cities)

Mexico (various regions)

49-57

8-12

3-41 (av.14)

1965

1875

1861

1920-1940

1929

Mexico

USA (3 cities)

India

Japan (spinning, weaving, silk)

Argentina (Buenos Aires)

60

53-73

40

54-86

63-75

1907

1906 & 1935

1906 & 1935

1908-1938

Egypt

Denmark (weaving)

Denmark (spinning)

Uruguay

10

60

80

40-62

17