Developing a Teaching Portfolio Background on Teaching Portfolios

advertisement

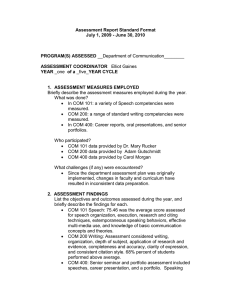

Shelley L. Smith PhD Instructional Development Services Developing a Teaching Portfolio Background on Teaching Portfolios Several lines of thought have gone into the development of teaching portfolios as represented by the various publications to be found in the bibliography. Boyer (1990) and the follow-up volume Glassick et. al. (1997) call for the documentation of teaching and learning in a matter akin to the documentation of disciplinary research. They see the scholarship of teaching and learning as a productive venue for a scholarly exchange of ideas about the promotion of student learning. Teaching portfolios advance the scholarship of teaching and learning by making teaching public thereby providing ways for scholarly critique of efforts to promote learning. The current manifestation of these ideas can be seen in websites for the Carnegie Academy for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (insert two URLs). The formative use of teaching portfolios has developed as a way to refocus faculty efforts on teaching and learning as well as provide a mechanism for faculty to share their insights and accomplishments with peers. Formative portfolios tend to be reflective and often reveal problems the portfolio owner faces in the classroom. The promotion of teaching portfolios for formative development has been championed the American Association for Higher Education through such publications as Edgerton et. al. (1991) and Hutchings (1996). A more recent publication, Hutchings (1996), suggests ways in which academic departments and programs can use teaching portfolios to improve curriculum and encourage the development of community among faculty. The summative use of teaching portfolios for the academic job search, promotion, and tenure centers on the portfolio as a way to document faculty skills in teaching and learning. Summative portfolios tend to put the best light on the portfolio owner's teaching. Useful suggestions for summative portfolios can be found in Seldin (1991) and (insert date). Discussion of the assumptions underlying the summative use of teaching portfolios is available in Centra (1993) and Chism (1999). Principles for Portfolio Development It is a career-long project which is never complete It requires clarity about formative and summative uses It is more effective if developed in community of peers Documentation and reflection are equally important Summative use of a Teaching Portfolio requires careful investigation as to precisely what is valued by the portfolio evaluators. The creation process is as important as the final product A carefully crafted teaching philosophy is central to the organization and content. An up-to-date curriculum vitae is an equally vital component It is difficult to get started, but once a routine is created, subsequent additions are less difficult. 10/18/07 1 Shelley L. Smith PhD Instructional Development Services ITEMS FOR YOUR TEACHING PORTFOLIO1 Faculty members should recognize which of the items, which might be included in a teaching dossier, would most effectively give a favorable impression of teaching competence and which might better be used for self-evaluation and improvement. The dossier should be compiled to make the best possible case for teaching effectiveness. The Products of Good Teaching Students' scores on teacher-made or standardized tests, possibly before and after a course has been taken as evidence of learning. Student laboratory workbooks and other kinds of workbooks or logs. Student essays, creative work, and project or fieldwork reports. Publications by students on course-related work. A record of students who select and succeed in advanced courses of study in the field. A record of students who elect another course with the same professor. Evidence of effective supervision of Honors, Master's or Ph.D. theses. Setting up or running a successful internship program. Documentary evidence of the effect of courses on student career choice. Documentary evidence of help given by the professor to students in securing employment. Evidence of help given to colleagues on teaching improvement. Materials from Oneself Descriptive material on current and recent teaching responsibilities and practices. List of course titles and numbers, unit values or credits, enrollments with brief elaboration. List of course materials prepared for students. Information on professor's availability to students. Report on identification of student difficulties and encouragement of student participation in courses or programs. Description of how films, computers or other nonprint materials were used in teaching. Steps taken to emphasize the interrelatedness and relevance of different kinds of learning. Description of steps taken to evaluate and improve one's teaching. Maintaining a record of the changes resulting from self-evaluation. Reading journals on improving teaching and attempting to implement acquired ideas. Reviewing new teaching materials for possible application. Exchanging course materials with a colleague from another institution. Conducting research on one's own teaching or course. Becoming involved in an association or society concerned with the improvement of teaching and learning. Attempting instructional innovations and evaluating their effectiveness. Using general support services such as the Education Resource Information Center (ERIC) in improving one's teaching. Participating in seminars, workshops, and professional meetings intended to improve teaching. Participating in course or curriculum development. Pursuing a line of research that contributes directly to teaching. Preparing a textbook or other instructional materials. Editing or contributing to a professional journal on teaching one's subject. 1 * From: R. Edgerton, P. Hutchings, and K. Quinlan, "The Teaching Portfolio: Capturing the Scholarship of Teaching," a publication of the AAHE Teaching Initiative, American Association of Higher Education, 1991. Washington, D.C. 20036. p 8. Reprinted with permission. 10/18/07 2 Shelley L. Smith PhD Instructional Development Services Information from Others Students: Student course and teaching evaluation data, which suggest improvements or produce an overall rating of effectiveness or satisfaction. Written comments from a student committee to evaluate courses and provide feedback. Unstructured (and possibly solicited) written evaluations by students, including written comments on exams and letters received after a course has been completed. Documented reports of satisfaction with out-of-class contacts. Interview data collected from students after completion of a course. Honors received from students, such as being elected "teacher of the year." Colleagues: Statements from colleagues who have observed teaching either as members of a teaching team or as independent observers of a particular course, or who teach other sections of the same course. Written comments from those who teach courses for which a particular course is a prerequisite. Evaluation of contributions to course development and improvement. Statements from colleagues from other institutions on such matters as how well students have been prepared for graduate studies. Honors or recognition such as a distinguished teacher award or election to a committee on teaching. Requests for advice or acknowledgment of advice received by a committee on teaching or similar body. Other Sources: Statements about teaching achievements from administrators at one's own institution or from other institutions. Alumni ratings or other graduate feedback. Comments from parents of students. Reports from employers of students (e.g., in a work-study or "cooperative" program). Invitations to teach for outside agencies. Invitations to contribute to the teaching literature. Other kinds of invitations based on one's reputation as a teacher (for example, a media interview on a successful teaching innovation). 10/18/07 3