When Growth Stops, What Then? Capitalism as a Crossroad.

advertisement

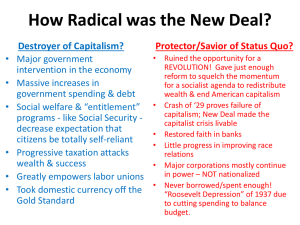

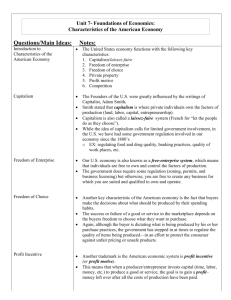

When Growth Stops, What Then? Capitalism at a Crossroad Ramapo College December 1, 2004 Peter Montague (peter@rachel.org; www.rachel.org; 732-828-9995) "Here's a riddle to keep you up at night: How come, at a time when the environmental movement is stronger and richer than ever, our most pressing ecological problems just get worse? It's as though the planet has hit a Humpty-Dumpty moment in which unprecedented amounts of manpower and money are unable to put the world back together again." --Time Magazine Aug. 26, 2002 I believe the answer to this riddle is growth. To prevent destruction of the natural world, sooner or later, total economic growth must slow and then stop. But capitalism requires continuous economic growth. Therefore, it would seem that, sooner or later, capitalism must be replaced by some alternative way of organizing production. What might that alternative be? One possibility is an idea called Economic Democracy. Let's explore this possibility. Part I : The Problem: Endless Growth on a Finite Planet Because we live on a finite planet, limits are apparent. Furthermore it is now a human-dominated planet. Through the activities of agriculture, fisheries, industry, recreation, and international commerce, humans cause three general classes of change; we (1) transform the land and sea -- through land clearing, forestry, grazing, urbanization, mining, trawling, dredging, and so on; (2) alter the major biogeochemical cycles -- of carbon, nitrogen, water, synthetic chemicals, and so on; and (3) add or remove species and genetically distinct populations -- via habitat alteration or loss, hunting, fishing, and introductions and invasions of species.[1] There is evidence that some limits have already been reached: ** global warming; [2] ** depleted ozone layer; [2] ** women's breast milk contaminated with hundreds of industrial poisons [don't get me wrong: breast-feeding is still the best way to nourish an infant]; [2] ** drinking water laced with low levels of viagra, anti-depressents, chemotherapy toxicants and several hundred other "personal care products" designed to be biologically active; [2] ** children's cancers, asthma, and other environment-related diseases increasing; [2] ** many species of birds, fish, amphibians and mammals already extinct, with thousands more soon to become so; [2] ** and these are just a few of the more obvious signs that we have exceeded some of the natural limits of the Earth. This list could be readily extended. Therefore, it seems apparent that sooner or later -- and probably sooner rather than later -- total global economic growth (growth in the amount of "stuff" moved around) must slow and then stop. To achieve this equitably, some "overdeveloped" regions will need to stop growing soon to make room for growth in other regions that need to continue growing to alleviate poverty. A slowing and eventual stopping of global economic growth does not seem possible under capitalism. Some of the problems of capitalism Capitalism defined 1) The bulk of the means of production are privately owned, directly or by corporations that are, themselves, privately owned. 2) Products are exchanged in the market -- prices of raw materials and of goods and services are set by supply and demand. Individual enterprises compete with each other in providing goods and services and this competition is the primary determinant of price. 3) Most people who work are "wage laborers" -- they work for other people who own the means of production. A capitalist can be defined as a person who owns enough productive assets that he or she can live without working (if he or she chooses to do so). This encompasses about 1% of the U.S. population. Capitalism has 4 manifestations: a) A consumer society b) Mysterious financial markets c) Savage inequality d) Deep irrationality in its overall functioning: ** Amazing technologies intensify, not reduce, the pace of work ** Our lives grow less secure, not more secure 2 ** In a world of deprivation, we must worry about overproduction ** The health of the global economy depends on what we all know is impossible -- ever-increasing consumption Brief discussion of some of the defects of capitalism ** Massive inequality ** Demoralizing unemployment ** Unnecessary overwork ** Excruciating poverty, nationally and globally ** Lack of real democracy ** Systematic and sustained environmental degradation Capitalism requires endless economic growth -- growth in the amount of stuff that is extracted, transported, processed, transported, used, transported and perhaps recycled but eventually discarded ** The basic capitalist maxim is, Grow or die. Every capitalist firm is under pressure to produce, make a profit, reinvest, and grow. Under capitalism, you have growth or recession. ** Capitalism's perpetual problem is weak demand, caused by excessive productive capacity. Therefore, demand must be created and stimulated by easy credit, a sophisticated sales apparatus, and production for export. ** Third World countries are induced to produce for export, and to export raw materials -- and overdeveloped countries must be induced to consume more because they are the main markets for Third World goods. ** To attract capital, poor countries must cut back public spending, keep wages low, open up their economies to outsiders, and ignore environmental harms. Environmental sanity requires the overdeveloped countries to cut back on consumption, and for poor countries to target their resources to eliminating poverty -- the exact opposite of what globalized capital demands. Capitalism has done very well by us, but now it is evident that it is threatening to destroy the biosphere, the biological platform that supports our economic well-bring. Conditions have changed, and our economic institutions must soon begin to change too. Part II: One possible solution -- Economic Democracy[3,4] The Basic institutions of Economic Democracy[3,4] 1. Worker-owned enterprises 2. Competitive market 3 3. Investment capital raised from a tax on capital assets (a flat-rate tax on land, buildings and equipment) Discussion: 1. Worker self-management. Each productive enterprise is controlled democratically by its workers. Workers no longer work for wages; they work for a fair share of the profits that their firm engenders. Worker-owned enterprises are fairly common now[5,6] ** They have a good track record ** They tend to be more efficient and more productive than traditionally-organized ownerhierarchy firms ** Naturally they don't all succeed ** Frequent question: Are workers competent to elect their boss? 2. The market. Enterprises compete with each other. Raw materials, instruments of production, and consumer goods are all bought and sold at prices set by the forces of supply and demand. This feature of capitalism is retained under economic democracy. 3. Social control of investment. Funds for new investment are generated by a capital assets tax (a flat-rate tax on land, buildings and equipment) and returned to the economy through a network of public investment banks. Workers control the workplace but they do not own the means of production, which are the common property of the society. Social "ownership" of the enterprise manifests itself in two ways: 1. All firms must pay a tax on their capital assets. In effect, workers rent their capital assets from society. 2. "Firms are required to preserve the value of the capital stock entrusted to them. This means that a depreciation fund must be maintained. Money must be set aside to repair or replace existing capital stock. This money can be spent on whatever capital replacements or improvements the firm deems fit, but it may not be used to supplement workers' incomes."[3] Since investment funds are generated publicly, not privately, their allocation is a matter of public concern, and means for allocating them must be developed. Each region of a country, and each community within each region, is entitled to its per-capita share of investment funds. Each region and each community gets its annual share of investment funds as a matter of right. 4 David Schweickart[3,4] favors allocation of investment funds by a network of democraticallycontrolled investment banks. They would allocate the funds based on criteria similar to the criteria used now by capitalist banks (profitability of the recipient enterprise) , but they would have an additional, ethical, mandate to try to create jobs with the funds. (A community could impose other criteria on local investment, such as preferring women-owned enterprises, minority businesses, "green" businesses, and so forth, if they chose to.) Economic Democracy and the Question of Growth ** Economic democracy does not require growth. ** Firms have an incentive to maintain market share but not to vanquish competitors and seize their markets. ** Firms can be quite content with zero growth, especially if they are employing new technologies to expand leisure and make work more interesting. Part III : Getting from Here to There Aim: Growth must be promoted in the Third World and reduced in the overdeveloped world. What poor countries need is: (a) genuine autonomy and freedom from interference; (b) control over locally-based foreign enterprises; (c) higher prices for raw materials and other products exported to rich countries. In the overdeveloped world, consumption must be reduced, but much of our excess consumption is "necessary" because of the structure of our built environment. Therefore, reducing consumption requires investment. Here, social control of investment becomes important. Other measures needed: More Worker Control and Producer Cooperatives ** Public financial and technical support for producer cooperatives and for worker buyouts of capitalist firms. ** Legislation encouraging more worker participation in capitalist firms and profit sharing. Worker representation on corporate board should be encouraged. More Social Control of Investment 5 ** Green taxes to make prices reflect true costs, including externalities, and to provide incentive for green innovation. ** Strict environmental laws to reduce degradation. ** Reregulation of transnational capital flows (beginning with a Tobin tax) ** Democratization of the banking system to make the Federal Reserve more accountable to the electorate and local banks more accountable to their communities ** Democratization of pension funds; make pensions more inclusive so everyone is covered; aim for "socially responsible" investment ** A capital assets tax, small at first, with proceeds to be used for community capital investment and to increase employment. Currently firms are taxed for the labor employ but not the capital, creating an incentive to substitute capital for labor. Fair Trade, Not Free Trade ** Tariffs should be imposed so no country can gain competitive advantage by poaying their workers less or by cutting corners on environmental protection. ** All proceeds from fair-trade tariffs to be rebated to poor countries; Continued work toward traditional American goals of equality, fairness, and justice: Existing social movements must continue their work and must begin to see that they have common interests in a new way of organizing production: ** environmental ** labor ** racial equality ** fight against homophobia ** mobilization for peace & against nukes ** gender equality ** global justice There is no silver bullet. As environmental and social conditions continue to deteriorate, as they almost certainly will under capitalism, inform yourself about the problems, develop alternatives (including an agenda of incremental steps that take us in the right direction), and talk to your neighbors, your friends, your fellow workers. Continue to build a movement for change. Organize. Organize! 6 Notes and references [1] Jane Lubchenco, "Entering the Century of the Environment; A New Social Contract for Science," Science Vol. 279 (January 23, 1998), pgs. 492-497. Available at http://www.rachel.org/library/getfile.cfm?ID=203 [2] These facts are well-documented; recent evidence has been cited in Peter Montague, "Rachel's #805, Living Within Limits," (New Brunswick, N.J.: Environmental Research Foundation, November 25, 2004); available at http://www.rachel.org/bulletin/index.cfm?issue_ID=2483 [3] David Schweickart, After Capitalism (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002); ISBN 0-7425-1300-9. 192 pgs. [4] David Schweickart, Against Capitalism (New York: Westview Press [HarperCollins], 1996); ISBN 0-8133-3113-7. 387 pgs. [5] Len Krimerman and Frank Lindenfeld, editors, When Workers Decide; Workplace Democracy Takes Root in North America (Philadelphia: New Society Publishers, 1992); ISBN 0-86571-201-8. [6] Greg MacLeod, From Mondragon to America; Experiments in Community Economic Development (Sydney, Nova Scotia: University College of Cape Breton Press, 1997); ISBN 0920336-53-1. [7] George Cheney, Values at Work: Employee Participation Meets Market Pressure at Mondragon (Ithaca, N.Y.: ILR Press, 2002); ISBN 0801488168. 7