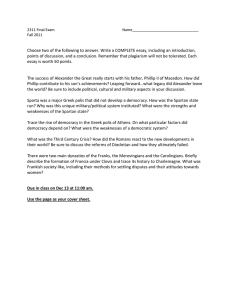

Alexander III and the Hellenistic World.doc

Alexander III and the Hellenistic World

I. Phillip II and Macedon

By 369 B.C., no Greek poleis could claim hegemony over the others. The Peloponnesian Wars had siphoned the wealth of Athens and the broken the military system of Sparta. There wa s a new power in the Greek Peninsula however. In the north, the kingdom of Macedon was on the rise, under the leadership of it’s king, Phillip II.

Although the Macedonians spoke Greek, the Greeks city-states considered them one step up from barbarians. Macedon was a national kingdom, not a polis, or even a collection of poleis. In addition, the king personally led the cavalry, the aristocratic warriors, into battle. This, of course, led to a high turnover of monarchs. Phillip was special because he managed to survive and expand Macedonian territory.

Phillip was able to increase Macedonian power by exploiting new gold mines, which gave him wealth to increase his military. Furthermore, the Macedonian population was large, and fought for their king and their country, something the Greeks in the south were no longer willing to do (the Spartans were now hiring themselves out as mercenaries). Phillip also changed the composition of the hoplite phalanx, making the shield smaller, the spear longer, and the spear point breakable. With a highly mobile infantry and a cavalry, the Macedonian army was fearsome.

There was something else about Phillip though. He had ambition. He stated that his goal was to unite all of Greece and free Asia Minor of Persian rule. He would conquer the Persian Empire itself. To do this, he had to unite the Greek poleis behind him, no easy feat. As Phillip and his Macedonians moved south,

Phillip practiced a particular brand of diplomacy…he married the daughters of conquered leaders.

Although marrying into the local ruling family was sound strategy to pacify a region, it made Phillip’s queen Olympias very uneasy. There were no r33ules of primogeniture for the Macedonian throne.

When the king died, whomever of the royal family was most qualified to lead the army was chosen by the Macedonian aristocracy to ascend the throne. And Olympias wanted her beloved son, Alexander, to be the next king. She wanted no competition from any male children that might result from Phillip’s subsequent diplomatic marriages.

Phillip had a daunting task. He had to subdue AND unite Greece behind his plan to conquer Persia. He had to contend with his queen, who actively disliked him. He had to train his eldest son, Alexander, to take over Macedon. And he had to make preparations for his grand invasion of Persia. In 338 B.C., at the

Battle of Chaeronea, Phillip successfully defeated the Greeks and created the League of Corinth, a coalition of the Greek states, in order to start his conquest of Persia. Before he could lead the Greeks to victory over Persia, however, Phillip was assassinated at Aegae in 336 B.C. His 19 year old son Alexander was proclaimed King of Macedon.

II. Alexander the Great

Alexander the III of Macedon was and is a legendary figure in both history and culture. By the time of his death at the age of 33, he created one of the largest empires in human history. It was also short-lived, lasting only during his lifetime.

Alexander had a good headstart in life. His father, Phillip II, provided him with the best education possible. For three years, he and his companions, other Macdonian youths of aristocratic families, were tutored by Aristotle. Alexander was also trained in the military arts. At the Battle of Charonea, he commanded the left flank of the Macedonian army. On the other hand, he had frequent clashes with his father, because he was very close to his mother, Olympias, and took her side when his parents fought.

Although Phillip took numerous wives, Alexander’s careful education and training made it clear that

Phillip intended for his son to succeed him.

There are no extant sources for Alexander’s life. The records that exist were written about five hundred years after his death. Although based on earlier works, since Alexander the Great was an almost mythical figure by the 1 st century AD, historians must read the sources carefully. He inherited the Greek war against Persia. And since the dreaded Phillip was dead and a teenager was on the throne of

Macedon, the Greek poleis started deserting the League of Corinth. Alexander quickly proved that he was his father’s equal. Taking the Macedonian army south into Greece, his show of force convinced the

Greeks to rejoin the League. The Persian expedition could begin.

III. The Persian Invasion

In 334 B.C. Alexander and the combined Macedonian/Greek army crossed the Hellespont into Asia with forty thousand infantry and six thousand cavalry. Since they had very little supply ships, Alexander had to keep his army moving. He also needed to win every battle; if he lost, the Greeks would abandon the

League. The King of Kings of Persia, Darius III, considered the invasion a minor distraction. He ordered the satraps of Asia Minor to take care of the problem. This was a huge mistake, considering Alexander was a brilliant military commander. At the Battle of Granicus in 334 B.C., Alexander defeated the satraps of Asia Minor. The importance of the Granicus is that it gave the Macedonians a port on the eastern side of the Aegean in which to ship in supplies. Alexander and his army then moved down the coast, subduing the port cities. Again, not only will this give the Macedonians a supply line to the Greek poleis, but it prevented the Persian navy from supplying the satraps in Asia Minor. Alexander accomplished the first major goal of his expedition.

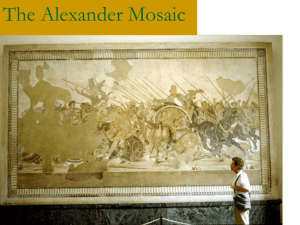

The second major battle of the Persian conquest occurred in southern Turkey, at Issus, in 333 B.C. This time, Darius III personally took part in the battle (from the rear). In a stunning cavalry charge, Alexander and his companions personally broke through Darius’ bodyguards and made for the Persian king himself, while the Macedonian infantry held off the main Persian army (the Macedonians were outnumered more than 2:1). Darius fled the battlefield and the Persian army, seeing the King of Kings running, broke.

It was a stunning victory for the Greeks and Macedonians. Darius went back to the heart of his empire and Alexander continued moving down the coastline, into the land bridge area, subduing the coastline.

With the capture of Tyre in 332 B.C., the last major Persian port on the Mediterranean was in

Alexander’s control. In late 332 B.C., Alexander marched into Egypt, where he was hailed as liberator…and Pharoah. He founded a city there, Alexandria (ego much?), one of about twenty cities that he generously gave his name to. By the way, he founded other cities, including one named after his horse, but the most famous one is Alexandria, Egypt. Meanwhile, in the Persian heartland, Darius was assembling a vast army to finally defeat the Macedonians.

The last of the major battles between the Macedonians and the Persians took place at Gaugamela in 331

B.C. Again, Alexander won a stunning victory and Darius had to flee the battlefield. By this time, Darius’ satraps were fed up with his defeats, and one of them, Bessus, killed Darius while the King of Kings was heading towards the eastern provinces. Alexander rewarded Bessus by hunting him down and having

him executed. Kings don’t like it when the rabble kill their fellow kings. As a result of Darius’ death,

Alexander controlled the western part of the Persian empire. He secured the heartland, and the treasury cities of Babylon, Susa and Persepolis (which caught fire during the seige, deliberate or not?). Then he marched east and subdued the eastern parts of the empire, in part by marrying the daughter of one of the local satraps, Roxane. When Alexander tried to cross the Hyphasus River into India, his troops rebelled, and he was forced back into Persia. To cement his power in Persia, Alexander married the daughter of Darius III in 324 B.C. Within a year, however, he was dead. Alexander’s death in 323 B.C. marks the end of the Hellenic Age and the start of the Hellenistic Age.

III. The Hellenistic World

So, a teenager starts out to conquer the eastern Mediterranean Basin and central Asia, and succeeds.

Soon after his death, however, Alexander’s empire falls apart. His first wife, Roxane, bore Alexander a posthumous son, but both she, the son, and Alexander’s mother were killed in power struggles that ensued after 323 B.C. The empire Alexander conquered eventually devolved into three major kingdoms/empires, under the control of Macedonian generals: Ptolemaic Egypt (Ptolemy I Soter, supposedly a half-brother of Alexander), the Seleucid Empire (Seleucicis I Nicator), and Antigonid Greece

(Antigonus I Monophthalmus, which means “one-eye”). All of these would would continue until another superpower defeats them: the Romans.

The Greek/Macedonian conquest of the “known” world produced a huge shift in the Greek way of thinking. The Greeks could no longer think in terms of the polis, indeed, could no longer define themselves in terms of the polis. They had been part of something much, much larger. They had been away from home, from their city-state, from Greece, for years. While we may think of the Greek polis as urban, the Hellenistic world is truly “urban”, with trade, commerce, intellectual life, foreigners coming and going. The average citizen no longer has a unique and individual role in the polis. Instead, the

Greeks, and the empires that are the inheritors of Alexander, set up monarchies, aided by bureaucracies. The new city is impersonal, not intimate. Greeks immigrate throughout the differing empires that are created after Alexander’s death, and bring with them Greek culture. Buddha will start to look like Apollo, the Hebrew scripture is translated into Greek and the great library at Alexandria started to preserve texts. Cultural transmission went in the other direction. Eastern religious mystery cults will find their way into the Greek world (and eventually into Rome). These mystery cults, dedicated to deities such as Isis and Mithra, appealed especially to the lower classes. They offered salvation, peace, an afterlife, but they also prescribed rituals that needed to be followed, such as special diets and holy days.

Of course, we must talk about philosophy. Greek philosophy undergoes a radical change during this time period. Because the Greeks found themselves living in a much larger world, outside of the polis, the new philosophical schools focused on how to live in this world. While classical philosophy was idealized

(Plato) and centered on esoteric questions, Hellenistic philosophy was more about “self-help” guides, i.e. how do I, the individual, live in this new cosmopolitan society? Keep in mind, philososphy was also for the educated; the average lower class farmer didn’t care squat about “Good Living in the Hellenistic

World for Dummies”.

There were two main schools of philosophical thought. The first, the Epicureans, named after Epicurus

(342-271), said that pleasure should be maximized and pain minimized. This is sometimes misunderstood today. Epicureans didn’t advocate a hedonistic lifestyle. After all, boozing it up, staying up all night, and gorging on cheesecake will lead to pain. What the Epicureans advocated then was

pleasure of the mind. Live simply, in moderation, don’t worry about things that you don’t have to, and cultivate inner peace and tranquility. Easy right?

On the other hand, the Stoics, with their sage Zeno (335-263 B.C.), said that one single divine plan ruled the universe and everyone in it. The role of humans was to accept this plan, and live accordingly.

Therefore, if you accept your fate, you will achieve peace and harmony with the universe. Suffering is irrelevant…ignore it. The universe was not irrational however. It was part of the Logos, reason, and since man was part of the universe, man was part of the Logos too. Hence, you can’t escape fate, accept it, find peace, and go on with your life…stoically. Oh, and since all were part of the Logos, we were/all equals, kings, slaves, aristocrats, goat-herders.

There were other philosophical “schools”. The Skeptics argued that since everything was constantly changing, true knowledge was impossible. Therefore, humans could never be happy, especially intellectuals. Some of my favorite philosophers were the Cynics. The Cynics rejected the material world and the possessions and responsibilites that go with them, as well as the conventions of civilization. The most famous Cynic was Diogenes (412-323 B.C.). Diogenes lived in a bathtub in the marketplace and indeed, the word cynic itself comes from the Greek word for dog, since Diogenes urinated, defecated, slept, ate, and apparently masturbated in public. The most famous story about Diogenes said that

Alexander came to meet the famous philosopher and asked him if he needed anything. Diogenes replied, “you can move, you’re blocking the sunlight”. Alexander allowed him to live.