Agent Green Over The Amazon - Drug War Policy Threatens to Unleash Havoc in South America

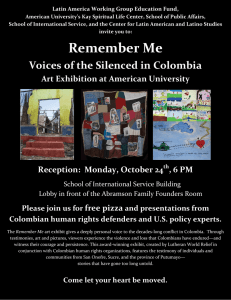

advertisement

Agent Green Over The Amazon Drug War Policy Threatens to Unleash Havoc in South America An Investigative Report from Lago Agrio, Ecuador By Jeff Conant The Curse of Lago Agrio Rumors of the impending release of a genetically modified fungus as part of the War on Drugs in Colombia have been raising concerns among environmentalists and regional officials that a grave ecological and social crisis may be unfolding in the region. At the same time, heightened violence on the ground in Colombia is putting pressure on bordering nations as they anticipate the arrival of thousands of refugees from the growing civil war. On July 19 the Ecuadorian daily paper El Comercio ran a front page article entitled “Exodus Arrives at Sucumbios: the Wave of Refugees Grows.” According to the article, 5000 Colombian refugees had recently arrived in the Ecuadorian state of Sucumbios, on the border of the two Andean nations, and an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 more were expected in the following weeks. The cause of the mass exodus was heightened violence in the Colombian civil war. More specifically, this wave of refugees was coming from the Putumayo region of Colombia, where massive doses of the U.S.-made pesticide glyphosate, better known as Roundup, are being sprayed to destroy coca and poppy plantations as part of the U.S.-sponsored War on Drugs. A few weeks later, arriving in Lago Agrio, the capital of the state of Sucumbios - and capitol of the Ecuadorian oil industry - I found that the Comercio had exaggerated the figures, but not the fear. According to Luis Yanez of the Frente de la Defensa de La Amazona (The Front for the Defense of the Amazon), there were as yet no “official” refugees, although the fumigations were, and are, well under way. With constant newspaper reports about the pesticide spraying, the refugees, and rumors of a mysterious fungus being dumped over the Amazon basin by the U.S. DEA, people across Ecuador fear the worst. On the eve of a prolonged conflict between Colombia’s many factions and the growing U.S. military presence in the region, Ecuador has little choice but to watch itself be dragged into the melee against its will. The bishop of Sucumbios, Monseñor Gonzalo Lopez Mareñon, denied the newspaper reports of 5000 refugees. But he had recently formed a group called the Asemblea de la Sociedad Civil (Assembly of Civil Society), which, together with the Frente de la Defensa de La Amazona and the UN High Commission on Refugees, was meeting to begin preparations for the impending crisis. Barring the closing of the border - which will only exacerbate the situation—nobody doubts that refugees will arrive, and in ever-increasing numbers. Lago Agrio is not prepared to receive these refugees. The city itself has a troubled history, and is one of the poorest and most violent cities in Ecuador. As little as thirty years ago Lago Agrio, then known as Nueva Loja - was the heartland of the Cofan people, an indigenous tribe renowned for their bravery, skill at warfare, and knowledge of traditional medicine. But when Texaco struck oil there 1962 and changed the town’s name to Lago Agrio after Sour Lake, Texas, site of their first oil deposit back home - the region’s history took a sharp turn for the worse. Forty years later the Cofanes have been reduced to a few thousand proud stragglers clinging to their traditions, and Lago Agrio, on the border of Colombia, has become one of the most polluted and fearful areas in this small, poor, but relatively peaceful nation. Regular border crossings by Colombian drug-traffickers and the presence of low-paid migrant workers, along with the difficult conditions of work in the oilfields, causes a general instability in the town, and warnings to stay in at night. The complete absence of facilities for an impending flood of refugees - especially refugees whose only livelihood is growing, processing, and transporting cocaine—has begun to raise fears, not only in Lago Agrio but throughout the nation, that the effects of Plan Colombia will spill over the border, deepening Ecuador’s already grave social and economic crisis. The wave of pesticide fumigations rumored to increase at any moment, but which, until now, seem to be shrouded in secrecy, will only make matters worse. Plan Colombia The fumigations, aimed at destroying plantations of poppy and coca and the livelihoods that depend on illicit cultivation, are part of Plan Colombia. Plan Colombia, developed by the U.S. and the European Union with the support of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, has as its objective the opening of markets and the stimulation of foreign investment in Colombia. According to its critics, the plan is given a different face depending on its audience. But it seems to have several specific objectives which remain more-or-less fixed: * The implementation of measures to attract foreign investment and to promote the expansion of markets, strengthening treaties that protect foreign investment and free trade as promoted by the World Trade Organization. * Destruction of illegal cultivars in the region of Putumayo and other zones in Southern Colombia, and their substitution with “productive projects, principally permanent cultivars [coffee, banana, sugar, African palm]…by way of strategic alliances” between investors and large and small landholders which will offer “alternative employment opportunities and social services to the population of areas under illicit cultivation.” * Reestablishment of military control in these zones, and modernization of the Armed Forces. * Institutional reform, including the struggle against corruption and the defense of human rights. * Reactivation of the economy. As basic tenets of globalization and WTO unilateral policy, these same principals, applied in Mexico in the mid-1990´s, led to destabilization of the rural population and widespread civil unrest. The implementation of NAFTA in Mexico hinged upon fundamental policy shifts, such as the erasure of article 27 from the Mexican Constitution. Article 27, the right to hold land in common, protected ancestral indigenous territories from being bought and sold. Its removal from the constitution aimed to increase investment and stimulate the economy. Instead, it lead to the Zapatista uprising of January 1994 and a prolonged war of attrition that continues to the present day. It is hard to imagine that further militarization of the War on Drugs, and the leveling of prices that will come with Plan Colombia and the pending Free Trade Agreement for the Americas will not have a similar effect. As the example of Mexico has shown, Free Trade favors the corporations and large landholders - those that can show immediate profit and whose economies of scale can withstand the leveling of prices on the global market. The small landholder is moved off his land and the landless peasant is forced to work at less-than-subsistence wages. The landless peasants and small landholders in Southern Colombia, who currently subsist by planting and processing coca, and who have been increasingly caught between the guerillas and the paramilitaries, will continue to be forced to migrate to other zones, both to find work and to escape the escalating violence and the aerial fumigation. Over the past ten years more than 1.5 million Colombians have been displaced, and at least 35,000 have been killed. An estimated 2 percent of Colombia´s population - some 800,000 people - have fled the country since 1996, most of them to the United States. But while the middle classes take refuge in the U.S., those with less resources are forced across the border into Panama and Ecuador. A refugee community of some 800 people, and growing, has taken root in Panama´s dense and nearly impassable jungle province of Darien, at the bottom of the Central American isthmus, bringing a new source of destabilization to that wracked and recently demilitarized nation. And, like in Ecuador´s impoverished Oriente, the existing infrastructure barely supports the local population, let alone the arrival of immigrants and refugees. As long as cocaine remains at once illegal and in high demand - primarily in the U.S. - it will be impossible to compete with its viability as a cash crop. Its destruction may in fact have the reverse effect - it will raise prices and increase the incentive to produce. Despite the massive campaign to destroy illegal cultivars in Colombia over the last several years, production has doubled, and the violence accompanying it has increased. U.S. State Department figures show that in spite of intensive herbicide spraying and other forms of forced eradication, the area in production increased by 200% between 1992 and 1999. In 1999 alone, the area under cultivation increased by 20,200 hectares (50,500 acres). It seems clear that a strategy of eradication, without the accompaniment of a plan to reduce poverty and secure livelihoods for the people of the zone, is bound to fail. Operation Roundup David Hathaway, a U.S. economist and expert in matters of biosecurity working in Brazil, affirms that “the application of Roundup in rural areas has been a disaster overall. It is a disaster because the problem is badly diagnosed. Or, I should say, the problem is well-diagnosed: the problem is to sell more Roundup.” He continues, “It is possible and viable to eradicate coca and poppies in a given field. This much is true. What is not possible is to eradicate these cultivars in general.” Monsanto´s Roundup, chemical name glyphosate, was introduced to the market in 1974 as a wide-spectrum herbicide. It is currently one of the most widely used herbicides in the world, with sales reaching twelve billion dollars annually. It is also one of the most toxic. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the ingestion of 200 mililiters of Roundup is immediately lethal. Aside from such immediate effects of acute exposure, long-term exposure has been shown to cause damage to human reproductive systems and genetic material. Among the effects of exposure are convulsions, acute respiratory problems, loss of muscle control, unconsciousness, destruction of red blood cells, cardiac depression and loss of fertility. The EPA has shown Roundup to increase levels of phosphorous, potassium and Urea in the blood, and to produce pancreatic lesions and abcesses in the kidney, liver and heart. Among its unfortunate side effects in the environment is high toxicity to earthworms, bacteria and rhizomatic fungus - all of which are essential to the long-term health of agricultural soils. It is up to 100 times more toxic to fish than it is to humans and, like other pesticides, it is subject to bioaccumulation - meaning that the level of toxicity grows with each step up the food chain. A person who regularly eats fish poisoned with Roundup receives a dose much greater than direct exposure. A 1993 study by the University of Colorado revealed that Roundup is the leading cause of pesticide poisoning in home gardeners in the U.S., and the third most dangerous pesticide in commercial agriculture. Due to such high toxicity both to humans and to the natural environment, the use of Roundup as an agent in the War on Drugs bears strong resemblance to the infamous use of the defoliant Agent Orange in South Vietnam. Operation Ranch Hand - the code name for the application of Agent Orange over 6 million acres of Vietnamese jungle between 1961 and 1972 - has left a legacy of at least 500,000 reported birth defects, as reported by the Tu Du hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology in Saigon. The use of Roundup over Colombia threatens to leave a similar legacy. In 1998, under pressure from the U.S., Colombia began the testing and application of a second herbicide in the Putumayo region. The herbicide, tebuthiuron, manufactured and sold by Dow Agrosciences as Spike 20P, is used in the U.S. mostly to control weeds on railroad beds and under high voltage lines far from crops and people. American and Colombian officials, complaining that the liquid Roundup has only destroyed about 30% of the plants sprayed, have been moving toward use of tebuthiuron, which comes in a granular form. Because Roundup must be sprayed from a low-altitude early in the morning when winds are calm and temperatures are lower, guerillas often fire at the low-flying planes. Tebuthiuron pellets, dropped from higher altitudes in any weather, day or night, make planes less vulnerable to ground fire. However, the environmental risks of this chemical agent make Colombian officials wary. Former Colombian Environmental Minister Eduardo Verano has said the effects of tebuthiuron on agricultural areas are still unknown, and its use will increase deforestation by forcing coca growers deeper into the jungle. In a 1998 interview with the New York Times, Mister Verano said, “We need to reconsider the benefits of chemical warfare. The more you fumigate, the more the farmers plant. If you fumigate one hectare, they´ll grow coca on two more. How else do you explain the figures?” Even Dow Chemical, the manufacturer of the herbicide, has spoken out against its use in Colombia. “Tebuthiuron is not labeled for use on any crops in Colombia, and it is our desire that the product not be used for coca eradication,” the company said in a public statement. Dow cautioned that the chemical should be used “carefully and in controlled situations,” because “it can be very risky in situations where terrain has slopes, rainfall is significant, desirable plants are nearby and application is made under less than ideal circumstances.” After years of lawsuits and public outcry over the use of Agent Orange also produced by Dow - the company said that it would refuse to sell tebuthurion for use in Colombia. However. According to the New York Times report, American officials have noted that Dow´s patent on the chemical has expired, allowing others to manufacture it. Agent Green The application of a second “Agent Orange” over the Colombian Amazon, has caused tremendous alarm among international environmentalists and inhabitants of the region. But residents of Southern Colombia and the Ecuadorian border region of Sucumbios are now expecting a new and even greater threat to their health and their ecosystem - the release of a biological control that environmental activists are referring to as “Agent Green”. Fusarium Oxysporum is a fungus native to temperate and tropical zones. In its natural state it is well-known as a plant pathogen that affects the roots and vacular systems of a variety of cultivated plants, causing disintegration of cells leading to withering, rot and death. Doctor David C. Sands, a plant pathologist at the University of Montana and one of the chief researchers on Fusarium Oxysporyum (FO) calls it “an Attila the Hun disease,” noting that there are strains of fusarium for virtually every cultivated plant and many wild ones. Some species of fusarium have also been known to cause illness in humans, especially those with depressed immunity from cancer or HIV-AIDS. The fungus was first identified as a possible weapon in the drug war by CIA scientists in the early 1980´s. In 1987 Doctor Sands was working in his Montana laboratory when he received a call from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, asking him to contribute his knowledge of plant pathology to the War on Drugs. The department had been experimenting on a legal coca plantation in Peru - previously owned by the Coca Cola company, but abandoned for greener, and safer, pastures in Hawaii. The USDA had taken over the plantation from Coca Cola to use as a test plot for herbicides. Ironically, the control plot that was not being sprayed was infected and largely destroyed by a mysterious pathogen. When Doctor Sands came down to investigate, he found that it was a naturally-occurring strain of fusarium. Dr. Sands took a culture of the fungus and tested it on a three-acre plot. Nearly all of the plants died. Since then, the fungus has been isolated, tested and developed as a biological herbicide at the University of Montana, in conjunction with the USDA and U.S.-based transnational Ag/Bio Con, Inc. In 1999, the Federal Government hoped to use fusarium to eradicate marijuana plantations in Florida, but the proposal was shot down by the Florida State EPA with the support of many private and public sector environmental groups. The director of the Florida EPA said, “It is difficult, if not impossible, to control the dispersal of fusarium species. The fungus can mutate and damage a wide variety of crops. Fusarium species are more active in warm soils and can remain active in the soil for years.” Despite these conclusions, on July 6 of this year - in the shadow of the U.S. approval of a $1.3 billion aid package to Colombia - the New York Times reported that Colombia had agreed to begin using the fungus “under pressure from the United States.” Colombia’s acceptance Fusarium Oxysporyum was one condition of the aid package’s approval. However, on August 22, President Clinton overruled Congress and retracted this condition, severing the link between U.S. aid and the use of FO, stating that the U.S. will not use Agent Green until “a broader national security assessment, including consideration of the potential impact on biological weapons proliferation and terrorism, provides a solid foundation for concluding that the use of this particular drug control tool is in our national interest.” Juan Mayr, the Colombian Minister of the Environment, assured that Colombia would begin “a program of research—and only research—on the use of biological controls.” But many environmentalists and people living in the region are still concerned that the fungus will be released without sufficient testing, and despite its known hazards. Lucia Gallardo, Coordinator of the Biodiversity and Biosecurity Campaign for Accion Ecologica, a Quito, Ecuador-based environmental advocacy group, affirms that the fungus is catalogued as a biological weapon in the list of the Protocol to the Biological and Chemical Weapons Convention. Biological Warfare Doctor Raul Moscoso, Ecuadorian magistrate and candidate for Attorney General, has given an extensive analysis of the regional and international accords violated by the fumigations both of chemical herbicides and of the fungus. The fumigations are in direct violation of the Cartagena Agreement of Andean Nations, the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity, and the globally ratified Convention Prohibiting the Development, Production and Storage of Bacteriological, Biological and Chemical Weapons. Doctor Moscoso is a vocal critic of Plan Colombia, stating that “This plan will not eradicate narco-trafficking. This plan will not terminate drug dependency. What this plan will do is bring about irreversible and irreparable social and environmental costs.” In refuting the use of the fungus under international law, Doctor Moscoso cites primarily Decision 391 of the Cartagena Agreement (a treaty between the Andean nations Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Bolivia and Peru), which specifically deals with “Access to Genetic Resources.” This decision strictly prohibits the use of genetic material in the fabrication of biological weapons or any practices that may be harmful to the environment or human health. He cites as well the Biological and Chemical Weapons Convention, which states that the ratifying bodies - nearly all of the nations on the globe - “agree not to develop, produce, store or in any form acquire or retain, under any circumstances, microbial agents or other biological agents or toxins, regardless of their origin or mode of production, in kinds or quantities that are not justified for prophylactic, protective, or other peaceful ends.” A third agreement breached by this joint policy of the U.S. and Colombia is the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity, signed by 157 nations during the historic meeting in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992. Article 3 of this convention confirms “the obligation to ensure that activities carried out within the jurisdiction of a state or under its control do not threaten the ecological balance within other states.” Article 8 binds member parties to ”Promote the protection of ecosystems and natural habitats without introducing exotic species that could threaten ecosystems, habitats or species.” Article 14c states that “Each member nation will promote the notification and exchange of information regarding activities in its jurisdiction which could foreseeably have adverse effects on the biodiversity of another state, and will notify immediately in case of the emergence in its jurisdiction or control of imminent dangers for biodiversity under the jurisdiction of other states.” That is to say, both Colombia and the U.S. are engaged in chemical and biological warfare in violation of international law and their own constitutions. According to the July 6 New York Times report (“Fungus Considered as a Tool to Kill Coca in Colombia”), lawyers at the White House and the State Department spent years debating whether or not the use of Fusarium Oxysporyum violated international conventions on biological warfare. They came to the conclusion that international law would not be violated if Colombia made its own decision to test or use the fungus. One U.S. intelligence official who maintains a stance against the fungus is quoted by the New York Times as saying, “I don´t support using a product on a bunch of Colombian peasants that you wouldn´t use against a bunch of rednecks growing marijuana in Kentucky. And there is definitely less than unanimous support for this in Colombia.” Colombian officials say that the first step is to see if this fungus already exists in Colombia, to ensure that they are not introducing an exotic species. “If fusarium is not there, we won´t study it,” said Mister Mayr, the Environmental Minister. However, rumors abound that a transgenic variety of Fusarium Oxysporum has been developed for use against coca plantations. According to the USDA, a variety of FO found on potatoes has been used as the basis for a genetically modified fungus with heightened virulence against coca plants. At a conference on July 24 at the Centro Internacional de estudios superiores de comunicación para America Latina (CIESPAL) in Quito, U.S. biosecurity expert David Hathaway affirmed, “Transgenic spores of this fungus have been developed in U.S. military laboratories. If transgenic varieties of this fungus are being tested in Ecuador, or have been tested in Colombia, we don´t know. No one knows…and if they do know, they´re not telling. We don´t know but we are very worried.” If in fact this fungus is being tested in Colombia, residents of that nation and its neighbor states have good cause for alarm. As a species with a high degree of variability the fungus can mutate rapidly, infecting a wide variety of cultivars in a short time. In its natural form it can survive in the soil from ten to forty years, and different varieties of the fungus are pathogenic to a vast number of cultivated plants, including: potato, vanilla, sunflower, date, coffee, avocado, cabbage, celery, squash, grape, soy, tobacco, melon, sesame, beet, African palm, eggplant, cotton, clover, eucalyptus, and many more. The release of fusarium in the Amazon basin, one of the world´s most biodiverse regions and the home to innumerable species not found anywhere else on the planet, puts at risk not simply a list of staple crops and the human inhabitants of the region, but the entire ecological balance of the Amazon. According to scientists working with the Sunshine Project, an international watchdog group devoted to the study of biotechnology and environmental law, four plants of the genus coca erytroxylum—wild relatives of coca native to Colombia—are on the endangered species list and will likely be among the first to be affected. One of these is host to a rare butterfly - Agrias spp. - which is also on the endangered species list, and whose center of speciation is in the region of the Upper Putumayo - precisely the region of most intense fumigations, and where the strongest release of fungus would be slated to occur. This is only one example of the potential risk of species loss that the release of Fusarium Oxysporyum would bring about. Once released into the environment, the fungus can mutate and migrate widely and there is no known control. Colombia’s Upper Putumayo region is just over the border from Ecuador and upriver from Brazil and Peru. One of the chief complaints of Colombia’s neighboring nations is that the fungus - like U.S. foreign policy - does not respect borders or political sovereignty. Wind and water can carry the fungus far from where it was intended, so laws which prohibit its use in Ecuador or Peru are unlikely to be effective. Aside from traveling by wind and water, the fungus can travel on the clothes of those who handle it. As Plan Colombia develops, the people who handle the fungus may well be U.S. soldiers flying out of the Ecuadorian military base at Manta. Manta, on the Pacific Coast, is hundreds of miles from the Putumayo, in another rare and delicate ecological niche known as neo-tropical dry forest. On July 18 Ecuador’s Minister of the Environment Rodolfo Rendón declared that he would not permit Fusarium Oxysporyum to be tested or used in Ecuador, and promised to contact other Amazonian Environment Ministers to discuss regional concerns. On August 14, Ecuador passed a law banning the introduction of Fusarium Oxysporyum. While these are crucial steps in opposing the introduction of the fungus, U.S. Drugwar legislation still threatens both the ecological and social balance of the region. The Airbase at Manta On December 12, 1999 the Ecuadorian Minister of Exterior Relations, under the authority of President Jamil Mahuad, signed a convention giving the United States Military legal rights to use the airbase at Manta as the center of local operations. Six weeks later Mahuad was deposed by a popular uprising and exiled in the U.S., but this highly contested convention still stands as law. The base at Manta is at the heart of what many Ecuadorians see as a U.S. attack on their nation’s sovereignty, and a set of policies which may sooner than later pit Ecuador against its Colombian neighbor. Since early 1999, the War on Drugs has suffered a major setback. Until last year, Howard Air Base in Panama was the center of U.S. anti-drug activity in Latin America. Two thousand surveillance flights left Howard every year until May 1999, when the U.S. was forced to abandon the base as part of the pull-out required by the Panama Canal Treaty. This shift caused the U.S. to begin the search for a new base of operations. With the third candidate, Venezuela, flatly rejecting the establishment of a base within its territory, the most promising sites are El Salvador and Ecuador. But, according to Ecuadorian critics of the plan, the establishment of a U.S. base at Manta is not merely an insult to national sovereignty, it is unconstitutional as well. Doctor Julio Vallejo Prado, ex-Chancellor of Ecuador and an expert in constitutional law, speaking at the July 24 conference at the Centro internacional de estudios superiores de comunicacion para America Latina (CIESPAL) in Quito, “this convention has been inscribed in Ecuadorian law, but it has no base in law because it was agreed to directly between ex-president Mahuad and the U.S.” In other words, Ecuadorian law dictates that international conventions must be submitted to, and ratified by, the congress of the nation. The use of the Manta airbase was given without any such congressional authority. Doctor Prado, clearly indignant at this breach of constitutional law and national pride, elucidated the problem. According to the convention, up to 430 U.S. soldiers can enter the base at any time, by air, sea or land. Doctor Prado notes, “They don’t need a passport, they don’t need a visa. They only have to give notification, once they are here, that they have arrived, and to notify the military authorities of their name and their age. Nothing more.” “We cannot impede their entrance. The only thing we can do is receive the news that they have arrived and a list of their names.” Beyond the use of the base, the U.S. has put certain restrictions on Ecuadorian interference in U.S. military affairs in the zone, including the designation of a restricted area at Manta where not even Ecuadorian military are permitted to enter. A second convention, signed on July 2 of this year between the military authorities in Guayaquil, Ecuador and the U.S. Southern Command, gives the U.S. armed forces the right to detain any Ecuadorian citizen inside the base for any reason whatsoever. Doctor Prado continues, “Once detained in the base, this Ecuadorian citizen will stay detained during the process of investigation. Once the process of investigation is complete, the individual will be returned to the military authorities of Ecuador. This totally violates the principles of sovereignty of the country. There is no judicial process - simply the right to capture and detain any individual, maintain him for the length of the investigative process - whether it be days, weeks, or months - and, after this process, deliver him to military authorities.” The future use of the base at Manta is uncertain. No one outside of U.S. military and government has any idea whether the base will be used for surveillance, interception, or to direct U.S. operations inside Colombia. But what is certain is that the nation of Ecuador, until now considered an island of peace in a sea of violence, is being drawn into a regional conflict against the will of its citizens and beyond the control of its government. From the impending refugee crisis, pesticide drift from fumigations over the Putumayo, and the potential of ecological havoc caused by the release of Fusarium Oxysporum in the Amazon basin, the future of Ecuador, and of the whole Andean region, seems to be in the hands of global free trade policy and the U.S. War on Drugs. Jeff Conant is a writer and activist based in the SF Bay Area, and has published articles, poetry and stories in a variety of magazines and journals. He lived for several years in Chiapas, Mexico, until being expelled from the country along with eleven other foreigners in April 1998 as part of the Mexican government’s campaign against human rights workers. Since then he has been involved in public art projects in the Bay Area. North Atlantic Books recently published his translation (from Spanish) of a book on contemporary Mayan medicine, entitled Wind in the Blood: Mayan Healing and Chinese Medicine. He is currently working for the Hesperian Foundation, publishers of Where There Is No Doctor, coordinating the production of a manual about environmental health. He is also working on a book about the communiques of Subcomandante Marcos, to be titled The Poetics of Resistance.