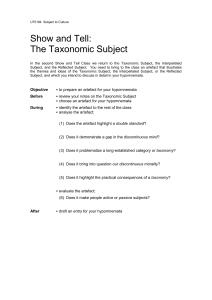

scriptie E Mogulkoc

advertisement