TaylorCapstone

advertisement

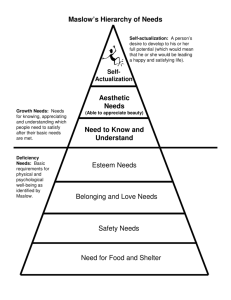

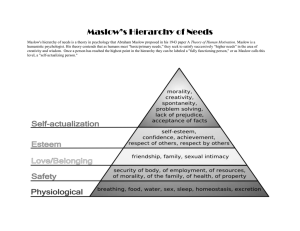

Running head: SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS Serving Students in Diverse Classrooms Non-Licensure Capstone Kimberly Taylor Vanderbilt University 1 SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 2 Abstract Like all people, adolescent members of racial, linguistic, and socio-economic class minorities are in possession of norms and values from their home cultures that influence how they see and act in the world. Unlike those of members of the racial, linguistic, and class majority groups in America, these norms and values often preclude these students from full participation in the classroom culture. Considering racial, linguistic, and class minority students through the theoretical lenses of Lisa Delpit (“culture of power”), Luis Moll (“funds of knowledge”), and Abraham Maslow (Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs) can allow teachers to understand better the interactions between these students’ home cultures and the classroom culture and guide teachers in the creation of strategies for overcoming the barriers or gaps to participation that may arise out of these interactions. Considering through each lens three hypothetical student cases that represent typical, not actual, students in the city of Memphis, Tennessee, the author conducts a conceptual study of racial, linguistic, and class minority students and the aforementioned theories, applying each theory systematically to the cases. SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 3 Introduction In Peabody’s non-licensure capstone programs, professors make no qualms about the fact that students will not get a great deal of practical knowledge and that the readings and discussions that will shape the bulk of the thinking that students do in their courses will be heavily theoretical in nature. Even those students who enjoy the exploration of theory and trust in the abilities of researchers and thinkers to keep the realities of education and the classroom in focus as they write at some point in their programs find themselves, as they should, anxious to get to the application of the ideas that they have explored. As I considered the most effective way to complete my Capstone experience, I realized that there was a way to both meet the expectation that I demonstrate my knowledge of seminal texts and ideas pertaining to education today and also begin the journey toward sating my own thirst to test the mettle of some of these ideas against my past and future classroom experiences. This method is a variant of Ernest Boyer’s “scholarship of application,” specifically, the systematic application of research, theory, and conceptual thinking to concrete questions of practice. For me, the central and most challenging questions of practice are questions of student diversity, especially those of language, class, and race. Over the past several decades, significant scholarly inquiry related to student diversity has broadened and deepened our understanding of the impact of student diversity on teaching and learning; however, that inquiry has not altered practice across the board. This is in part because the research, theory, and conceptual inquiry are not framed from the practitioner’s point of view or from the practitioner’s need. My method here seeks to remedy this. Specifically, I offer a systematic consideration of three hypothetical but grounded profiles SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 4 of urban students, using the work of scholars to illuminate and highlight the potentially constructive response of their teachers. The profiles and scenarios I investigate here are hypothetical, but typical. Each profile represents not an actual student but a typical student, constructed based upon real students in real classrooms in which I, or teachers that I know, have taught. That this study is applied does not make it any less scholarly since I will pursue my consideration of these case studies systematically. That this study is conceptual rather than empirical does not make it any less useful; as educational psychologist Kurt Lewin reminds us, “There is nothing more practical than a good theory.” The method described above has been employed by education researcher Barbara Stengel, who, in her 1991 text Just Education: The Right to Education in Context and Conversation, uses this method to solidly connect sophisticated theoretical ideas to practice. As suggested above, the method will provide an opportunity to explore theories and research in a way that allows both the theories and my past and potential real world classroom experiences to be enriched by each other. The first of the conceptual lenses through which I will analyze each student scenario is the “culture of power” and thereof, its code. In “The Silenced Dialogue: Power and Pedagogy in Educating Other People’s Children,” Lisa Delpit discusses codes of power as the ways of speaking, communicating, and presenting oneself that are viewed as markers of intelligence and/or worth in various contexts (2006). In the context of education, teachers generally expect that, through their parents, students have adapted ways of being that fit well with the norms of the classroom; however, many students in America’s public schools are born into cultures that, out of tradition or necessity, SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 5 promote different ways of being, some of which are in direct opposition to the norms of the classroom. In the case of each student, I will explore how Delpit’s idea of the culture of power and the codes, or rules, thereof can be illuminated for students who by dint of birth or circumstance do not enter school with the cultural knowledge necessary for success in that specific environment. I will also consider each scenario through Luis Moll’s concept of “funds of knowledge.” Moll contends that all students arrive at school with understandings and expertise that they have developed as members of their families and social communities (González, Moll, Amanti, 2005). It is to the benefit of all members of the classroom that teachers make this knowledge apparent and treat it as valuable whenever possible. These experiences are unique not only to the students’ respective cultures in the larger sense of the “culture” but also to the ways of being that are developed as they live in specific locations. Through this lens, I will discuss ways in which teachers can harness these experiences and use them to create meaningful learning experiences for students. I will also consider the ways in which teachers can employ Moll’s strategies for strengthening the connection between the school and the larger community, thereby decreasing the likelihood of cultural clashes as students travel between the two arenas. The final lens through which I will analyze each student’s case is Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In 1943, Abraham Maslow, a behavioral psychologist, developed a human need theory that has since served as a foundation for studies of human motivation in many fields, including Education, Sociology, and Psychology. Maslow asserts that, regardless of group or individual differences, people have a set of core common needs, and these needs can be grouped. These groups exist along a tiered continuum with needs SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 6 toward the bottom of the continuum invariably taking precedence over needs at the top of the continuum. Maslow further contends that unmet needs along this continuum are the greatest motivators of human behavior, dictating what we do or neglect to do in various contexts. Using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a guide, I will consider need-based motivations for each student’s stance on learning and school and explore ideas that language arts teachers of the described students might consider as they create academic tasks that provide ways for students to satisfy their unmet needs. The student cases are as follows. As hypothetical cases, none of these students represent actual students in my experience; however, each represents a student that any teacher might meet in a host of school districts around the country. For purposes of concrete representation, I have located each student in a district that I know well, Memphis, Tennessee, but teachers in any school district might encounter an Aaron, an Amy, and an Alicia. Teachers will likely be better equipped to respond constructively to such students if they can see them through the lenses of Delpit, Moll and Maslow. Aaron Aaron is a Black 15-year-old tenth-grader at a high school in North Memphis, Tennessee. He lives in a two-parent, single-income home where his father works and his mother cares for Aaron and his younger sister at home, picking up jobs sporadically when the family is in need. The money that Aaron’s father earns yearly places the family well above the poverty threshold for a family of four and makes Aaron and his sister ineligible for free and reduced lunch status at the neighborhood schools that they attend. This places Aaron and his sister in the minority of students at these schools. Aaron is typically developing and has never been identified for special education of any kind. In SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 7 elementary school, he demonstrated an eagerness to learn, especially in the areas of English and Science, earning academic awards, joining the Beta Club, and being recognized for good citizenship. His grades were consistently A’s and B’s. In middle school, while his grades did not drop, Aaron participated less in scholarly extracurricular activities, becoming more interested in playing sports with his male peers. Though he still demonstrated proficiency in his classes and on annual tests, it was clear that something had gotten in the way of his once strong interest in academics. Now in high school, Aaron is the back-up point guard on the school’s basketball team and a mediocre student, earning mostly B’s and C’s, and having passable results on the Tennessee Comprehensive Assessment Program Achievement Test (TCAP). When asked about school, he says, “School is a way to play ball, and it’s what I’m supposed to be doing while my dad is at work. I mean, I like some of my classes especially English, but I can’t be walking around talking like no White person, looking like a lame with a bunch of books in my hands.” Aaron’s English teacher remarks that he usually demonstrates content mastery in his work, but she is disappointed and confused by his vehement refusal to perform and engage to the level of which he is capable, specifically, his use of Black Vernacular English in “settings that require more formal language.” Amy Amy is a White 13-year old eighth grade student at a junior high school in Memphis, Tennessee. She lives in a government-housing project in East Memphis with her mother, grandmother, older sister, and newborn nephew. The family has no working adults and receives government assistance for food and monthly child- and healthcare expenses as well as housing costs. Amy’s father is not in contact with the family and SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 8 provides no financial support for his daughters. Amy’s grandmother is an insulindependent diabetic who depends upon her daughter and granddaughters for daily care. Amy has never been a stellar student. Her elementary school teachers would describe her as more outgoing than studious. While she was very rarely unruly in elementary school, her teachers frequently complained that Amy’s behavior was much more womanly than it should have been at that time in her life. She paid more attention to the way that she looked and who might be looking at her than to the task of school. As she grew, this behavior continued and manifested itself in mildly inappropriate relationships with male peers and apathy toward her role as a student. While Amy does not dislike school, she is unconvinced of her belonging there and what school means for her future. Her mother, who does not have a high school diploma or GED, tries to support Amy’s teachers in helping Amy succeed by “staying out of their way and helping her get her lesson at home, if I can understand it.” Amy is currently enrolled in the standard level of her classes and usually makes passing grades, though she is roughly one year behind her classmates, most noticeably in English and Math. To her delight and surprise, Amy began the eighth grade in the same school in which she finished her seventh-grade year, making her a familiar face to the school’s teachers, who attribute her lag to her frequently relocating in school years past and “her mother’s apparent disinterest in her academic success.” Alicia Alicia is an 18-year-old about to begin her senior year at a suburban high school in Memphis, Tennessee. She is first-generation Mexican-American, the only child of two former migrant workers. Just before Alicia was born, her parents were approved for 9 SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS American citizenship and settled in their current location with two of Alicia’s uncles and their wives and children. Over the years, Alicia’s family’s financial situation has improved greatly. Her parents and their siblings own a retail business in the area as well as several homes in which the families live. Though Alicia has no siblings, she is very close to her cousins, who are all Mexican born. She sees them everyday, some of them at school and others at home, as their homes are very close to one another. Alicia is a generally successful student who enjoys school. She is quiet and reserved and, despite being raised in a Spanish-only home, she never had English proficiency issues. Alicia is a voracious reader and has excelled throughout her academic career in English Language Arts, though many of her teachers would say that she lacks confidence in her abilities. This view of her is especially prevalent amongst teachers of classes in which there is a performance or communication component, as Alicia is often reticent to perform and likes to observe for a longer period of time and in a less contributive way than her teachers prefer. Due to these issues, some of her teachers wonder if she has the maturity and initiative necessary for college. Codes of Power In the classrooms of Aaron, Amy, and Alicia, there are rules and expectations. Stated rules, such as, “Turn in all homework assignments at the beginning of class,” are in place to facilitate the business of school and to keep students aware of that which is expected of them on a daily basis. Unstated expectations, such as the expectation that students demonstrate concentration through upright posture and complete silence, serve to communicate and reinforce ideas of that which is proper or normal for effective participation in the classroom culture. Stances on that which is proper and normal for SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 10 schools are usually designated by individuals who belong to or have learned to operate effectively within the “culture of power” (Delpit, 2006). Since the culture of power is mostly comprised of White, middle-class, and upper middle-class people, the norms and values that are prized and communicated within the classroom most closely resemble the norms and values of White, middle-class, and upper middle-class society (Delpit, 2006). This means that students who have been fed these values from birth are likely to perform well in school because they enter the classroom with cultural capital, or understandings of discourse patterns and styles of behavior, that allow them to participate effectively within the culture of power. According to Delpit, students without this cultural capital, usually children from non-White, non-middle-class families or communities, find themselves at a disadvantage not only because they lack the aforementioned understandings, but also because many of the rules for participation in the culture of power within the classroom are not made apparent to them (2006). While students who lack cultural capital are likely aware that there is a power culture within the classroom and that they are in some way outside of that culture, they are often unaware of what it takes to become participants. These students need guidance to recognize and understand both the surface features of interactions within the culture of power and the sociopolitical underpinnings of those interactions. Guidance comes from the arbiters of power, or power brokers, within the classroom, their teachers (Delpit, 2006). It is imperative that teachers fully accept their roles as power brokers and operate within this position of authority to the extent that is necessitated by their students’ membership in the culture of power (Delpit, 2006). This means, among other things, being careful to explicitly educate students outside of the culture of power about the rules SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 11 and values that exist within the culture of power before employing across the board instructional strategies that place the onus of cultural competence solely upon the student (Delpit, 2006). Operating effectively within their positions of power also requires teachers to reinforce to students the value of their home cultures, helping them to create bridges between their home and school worlds. For this to be done well, the parents and teachers who share cultures with disenfranchised students must be legitimately welcomed into conversations with teachers and other school personnel about that which best serves their children in school (Delpit, 2006). Through these efforts, Delpit contends that teachers can assist students in developing and recognizing their own “expertness” and “help students establish their own voices…” and “…coach those voices to produce notes that will be heard clearly in the larger society.” (2006, p.46) Funds of Knowledge Aaron, Amy, and Alicia are members of networks that extend beyond the classroom. These networks give them access to different forms of knowledge that can be accessed and utilized for instruction in unconventional ways. Gonzáles, Moll, & Amanti argue that the acquisition of knowledge is not just a hallmark of classroom instruction, but takes place in various social, ideological, political, and familial arena of students’ lives (2005). These networks of knowledge are often unknown to instructors and school officials, and thus are not used as tools for instruction. Gonzáles et al. refer to gains from the areas as “funds of knowledge,” relevant knowledge gained from life experience (2005). Instructors are encouraged to tap into this existing knowledge and use it to influence literacy instruction strategies in classrooms. Funds of knowledge represent an additional tool in the instructors’ kits, a ready-made set of resources that can be used SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 12 not only to bridge home culture and class culture, but also to show that students’ home lives and the knowledge gained from their interactions there are valuable as well. Recognizing, gathering, and using funds of knowledge in classrooms can also assist teachers in bridging gaps created by social and class differences among students and teachers. According to Gonzáles et al., instructors’ exhibiting to students that their exterior knowledge has value and is useful in the classroom creates the basis for meaningful relationships between students, instructors, and families, and also creates new dynamics of power in the classroom (2005). Being an educational model, the ultimate goal of the funds of knowledge framework is to empower students in the classroom; however, a feature of the model that is tantamount to this is empowering parents of children who are class, language, or racial minorities by acknowledging that they have numerous skills and talents that they expose their children to and that through this exposure they make important contributions to their children’s academic and social success. When parents are made aware that knowledge or skills with which they are familiar are being addressed in class, they are empowered to make contributions to their children’s learning experiences (Hensley, 2005). According to Hensley, children and their parents reap additional benefits when they see “a parent bring a new avenue of learning into the classroom.” (2005, p.145). Increases in selfesteem, self worth, and feelings of empowerment to have a positive impact on their children’s academic lives can make these parents more likely to involve themselves in school efforts that usually experience poor parent participation (Hensley, 2005). SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 13 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Students, like all people, have needs of varying intensities, and the status of those needs, whether they are met or unmet, drive their behavior and the decisions that they make. These needs, also known as motivators, were studied extensively by Abraham Maslow, who in 1943 posited a theory of human motivation in which he arranged the most universal of human needs into five clusters that were then placed into a pyramidal grouping according to the priority of their fulfillment. According to Maslow, the most basic needs are the ones that are of highest priority to fulfill and are located at the base of the “need hierarchy,” while the needs toward the top level of the hierarchy are met through more intangible means and will likely go unsatisfied until needs at the lower levels are fulfilled (1943, p.15). The hierarchy includes the most basic to the most complex of the universal needs and is described below. As mentioned above, the need category type at the base of the hierarchy is the physiological need category. Physiological needs are met by ensuring sufficient function of the body. Meeting these needs is necessary for survival, and includes acquiring food, air, and water. Physiological needs outweigh other needs. For example, a student who is hungry will be more driven to acquire food than they are to engage in classroom exercises that build community and allow for creativity because, since the needs for a sense of community and opportunities to express creativity are located at higher levels in the hierarchy, they are “…simply non-existent or…pushed into the background.” (Maslow, 1943, p.16). Clothing and sleep are also included in this category. The next set of needs in the hierarchy is that of safety and security. Consciousness of wellbeing is important and in the absence of different levels of safety, people can SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 14 develop stress-related disorders that take physical and emotional tolls (Maslow, 1943). Security needs include physical safety, health, job security, and systems of familiarity. Children tend to react strongly and quickly to perceived unsafe stimuli in their environments and will cling to parents or other familiar symbols of safety when their wellbeing is threatened (Maslow, 1943). As people become older they are more likely to inhibit their reactions to the lack of safety in their lives (Maslow, 1943). After safety needs are met, needs for belonging arise. Belonging is a social need tied to inclusion and is called “the love need” by Maslow (1943, p.20). People at this level of the hierarchy “will hunger for affectionate relations with people in general, namely, for a place in [the] group, and…will strive with great intensity to achieve this goal.” (Maslow, 1943, p.21). Similar to the case of safety and security needs, children, who are generally quicker than adults to form emotionally significant relationships, will outwardly demonstrate more intensity than typical adults in their efforts to achieve belonging and maintain membership in social groups (Maslow, 1943). The next need category is self-esteem and is fulfilled when the individual is assured of his or her value based on achievement, accomplishment, and the respect of others (Maslow, 1943). According to Maslow, basic self-confidence is necessary, and without it, people are helpless (1943). The process of gaining self-esteem involves attaining strength, building a sense of achievement and adequacy, and realizing one’s desire for prestige, recognition, and appreciation. Since school is both a social and an academic endeavor, it is an ideal environment for cultivating the above characteristics in children and young adults. SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 15 The topmost need in the hierarchy is the need for self-actualization or understanding and acceptance of one’s purpose and potential. In Maslow’s words, “What a man can be, he must be” (Maslow, 1943, p. 22), and to this end, the man must strive to know himself and his capabilities. People, according to Maslow, ultimately desire to be true to their natures and, in the absence of motivations related to unmet needs on lower levels, will strive mightily to satisfy the desire to reach the heights of their potentials. The concept of self- actualization is broad, and methods of attainment vary by individual; however, in all cases, self-actualization can only be attained by an individual whose physiological, safety, association, and self-esteem needs are fulfilled (Maslow, 1943). Needless to say, the achievement of this level on the hierarchy is a lifelong and deeply personal process. Still, teachers of adolescents can aid students in attainment by helping them to understand their lower level needs and guiding them, to the extent possible through school-based tasks, toward meeting those needs. Aaron Through the Lenses Aaron’s most significant barrier to participation in the culture of power in the classroom is his use of Black Vernacular English, his home language, rather than Mainstream English, the linguistic power code of the school. More accurately, it is his inability or unwillingness to switch between the two codes depending upon the context, audience, and purpose of his speech interactions. This context-based exchange of dialects or languages is called code-switching and can only be effectively performed if the speaker is an adept user of both dialect or language options (DeBose, 1992). In order to assist students like Aaron in becoming adept at using the power code, teachers must first assure students that their home language is valued in the classroom and that the SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 16 teacher, the power broker in the classroom, does not view the code as deficient or inferior to the power code. In her 2002 work, The Skin That We Speak, Lisa Delpit describes this as reducing students’ affective filters and gaining their trust so that they might “…be willing to adopt our language form as one to be added to their own.” (p.48). In order to gain the necessary knowledge of the students’ home language, teachers can follow Moll’s example and look into students’ homes and/or communities to find social patterns and knowledge that might be helpful in teaching relevant classroom concepts (Gonzáles et al, 2005). By connecting these classroom concepts to their home lives and communities, teachers make the concepts socially meaningful for students (Gonzáles et al, 2005). For example, Aaron’s teacher might observe an exchange between Aaron and one of his teammates, and later ask Aaron to recall and analyze the effectiveness and appropriateness of his language in that exchange in terms of the purpose, audience, and context. The teacher could then ask Aaron to consider the ways in which the conversation could or should change if one of those points of analysis were to change. In addition to bringing to bear the knowledge of appropriate language use that the student already has, this exercise challenges Aaron to practice decoding input and using the information to pursue a specific course of action. While validating the home code and making the complexity of its use apparent to students, teachers can frame mainstream English, not as a replacement for the home code, but as an addition to the students’ social and academic skills sets, taking an additive rather than subtractive approach to language acquisition (Trumbull and Pachecho, 2005). While it is imperative to make clear to students the implications for using or not using mainstream English in certain contexts, it is equally important to allow students to form SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 17 and discuss their own ideas about what each code means in their lives. Teachers should recognize that one very important feature of a person’s home language is its function as a means of satisfying that person’s need for association, love, and belonging, which is paramount after physiological and safety needs are met (Maslow, 1943). Seeing Aaron’s home language in this light, a teacher might be more likely to engage Aaron in frank conversation about the importance of being able to communicate across cultural groups and the benefits of belonging to more than one community of people, the goal being ultimately to help Aaron to see that there is no dichotomy between membership in the culture of power and membership in his home culture. Amy Through the Lenses Due to her mother’s low socio-economic status, high levels of stress associated with being an at-home caregiver, and low literacy, Amy’s lack of participation in the culture of power can be reasonably attributed to her mother’s not having sufficient time and/or knowledge to impress upon Amy the values and norms of the culture of power in schools (Lareau, 2011). Of the aforementioned factors, Amy’s mother’s low literacy is the most likely to lead to feelings of disassociation and disempowerment in the school setting (Lareau, 2011). This requires that the teacher in this case go beyond making effective participation in culture of power apparent to child and work to make said participation apparent to the parent. One large hurdle for Amy’s teacher to overcome is the assumption that Amy’s mother understands the business of school and simply does not care to be a participant. Instead of assuming, the teacher should work to begin a partnership with Amy’s mother, making apparent to the mother that she and the school have a joint concern and obligation to Amy and that both parties are in possession of SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 18 ingredients necessary for Amy’s success (Epstein, 1995). A step in this direction could be having a conversation about what schools expect of parents and what parents should expect of schools. Such information might be provided through an email or packet with meeting options, via phone call, or in a home visit. Teachers should be creative and thorough in their efforts to communicate such pertinent information. Teachers with families like Amy’s represented in their classrooms could further nurture welcoming relationships between parents and the school by giving the parents concrete strategies and opportunities for participating in the school culture in ways that benefit their children. Like many children, regardless of their parents’ understandings of the business of school, Amy is not yet a student who can appreciate learning for its own sake. Therefore, her teacher would do well to employ Moll's strategy of creating lessons that allow students to discover knowledge within the context socially meaningful tasks (Gonzáles et al, 2005). A teacher who has made the effort to learn about Amy’s role in caring for her grandmother might be able to encourage Amy to practice expository writing, a skill that is assessed by the state of Tennessee during a student’s eighth grade year, by making apparent to Amy her unique expertise as a caregiver. With guidance, and using this knowledge and experience as a base, Amy could become familiar with the purposes and features of effective expository writing and eventually begin to apply these techniques to writing about less socially significant topics for academic purposes. Once familiarized with Amy’s role in the home and her living circumstance, the teacher must recognize that Amy may have unmet physiological, safety, or security needs (Maslow, 1943), acknowledge the probable impact of those unmet needs on Amy’s motivation to participate in school, and work to counteract those impacts. One way of SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 19 counteracting these effects is to help Amy become aware of and empowered by her ability to change her life through her role as a student and require that Amy do all that she can to take advantage of her school experience. To do this, the teacher must be what Gloria Ladson-Billings in her article “The Power of Pedagogy: Does Teaching Matter?” calls “warmly demanding,” able to show empathy for students whose life circumstances may be harsh while not lowering expectations of academic success for those students, making excuses for them, or allowing them to make excuses for themselves (2001). Alicia Through the Lenses For Alicia’s teacher, explicitly educating Alicia on the rules and values of the culture of power might mean having a direct, age-appropriate conversation about the classroom as a setting in which she as a student is expected to develop as a autonomous thinker who is capable of defining her views and self without unnecessary influence from others (Delpit, 2006). The teacher would do well to know that due to stereotyped roles of masculinity and femininity common amongst Latino populations, Alicia may struggle with how to demonstrate the behavior that her family and community designate as appropriate for girls and women while still asserting herself and pushing forward her ideas in the way that is expected of her at school (Griggs and Dunn, 1995). It might also benefit her teacher to know that studies have found that students raised with values and norms common in Latino communities are less likely to be comfortable with learning exercises like peer review as such lessons are trial-and-error oriented and have fewer instances of adult modeling (Griggs and Dunn, 1995). By being familiar with Alicia’s cultural norms, the teacher may be able to make apparent to Alicia the nature of some of her barriers to participation with the culture of power and help her begin the journey to SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 20 reconciling issues arising from interactions between her home culture and the school culture. Since Alicia has never demonstrated issues with English language proficiency, her teachers might be unaware that she is speaks only Spanish at home and has been raised participating in both Mexican and American cultures. This means that her biculturalism and bilingualism are untapped resources that teachers can use to broaden Alicia’s learning experience (Gonzáles et al, 2005). A teacher who inquires into Alicia’s home literacy practices might find that her mother is fully literate in Spanish and that Alicia and her mother have always bonded through sharing and discussing Spanishlanguage books and stories. A teacher could tap into this facet of Alicia's home life by allowing her to create a project in which she shares some culturally specific stories from her childhood and analyzes the purposes and features of these stories in juxtaposition to some well-known American children's stories. Exercises like these that build upon both her Spanish and English language skills could help Alicia to have a deeper, more authentic grasp of literacy in both languages and improve her ability to use both languages to interact more effectively across cultures. The above described exercise could improve Alicia’s confidence as a participant in the information exchange happening in her classrooms by making apparent to her some of her own expertise. They are also opportunities for Alicia to see that by participating fully in both her home and school cultures she can become a more complete version of herself than she could have become by having only one set of experiences. These kinds of realizations can equip Alicia to move beyond the comfort of having her needs for association fulfilled to working toward fulfilling her self-esteem SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 21 needs, which are met when one is able to see oneself as a person with unique experiences and knowledge that are worthy of being valued and respected by others (Maslow, 1943). Summary and Conclusion In constructing hypothetical student cases and analyzing them according to theories by Delpit, Moll, and Maslow, I have attempted to demonstrate the ways in which educational concepts that are usually explored in abstraction can be applied to concrete representations of reality to illuminate classroom practice and deepen theoretical understandings. Viewing each student’s case through the lens of Delpit’s theory of the culture of power allows practitioners to better understand the ways in which schools are structured and how that structure bolsters or impedes academic and social progress for certain groups of students dependent upon how the home norms and values of these students interact with the school structure. Moll’s model provides a means by which to use students’ home knowledge to empower both students and parents while giving the teacher more tools for taking students beyond their current knowledge to new understandings and ideas. By considering each student as Moll does, as a complete person with a viable set of experiences, knowledge, and expertise, teachers open themselves to the possibility of becoming partners in the teaching and learning process with students and their parents. My analysis of each case through the lens of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is not an attempt to answer the hotly debated question of whether or not it is within the obligations or abilities of the school to help students address those needs. Rather, it is an effort to acknowledge the fact that the status of a student’s needs, whether they are met or SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS unmet, is manifested in the student’s academic performance and school behavior. Further, I aim to begin the difficult task of exploring strategies for assisting students in gaining the skills and understandings necessary for meeting their own needs without detracting from the academic focus of the classroom. My hope for myself and for my fellow teachers is that we reach new understandings of our roles, our students, and the school structure by viewing them through these lenses, and use those new understandings to restructure our individual classroom cultures to better serve all students regardless of their racial, linguistic, and class differences. 22 SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 23 References Boyer, E. L. (1997). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professorate. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. DeBose, Charles (1992), "Codeswitching: Black English and Standard English in the African-American linguistic repertoire", in Eastman, Carol M (Ed.). Codeswitching (pp. 157–167). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters LTD. Delpit, L. (2002) The skin that we speak: Thoughts on language and culture in the classroom. New York, NY: Norton. Delpit, L. & Dowdy, J. K. (Eds.). (2006). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. New York, NY: Norton. Epstein, J. (1995). School/family/community partnerships: Caring for the children we share. In Jana Noel (Ed.). Classic edition sources: Multicultural education (3rd Ed.), (pp. 192-199). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Gonzáles, N., Moll, L. C. & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Griggs, S. & Dunn, R. (1995). Hispanic-American students and learning style. Emergency librarian, 23(2), 11-17. Hensley, M. (2005). Empowering parents of multicultural backgrounds. In Norma González, Luis C. Moll, & Cathy Amanti (Eds.). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms (pp. 132-143). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. SERVING STUDENTS IN DIVERSE CLASSROOMS 24 Ladson-Billings, G. (2001). The power of pedagogy: Does teaching matter? In Jana Noel (Ed.), Classic edition sources: Multicultural education (3rd Ed.), (pp. 110-115). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life (2nd Ed.). Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. New York, NY: Harper & Row. Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370396. Stengel, B. S. (1991). Just education: The right to education in context and conversation. Chicago, IL: Loyola University Press. Trumbull, E. & Pacheco, M. (2005). Leading with diversity: Cultural competencies for teacher preparation and professional development. Providence, RI. Brown University.