GanzCapstone

advertisement

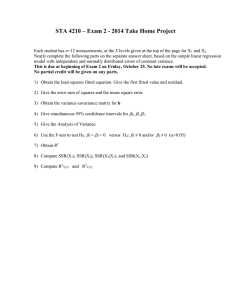

Running head: IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING Implementing Sustained Silent Reading to Produce Gains in Reading Achievement and Reading Attitude Kathryn R. Ganz Vanderbilt University Match 1, 2012 1 IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 2 Abstract Sustained Silent Reading (SSR), an independent voluntary reading program, has been implemented in classrooms for over sixty years, however its effectiveness in improving reading achievement and reading attitude has been challenged by teachers and researchers; most notably, the National Reading Panel (2000). Research studies, metaanalyses, theory, and professional accounts of SSR reviewed in this paper show student gains in both reading achievement and reading attitude, however a consensus on how to design and implement a successful SSR program was an issue throughout the literature. The successfully implemented programs were analyzed to develop recommendations and guidelines for designing and implementing a SSR program appropriate for students in Kindergarten through 12th grade. Findings suggest successful programs provide a quiet, uninterrupted, and comfortable environment, access to books in the classroom, freedom of book selection, teacher modeling and an absence of evaluative activities, with additional options recommended based on student age. IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 3 Too often in education, we focus on accountability, assessment, and skill based instruction; cutting out time for students to authentically practice their skills. In 1971, McCracken recognized the need for the practice of reading stating: “In our press for achievement, the importance of practice in reading silently has been overlooked. Our students are over taught and under practiced” (p.583). Reading, like any developing skill, must be learned, practiced and generalized to a variety of authentic experiences. Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) is a strong method to use in the classroom to help students practice this important skill. To investigate this topic, I have researched the history and development of SSR, theories of learning that support the use of SSR, studies that have evaluated at the effectiveness of SSR in comparison to other practices, teacher and researcher designed models, as well as reviews of the literature on SSR. Through review of these sources I have compiled and compared the successful program designs establishing a set of key factors and guiding principles to consider when creating a SSR program. Based on the studies reporting gains in reading achievement and reading attitude, it is evident that SSR is an effective program when purposefully designed and implemented. For the purpose of this literature review, the term “reading achievement” refers to vocabulary knowledge, reading comprehension, reading accuracy, and fluency. Each program used different measures to establish achievement gains, some focusing on only one of these aspects of achievement, however across the studies these four categories were assessed. The term “reading attitude” refers to a student’s positive or negative feelings about reading as well as his or her motivation to engage in reading. To measure this, students were interviewed about their feelings towards reading in and out of school, feelings about going to the library, concepts of the IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 4 importance of reading as well as measuring the time students spent engaged in reading. This was done both through informal interviews as well as through reading attitude inventories. During my courses this past fall in the Reading Education program, I learned a great deal about different theories and models of reading. After learning about the contradictory findings of the National Reading Panel Report on Fluency, which did not recommend the practice of SSR, I wanted to dig deeper into the concept of independent reading to determine its effects on reading achievement and reading attitude (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000). While in EDUC 3390, I researched the history and effectiveness of SSR, and found there to be large variations in the designs of models used in studies. Because of the variation, it is difficult to compare studies without knowing if the inclusion or exclusion of certain factors affects the overall success of SSR. While my initial research showed that SSR is an effective reading program that increases reading attitude and reading achievement, the extension included in this paper provides research-based recommendations for effective implementation. To make these recommendations I have revisited studies, teacher implemented programs, and metaanalyses of SSR to categorize factors included in the various models. The History and Development of Sustained Silent Reading SSR and similar models of silent independent reading have been studied and implemented for over sixty years (Pilgreen, 2000, Forward by Krashen). McCracken (1971) developed one of the earliest models of SSR based on the 1960s Uninterrupted Sustained Silent Reading (USSR), developed by Dr. Lyman C. Hunt, Jr., Professor at the University of Vermont. This program’s goal was to meet the objective of developing a student’s ability to read silently without any interruption for a long period of time. Shortly after, in the 1970s, Robert McCracken IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 5 took away the U, and changed the acronym to SSR in order to decrease the negative attention the name was commanding. McCracken’s model held the same objective as Hunt’s. He defined SSR as “the drill of silent reading” (1971, p.521), going on to say that it should be considered the practice of reading and not the complete reading program. This concept will be revisited later in the paper. For effective initiation of this model, McCracken (1971) presents six guidelines: 1. Each student must read silently. 2. The teacher models by reading silently at the same time, and does not allow for interruptions. 3. The students select one text and reads for the entire time. 4. A timer is set so that students do not watch the clock. 5. Students do not have to keep records or report on their reading. 6. Starting out with larger groups is most effective (p.522) Following these guidelines, McCracken (1971) found that a sustained power of reading could be achieved almost immediately. After six months of practice in SSR, his research showed that the students made gains in reading achievement as well as reading attitude (p.582). Since these early studies of SSR, many different names and models have been created in order to increase student reading and see gains in student achievement and attitude as McCracken did. Additional sustained silent reading programs include: Free Voluntary Reading (FVR), High Intensity Practice (HIP), Sustained Quiet Reading Time (SQUIRT), Positive Outcomes While Enjoying Reading (POWER), Fun Reading Every Day (FRED), Drop Everything and Read (DEAR), Daily Independent Reading Time (DIRT), and Motivation in IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 6 Middle School (MIMS) (DeBenedicts, 2007; Pilgreen, 2000, p.1). For the purpose of this literature review, I will refer to the practice as SSR. Since the original claims of student reading growth due to SSR, research has been conducted on the program in comparison to skills based instruction. In 2000, a National Reading Panel was formed to complete a report on the five main areas of literacy, which included phonemic awareness, phonics, oral reading fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Within the fluency subgroup, the panel conducted a metaanalysis of fourteen studies fitting specific criteria, and concluded that the research did not support SSR as a statistically significant model to use in school (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services et al., 2000). This finding surprised many teachers, principals and researchers, creating a need to trace the rationale for removing SSR from classroom practices. With this need, skeptics often met difficulty in finding answers to questions as they were continually passed to higher establishments (Edmondson & Shannon, 2002, p. 453). That same year, Pilgreen (2000) wrote The Handbook for SSR, reevaluating SSR with two goals in mind. First, to increase reading achievement, and second, to increase reading attitude, just as McCracken (1971) had done in the 70s. Pilgreen’s (2000) model is commonly cited when discussing, implementing, and researching SSR as well as other variations of the model. For this reason, it is important to identify the eight factors that make up Pilgreen’s SSR model. 1. Access: Students should have access to a vide variety and selection of reading materials, including magazines, newspapers, books, comics and other reading materials. 2. Appeal: Reading materials should be interesting to the students, and students should select the materials that they want to read. 3. Conducive Environment: SSR should occur in a comfortable, quiet and uninterrupted place. IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 7 4. Encouragement: Teachers should encourage students to read through modeling good reading practices, being involved in sharing and discussing books, acting as a resource for book selection, involving a child’s home with the SSR practices. Staff, administration and parents can also provide these kinds of encouragement. 5. Staff Training: School staff should be trained in SSR so that they can also participate in modeling and encouragement. 6. Nonaccountability: No reports or records of books read should be kept. The focus should be on pleasure reading rather than assessment. 7. Follow up Activities: After reading students can be encouraged to share in interactive ways with peers or the whole class. 8. Distributed Time to Read: Ideally, students will have SSR daily, but it should at least occur twice a week for 15 to 30 minutes (pp. 32-36). Acquiring information from studies as well as classroom experience, teachers and researchers have developed new ways to implement SSR, using many of Pilgreen’s eight factors (Akmal, 2002; Kelley, Clausen-Grace & Nicki, 2006; Reutzel, Johnes, Fawson, & Smith, 2008). The models of SSR employed by many of the studies looked at in this paper follow a similar structure; with the main features typically being nonaccountability, access, encouragement through teacher modeling, and an uninterrupted conducive environment. Theoretical Support for Sustained Silent Reading One reason that SSR has been, and continues to be studied, is the support it receives from many accepted theories of reading. In Goodman’s (1994) transitive sociopsycholinguistic view of reading, he describes learning occurring through authentic uses of language, possessing the perspective that students learn by doing. Adams’ (2004) model of reading includes a meaning IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 8 processor that applies the context in which a word is placed to build an understanding of that word. As readers have more encounters with a word in different contexts they develop a greater comprehension of the word. Supported by research (Nagy, Anderson, & Herman, 1987), Adams attributes much of the vocabulary a person acquires to the amount of reading they do (p.1232). Cunningham and Stanovich (1998) apply the biblical term “Matthew effects” to reading achievement in their article on the importance of reading. This term represents the idea of the rich-get-richer and the poor-get-poorer. When applied to reading, this term means that poor readers read less because of the difficulty they experience when reading and strong readers read more because of their success, ability to comprehend, and enjoyment of the text. Supporting this theory, the National Reading Panel found hundreds of studies reporting extensive correlation between good readers and high amounts of reading and poor readers and low amounts of reading (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services et al., 2000, p. 3-21). In effective instruction, a line can be drawn between theory and practice. Based on these examples of learning theories, SSR has a strong theoretical foundation. The Effects of Sustained Silent Reading on Reading Achievement While theory is important, practice must also be backed by research. Much of the existing research on SSR and similar models have studied the effects of SSR on reading achievement in order to determine a rationale for this type of program. In most of the studies, researchers compared student achievement in word recognition, comprehension and fluency after involvement in an SSR program with students who did not engage in SSR. Overall, the results have been mixed. While many studies report achievement gains (Davis, 1988; Elley, 1992; Holt & O’Tule, 1989; Kornelly & Smith, 1993) other studies did not find that SSR had a statistically significant impact on reading achievement (Cline & Kretke, 1980; Collins, 1980). Despite a lack IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 9 of statistical significance, it is important to note that students involved in SSR often achieved equal amounts of growth, if not more, than students engaged in only traditional reading skill instruction. A possible explanation for the nonstatistically significant results found in two of the studies may be that the students have already approached their ceiling of reading achievement. Davis (1988) looked at both a high ability reading group and a medium ability reading group and found that only the medium ability group showed statistically significant gains. In a similar study to evaluate the long term effects of SSR, Cline and Kretke (1980) reported only slight gains in achievement for the experimental group engaged in SSR, which was made up already high achieving students. Supporting the hypothesis that students nearing their ceiling of reading achievement show smaller gains, Holt and O’Tule (1989) studied the effects of SSR on seventh, and eighth grade student that were reading two years below grade level and found that students engaged in SSR had significant growth in vocabulary, comprehension and reading attitude. The issue of initial reading ability is not a factor that the National Reading Panel (2000) took into account when reviewing the same studies. Cunningham (2001) critiques the National Reading Panel for selecting these studies that tested the effectiveness of SSR without ensuring that the students involved needed treatment to improve reading abilities beyond where they initially were reading (p.333). Given this oversight, the National Reading Panel statement that a schools are not recommended to adopt programs that encourage more reading to improve reading achievement, such as SSR, should be questioned. The Effects of Sustained Silent Reading on Reading Attitude Developing a positive attitude towards reading is important for many reasons. Students who read a variety of materials for pleasure and show positive attitudes towards reading are IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 10 typically better readers regardless of their family background (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2007, p. 15). As we grow and develop, much of what we learn is acquired through reading, and developing a joy for reading at a young age will help students grow into skilled, lifelong readers (Garan, 2008, p. 336). Avid readers can open a book and learn information, experience new places, and imagine different lives. Additionally, there are many competitive forces at play for children’s attention during leisure time, especially in our rapidly advancing technological world. Children must develop motivation through enjoying and value of reading in order to compete with other modes of entertainment such as TV and video games. Many of the studies assessing the effects of SSR on reading achievement also assess its effects on reading attitude. For some of the studies reporting no significant growth in reading achievement, there was a clear significant growth in student attitudes towards reading (Cline & Kretke, 1980). Other studies showed growth in both achievement and attitude (Holt & O’Tule, 1989; Kornelly & Smith, 1993), and further studies looking solely at attitude towards reading found statistically significant results (Chua, 2008; McCracken, 1971; Yoon, 2002). Overall, there is a consensus throughout the research that SSR has a statistically significant positive effect on students’ attitudes about reading. In these studies, students’ increased attitude towards reading was seen through their increased voluntary reading time, greater interest in books they were reading, and the verbal praise they had for reading and for SSR in particular. Cline and Kretke (1980) found that students engaged in SSR felt happier about going to the school library, more positive about reading a book they chose, better about doing assigned reading, and more positive about the importance of reading. Kornelly and Smith (1993) report that some students who claimed to hate IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 11 reading initially, stated that they made time for reading at home after involvement in the USSR program. Chua (2008) found as the year progressed, students became more engaged during the SSR period as reported by themselves and their peers. She also reports that students found reading books more pleasurable and enjoyable at the end of the yearlong program. Summary of the Effects of SSR on Reading Achievement and Reading Attitude All of the studies reviewed reported that engagement in SSR produced as effective, slightly more effective, or significantly more effective results in reading achievement than comparison programs. Even in the cases where only equal or slightly higher academic gains were achieved, the positive results in reading attitude for the students engaged in SSR make it an effective practice overall. In a survey of 1,765 students conducted by Ivey and Broaddus (2001) on which reading activities students enjoyed most in the class, the most common response was free reading time, showing that SSR not only influences a positive reading attitude, but also that students enjoy engaging in it. This is an argument that has been suggested in response to the National Reading Panel conclusion that SSR is not proven to be an effective classroom practice (Krashen, 2001). Issues and Concerns about SSR and Available Research Reviewing the research on SSR, there are clear issues with reliability of the results. One concern is the length of time SSR was implemented for in each study order to draw conclusions. Krashen (2001) notes that the National Reading Panel did not include any studies lasting longer than one year. It is not clear how long the program needs to be implemented to see significant results, however there have been studies that show increased achievement and attitude gains over time (Chua, 2008; DeBenedicts, 2007). Also, the differences in the population of students being IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 12 studied could have had an influence on the results based on their initial reading ability at the start of the SSR program (Davis, 1988; Krashen, 2001). Additional concerns are found when drawing conclusions because of the possibility that the evidence is simply correlational. The National Reading Panel suggested a possible explanation for the correlation between high reading levels and high reading ability is that good readers elect to read more (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services et al., 2000). Because correlation does not equal causation (Paris, 2005), results must be interpreted with caution. Over the past ten years, the findings of The National Reading Panel, which determined the results of their SSR study to be inconclusive based on a lack of statistically significant evidence of reading achievement gains, have been a looming concern. Because of this report, many teachers, principals and parents questioned the use of SSR in schools, while other teachers and researchers refuted the National Reading Panel, as well as the International Reading Association (IRA), which accepted this report, providing counter arguments to the findings (Edmondson & Shannon, 2002; Garan, 2008; Krashen, 2001). In response, Timothy Shanahan (2006), President of the IRA at the time, claimed that he had been misquoted to think that reading is not important for kids. On the contrary, Shanahan has a strong belief in the importance of reading, and reminds those concerned that there was simply not enough evidence to claim that SSR produces higher reading achievement than reading instruction, pointing to the need for further research on this topic. Despite the National Reading Panel conclusion, there is a strong foundation for the importance of spending time engaged in reading. With this knowledge, it is important to address the issue of program design and implementation. Because of the variety of models, and the fact that “classrooms are not IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 13 laboratories” and all conditions cannot be controlled (Garan, 2008, p.337), it is likely that teachers implemented SSR with some variability in these studies. While most of the studies looked at included some of the major factors that make up SSR as defined by Pilgreen (2000), the models were not exactly the same. Some studies included boundaries on student reading materials or had teacher guidance in book selection (Cline & Kretke, 1980, Trudel, 2008). Another study did not specify characteristics of the SSR model implemented (Collins, 1980). Some teachers had issues with following the nonaccountability rule, and found a decline in thoughtfulness of reading, realizing that their students were simply skimming their books for the required amount of time (Lee-Daniels & Murray, 2000). It has also been found that many teachers claim to, but do not actually engage in reading during the SSR period, which is an important modeling aspect of this method (Loh, 2009). There have been many successful cases of modifying SSR to be more meaningful and effective for a specific classroom (Kelley, Clausen-Grace & Nikki, 2006; Reutzel et al. 2008), however, variations on SSR are often due to inconsistent implementation (Loh, 2009). To address some of these concerns I will describe the different ways successful SSR programs have implemented various theoretical and research based practices into their programs with regard to student age and program purpose. Designing and Implementing an Effective Sustained Silent Reading Program As described above, there have been many studies conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of SSR and other independent reading programs, however there are few studies that have evaluated what makes a SSR program effective (Wiesendanger, Braun & Perry, 2009). Because of the inconsistent methods, there is an unclear understanding among teachers about how to effectively implement a SSR program, as Douglas Fisher (2004), a teacher and director of professional development in San Diego, established when interviewing and surveying teachers in IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 14 which he taught. Reviewing SSR studies, teacher designed and implemented programs, teacher interviews, as well as modifications to SSR, I have compiled a list of recommendations for how to establish a SSR program that will promote reading achievement and positive reading attitude in a school setting. In determining these factors, I have selected the most commonly implemented practices used in successful programs. Through analyzing the various programs, I found seven categories to consider: environment, frequency and duration, access to books, book selection, accountability, teacher roles and student roles. For some categories, student age plays a large role in determining effective factors to implement based on developmental needs, while other factors have been successful and important across all age levels. When necessary, recommendations have been divided into Kindergarten through 3rd grade, 4th through 8th grade, and 9th through 12th grade distinctions. Before planning, it is important to establish two things, first; the age group of the students that will be engaged in the program, and second; the desired outcome of the program. As discussed in the first half of this paper, SSR is an effective program that increases student reading achievement as well as reading attitude. Within these two categories, students can develop increased word recognition, comprehension, fluency, as well as motivation to read, enjoyment in reading for pleasure, development of book selection strategies, and self regulation and metacognitive strategies. While engaging in SSR will benefit students in all of these areas, there are certain factors that can be included to focus on some more than others. First, note that in 1971, McCracken insightfully said that SSR should be a part of the reading instruction program, not the whole thing (p. 521). The supporting research that I have found implements SSR as part of the school day in addition to some amount of literacy instruction. In a study evaluating successful recreational reading programs, Wiesendanger et al. IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 15 (2009) interviewed teachers on the aspects of their SSR program that they found to be most important. Of the 90 teachers interviewed, 91% shared the idea that independent reading should be only one aspect of the classroom literacy program, and other skills including decoding and comprehension strategies must be taught as well. Unfortunately, the debate over SSR has been positioned in a way that makes people feel a need to determine if they think the practice is effective or not effective to use in the classroom compared to other instructional strategies. Successful implementation requires teachers to think as McCracken (1971) did, considering SSR to be a part rather than a whole program. Frequency and Duration The SSR time should last for 10-30 minutes, five days a week. The program should start gradually with short amounts of time (1-5 minutes), building to longer amounts of time (Kaisen, 1987; Collins, 1980; Anderson, 2002; Collins, 1980). The full length of the daily SSR time will depend on the teacher’s individual students. To determine the amount of time that should be spent on SSR, Wu and Samuels (2004) conducted a study that found amount of time spent on reading to be positively correlated with reading achievement, aligning with the “Matthew Effect” theory of reading suggested by Cunningham and Stanovich (1998). Wu and Samuels also found that time spent on reading should take student age and reading ability into consideration to make sure students are only reading for a length they can independently focus on reading for. For older students, SSR time may last as long as 45 minutes (Anderson, 2002; Davis, 1988; Wu & Samuels, 2004), while for younger students, the program may only last 10 to 15 minutes per day. Teachers interviewed by Wiesendanger et al (2009) suggest that when working with students engaged in longer amounts of reading time, students are more likely to show gains in reading attitude if the time is divided into shorter daily sessions rather than fewer longer ones. IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 16 Consistency in what time the reading occurs in the day does not show to have much affect on the effectiveness of the program, however, younger students may benefit from expecting a regular routine (Collins, 1980; Kaisen, 1987; Wiesendanger et al., 2009). A common element in successful programs was the inclusion of a signal for the beginning and end of each session to help students get used to the routine as well as prevent any clock watching. The use of a signal was effective in SSR programs across all grade levels (Anderson, 2002; Chua, 2008; Cline & Kretke, 1980; Manning & Manning, 1984; McCracken, 1971; Pegg & Bartelheim, 2011; Siah & Kwak, 2010). Environment Providing a comfortable and quiet environment is important across all age levels. Students need to be able to focus on reading without being interrupted by the many distractions that occur throughout the day. The value of having a quiet time of the day should not be underestimated. When surveying thousands of students engaged in SSR, McCracken (1971) found that students enjoyed SSR because it was the only quiet time they had in their day. Similarly, Ivey and Broaddus (2001) collected student responses and found that students liked this time because; as one student shared “I like it because it’s quiet and because you get to just think and you don’t have to answer questions” (p. 360). In order to create this quiet and focused environment, many of the programs required that students read silently, remain in one spot for the entire time, do not talk to other students, and do not get up to use the restroom, get a drink, or a new book (Anderson, 2000; Kornelly & Smith, 2001; McCracken, 1971; Pegg & Bartelheim, 2011). To make sure students do not get up during the SSR time, it is important to allow them time to take care of personal matters before SSR time begins, as well as to instruct them to take more than one book to their place if they will finish what they are reading during the allotted IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 17 time. Establishing these rules may take some time, however, the environment will be much more conducive to focused reading once they are in place. In terms of the physical environment, it is recommended that students be in a comfortable setting. Morrow (1985) suggests that in order to increase voluntary reading in the elementary and middle school classrooms, there must be an attractive area with comfortable seating surrounded by accessible books. When possible, teachers should arrange these comfortable environments that allow students to move to a new position or location for SSR time (Wiesendanger et al., 2009), however in older grades these kinds of spaces are not always available. While having the comfort of a pillow or couch is relaxing, it is not necessary for effective implementation of SSR. Many programs have been successful in middle and high school classrooms with students sitting at their desks as long as the students are not distracted or overcrowded by those sitting around them (Davis, 1988; Chua, 2008; Cline & Kretke, 1980; Gardiner, 2005; Holt & O’Tule (1989); Kornelly & Smith, 1993). Access to Books The display of and access to great reading materials will also enhance the reading environment (Pilgreen, 2000). In the studies I reviewed however, only programs implemented in grades Kindergarten through 3rd grade had classroom libraries or discussed student access to books (Anderson, 2002; Kaisen, 1987; McCracken, 1971; Pilgreen, 2002; Reutzel et al., 2008), while the older grades expected students to bring books from home or the school library. In addition to the option of bringing books from home, students should be in book rich classrooms to increase facilitation of finding interesting books (Gambrell et al., 1996). Access not only means having books available, but also means that the books are easily accessible to students and arranged in an attractive and easy to browse way (Wiesendanger et al., IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 18 2009). Additionally, successful programs included teacher book talks (Reutzel et al., 2008; Kelley & Clausen-Grace, 2006; Wiesendanger et al., 2009) and read alouds (Kaisen, 1987; Pegg & Bartelheim, 1971; Kelley & Clausen-Grace, 2006), making these books accessible to students to promote enthusiasm and interest in reading them. Of the teachers interviewed by Wiesendanger et al. (2009) 100% stressed the importance of establishing classroom libraries that include a wide variety of reading materials. A survey conducted by Ivey and Broaddus (2001), indicated that students have interest in over twenty different genres and types of print, the most popular being magazines, adventure books, mysteries, scary stories, joke books and informational books on animals. Additionally, Cunningham and Stanovich (1998) found that of printed texts; scientific abstracts, newspapers, and popular magazines are comprised of a significantly higher number of rare words than trade books, suggesting that exposure to a variety of textual sources provides students with a wider range of vocabulary. Creating a classroom library following these recommendations can be costly. To address this issue, Fisher (2004) suggests that schools hold a book drive to build a book room in which teachers can borrow books from to fill their classroom library. He also suggests teachers apply to grants that provide money for classroom improvement. Pilgreen (2000) suggests that teachers implement a program where they rotate reading materials throughout the year so that students have a larger selection to choose from. She also recommends that teachers help students take advantage of the school and local library by teaching them how to find and check out books, providing access to a much larger selection. Book Selection Across all studies book choice is an important aspect of the SSR program. Choice provides students with a great deal of motivation by allowing them to select books that interest IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 19 them (Gambrell, 1996). In a phenomenological study, Flowerday and Schraw (2000) collected data showing teachers concur that student choice increases interest, autonomy, ownership, creativity, engagement, self-regulation and strategy use when engaged in academic activities (p.641). The effective implementation of choice in a SSR program looks different depending on the age of the students. For Kindergarten through 3rd grade programs, book selection should be scaffolded. According to Vygotskian theory, children learn and develop new skills within a Zone of Proximal Development, in which they build knowledge through the interaction with a more knowledgeable partner (Beliavsky, 2006). Selecting books that are both interesting and at the appropriate reading level is a skill, and younger students need instruction in learning how to make these choices. Through minilessons, modeling, and book conferences, teachers can work with students to help them determine if a book is at their independent level as well as teach some previewing strategies to determine the interest level of the book (Pegg & Bartell, 2011; Reutzel et al., 2008; Trudel, 2007). One way to scaffold book instruction is through leveling classroom books by color, allowing students to easily recognize which books will be at their independent level of reading. Of the studies that worked with early elementary age students there were a variety of levels of scaffolding, however all of the models came down to allowing students to select their own reading materials. In the middle grades students begin to develop increased autonomy, allowing book selection becomes a little more independent (Alexander, 2006). Students may still benefit from book selection instruction if they continue to struggle with selecting independent and interesting books (Akmal, 2002; Kelley & Clausen-Grace, 2006). Rather than whole group instruction, this tends to be successful in one on one conferences. One program design chose to limit the choice IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 20 of reading materials to novels and storybooks (Siah & Kwak, 2010) while the others did not specify any particular text or genre to be read. Choosing to allow students read from a variety of genres and authentic texts including trade books, magazines, periodicals, comic books, and newspapers provides students will a wide range of choice to access a wide range of interests (Pilgreen, 2000). At the high school level, students have developed autonomy and self-regulation skills and should be expected to independently select appropriate books without instruction or scaffolding (Alexander, 2006). Most of the SSR programs designed for this age range have limited choice of materials to books only, restricting textbooks, magazines, comics, and newspapers during the SSR time (Cline & Kretke, 1980; Kornelly & Smith, 1993). As addressed in the access section, the findings of Cunningham and Stanovich (1998) on the amount of rare words in newspapers and magazines, as well as the knowledge that students have a wide range of interests, supports the recommendation that students be allowed to select from a wide range of reading materials beyond hard and soft cover books. Limiting students to books will also limit their interest and their exposure to new words. Accountability As I discuss accountability, I define it as the act of holding a student responsible for his or her action, in this case, reading. Often, in the literature and in SSR studies, the term accountability has also taken on the meaning of assessment or evaluation. Both McCracken (1971) and Pilgreen (2000) designed seminal SSR models that have influenced many SSR programs and use the term nonaccountability in this way. In McCracken’s original design of the SSR program, he insisted that students should not be held accountable for their reading, defining accountability as book reports and records, or other required forms of response that would cause IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 21 students to feel that they were being evaluated. Pilgreen states that nonaccountability allows students to read for pleasure without being held down by assessments and evaluations (p.15). The purpose of nonaccountability in both of these programs is to allow students to focus on reading for pleasure and at their own pace without the pressure of being judged or graded on their performance. Yoon (2002) found that high accountability of reading might cause struggling and reluctant readers to shut down, and never experience the pleasure of reading. In interviewing students, McCracken (1971) found that students enjoyed the SSR time because it provided them with the freedom to read without worrying about making mistakes or proving their reading ability to others. As a comparison, Schmidt (2008) looked at the Accelerated Reader program (AR), in which students read independently to prepare for taking a quiz on the book to gain points. In this study, Schmidt found that AR decreased student’s positive attitude towards reading, causing them to focus on the assessments, which tested student’s literal knowledge of the book. This form of accountability goes directly against the goal of reading for pleasure that McCracken and Pilgreen set out to establish during the SSR time. Since McCracken’s initial design, nonaccountability has remained a key word in program designs, however, what many programs mean by this term is that students are not to be evaluated based on their reading performance. For successful implementation of a reading program, it is important that teachers are able monitor student growth and progress, as well as the effectiveness of the overall program. Various forms of follow up activities have been implemented that do not focus on evaluating students, but rather provide students with an outlet for response as well as self-regulation and reflective strategies. Based on the research, programs implemented in Kindergarten through 3rd grade should not require students to keep a record of their reading amounts or complete book reports after IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 22 finishing. During these early years, students are still working on their reading skills and strategies, and will benefit more from reading for enjoyment without the pressure of completing follow up activities. In middle school, students may be held accountable for their reading during SSR time. This can be in the form of student/teacher goal setting for reading specific numbers of pages determined during conferences. These goals must be reasonable, but push the student to focus on reading each day for the entire SSR time (Akmal, 2002; Manning & Manning, 1984). Few studies include book reports in their design, however one (Akmal, 2002) suggests that students complete book reports of a flexible format. Other programs encouraged students to reflect on their reading through journal writing (Kelley & Clausen-Grace, 2006; Siah & Kwak, 2010), peer sharing, or class sharing (Kelley & Clausen-Grace, 2006; Manning & Manning, 1984). Reutzel et al. (2008) designed an independent reading program in which students were presented with a menu of response options including a variety of creative projects, such as creating a wanted poster on one of the characters. These forms of reflection and follow up activities to reading should only be implemented once students have established the SSR routine and recognized the focus on reading for enjoyment rather than for assessment. In high school students often have heavy loads of reading for class, and this time to read for pleasure should be focused on such. Students in high school should not be held accountable for reading through reports or required number of pages, however they should be encouraged to reflect on their reading through written responses in a journal or peer sharing (Chua, 2008). They may also keep a book log to keep track of the reading they have accomplished (Kornelly & Smith, 1993). IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 23 Nonaccountability is a difficult aspect of SSR for teachers, and many feel uneasy about students engaging in an activity that does not have a measurable outcome (Fisher, 2004). The suggestions listed in this section should provide some alternatives to the traditional understanding of accountability and provide teachers with some ways to measure student engagement and growth. In the next section, I will discuss additional roles of the teacher that will also allow teachers to have a better understanding of the status of the class during SSR time. Teacher Roles Throughout the various SSR programs, teachers take on many different roles. McCracken (1971) included teacher modeling as an important aspect of the program, and later went on to state that SSR would not work without teacher modeling (1978). Methe & Hintze (2003) conducted a study on the effects of teacher modeling, and found that student’s on task reading behavior positively correlated with teacher modeling. When students see teachers reading, the value of reading becomes more transparent (Loh, 2009). This modeling should be explicit through the sharing of reading experiences and personal descriptions of how reading has enriched his or her life (Gambrell, 1996). Like many factors originally intended to be a part of SSR, the concept of teacher modeling, and the role of the teacher during this time has changed. Most programs still include modeling as an important aspect; however modeling is often only one of the teacher’s roles during this time (Anderson, 2002; Akmal, 2002; Cline & Kretke, 1980; Chua, 2008; Gardiner, 2005; Kaisen, 1987; Trudel, 2007). Other roles include providing feedback to students, reading aloud prior to the SSR time, giving book talks, instructing on how to select books, monitoring the class, and conferencing with students. Inclusion of student-teacher conferences is also common in program designs (Akmal, 2000; Manning & Manning, 1984; Reutzel et al, 2008; Siah & Kwak, 2002; Trudel, 2007). These IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 24 conferences typically occur with elementary and middle school students, and last between five and ten minutes. Akmal (2000) included conferences in which the teacher focused on developing student academic and non-academic self-concept. Teachers opened the discussion to talk about the student’s emotional state, moving onto reading efforts and student progress in meeting their reading goals, discussing book selection, and finally opening up the conversation to anything else the student desired to talk about. Kelley and Clausen-Grace (2006) designed a program called R5, which also included conferencing focused on discussing student’s reading strategies and plans. Occasionally, the conferences included the teacher modeling a specific strategy or reading aloud to the students (Trudel, 2007). For the most part, conferences included in SSR programs focus on student reading strategies, monitoring student progress, aiding book selection, and offering an outlet for book reflection. In addition to modeling and conferencing, teachers can provide students with feedback and encouragement in order to improve student’s self-perception as a reader. A student’s selfefficacy is strongly influenced by feedback from parents, teachers and peers in academic settings (Paris & Cunningham, 1996). Pilgreen (2000) included encouragement as an important trait of SSR, which she describes as adult modeling, book recommendations, and positive reinforcement. Other programs that include teacher feedback base the feedback mainly on procedural aspects of the program, letting students know how the SSR time is running and what changes might need to be made to improve the reading time (Anderson, 2002; Reutzel et al, 2008; Trudel. 2007). These programs focus on younger students in early elementary grades, since the procedure of participating in an SSR program may be new and unfamiliar to students. The importance of teacher modeling remains strong through all of the teacher roles included in studies, however some programs put more emphasis on complete independent silent IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 25 reading for all, while others put more emphasis on the teacher holding an active role, purposely modeling specific strategies to students as well as discussing books and reading strategies with students. Deciding what role to take in the classroom depends on the kinds of support that the students need. Student Roles One of the most beneficial aspects of the SSR program is the autonomy that students gain through engaging in and developing a habit of independent reading. There are also benefits of engaging in social interactions around books, as well as development of self-regulation strategies. In many programs, the students only role is to pick a book and read for the entire time, however in other programs students also engage in peer book sharing, class book sharing, buddy modeling, goal setting, and book response. As discussed in the accountability section, these roles should be encouraged, and implemented in a way that does not seek to evaluate students. Manning and Manning (1984) conducted a study looking at three different SSR models. One model followed McCracken’s 1971 design, a second model included peer sharing of books (oral reading in pairs, small group or one on one discussions, and dramatizations), and a third model included individual student teacher conferences about books as well as reading plans. The results of the study showed that the students engaged in the peer interaction model made significantly higher gains in reading attitude and reading achievement than the students in the other two models, suggesting that inclusion of peer interactions is a positive factor. Additionally, this study showed that the role of students engaged in a one on one teacher conference was effective in producing significantly higher gains in reading attitude. The National Reading Panel (2000) also reviewed this study, and concluded that while the original model did not make large IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 26 gains in reading achievement, the two models that included these variations showed student gains in reading achievement (p. 3-26). The role of goal setting, in which students determine a number of pages they will attempt to read in a week, gives students ownership of their own learning (Wiesendanger et al., 2009). Through goal setting, students develop self-regulation skills, and can track their progress and challenge themselves at comfortable levels. An additional role may also include engaging in selfselected and flexible follow up activities as described in the accountability section. Summary and Implications The seven categories described above should serve as a resource for planning and implementing a successful SSR program. Some factors, including providing a quiet, uninterrupted, and comfortable environment, access to books in the classroom, freedom of book selection, teacher modeling, and an absence of evaluative activities, are necessary to include. The remaining factors are recommended to provide teachers with options based on their students’ age and needs. There is not one correct way to design and implement SSR and teachers should not feel restricted to follow one specific model, however there are many aspects that help and hinder the experience for students as well as the desired outcomes. A chart included in the appendix serves as a user friendly resource for teachers as they craft their own SSR program. Conclusion When designed and implemented with purpose and consistency, Sustained Silent Reading is an effective program to include as part of the literacy block in Kindergarten through 12th grade classrooms. The literature reviewed shows that SSR improves student attitude toward independent reading (Chua, 2008; Cline & Kretke, 1980; Holt & O’Tule, 1989; Kornelly & Smith, 1993; McCracken, 1971; Yoon, 2002), as well as increases their reading achievement in IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 27 vocabulary, comprehension and fluency (Davis, 1988; Elley, 1992; Holt & O’Tule, 1989; Kornelly & Smith, 1993). Providing students with practice to develop their reading skills as well as their habits of engaging in reading for pleasure will help to instill a life long love of learning (Garan, 2008). A lack of consistency in the models of SSR employed by teachers and researchers is a concern that has been addressed through analysis and comparison of the various models in relation to relevant research and theories of learning. Based on these findings, a flexible model of SSR has been suggested in order to increase both reading achievement and reading attitude in students. These findings consider the frequency and duration, environment, access to books, book selection, accountability, teacher roles and student roles within the program. Recognizing the developmental range of students between Kindergarten and 12th grade, recommendations look different depending on the age of participants in the program. While many stakeholders in education remain concerned about the effectiveness of SSR based on the findings of the National Reading Panel (2000), the research in this literature review clearly shows that SSR is an effective and enjoyable practice for improving reading achievement and reading attitude. Following the provided guidelines with consideration of both the age of students and desired outcome will help teachers develop a successful SSR program. IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 28 Appendix 4th-8th Grade 9th-12th Grade Frequency & Duration Kindergarten – 3rd Grade Daily SSR Start 1 minute, build gradually to 10-15 minutes Daily SSR Start 5 minutes, build gradually to 15-25 minutes Environment Comfortable, quiet and uninterrupted Students remain in one spot Create comfortable reading areas in room to allow for change of position Wide selection of reading materials provided in classroom library Attractively arranged and easily accessible Books introduced through book talks and read alouds Access to and instruction in using school and public library Free choice from wide range of reading materials Scaffold book selection in conferences Access to Books Book Selection Comfortable, quiet and uninterrupted Students remain in one spot Create comfortable reading areas in room to allow for a change of position Wide selection of reading materials provided in classroom library Attractively arranged and easily accessible Books introduced through book talks and read alouds Access to and instruction in using school and public library Free choice from wide range of reading materials Scaffold selection of interesting and appropriate level texts through mini lessons, modeling, conferencing and color coding books by level Start 5 minutes, build gradually to 45 minutes 3 days a week or 25 minutes 5 days a week Comfortable, quiet and uninterrupted Students remain in one spot Make sure students are not over crowded if sitting at tables and desks Wide selection of books in classroom Access to local and school library Encouragement to bring own reading material Independent free choice from wide range of reading materials Monitor for appropriateness of reading material IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING Accountability Teacher Roles No record keeping or book reports Focus on developing habit of reading for pleasure Goal setting for 2nd and 3rd grade Model Reading Provide encouragement and feedback on SSR performance. Student-teacher conferencing: 5-10 minutes – discuss reading strategies, metacognition, book selection, book response and reflection Student teacher goal setting Record keeping Follow up activities: Flexible and self selected book response, metacognitive reflection, journal writing, class sharing, peer sharing Model Reading Provide encouragement for independent reading Student-teacher conferencing: 5-10 minutes – discuss reading strategies, metacognition, book selection, book response and reflection o Independent o Independent Reading Reading o Peer book sharing o Peer book sharing o Budding modeling o Buddy modeling o Class book sharing o Class book sharing nd rd o Goal setting (2 /3 o Goal setting grade) o Flexible book o Optional book response response *Factors written in italic are options to consider Student Roles 29 No reports or records Encourage written or oral responses, peer or class sharing and book talks Model Reading Provide encouragement for independent reading o Independent Reading o Optional peer book sharing o Optional class book sharing o Optional book response IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 30 References Adams. (2004). Modeling the connections between word recognition and reading. In R. B. Ruddell & N.J. Unrau (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (5th ed., pp 1219-1243). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Akmal, T. T. (2002). Ecological approaches to sustained silent reading: conferencing, contracting and relating to middle school students, The clearing house, 75(3),154-157. Alexander, P.A. (2006). Psychology in learning and instruction. Columbus, OH: Pearson Merill Prentice Hall. Anderson, C. (2000). Sustained silent reading: Try it, you’ll like it! The reading teacher, 54(3). 258-259. Beliavsky, N. (2006). Revisiting Vygotsky and Gardiner: Realizing human potential, The journal of aesthetic education, 40(2), 1-11. Chua, S.P. (2008). The effects of the sustained silent reading program on cultivating students’ habits and attitudes in reading books for leisure, Clearing house 81(4), 180-184. Cline, R. K., & Kretke, G.L. (1980). An evaluation of long-term SSR in the junior high school, Journal of reading, 23(6), 503-506. Collins, C. (1980). Sustained silent reading periods: Effect on teachers’ behaviors and students’ achievement. The elementary school journal, 81(2), 108-114. Cunningham, A. E.,& Stanovich, K. E. (1998). What reading does for the mind. American Educator, 22(1-2), 8-15. Cunningham, J. W. (2001). National reading panel report. Reading research quarterly, 36(3). 326-335. IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 31 Davis, Zephaniah T. (1988). A comparison of the effectiveness of sustained silent reading and directed reading activity on students’ reading achievement, The high school journal, 71(1), 46-48. DeBenedicts, D. & Fisher, D. (2007). Sustained silent reading, making adoptions, Voices from the middle 14(3), 29-37. Edmondson, J., Shannon, P. (2002). The will of the people, The reading teacher 55(5), 452-454. Elley, W.B. (1992). How in the world do students read? IEA study of reading literacy. International association for the evaluation of educational achievement. (Research Report No. 92-9121-002-3). Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov:80/PDFS/ED360613.pdf Fisher, D. (2004). Setting the “opportunity to read” standard: Resuscitating the SSR program in an urban high school. Journal of adolescent and adult literacy, 48(2). 138-150. Flowerday, T. & Schraw, G. (2000). Teacher beliefs about instructional choice: A phenomenological study, Journal of Educational Psychology 92(4), 634-645. Gambrell, L. B. (1996) Creating classroom cultures that foster reading motivation. The reading teacher, 50(1), 14-25. Gambrell, L. B., Palmer, B. M., Codling, R. M., Mazzoni, S. (1996). Assessing motivation to read. The reading teacher, 49, 518-433. Garan, M. E, DeVoogd, G. (2008). The benefits of sustained silent reading: Scientific research and common sense coverage. Reading Teacher 62(4), 336-334. Gardiner, S. (2005). A skill for life. Educational leadership, 63(2). 67-70. Goodman, K. S. (1994). Reading, writing, and written texts: A transactional sociopsycholinguistic view: In R. B. Ruddell, M. R. Ruddell & H. Singer (Eds.), IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 32 Theoretical models and processes of reading (4th ed., pp. 1093-1130). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Holt, B. S. & O’Tule, F. S. (1989). The effect of sustained silent reading and writing on achievement and attitudes of seventh and eighth grade students reading two years below grade level. Reading improvement, 26(4), 290-297. Ivey, G. & Broaddus, K. (2001). A survey of what makes students want to read in middle school classrooms. Reading research quarterly, 36(4). 350-377. Kaisen, J. (1987). SSR/booktime: kindergarten and 1st grade sustained silent reading. The reading teacher, 40. 532-536. Kelley, M., & Clausen-Grace, N. (Oct. 2006). R5: the sustained silent reading makeover that transformed readers. The reading teacher, 60(6). 148-156. Kornelly, D. & Smith, L. (1993). Bring back the USSR. School library journal, 39(4) p. 48. Krashen, S. (2000). Forward. In J. L. Pilgreen, The SSR handbook, How to organize and manage a sustained silent reading program. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers, Inc. Krashen, S. (2001). More smoke and mirrors: A critique of the National Reading Panel report on fluency, Phi Delta Kappan, 119-123 Lee-Daniels, S. L & Murray, B. A. (2000). DEAR me: what does it take to get children reading? The reading teacher 54(2). Loh, J. K. K. (2009). Teacher modeling: Its impact on an extensive reading program. Reading in a foreign language, 21(2), 93-118. Manning, G. L., & Manning, M. (1984). What models of recreational reading make a difference? Reading world, 23(4). 375-380. McCracken, R. A. (1971). Initiating sustained silent reading, Journal of reading, 14(8), 521-583. IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 33 McCracken, R. A., & McCracken, M. J. (1978). Modeling is the key to Sustained Silent Reading. The Reading Teacher, 31, 406–408 Methe, S. A., & Hintze, J. M. (2003). Evaluating teacher modeling as a strategy to increase student reading behavior. School Psychology Review, 32(4), 617–624. Morrow, (1985). Developing young voluntary readers: The home-the child-the school. Reading research quarterly, 25(1), 1-8. Nagy, W.E., Anderson, R.C. & Herman, P.A. (1987). Learning word meanings from context during normal reading, American educational research journal, 24(2), 237-270 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2003). Literacy skill for the world of tomorrow. (Publication No. 5381). Retrieved from http://www.uis.unesco.org/Library/Documents/pisa03-en.pdf Paris, S. G., & Cunningham, A. E. (1996). Children becoming students. In D. Berliner, & R. Calfee, Handbook of Educational Psychology (pp. 117-147). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Macmillan. Paris, S. G. (2005). Reinterpreting the development of reading skills, Reading research quarterly, 40(2), 184-202. Pilgreen, J. L. (2000). The SSR handbook, How to organize and manage a sustained silent reading program. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers, Inc. Pegg, L. A. & Bartelheim, F. J. (2011). Effects of daily read-alouds on students’ sustained silent reading. Current issues in education, 14(2). 1-8. Reutzel, D.R, Johnes, C. D., Fawson, P. C., & Smith, J. A. (2008). Scaffolded silent reading that works. The reading teacher, 62(3), 294-207. IMPLEMENTING SUSTAINED SILENT READING 34 Rosenblatt, L. (1994). Continuing the conversation: A clarification, Research in the Teaching of English, 29(3), 349-354. Schmidt, R. (2008). Really reading: What does accelerated reader teach adults and children? Language arts, 85(3). 202-211. Shanahan, T. (2006). Does he really think kids shouldn’t read? Reading today, 23(6),12. Siah, P, Kwok, W. (2010). The value of reading and the effectiveness of sustained silent reading, The clearing house, 83, 168-174. Trudel, H. (2008). Making data driven decisions: Silent reading, Reading teacher, 61(4). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Reports of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read, report of the subgroups. (NIH Publication No. 00-4754) Retrieved from http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/nrp/upload/ch3.pdf Wiesendanger, K., Braun, G. & Perry, J. (2009). Recreational reading: Useful tips for successful implementation. Reading horizons, 49(4). 269-284. Wu, Y., & Samuels, S. J. (2004). How the amount of time spent on independent reading affects reading achievement: A response to the National Reading Panel. Manuscript submitted for publication, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Minnesota. Retrieved from http://www.tc.umn.edu/~samue001/web%20pdf/time_spent_on_reading. Pdf Yoon, J. (2002). Three decades of sustained silent reading: A meta-analytic review of the effects of SSR on attitude toward reading. Reading improvement, 39(4).186-195.