capstone with abstract

advertisement

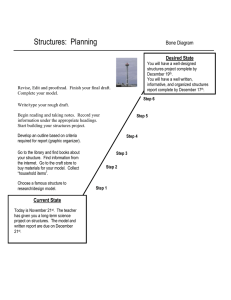

Curriculum and Instructional Leadership in the 21st CenturyA Look at Schools in Nashville and Singapore Capstone Paper submitted by: Bernard Chew in fulfillment of the requirements for M.Ed. Degree Preface and acknowledgements In this capstone paper, I shall attempt to synthesize and apply my diverse learning while pursuing my M.Ed. Degree at Vanderbilt University. I came to Vanderbilt on a Ministry of Education (Singapore) scholarship. As a Singaporean educator likely to return to Vice-Principalship in a Singapore school, I had hoped that my year at Vanderbilt would equip me with the necessary knowledge and skills to be an effective curriculum and instructional leader when I return to Singapore. Coming to the end of my time at Vanderbilt (I have two summer courses remaining), I have to say that the learning experiences I have had have given me much food for thought. The different courses I have taken (particular those directly related to curriculum and school leadership), as well as the practicum experience in five different schools in the Greater Nashville area, have provided me with a clearer vision of what good curriculum and instructional leadership would look like. Thus, I was interested not only in the theoretical aspects of teaching and learning, and instructional leadership, I also wanted to have a good idea of how the theories are put into practice. I am thankful that my practicum experience as well as opportunities in other courses to interview school leaders in the Greater Nashville area has afforded me the opportunity to see the theories in action. I also had an opportunity to teach in a high school class as part of my Social Studies methods class. The capstone paper is, therefore, a distillation of my learning and will also serve to help me organize my thoughts into a coherent whole as I prepare to return to school. In the course of my learning, I am indebted to many people- to all my lecturers at VanderbiltProf. Pearl Sims, Prof. Sarah Buchanan, Prof. Naomi Tyler, Prof. Mary Bradshaw, Prof. Lynn Heady, Prof. Thomas Smith, Prof. Steven Baum, Prof. Mark Cannon and Prof. Leigh Wadsworth, I am grateful for the generous sharing of your knowledge and experience. You have set high standards for our learning and given us great support and encouragement along the way. I am also thankful to the school leaders at Big Picture High School (Mr. Ralph Tagg), Tom Joy Elementary (Ms. Elana Jones), Hillsboro High School (Mrs. Larue-Lucas), Montgomery Bell Academy (Mr. Alan Coverstone) and Ravenwood High School (Dr. Pam Vaden and Ms. Lily Leffler) for generously sharing their time to facilitate my practicum. There are others who have also shared their time in facilitating my learning in the different courses, such as Ms. Karen Hawkins from the Williamson County District Office,Mr. Christian Sawyer from Hillsboro High, Ms. Kelly Pitsenburger and Ms. Ellinor Axford at Kenrose Elementary, and the staff at Saddle Up!. Finally, I am also grateful to Prof. Rich Milner and Prof. Cliff Hofwolt for their guidance and advice. And of course, to my wife Hsiao Yun and children, Evan and Chloe, who have made my time in Nashville doubly enjoyable because they are here to share to adventure with me. Abstract Singapore and U.S. schools face similar challenges in preparing students for life in the 21st Century workplace, home and community. As globalization proceeds apace, future graduates are expected to possess 21st Century attitudes, skills and knowledge. Schools can help prepare students for the 21st Century world by adopting responsive and relevant curricula, practicing effective and engaging pedagogy, and having authentic assessment that drives learning. However, schools and teachers face many challenges in delivering 21st Century education. Schools remain accountable for performance in standardized tests and nationalized examinations, and teachers are struggle to find time to reflect on and improve their instructional and assessment practices. School leaders, curriculum developers and teachers need a common language too to ensure sound educational principles guide curriculum design, implementation and assessment. Adopting a good teaching and learning framework, such as the How People Learn framework or Singapore’s PETALs framework can help in this regard. For educational reform movements designed to deliver 21st Century education (such as Singapore’s Teach Less, Learn More movement or U.S.’s standards-based reforms) to succeed, strong support from district or national authorities and strategic implementation by school leaders are necessary. District or national authorities should provide schools with adequate resources and teacher training, and facilitate the capturing and sharing of best practices among schools. School leaders need to generate buy-in among teachers, garner and deploy resources (from external stakeholders if necessary), train and empower teachers and create professional learning communities to sustain reforms. As a practicing school leader, I have designed a personal curricular and instructional leadership plan which includes a two-year training program to equip teachers to design an aligned curricular, instructional and assessment program (using the Understanding by Design framework) resulting in teaching for deep understanding, a teacher assessment plan aligned with the curricular, instructional and assessment objectives, and a plan to establish professional learning communities to promote and sustain collegial teacher reflection and professional improvement. With the professional engagement and conscientious application of district or national administrators, school leaders and teachers, I believe a relevant, effective curriculum can be delivered to prepare our students for the 21st Century. Introduction Many scholars within and outside of the education field agree that curriculum and instruction in schools in contemporary societies like the U.S. and Singapore need to be responsive to the trends of the 21st Century. The attitudes, skills and knowledge that these students will need for a successful and fulfilling life at the workplace, at home and in the community are more complex than ever, and, I would argue, should be developed while they are still in school. However, as Linda Darling-Hammond (2000) so perceptively pointed out in her discussion on the futures of teaching in American education, the public education systems around the world are scrambling to keep pace with the changes required to provide these students with a relevant education for the 21st Century. How leaders of schools in these systems respond to the challenges posed by the changing trends will, to a large extent, determine the futures of students today, and have an indirect impact on the economic and social vitality of these societies. In this paper, I will examine the challenges 21st Century schools face in adequately preparing their students for life after graduation, looking at views from within and outside education. I will then examine three different frameworks that school leaders and curriculum developers can consider adopting to facilitate their curricular and instructional leadership. I will then explore how school leaders in Nashville and Singapore have exercised their curricular and instructional leadership, . Finally, I will briefly describe a personal curricular and instructional plan that I could implement when I return to a school in Singapore. Challenges Facing 21st Century Schools- Views from Within and Outside Education Darling-Hammond (2000) argued that while demands placed on today’s graduates from school have vastly increased, many schools in the U.S. are still run on a factory-model system designed to prepare students in the pre-Information Age, when the objective was for the masses to acquire basic skills in preparation for routine work in assembly lines. U.S. teachers, as I have discovered, teach about 5 hours a day, leaving little time for lesson preparation, professional development and dialogue with colleagues. This meant that despite recent efforts to reform curricula in U.S. schools through the adoption of rigorous standards, teachers are hard-pressed to design meaningful learning experiences and differentiate instruction for diverse learners (Darling-Hammond, 2000). Given this lack of time, teachers often resort to focusing on what they believe to be the most salient priorities in the classroomsthe need to boost standardized test scores and “get through” the syllabus. This would sometimes result in “mentioning”- superficial treatment of important concepts and skills- rather than allowing for indepth exploration and discussion (Alexander, 2006). Even when teachers were motivated to provide the engaging and relevant learning experiences for students, they were often short of ideas and had little time to observe their colleagues and learn new approaches, leading to little change in curricula and instructional methods. Similarly, Tony Wagner (2008), in an article in the October 2008 issue of Educational Leadership, suggests that educators’ view of rigor needed to be redefined. He argued that students today need seven critical survival skills to thrive in the 21st Century: (a) Critical thinking and problem solving (b) Collaboration and leadership (c) Agility and adaptability (d) Initiative and entrepreneurialism (e) Effective oral and written communication (f) Accessing and analyzing information (g) Curiosity and Imagination Wagner’s list of survival skills were derived from extensive conversations he had with business, nonprofit, philanthropic and education leaders. What these leaders felt were necessary skills for schools to develop in students however, was largely absent in the classrooms that Wagner visited. Teachers were instead only delivering, in his words, “one curriculum: test prep”. While schools seemed relatively stagnant, or to use Eisner’s (1990) more positive term-stable, demands on students have increased exponentially. The proliferation of information-communication technology (ICT) and the subsequent globalization of the workplace and society have required that schools prepare students differently from the past. Don Tapscott (2009), Daniel Pink (2006) and Thomas Friedman (2007) have all written about the sweeping changes in the workplace and community brought about by globalization and technological advances, with important ramifications for education. Friedman (2007) and Pink (2006) cited several trends which would impact students in the U.S. and Singapore as they prepare for life in the 21st Century workplace. Firstly, the low cost of Internet connectivity and other related technologies like Voice-Over Internet Protocol (VoIP) has resulted in the emigration of jobs which used to be done in developed economies like those in the U.S. and Singapore. Many of the routine administrative functions of companies like preparation of official documents or even call center functions have been outsourced to English-speaking developing countries like India and the Philippines. Apart from outsourcing, Pink (2006) also pointed out that automation of many previously manual work processes has also placed greater demands on the workers of today. The Partnership for 21st Century Skills, a public-private organization of leaders and educators in business and education, have succinctly identified in their 2004 report key skillsets and knowledge that students would need in the 21st Century. Three important skills are seen as critical for students to develop (for a more detailed explanation of these skills, please refer to Appendix 1):(a) information and communication skills (b) thinking and problem-solving skills (c)interpersonal and self-directional skills Not only is the development of these skills important, the Report also emphasized the importance of developing these skills using 21st Century information-communication technology (ICT) tools such as spreadsheets, design software, word processors, emails, Internet search engines and elearning platforms. Given the ubiquity of these ICT tools in the workplace, students should be well- exposed to them during their time in school. This is especially important for students who may not have access to computers and the Internet at home. Such students will be at a distinct disadvantage if they did not have a chance to work with these tools and develop a basic ICT literacy. In fact, Tapscott (2007) went further to suggest that the use of ICT tools in the classroom not only prepares students for a brighter future, they are necessary because our students' lives are so enmeshed with technology that the more traditional chalk-and-talk pedegogy has become extremely disengaging for them. Teachers, Tapscott argued, need to cut back on lecturing and teaching to the test, and instead use technology to allow students to learn collaboratively and cultivate lifelong learning skills. Finally, the 21st Century Skills report also highlighted the need to focus on the teaching and learning of 21st century content. The report focused on three general areas of 21st Century Contentglobal awareness, financial, economic and business literacy, and civic literacy. With globalization leading to similar challenges in developed societies around the world, it is no surprise that these three areas applied equally well to Singapore and the U.S. Certainly, with many jobs nowadays requiring extensive regional travel, global awareness should be an important component of any curriculum. Similarly, financial, economic and business literacy is key to developing a generation of school leavers who will be in touch with the challenges and opportunities present in today's global workplace. While these first two areas allow our students to contribute comfortably in the workplace, civic literacy is also important because that will allow societies to stay cohesive even as our graduates increasingly find themselves working outside of Singapore (or the U.S.). Aside from developing 21st Century skills using 21st Century tools and emphasizing 21st Century content, it is also worthwhile for schools and curriculum developers to consider some of the other competencies that will stand our students in good stead when they graduate from school. Pink (2006) argued that the shift from the Information Age to an emerging Conceptual Age will require students to develop their right-brain capabilities rather than the left-brain ones which dominated the Information Age. Pink argued that the material abundance, competition from the emerging Asian giants of China and India, and automation of many jobs meant that it was no longer sufficient for American graduates to possess the traditional comparative advantages of left-brain capabilities. Instead, Pink suggested that those with well-developed right-brain abilities, or the “six senses” (Design, Story, Symphony, Empathy, Play and Meaning) as he called them, will be the ones to set the tempo of life in the Conceptual Age. If Pink is to be believed (and he does make a compelling case), then our traditional emphasis on developing logical abilities in the classroom will not prepare our students adequately for life. Built into our curricula would have to be opportunities for students to develop important social-emotional capacities and creative abilities. With the demands of the workplace, home and community becoming increasingly complex, it is incumbent upon curriculum developers, school leaders and teachers to be highly reflective about the curricula and instruction that is being delivered to 21st Century students. Schools and personnel at the district level (or in Singapore's case, in the Ministry of Education) need to have a teaching and learning framework that will ensure that there is a relevant curriculum, and effective instruction and assessment. In the next section, I will briefly examine three frameworks I believe are useful in helping curriculum developers, school leaders and teachers develop and implement effective curricula for students. Possible frameworks for curriculum and instructional leadership How People Learn framework- Bransford, et.al. (2000) Bransford, et.al. (2000) provided an example of a framework which is responsive to the needs of 21st Century learners. The How People Learn (HPL) framework emphasizes the importance of 4 perspectives on learning environments- learner-centeredness, knowledge-centeredness, assessmentcenteredness and community centeredness. Briefly, the framework suggests that a good learning environment should:(a) takes into consideration the knowledge, skills, attitudes and beliefs that students bring to the learning setting; (b) focus on helping students learn in a way that leads to understanding and subsequent transfer of knowledge; (c)include assessment that is consistent with learning goals and which provides students with useful feedback; and (d) leverages on community (both within and outside the classroom) to facilitate learning. The HPL framework is a broad framework that lays out very well the important broad principles for effective teaching and learning. For curriculum developers and curriculum leaders in schools, its usefulness lies in the fact that it encompasses all the critical perspectives from which to understand good teaching and learning, and is well-informed by research about how people learn. Curriculum developers and school leaders would do well to take all four perspectives offered by this framework into consideration when designing and implementing curricula. Teachers, too, would benefit greatly from understanding these principles when delivering the curricula in the classrooms. However, for curriculum developers and school leaders, to put the framework into practice would require a fair amount of thought going into how these broad principles can translated into actual practice. In this sense, a framework that offers a systematic way of translating research-based principles into a practicable curriculum would be very helpful. Understanding by Design (UbD) which I will discuss later in the paper, is one such framework. PETALS framework- Ministry of Education, Singapore. As part of the larger Teach Less, Learn More (TLLM) Movement (see Appendix 2 for a brief description of TLLM), the PETALSTM Framework was conceived by the Ministry as a tool to help school leaders and teachers to understand the dynamics between what a teacher does and what a student experiences. It also provides all educators in Singapore with a common professional language and vocabulary to use in conversations about curriculum and instruction (Ministry of Education website: http://www3.moe.edu.sg/press/2008/pr20080108.htm). It is similar to the perspectives framework in that it is founded upon sound education theories and research. In conceiving the framework, teachers' experiences and students' feedback were also solicited and incorporated. PETALS is an acronym which stands for 5 important dimensions of teaching and learning which teachers should consider when designing their instruction in order to maximize student engagement: a. PEDAGOGY that considers students' readiness to learn and learning styles; b. EXPERIENCES OF LEARNING that stretch students' thinking and independent learning, and promotes inter-connectedness across topics and subject areas; c. TONE OF ENVIRONMENT which is safe and stimulating; d. ASSESSMENT practices that are aligned to learning goals and provide information and feedback to students to improve learning; and e. LEARNING CONTENT which is relevant and authentic. To help see how these 5 dimensions might fit together, I have visually re-arranged them: EXPERIENCE OF LEARNING: Students’ Experience Curricular and Instructional Practices The Foundation Students are effectively engaged and prepared for life in the 21st Century LEARNING CONTENT: A relevant and rigorous curriculum for the 21st Century PEDAGOGY: ASSESSMENT: Relevant, studentfocused pedagogy to engage 21st Century learners Rigorous assessment requiring students to demonstrate transfer of learning TONE OF ENVIRONMENT: Positive teacher-student relationships to create a positive learning Figure 1: Teaching and Learning Framework environment Figure 1- PETALS Framework Rearranged By rearranging the five dimensions of the framework, I have put the tone of environment as the foundation of the framework. This is because I believe that the best curriculum, instructional practice and assessments will not be effectively if a positive tone of environment is not established in a school or classroom. I have put the three dimensions of Learning content, Pedagogy and Assessment in the middle of the framework. For teachers, curriculum developers and school leaders, the decisions they have to make regarding what to teach, how to teach and how to assess learning will be encapsulated in these dimensions. Importantly, there has to be alignment and consistency throughout these three dimensions. When the above 4 dimensions are effectively implemented in a school, then students' Experience of learning will naturally be engaging and effective in preparing them for life in the 21st Century. There are many similarities between the PETALs and HPL frameworks. Both are based on sound educational research, and both take a holistic view of the different elements which make for engaging and effective learning experiences. There may be subtle differences which arise from the different contexts in which the frameworks were conceived, such as the emphasis on connections to the borader community in the HPL model as opposed to the narrower dimension of the tone of environment in PETALs. As broad guiding frameworks for curricular and instructional leaders, however, both frameworks are theoretically sound and logical. Understanding by Design- Wiggins and McTighe (2005) Key to both the HPL and PETALS frameworks is the emphasis on helping students to develop understanding and thinking skills rather than simply learning by rote. The Understanding by Design (UbD) framework takes this emphasis on understanding further by making understanding the central aim of all teaching and learning. UbD offers curriculum developers, school leaders and teacher a method to align curriculum, assessment and instruction. This is through a process of backward design, where curriculum and instructional designers begin with the end in mind- in this case, by considering the learning goals. A template such as the one in Figure 2 is used to guide them in the conceiving the curriculum, assessment and instruction for a particular unit of lessons. Stage 1- Desired Results (Relevance Unit) Established Goals: • What relevant goals (e.g., content standards, course or program objectives, learning outcomes) will this design address? Understandings: Essential Questions: Students will understand that: • What provocative questions will foster inquiry, understanding, and transfer of learning? • What are the big ideas? • What specific understandings about them are desired? • What misunderstandings are predictable? Students will know: Students will be able to: • What key knowledge and skills will students acquire as a result of this unit? • What should they eventually be able to do as a result of such knowledge and skills? Stage 2: Assessment Evidence Performance Tasks: Other Evidence: • Through what authentic performance tasks will students demonstrate the desired understandings? • By what criteria will performances of understanding be judged? • Through what other evidence (e.g., quizzes, tests, academic prompts, observations, homework, journals) will students demonstrate achievement of the desired results? • How will students reflect upon and self-assess their learning? Stage 3: Learning Plan Learning Activities: What learning experiences and instruction will enable students to achieve the desired results? How will the design W = Help the students know Where the unit is going and What is expected? Help the teacher know Where the students are coming from (prior knowledge, interests)? H = Hook all students and Hold their interest? E = Equip students, help them Experience the key ideas and Explore the issues? R = Provide opportunities to Rethink and Revise their understandings and work? E = Allow students to Evaluate their work and its implications? T = Be Tailored (personalized) to the different needs, interests, and abilities of learners? O = Be Organized to maximize initial and sustained engagement as well as effective learning? • What relevant goals (e.g., content standards, course or program objectives, learning outcomes) will this design address? Figure 2:- 1-Page UbD Template [Source: Wiggins and McTighe (2005)] In this framework, learning objectives are listed as Big Ideas (or established goals), Understandings and Essential Questions. The emphasis on Big Ideas serve to point curriculum developers and teachers to the umbrella concepts that under-gird much knowledge in the different disciplines. Big Ideas form the “core” of the subject and are generally abstract and counterintuitive (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005). By focusing on these Big Ideas as the core of the teaching and learning experience, curriculum developers can ensure that students are able to make connections across topics and subjects, and uncover the structures of each subject. This follows Bruner's (1960) thinking: Grasping the structure of a subject is understanding it in a way that permits many other things to be related to it meaningfully. To learn structure, in short is to learn how things are related. The making of such connections also lead to expert knowledge. Bransford, et. al. (2000) suggest that one evidence of student understanding is the ability to notice features and meaningful patterns of information, much as an expert in a subject matter does. The emphasis on making connections, I would argue, plays a critical role in preparing students to develop the thinking and problem-solving skills needed in the 21st Century. The Big Ideas are then translated into Understandings and Essential Questions. To help curriculum developers and teachers understand Understanding, Wiggins and McTighe define six facets of understanding which can give them clear evidence that students have developed deep understanding of their subject matter. These six facets are Explanation, Interpretation, Application, Perspective, Empathy and Self-Knowledge. Interestingly, these facets reflect the importance of developing the whole brain which Pink (2006) emphasized. Explanation, Interpretation and Application are higherorder left-brain skills, while Perspective, Empathy and Self-Knowledge are right-brain abilities, with Perspective and Empathy closely mirroring 2 of Pink's six senses (Symphony and Empathy). Once curriculum developers and teachers have distilled the Big ideas into Understandings, they then consider the Essential Questions that will then guide the design of assessment and learning activities. In UbD, once the learning goals have been identified and distilled into Big Ideas, Understandings and Essential Questions, the curriculum developers and teachers then consider the assessment evidence that will help inform if students have gained the desired understanding, before they consider the learning activities. This is in the form of performance tasks that require students to demonstrate transfer of learning and other evidence of student learning. Here, it is worthwhile noting that the emphasis on performance tasks as a critical mode of assessment de-emphasizes the standardized tests and examinations which are most commonly associated with assessment. In Singapore, this is consistent with the Ministry's call under TLLM to teach more for “the test of life”, and less for “a life of tests”. However, in reality, the high-stakes national examinations at the sixth, tenth and twelfth grades often discourage teachers from adopting assessment modes (such as project work) which are more aligned to the goals of preparing the 21st Century learner for life. Similarly, in the schools I have been to in Nashville, No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and high-stakes testing have moved teachers away from authentic performance tasks to teaching for the tests and examinations. Only after the appropriate assessment evidence has been decided do curriculum developers and teachers then consider the learning activities that can be carried out to help students fulfill the performance tasks. By getting curriculum developers and teachers to consider assessment before instruction (when it is probably more intuitive for teachers to do the reverse), UbD helps ensure that there is alignment between curriculum, assessment and instruction. In this sense, it is a useful, practicable model that translates the excellent theory-based intent of both the HPL and the PETALS frameworks into actual practice in the classroom. Thus, I feel that UbD is an ideal model for school leaders to consider in driving the curriculum and instruction in a 21st Century school. I will now turn my attention to considering how a school leader in a 21st Century school can use the ideas above in his/her curricular and instructional leadership in a school, bearing in mind many of the practical challenges that will inevitably arise. What I will discuss in the next two sections has largely been informed by my experiences in Singapore schools, as well as what I have learned from experiences in schools in the Greater Nashville area. Challenges to effective curricular and instructional leadership in a 21st Century school Much has been written about the challenges facing school leaders in translating the good intentions of various school reforms into actual improvements in the learning experiences of students. Despite much research pointing to the necessity of reforming instruction in U.S. Schools, most instructional leaders have found it extremely challenging to implement changes in the way teaching and learning takes place. Elmore (1996) stated it best: Innovations that require large changes in the core of educational practice seldom penetrate more than a small fraction of U.S. Schools and classrooms, and seldom last very long when they do. To Elmore, part of the problem lies in the absence of incentives. Certainly, this might well be the case in the U.S. Context, where teachers' pay is largely tied to the numbers of years in teaching and to academic qualifications, rather than actual performance in the classrooms. Dr. Pam Vaden, principal of Ravenwood High, felt that one of the main challenges to good teaching and learning in her school was the “motivation of teachers after they had been awarded tenure.” In Singapore, on the other hand, there is a yearly performance bonus paid to teachers. Teachers can be paid up to four extra months of pay in March if they have done outstanding work the year before. However, it should be noted that performance of Singapore teachers is measured by several factors, and does not place much emphasis on the quality of teaching and learning in the classroom. The teacher assessment instrument does not provide much guidance to teachers on what effective teaching looks like either. Thus, while teachers may be motivated to do well, existing documents do not help teachers to effectively reflect on their own professional practice. Aside from teachers' motivation, another challenge to effective instructional leadership is the difficulty in creating a culture of continuous learning and improvement in a school. Coburn (2003) suggested that school leaders consider four factors when thinking about how to implement reforms within their own schools: (a) depth of change in instructional practice, which may require teachers to undertake a fundamental reconsideration of their core beliefs about teaching; (b) sustainability of reform, which requires schools to ensure that the level of resources allocated allows the reform to continue for an extended period of time; (c)spread of reform, evidenced by an increasing number of teachers and classrooms being impacted by the reforms; and (d) shift in ownership of the reforms to the teachers. Applying Coburn's principles to instructional leadership in a school would (ideally) require instructional leaders to establish professional learning communities among teachers. Teachers need to be given the time, resources and opportunity to carry out professional dialogues with colleagues with a view to reflecting on, and improving their own instructional practice. Apart from improving individual teachers' pedagogical and assessment practices, such learning communities can also be the platform for curricular reform when teachers collaboratively re-design the learning experiences of students. In the next section, I will review some of the professional learning communities that have been or are being established in schools in Singapore and Nashville. A third challenge is creating the room for curricular and instructional reform. If students are to be given the opportunity to examine the concepts they learn in depth, then the curriculum's breadth may need to be re-examined. One oft-quoted lament of teachers looking to get students to engage deeply with the information presented in their subject areas is the need to “cover the content”, especially when the content is deemed necessary for standardized testing purposes. In this sense, I am glad that the Ministry of Education in Singapore is constantly looking to reduce the breadth of the curriculum in order to create the room for teachers to engage students more deeply. Finally, in both the U.S. and Singapore, the continued emphasis placed on standardized highstakes tests and examinations is a major distraction for curriculum developers and teachers considering how best they can prepare their students for life in the 21st Century. Unless these tests and examinations can be improved so that they assess students' abilities to think critically and make connections, performance on these tests and examinations are unlikely to indicate the students' readiness for work and life in the 21st Century. Even if such improvements are made, tests and examinations are still limited in that they do not assess many of the skills and attitudes critical to students' real-life success in this day and age. Students' interpersonal ability, verbal communication skills and many of the right-brain aptitudes described earlier cannot be assessed through tests and examinations. I believe that many educators know this. Yet the challenge remains: how can educators help important stakeholders such as parents and policy makers (who are looking for a way to keep schools accountable for the utilization of public resources) understand this imperative? These challenges notwithstanding, I have seen teachers and administrators in Singapore and Nashville doing much to ensure that Singaporean and Nashvillian students are prepared to face the challenges of this century. I will now turn to discussing some of the efforts that schools and administrators in Singapore and Nashville have made to effect 21st Century curricula and instruction. Theory into practice in Singapore and Nashville schools From the administrators' viewpoint- TLLM in Singapore The TLLM Movement in Singapore offers a good example of how administrators beyond the school level can help school leaders by creating the right conditions for schools to implement curricular and instructional reforms to cater to the changing educational needs of 21st Century learners. Mindful of the challenges facing schools and teachers, Ministry of Education (MOE) policy-makers were determined to help schools create the necessary conditions to implement curricular and instructional reforms. As I had the privilege to be a Secretariat member of the national TLLM Facilitation Committee (TLLM FC), I had the opportunity to understand how MOE went about facilitating the work of schools in this regard. Firstly, the TLLM FC envisioned that schools and teachers should own the reforms, working from the principle of Top-Down Support for Ground-Up Initiatives. This was borne out of the belief that schools should customize their curricula and instruction to the needs of the unique profiles of students. To encourage ground-up ownership, the TLLM FC invited interested schools to propose curricular and instructional reforms within their schools under the TLLM Ignite! scheme for SchoolBased Curriculum Innovation (SBCI). The proposals were assessed by MOE administrators according to the following criteria:(a) whether the reform was founded upon sound educational theory; (b) whether the reform was innovative, i.e. The curriculum/ instructional strategies proposed had not previously been used in any school for the targeted profile of students. (That is not to say that the curriculum/ instructional strategies had to be entirely novel in Singapore. In fact, many of the successful applicant schools adopted strategies which had first been used in Gifted Education programs in other schools and adapted them for the different profile of students in their schools.) (c)whether the school as a whole was ready for the reforms. There should be some indication that school leaders and teachers in the school were prepared for the additional work required to implement the changes, and that there was a culture of learning already present in the school. From the various proposals, senior MOE administrators in the TLLM FC selected 29 schools in the first instance to be TLLM Ignite! schools. These schools were provided with additional resources to help them implement their ideas. These included additional staffing, financial resources for smallscale infrastructural development, and additional training and consultancy for teachers. In addition, the schools would appoint a Research Advocate, who would be trained to carry out action research to study the impact of these initiatives. These Research Advocates' teaching loads in school were halved to allow the time to attend training and carry out the research. Schools selected would also be required to publish the findings from their action research so that other schools could also learn from their experiences. As well, these schools were asked to share their experiences regularly with other schools to encourage the proliferation of good curricular and instructional practices. The success of the TLLM Ignite! approach to encouraging school-based reform was evident in that while 29 proposals were deemed worthy of additional support in the first phase of evaluations in early 2006, the second phase of evaluations in 2007 threw up 106 worthy proposals from 100 schools. In addition to TLLM Ignite!, other policies were implemented by MOE to facilitate curricular and instructional reforms. For example, staffing levels for all schools were gradually increased, with the teaching force increasing from 27000 to 30000 in the last decade. Other paraprofessional positions were also added- more school counselors, Special Needs Officers, Allied Educators (in effect, teacher assistants) and school administrators. The additional manpower allowed schools to reduce the teaching workload of teachers by 1 hour each weekly. Schools were asked to use this hour gained to organize teachers into professional learning communities. Schools thus structured into their scheduling considerations “Timetabled Reflection Time”, where teachers would gather in small teams to reflect on and improve curricula and instructional practices. From school leaders' viewpoint- lessons from Nashville schools Despite the extensive support given by MOE to schools in Singapore, many of the curricular and instructional practices in Singapore classrooms are still teacher-centered and, in my opinion, not preparing our students for life in the 21st Century well. Therefore, it was a valuable learning experience for me to observe many good curricular and instructional practices during my practicum stint in Nashville schools. As part of my practicum, I spent 3 days each at five schools in Davidson and Williamson counties, each with very different student populations and therefore different needs. In this section, I will highlight some of the best curricular and instructional leadership practices that I observed in these five schools which I believe can be incorporated into my own leadership practices. Emphasis on transfer of learning Compared to schools in Singapore, I observed a much greater emphasis placed on transfer of learning. Performance-based assessment that required students to demonstrate transfer of knowledge were often used in the five schools I was at. For example, Ravenwood Runway was a project at Ravenwood High that required different Career and Technical Education classes to apply the skills they learned in their various classes collaboratively to put up a modeling show. Students use the fashion design, marketing, stage management and graphic design skills to design the clothes, market the event, manage the lights and sounds on stage and design the publicity posters and websites. At Big Picture High School, authentic learning is achieved through a consistent program of internships for it students throughout the four years in high school. Teachers are encouraged to help their students connect what they learned in the classrooms to their internship experiences. In Hillsboro High School’s career academies and Ravenwood High’s Career and Technical Education classes, students pick up skills which are valuable in today’s workplace. Students take up electives in applied areas of study such as digital design, multimedia production, cosmetology, architecture and virtual enterprise, getting an early immersion into possible college majors and career choices. This not only keeps students engaged as they are given an opportunity to pursue their interests, but also help students see how their learning in the traditional subject areas (English, Math, Science, Social Studies) were useful in their future workplaces as well. Singapore has begun to offer students electives, but these electives are not full courses but rather non-examinable modules offered for a few days a year. Professional learning communities At Ravenwood High, teachers are organized into subject-area teams which meet every Monday morning to discuss how the curriculum, assessment and pedagogy in their classrooms can be improved for an hour weekly. These sessions are facilitated by the department chairs and are made possible by having students arrive in school an hour late on Mondays. From the feedback I got from the teachers, they really appreciated the opportunity to work collaboratively in teams and had learned much from one another through these communities. While it imposed some inconvenience on students (having to report to school later on Mondays), Power Mondays have clearly had an impact on the curriculum and instruction at Ravenwood. Teachers I spoke to pointed out that many of their innovative curricular ideas, such as geocaching lessons and Project Ravenwood Runway were borne out of discussions on Power Mondays. At Montgomery Bell Academy (MBA), professional learning communities are structured differently. The Academic Dean, Mr. Alan Coverstone facilitates Center for Excellence in Teaching (CET) sessions, where teachers discuss the latest trends and issues related to curriculum and instruction while having their lunches. At the CET session I observed, teachers were actively participating in the discussions on the learning needs of the digital generation, and reflecting on implications for their own instructional practices. Apart from encouraging teachers to take ownership of curricular and instructional reforms, professional learning communities also help instructional leaders overcome another key challenge to effective instructional leadership- the school leader's own lack of expert pedagogical content knowledge in all the different subject areas taught in the school (Stein and Nelson, 2003). Tapping on community resources When a curriculum is radically different from what has been traditionally offered, as in the case of Big Picture High, the necessary resources may not exist within the schools. In this case, community resources may be tapped. Such is the case with internships at Big Picture High, where its principal, Mr. Ralph Tagg, spends much time networking with community partners such as members of the Nashville Chamber of Commerce, which help facilitate the internships for the students. MBA, which relies heavily on the gifts of alumni and parents to maintain the quality of learning experiences for its students, actually has an entire office of 7 staff devoted to maintaining relations with its alumni. MBA also works with schools in various countries to run an international exchange program. The program helps MBA students to gain a global perspective and thus, prepares them early for life in a globalized environment. Such opportunities are available to students only because the school has established partnerships with others in the community. Personal curricular and instructional leadership plan I am looking forward to applying what I have learned during my time at Vanderbilt when I return to a school in Singapore. I envision that to exercise effective curricular and instructional leadership, I will have to carry out three specific leadership roles: (a) professional development of teachers to help them appreciate the importance of remembering why they teach, reflecting on what they teach, and reconsidering how they teach; (b) assessment of teachers' competencies in preparing students for the 21st Century; and (c)establishment of professional learning communities to allow teachers to individually and collectively reflect on what they teach, and how they teach and assess learning. Professional development of teachers and assessment of teachers' competencies As part of an assignment for one of my courses, I designed a two-year training program for teachers to help them effectively teach the 21st Century learner, using the UbD framework. The training plan centers around the three Big Ideas of Relationships, Relevance and Rigor. The entire training plan is at Appendix 3. This first year of training will help teachers better understand the learning needs of 21st Century learners. Important questions such as “What does a 21st Century graduate need to learn in order to succeed?”, “How is the digital generation different from older generations? How does this impact their learning?”, “How should instructional and assessment practices be changed to better meet the needs of 21st Century, digital learners?”, “How do we know that students have truly learned?”, and “What evidence would be able to tell us that students have truly understood what they learned?” will be explored in depth so that teachers can see the need to change their established practices in the classroom. Only after teachers are able to appreciate the learning needs of the 21st Century learners will they then be trained in the mechanics of UbD. UbD will then be adopted as the unit design framework in the school. The training plan also includes rubrics to assess how well teachers are able to transfer what they learned during the training sessions to their instructional practice in the classrooms. Aggregated data from teacher observations will also help me assess the effectiveness and impact of the training. Establishment of professional learning communities In order that the reforms may be sustained, professional learning communities should be formed within the school. I plan to organize teachers into subject-areas teams led by their respective Heads of Departments. These teams will meet for one hour weekly from the second year onwards to collaboratively work on re-designing their lesson units. In the long run, these teams will also use protocols such as the Atlas protocols to examine students' learning artifacts together so that they can gain deeper insights into whether students are learning effectively. These meetings can also serve as opportunities for teachers to share their own best practices so that these practices can be replicated in other classes as well. Another possibility for helping teachers learn from one another in the long run is to implement lesson study. Conclusion My time at Vanderbilt has given me a sharper focus and vision of what effective teaching and learning is. It has also given me an opportunity to reflect on the challenges that I have faced and will face as an instructional leader. The courses and my practicum have given me many ideas about how I can translate the clearer vision of effective teaching and learning into meaningful learning experiences in the classrooms. References Alexander, P. A. (2006). Psychology in Learning and Instruction: Prentice Hall: New Jersey. Bransford, J., Brown, A., & Cocking, R. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. Bransford, J., Derry, S., Berliner, D., Hammerness, K., & Beckett, K. L. (2005). Theories of learning and their roles in teaching. In L. Darling-Hammond & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 40-87). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Coburn, C. (2003). Rethinking scale: Moving beyond numbers to deep and lasting change. Educational Researcher 32, 6 (3-12). Darling-Hammond (2000). Futures of Teaching in American Education. Journal of Educational Change, 1 (4), 1389-2843. Eisner, E.W. (1990). Who Decides What Schools Teach? Phi Delta Kappan 71(3), 523-526. Elmore, R. E. (1996). Getting to scale with good educational practice. Harvard Educational Review 66 (1), 1-26. Elmore, R. (2000). "Building a New Structure for School Leadership," Shanker Institute. Fink, E. & Resnick, L.B. (2001, April). Developing principals as instructional leaders. Phi Delta Kappan, 82(8), 598-606. Friedman, T. L. (2005). The World is Flat. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Grossman, P., Wineburg, S., & Woolworth, S. (2001). Toward a theory of teacher community. Teachers College Record, 103(6), 942-1012. Pink, D.H. (2005). A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers will Rule the Future. New York, NY: Penguin Group (USA), Inc. Stein, M. K. & Nelson, B. S. (2003). Leadership Content Knowledge. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25 (4), 423-448. Tapscott, D. (2009). Grown Up Digital. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Wagner, T. (2008). Rigor Redefined. Educational Leadership, 66(2), 20-24. Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005) Understanding by Design (Exp. 2nd Edition). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Electronic Resources Partnership for 21st Century Skills (2002). Learning for the 21st Century. Available: http://www.21stcenturyskills.org/images/stories/otherdocs/p21up_Report.pdf Ministry of Education Singapore (2005). Teach Less, Learn More. Available: http://www.moe.gov.sg/cluesky/tllm.htm. Ministry of Education Singapore (2008). Press Release: More Support for School's "Teach Less, Learn More" Initiatives. Available: http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/2008/01/more-support-for-schoolsteach.php APPENDIX 1 21st Century Learning Skills Information and Communication Skills Thinking and Problem-Solving Skills Interpersonal and Self-Directional Skills Information and Media Literacy Skills Analyzing, accessing, managing, integrating, evaluating and creating information in a variety of forms and media. Understanding the role of media in society. Communication Skills Understanding, managing and creating effective oral, written and multimedia communication in a variety of forms and contexts. Critical Thinking and Systems Thinking Exercising sound reasoning and making complex choices, understanding the interconnections among systems. Problem Identification, Formulation and Solution Ability to frame, analyze and solve problems. Creativity and Intellectual Curiosity Developing, implementing and communicating new ideas to others, staying open and responsive to new and diverse perspectives. Interpersonal and Collaborative Skills Demonstrating teamwork and leadership; adapting to varied roles and responsibilities; working productively with others; exercising empathy; respecting diverse perspectives. Self-Direction Monitoring one’s own understanding and learning needs, locating appropriate resources, transferring learning from one domain to another. Accountability and Adaptability Exercising personal responsibility and flexibility in personal, workplace and community contexts; setting and meeting high standards and goals for one’s self and other; tolerating ambiguity. Social Responsibility Acting responsibly with the interests of the larger community in mind; demonstrating ethical behavior in personal, workplace and community contexts. APPENDIX 2 Brief description of Teach Less, Learn More Source: Ministry of Education Bluesky website: http://www3.moe.edu.sg/bluesky/tllm.htm#tllm1 What is Teach Less, Learn More? Teach Less, Learn More is about teaching better, to engage our learners and prepare them for life, rather than teaching more, for tests and examinations. Remember why we teach Reflect on what we teach Reconsider how we teach • TLLM aims to touch the hearts and engage the minds of our learners, to prepare them for life. It reaches into the core of education - why we teach, what we teach and how we teach. • It is about shifting the focus from “quantity” to “quality” in education. “More quality” in terms of classroom interaction, opportunities for expression, the learning of life-long skills and the building of character through innovative and effective teaching approaches and strategies. “Less quantity” in terms of rote-learning, repetitive tests, and following prescribed answers and set formulae. • Teachers, school leaders and MOE all have important roles to play to make Teach Less, Learn More happen. It calls on everyone of us to go back to the basics • Thinking Schools, Learning Nation (TSLN) was adopted as the vision statement for MOE in 1997. It continues to be the over-arching descriptor of the transformation in the education system, comprising changes in all aspects of education. These changes articulate how MOE would strive toward the Desired Outcomes of Education (DOEs). • Since 2003, we have focused more on one aspect of our DOEs, i.e. nurturing a spirit of Innovation and Enterprise (I&E). This will build up a core set of life skills and attitudes that we want in our students. It promotes the mindsets that we want to see in our students, teacher, school leaders and beyond. • TLLM builds on the groundwork laid in place by the systemic and structural improvements under TSLN, and the mindset changes encouraged in our schools under I&E. It continues the TSLN journey to improve the quality of interaction between teachers and learners, so that our learners can be more engaged in learning and better achieve the desired outcomes of education. The relationship between TSLN, I&E and TLLM is shown in Figure 1 below. To Remember Why We Teach • We should keep in mind that we do what we do in education for the learner, his needs, interests and aspirations, and not simply to cover the content. • We should encourage our students to learn because they are passionate about learning, and less because they are afraid of failure. • We should teach to help our students achieve understanding of essential concepts and ideas, and not only to dispense information. • We should teach more to prepare our students for the test of life and less for a life of tests. To Reflect on What We Teach • We should focus more on teaching the whole child, in nurturing him holistically across different domains, and less on teaching our subjects per se. • We should teach our students the values, attitudes and mindsets that will serve him well in life, and not only how to score good grades in exams. • We should focus more on the process of learning, to build confidence and capacity in our students, and less on the product. • We should help the students to ask more searching questions, encourage curiosity and critical thinking, and not only to follow prescribed answers. To Reconsider How We Teach • We should encourage more active and engaged learning in our students, and depend less on drill and practice and rote learning. • We should do more guiding, facilitating and modelling, to motivate students to take ownership of their own learning, and do less telling and teacher talk. • We should recognise and cater better to our students’ differing interests, readiness and modes of learning, through various differentiated pedagogies, and do less of ‘one-size-fits-all’ instruction. • We should assess our students more qualitatively, through a wider variety of authentic means, over a period of time to help in their own learning and growth, and less quantitatively through one-off and summative examinations. • We should teach more to encourage a spirit of innovation and enterprise in our students, to nurture intellectual curiosity, passion, and courage to try new and untested routes, rather than to follow set formulae and standard answers. It calls on everyone of us to go back to the basics, to Remember Why We Teach More… Less… For the Learner To Rush through the Syllabus To Excite Passion Out of Fear of Failure For Understanding To Dispense Information Only For the Test of Life For a Life of Tests Reflect on What We Teach More… Less… The Whole Child The Subject Values-centric Grades-centric Process Product Searching Questions Textbook Answers Reconsider How We Teach More… Less… Engaged Learning Drill and Practice Differentiated Teaching ‘One-size-fits-all’ Instruction Guiding, Facilitating, Modelling Telling Formative and Qualitative Assessing Summative and Quantitative Testing Spirit of innovation and enterprise Set Formulae, Standard Answers Appendix 3 Training plan for teachers in a Secondary School (grades 7-10)- Teaching the 21st Century Learner The following is a year-long training plan for teachers in a Secondary School in Singapore. The platforms for training are one-hour slots at alternate monthly staff (faculty) meetings (i.e. 5 one-hour slots, excluding June and December when there are no staff meetings) and separate lunch-time small group discussions with about 10 teachers each on a monthly basis (i.e. 10 one-hour small group discussions). Big Ideas Following from the Teach Less, Learn More movement (summary at Appendix 1), the training plan is designed to help teachers remember why they teach, reflect on what they teach, and reconsider how they teach. The big ideas behind the plan are Relationships, Relevance and Rigor (see Scope and Sequence below). The 3 Rs here present a comprehensive framework to view the essential work of schools in facilitating the learning of 21st Century learners. Relationships is put first because it forms a firm foundation for the beginning of the school year as teachers seek to build the conducive learning environments at the start of the year. Before moving on to Rigor, Relevance is explored as the question of what to teach must precede how to teach. As a broad sweep of the different issues related to teaching the 21st Century Learner, the first year training plan is not meant to help teachers learn all there is to learn about best practices in 21st Century teaching, but rather to build an initial awareness of important issues. The training plan will be followed up in the second year with in-depth training in using Understanding by Design as a framework for redesigning curriculum and improving pedagogy and assessment practices. JAN FEB MAR Big Idea: Relationships Establishing a Positive Learning Environment EQs: - What does a positive learning environment look like? - How is the learning environment important in promoting or discouraging learning? Knowing your LearnersLearning Styles EQs: - How do our own learning styles impact how we teach? Differentiating Instruction EQs: - How can we cater to different learning styles and promote the holistic developme nt of learners? APR MAY JUL Big Idea: Relevance The 21st The Century Digital Learner GeneraEQs: tion - What EQs: does a - How is 21st the Century digital graduate generatio need in n terms of different? Attitudes, - How Skills and does this Knowimpact ledge to their succeed? learning? Teaching the 21st Century Learner/ Digital Natives EQs: - What makes for a relevant curriculum for the 21st Century, digital learner? - How can instruction and assessment cater to 21st century needs? AUG SEP Big Idea: Rigor OCT NOV Putting it together Learning Formative Teaching An with Assessfor deep IntroducUnderstandment understandtion to ing EQs: ing UbD EQs: - What is EQs: EQs: - How do the role of - What How can we know assessevidence we plan our that ment in would we curriculum students learning? need to and lessons have truly - How know that so that our learned? should we our students - Why is change students can learn understandour have with ing assesslearned understandimportant in ment with ing? learning? practices understandto ing? maximize learning? Essential questions Relationships - What does a positive learning environment look like? - How is the learning environment important in promoting or discouraging learning? - How do our own learning styles impact how we teach? - How can we cater to different learning styles? Relevance - What does a 21st Century graduate need to learn in order to succeed? - How is the digital generation different from older generations? How does this impact their learning? - What components should a relevant curriculum in the 21st Century have? - How should instructional and assessment practices be changed to better meet the needs of 21st Century, digital learners? Rigor - How do we know that students have truly learned? - How should assessment practices be changed to better help our students learn? - What evidence would be able to tell us that students have truly understood what they learned? Stage 1- Desired Results (Relevance Unit) Established Goals: All teachers will apply the concepts of Relationships, Relevance and Rigor to planning their long range syllabus, units, lessons, instruction and assessment in teaching their students. Understandings: Essential Questions: Teachers will understand that: 1) students need a positive learning environment and supportive relationships with teachers to succeed. 2) curriculum has to be made relevant to the 21st Century learner. 3) a rigorous curriculum results in students gaining deep understanding of the subjects they study. (the essential questions listed here relate only to the Relevance unit of the training plan.) 1) What does a 21st Century graduate need to learn (in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes) in order to succeed? 2) How is the digital generation different from older generations? How does this impact their learning? 3) To what extent does the current curriculum, instructional and assessment practices meeting the needs of the 21st Century learner and digital generation? Teachers will be able to: 1) apply the knowledge about the 21st Century learner and the digital generation in designing their syllabuses, units, lessons and assessments. 2) reflect on their own existing instructional practices and modify them to meet the needs of the 21st century learner. Teachers will know: 1) the demands that the 21st Century society and workplace place on our learners now. 2) the attitudes, skills and knowledge (ASK) these learners will need to develop while they are in school. 3) the characteristics of the digital generation and the opportunities and challenges these characteristics present for their learning. 4) how the curriculum can address the ASK students need to develop. Stage 2: Assessment Evidence Performance Tasks: Other Evidence: 1) keep a personal reflection journal detailing how what they learned about the 21st Century learner and the digital generation will impact their instructional and assessment practices. 2) demonstrate application of what they learn in one lesson to be observed. 1) Teachers use vocabulary learned about the 21st Century learner and digital generation in their professional conversations. 2) Teachers demonstrate increasing knowledge and application of the concepts of 21st Century learner and digital generation in their unit and lesson plans, and assessments. Stage 3: Learning Plan Learning Activities: Staff Meeting in April: Introduction to the 21st Century Learner and the Digital Generation Teachers view videos on 21st Century Learning Matters: (Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2L2XwWq4_BY&feature=PlayList&p=A719A878ECDCA7 84&playnext=1&playnext_from=PL&index=1 ) and a Vision of K-12 Students Today: (Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_AZVCjfWf8&feature=PlayList&p=A719A878ECDCA784&index=0&playnext=1) Teachers engage in Philosophical Chairs activity in 4 groups of 20 (each facilitated by a Principal or Assistant Principal and scribed by a Head of Department) on the topics: (a) “Technology is a boon to education.”; (b) “We are adequately preparing our students for life in the 21st Century”; (c) “Teachers are adequately prepared to teach for the 21st Century”; and (d) “The current assessment system is the biggest obstacle to21st century teaching and learning” Round-robin Gallery Walk April Small Group Lunchtime Discussion on the 21st Century Learner EQ: - What does a 21st Century graduate need in terms of Attitudes, Skills and Knowledge to succeed? Pre-reading: Part 2 of Learning for the 21st Century Report In Groups of 4, teachers quickly review their reading and take down notes on 1 of the 4 following areas: (a) 21st Century Learning skills (b) 21st century tools to develop learning skills (c) 21st century content (d) 21st century assessment After reading and taking notes, teachers will share round-robin. Wrap-up discussion: 3 things I have learned that I can apply in my instructional/ assessment practices. Homework: Reflections May Small Group Lunchtime Discussion on the Digital Generation EQs: (a) How is the digital generation different? (b) How does this impact their learning? Concept attainment activity comparing Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants Teachers view short video on Grown Up Digital - The Net Generation is Changing YOUR World by Don Tapscott (Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EoqiRRMQ0fs) Discussion on what makes the digital generation different and how this impacts their learning. Homework: Reflections July Small Group Lunchtime Discussion on Teaching the 21st Century Learner/ Digital Natives EQs: - (a) What makes for a relevant curriculum for the 21st Century learner/ digital native? (b) How can instruction and assessment cater to 21st century needs? (Teachers will be grouped according to the subjects they teach for this discussion). Teachers will study examples of good teaching for 21st Century learners in the following subject areas: (a) Social studies lesson on Sri Lanka using Zombie music video and primary sources (own resource) (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam website available at http://eelam.com/) (for Humanities teachers) (b) Video of literature lesson on prejudice and personal triumph over adversity (for Language teachers) – Yvonne Hutchinson (available at http://www.goingpublicwithteaching.org/yhutchinson) (c) Math lesson(for Math teachers) – the Border Problem as taught by Jo Boaler (Boaler and Humphreys, 2005) (d) Science lesson (for Science teachers)- THINK Cycle (Temasek Junior College, 2007: available at http://www.schoolbag.sg/archives/2007/07/think-cycle-sets-studentsthin.php) Teachers will discuss the lessons presented and how they relate to their earlier learning on the 21st Century learner and Digital Native. Homework: Reflections Teacher Reflections on Relevance Teachers will keep a reflection journal as a record of their learning throughout the 3R Training. After each session, teachers can use the following questions as prompts for their reflections: 1) What new perspectives about our learners have we gained from the session? 2) How well am I catering to the needs of my learners in my current instructional and assessment practices? 3) What, if any, instructional and assessment practices would I change as a result of what I have learned today? Teachers will submit their reflections by email after each session to their Heads of Department the Monday after the session. Rubric for teachers’ personal reflection journals: Criteria No Evidence of Understanding Reflections continue to center on existing (traditional) paradigms of teaching and learning, with no reference to the needs of 21st Century learners. Developing Competence Demonstrates Competence Exceeds expectations Beginning to use vocabulary of the 21st Century learner, with occasional references to ASK that learners need to develop, although reflections still mixed with existing paradigms. Uses the vocabulary of the 21st Century learner consistently and demonstrates a broad and deep understanding of the needs of these learners. Able to articulate the ASK that learners need to develop. Offers original insights into the needs of the 21st Century learners, applying what teacher knows about the “world out there” to the needs of the 21st Century learner. Able to empathize with the learning challenges faced by the 21st Century learner. Reflections continue to center on existing (traditional) paradigms of teaching and learning, with no reference to the needs of digital generation. Resists the use of technology in teaching and learning. Beginning to use vocabulary of the digital generation, indicating an openness to the use of technology even when acknowledging the personal challenges to doing so. Uses the vocabulary of the digital generation consistently and demonstrates a broad and deep understanding of the opportunities and challenges presented by the use of technology. Offers original insights into the challenges and opportunities presented by technology. Offers creative ideas about how technology could be exploited in enhancing teaching and learning. Able to relate personal experiences with technology to meet the needs of the digital generation. No intention to apply Impact on Instructional knowledge of 21st Century learner or digital Practices generation on instructional practices. Able to articulate how existing instructional practices help meet the needs of 21st Century learners and digital generation, without evidence of much change in existing practice. Intention to apply new knowledge gained to changes in instructional practices. Consistently reflects on how the needs of the 21st century learners and digital generation can be better met through changes in instructional practices. Intention to consistently apply new knowledge gained to improve instructional practices. Instructional practices consistently stretch students in the development of 21st Century skills and leverages on technology to create rigorous and engaging lessons. Knowledge of 21st Century Learner Knowledge of Digital Generation Criteria Impact on Assessment Practices No Evidence of Understanding No intention to apply knowledge of 21st Century learner or digital generation on assessment practices. Developing Competence Demonstrates Competence Exceeds expectations Able to articulate how existing assessment practices help meet the needs of 21st Century learners and digital generation, without evidence of much change in existing practice. Intention to apply new knowledge gained to changes in assessment practices. Consistently reflects on how the needs of the 21st century learners and digital generation can be better met through changes in assessment practices. Intention to consistently apply new knowledge gained to improve assessment practices. Assessment practices consistently stretch students and require them to demonstrate competence/development of 21st Century skills. Leverages on technology in assessment practices. Rubric for lesson observation (teachers’ competencies are gauged on multiple observations so as to get a more accurate picture of teacher performance) Criteria Teaching 21st Century Learning Skills No Evidence of Application No attempt is made to incorporate 21st Century learning skills to teaching. Emphasis in lessons is on rote learning and memorization. Students do not have opportunities to learn or demonstrate any of the skills. Developing Competence Demonstrates Competence Exceeds expectations Teacher makes piecemeal attempts to incorporate 21st Century learning skills to teaching. Most of the lesson still focuses on rote learning of content but occasional opportunities are available to students to pick up the skills incidentally, either through the learning activities or assessments. Teacher makes explicit references to 21st Century Learning skills in teaching the content. Learning activities that give students opportunities to develop the skills are regularly interspersed with delivery of content. Assessments require students to demonstrate some learning of these skills. Students are taught explicit 21st Century learning skills (thinking/problem solving, communication, selfdirectional/ interpersonal skills) in the context of their subject content. Learning activities give ample opportunities for students to develop these skills (e.g. cooperative learning activities to develop interpersonal skills, classroom discourse that promotes critical and creative thinking). Assessments also require students to demonstrate mastery of these skills. Criteria Adapting Content to 21st Century Needs No Evidence of Application Content is taught as standalone knowledge and no effort is made to help students see the relevance of content to real world contexts. Assessments focus entirely on students’ ability to rote learn content without any need for them to apply their learning. Incorporating There is no evidence of the use of technology in Technology the lesson at all. Teacher prefers to use textbooks, worksheets and whiteboards solely for their lessons. Developing Competence Demonstrates Competence Exceeds expectations Teacher consciously tries to adapt content to real world contexts, using occasional examples where possible to help students see the real world relevance of what they are studying, although the links may not be communicated well enough for students to transfer their learning effectively. Assessments continue to focus on students’ ability to rotelearn. Learning activities are consciously related to 21st Century real world contexts. Lessons give opportunities to students to develop one of global awareness, financial, economic and business literacy, and civic literacy. Assessments require students demonstrate these competencies in addition to requiring them to demonstrate mastery of content. Learning activities constantly relate content to 21st Century workplace, home or community needs, allowing opportunities for students to transfer learning to real world contexts. Content is adapted to reflect the global awareness, financial, economic and business literacy, and civic literacy required for learners to thrive in the 21st Century. Assessments also require students to demonstrate these competencies in the context of their subjects. Teacher is beginning to use some simple technology in presentation of lessons, e.g. using Powerpoint, although there is no/marginal leverage on the technology to increase engagement or enhance the effectiveness of the lesson, e.g. Powerpoint is an electronic whiteboard notes. Teacher constantly uses different technological media to enhance the engagement and effectiveness of the lesson. Students enjoy the opportunities to learn in ways that they are used to, e.g. using Internet to do selfdirected research and seek out primary sources, etc. Technology is however not leveraged to create a social network of learners and learning is still largely teacher-directed. Leverages on technology to engage digital natives. Learning skills and ICT tools are seamlessly integrated in learning activities to improve students’ ICT literacy as well as 21st century skills (thinking/problem solving, communication, selfdirectional/ interpersonal skills). ICT creates a social network of motivated learners who see ICT as an enabler for learning.