Capstone Essay_Ruoqin Wang

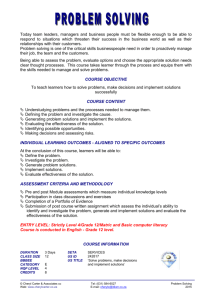

advertisement

1 CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang TESOL Standards for Adults and College English Curriculum Requirements in China Ruoqin Wang Vanderbilt University 2 CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang Abstract In this capstone essay, I will compare College English Curriculum Requirements (Department of Higher Education of MOE of P.R. China, 2007) and Standards for ESL/EFL Teachers of Adults (TESOL Inc., 2008). Factors leading to similarities and differences between the two will be analyzed and presented. This comparative study will result in informed suggestions for the Chinese standard to better facilitate college English curriculum reform in China. These suggestions are based on selected ideas from the TESOL standard that are also applicable to the Chinese context. The TESOL standard is appropriate to compare with the Chinese standard because it aims at helping ESL/EFL teachers worldwide to achieve professional excellence, including Chinese college English teachers. The major focus of this essay is a critical discussion of three shared elements in the two standards: the learner, content, and assessment. Discussions from these three areas lead to the major findings of this capstone essay: (1) the differences between the Chinese standard and TESOL standard can be explained by the specific linguistic and sociocultural contexts from which they developed; (2) the similarities between the two reflect the fact that they are both derived from a broader TESOL context; (3) and there are potentially beneficial ideas from the TESOL standard that can be used to improve the Chinese standard after a careful consideration of the first two findings. Keywords: CECR, SETA, TESOL, standards, comparison 3 CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang TESOL Standards for Adults and College English Curriculum Requirements in China In this capstone essay, I will compare two sets of standards developed for teaching English as a foreign language (EFL). One is the Standards for ESL/EFL Teachers of Adults developed by TESOL International Association in the US, and the other is the College English Curriculum Requirements in China. After introducing the development and structure of the two standards, I will compare them in terms of the three interrelated components of an EFL curriculum: the learner, content, and assessment. I will do this by identifying relevant information from different parts of both documents. Discussion based on comparison results focus on (1) exposing the theoretical or ideological foundations consciously or unconsciously employed by the two sets of standards, (2) analyzing special characteristics and needs of China’s college English teaching in the broader ESL/EFL context, and (3) making recommendations for implementers and developers of the Chinese standard, primarily by “borrowing” from the TESOL standards. Rationale EFL education in China is undergoing reform to keep up with China’s overall development and globalization (Zuo, 2008). In 2007, the Chinese Department of Higher Education revised its curriculum requirements of teaching college English (called CE hereafter) to its newest version, the College English Curriculum Requirements (called CERC hereafter) (Department of Higher Education of MOE of P.R. China, 2007). Meanwhile, curriculum requirements that developed out of EFL contexts such as the Standards for ESL/EFL Teachers of Adults (called SETA hereafter) (TESOL Inc, 2008) are aimed at supporting teachers worldwide, which I will compare with CERC in my capstone essay. 4 CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang The results of the current study will possibly help CE teachers who are using CECR to develop a deeper understanding of this document, especially some of its limitations. This is because comparing and contrasting language teaching standards based on different theoretical frameworks, historical developments, and sociopolitical perspectives can make the characteristics of either of the standards more salient to readers. On the other hand, this paper is also written for developers of CECR with suggestions for a better facilitation of the ongoing CE education reform in China. Here I will also need to elucidate why I choose to compare CECR with SETA. To begin with, foreign language education in the US has witnessed huge improvement since the introduction of Standards for Foreign Language Learning: Preparing for the 2lst Century developed by the American Council on The Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) (Zhou & Zhang, 2007). Therefore, a lot of English teachers in China, especially those in elementary and middle schools have made efforts to draw ideas from the ACTFL standard which are believed constructive for English teaching in China (Xiao, 2002; Zhou and Zhang, 2007; Kang, 2011 etc.). Compared with the ACTFL standards, SETA is developed exclusively for teaching English to an age group that is more aligned with CECR, which justifies the attention paid to SETA in this paper. CECR and SETA are both developed for adult learners. Another reason for selecting SETA is the fact that it is well grounded in theories after wide consultation of TESOL experts around the world (Gao, 2009). Therefore, it is highly possible some theory-informed teaching principles in SETA will be applicable to CE education in China as well. Introduction of Two Standards CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 5 The SETA is a 187-page book developed with the mission of ensuring excellence in English language teaching to speakers of other languages. It tries to answer this question for teacher candidates in the TESOL profession: What is effective teaching? The main audience of this book would be teachers, teacher trainers and administrators (SETA, p. vii). On the other hand, the CECR is a concise document for teaching English to non-English majors in colleges in China. Pursuing higher teaching quality is only one of the many objectives of this document as it was developed with a view to “…keeping up with the new development of higher education in China, deepening teaching reform, improving teaching quality, and meeting the needs of the country and society for qualified personnel in the new era.” Even though CECR does not identify its targeted audience at the beginning, I would argue that college teachers, administrators as well as students are all presumed readers. Development The SETA. SETA for ESL/EFL is developed by the global association of TESOL as part of a series of standards for ESL/EFL teachers. It was originally developed for teachers of adult ESL learners in the US back in 1999. Based on research and feedback from professionals, TESOL realized the applicability of this set of standards outside of the US and revised it for teachers from diverse backgrounds including workplace, college, intensive English Programs (IEPs) and EFL programs (SETA, p.vi). The CECR. CECR came in effect in 2007 and is currently used for China’s CE education. Before that, the CE teaching standards in China have gone through several times of revision and reform. In 1986, College English Syllabus (CES) was published for the first time as a nation-wide framework of standards for CE teaching. The required areas of teaching CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 6 listed in the syllabus are pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar, reading, listening, writing and speaking. Among them, reading is decided to be the primary focus of college English teaching (Ruan& Jacob, 2009) yet basic requirements for all seven areas are forced upon every college to achieve (Cai & Xin, 2009). The syllabus was not given modification until the year of 1999, the turn of the century, when it was revised to stress only the four basic skills, reading, listening, writing and speaking. Then in March 2004, the Syllabus was replaced by the College English Curriculum Requirements (CECR) in response to the Project of Improvement and Transformation of Curriculums of Higher Education initiated by the Ministry of Education (Ruan & Jacob, 2009). In CECR (2004), colleges are given the freedom to create their own syllabi with reference to CECR. The 2004 version of CECR is actually a pilot edition. When the 2007 version of CECR came out, colleges are given further freedom to modify the teaching requirements in the light of their own resources and needs (Cai & Xin, 2009). Structure The SETA. The standards in SETA are organized under eight topics: Planning, Instructing, Assessing, Identity and Context, Language Proficiency, Learning, Content and Commitment and Professionalism. In order to set forth clear guidelines for ESL/EFL adult teachers, SETA follows this format of presenting each individual standard: description of the standard, theoretical justification of it, performance indicators showing desired learning performances and well-structured illustrations called vignettes showing the standard being implemented in real classrooms. Since SETA aims at offering effective teaching principles that can be immediately helpful for classroom teachers (SETA, p. v), each standard consists 7 CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang of sub-standards that are performance-based and organized by bulletin points. One example would be “ uses a variety of formal and informal assessment tools appropriate for the context and desired results”. Appendix A and C of the book list some resources as extensions of the theoretical justification that is explained within each standard. Those are academic articles on which the development of the book is based and a recommended reading list of similar articles. Appendix B offers a guide for self-review for teachers. The CECR. As a comprehensive guiding manual for each department of college English teaching and learning, CECR is not as dedicated as in giving classroom teaching suggestions. It first briefly introduces the characters and objectives of college English in China. Then, the Teaching Requirements section sets up three English proficiency levels that would be achieved by college students upon graduation. From basal to ceiling, the levels are basic, intermediate and advanced. Within each level, there are detailed descriptions of learner performances presented as teaching goals in the areas of listening, speaking, reading, writing, translation and vocabulary. Required performances in each skill area are as detailed as how many words learners at each stage have to process during listening per minute. The following parts are Course Design, Teaching Model, Evaluation and Teaching Administration. In Appendix A, a detailed explanation of computer-based teaching is supposed to guide teachers through the building of this model while in Appendix B, recommended protocol for self/peer-assessment given for students’ reference. Critical Comparisons CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 8 In this section, I am going to compare the standards in learner, content and assessment. It should be noted that I do not aim at acquiring an exhaustive list of differences and similarities between the two standards in those three areas. For example, for the following discussion on the learner, I will put emphasis on how the two standards address learner differences and perceive independent learning. Learner SETA and CECR both pay attention to the role the individual plays in choosing appropriate teaching approaches and building effective teaching models. Using learners’ own insights and preferences to inform learner education can be traced to the learner-centeredness movement in TESOL, which has a central focus on learner autonomy (Tudor, 1996). The SETA. SETA asks teachers to use a variety of strategies and activities to address individual differences (SETA, p. 24). Different kinds of learner characteristics are addressed in SETA: learners’ interests, needs, prior learning, background knowledge, identities, roles, communities, English level, first language, rates and styles of learning and expertise in content areas (SETA, p.4; p. 66; p.102; p. 121). In terms of attitudes toward those learner traits, SETA stipulates that teachers employ them as classroom resources while helping student develop appreciation toward each other (SETA, p.66). On the other hand, leaners should be encouraged to engage in decision-making about their learning with a long-term goal to become independent, lifelong learner (SETA, p.24). Autonomy, which is defined by Benson (2001) as the ability to take control of one’s learning, is advocated in SETA and described as something that can be trained through carefully designed instruction (SETA, p.102). CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 9 The CECR. With learning-centeredness as one of its primary theoretical bases (Ruan and Jacob, 2009), CE reform in China as well as the newest version of CECR (2007) values individual learners, promoting a shift from the traditional teacher-centered model (CECR, Teaching Model). Learner characteristics as well as the type of college are called into attention in CECR to meet CE’s need of individualized teaching, a proposed response to the challenge of colleges scattering around a large country (CECR, Teaching Requirements). As a result, teachers should be mindful of the following things during instruction and assessment: learner aptitude, initial language competence, college status, types, education goals and college resources (CECR, Teaching Requirements; Teaching Model). Meanwhile, CECR encourages the students to engage in individualized learning to meet their own needs in different specialties (CECR, Course Design). Unlike SETA, in which collaboration among learners is valued (SETA, p.102), CECR has a salient priority for learners to be independent without mentioning collaborative learning. Specifically, it asks students to decide which materials and methods to use based on their own needs with the ultimate goal of being proficient in autonomous learning, which is possible to be developed under the guidance of obtained learning strategies (CECR, Teaching Model). Discussion. The first step in designing a curriculum is to consider who are the learners. Both standards ask teachers to adapt their teaching to cater to individual differences. Relatively speaking, SETA proposes a longer list of learner-related factors for teachers to consider. Interesting enough is the fact that it is SETA but not CECR that calls into attention learners’ L1 and identity. In SETA, these two factors can actually be used to show the distinct sociocultural underpinnings of the two sets of standards. On the other hand, it is also CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 10 interesting to notice that SETA and CECR both set up the goal of cultivating lifelong, autonomous learners, which reflects a possible influence from the broader TESOL world, the fashionable concept of learner-centeredness. L-1 and Learner Identity. Since 1980’s, the popularity of monolingualism and its dominance in the theories of language education allows its influence to extend from ESL to EFL countries (Song, 2009). It is not until recently that more and more evidence from different perspectives is emerging to justify the positive side of using of L1 in L2 teaching (Atkinson, 1987; Atkinson, 1993; Duff & Polio, 1990; Cummins, 1996 etc.). However, it seems reasonable for CECR not to advocate using L1 in class as there is already much less exposure to the English language outside of EFL classrooms compared with those in English-speaking countries (Duff & Polio, 1990; Polio & Duff, 1994). Moreover, there are negative sociopolitical implications of using English exclusively in the schools of some ESL countries (Auerbach, 1993). Pedagogically speaking, many researchers have examined classroom languages in ESL classrooms, yet relatively few have characterized FL classes (Polio & Duff, 1994). They may be the reasons why SETA treats L1 more seriously. In a similar vein, studies concerning identities of English learners tend to focus predominantly on immigrant learners’ learning experiences in their host countries while few studies are targeted at EFL learners in their homeland countries (Gu, 2010). This is probably the reason why identity cannot be found in CECR. The ESL teaching setting in the US is what SETA was originally designed for. It is highly likely that the culturally heterogeneous nature of that teaching context calls for a subtler sociocultural understanding of the learner than the Chinese context. CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 11 Independent Learning & Autonomy. Both standards expect their students to become autonomous, lifelong learners. While SETA values both individual and collaborative learning, CECR has explicit requirements only for independent learning. My conclusion about this distinction is that the worldwide call for a transition from the teacher-centered to learners-centered classroom may have triggered different reactions between the developers of CECR and those of SETA. Holliday (2005, p.83) contends that there is a tendency in education to try to let people develop cultural behaviors they were not born into. Therefore, the dependent disposition usually associated with learners born into Confucius cultures are polarized against words such as “independent,” “decision-making” and “autonomy” when such western originated ideas are introduced into these different cultures. Given that there is a teacher-guided tradition in EFL teaching in China (Anderson, 1993; Jin & Cortazzi, 1998; Braine, 2003 etc.), the rationale for CECR to prefer independent learning over a mixed approach is probably to remold that widely adopted teaching style toward a more learner-centered one. The underlying assumption is probably that “dependent” learners cannot make “qualified personnel in the new era” as desired in the opening statement of CECR. As is put forward by Ruan and Jacob (2009), one of the theoretical foundations of CE reform is “…to counter the passivity that is enemy of true learning, students need to develop their own strategies to become automatic learners….” Two things are problematic here. Firstly, any empirical evidence can show that those “passive learners” can also be engaged in true learning. Secondly, they fail to take into account the assumed passivity before asking students to develop strategies on their own, which reflects the difficulty involved in efforts to change deeply entrenched culture. Therefore, CE reform in China along with CECR, CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 12 the guiding document of that reform, should be cautious of the pitfalls of promoting learner-centeredness. Content In this part, I will focus on how SETA and CECR perceive the relationship between content and language learning, which would be a central element in a language teaching curriculum since it bears heavily on the instruction, assessment, material and teacher training. From the learners’ perspective, learning goals sometimes have to be negotiated with the content being taught in language classes. The following analysis serves the purpose of exposing factors underlying the different content requirement in SETA and CECR as well as evaluating CECR’s intention to provide appropriate learning content for CE students. The SETA. Content teaching in SETA is described as the teaching of communicative competence in a certain content area, which involves the teaching of grammatical, discourse, sociocultural and strategic competence (SETA, p. 119). In line with this definition of content, pedagogical and real-world tasks are both needed for teaching content (SETA, p. 121). SETA defines very clearly the teacher’s role in teaching content with specific pedagogical suggestions. During preparation, “Teachers may need to inform themselves about the language associated with the content areas that their students want to learn about.” (SETA, p. 120). In class, there is an emphasis on scaffolding students in that teachers need to provide “both oral and written language in the content area” and “the linguistic features of the content-related language” (SETA, p.121), which is called by Ferguson (1997) as the knowledge of genre and discourse in content teaching. Coping strategies also need to be taught when other communicative competencies are not developed well enough to acquire CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 13 content. Out of class, there is a requirement for teachers to “collaborate with content specialists to develop lessons” (SETA, p. 121). SETA’s comprehensiveness in addressing the different aspects of content teaching reflects to a certain degree the teaching context it draws theoretical underpinnings from. At this moment, an analysis of how CECR perceives content in English teaching might confirm my position that the two sets of standards under study are derived from distinct social and cultural environments. The CECR. Relative to SETA, CECR has a less structured content requirement. In its Teaching Requirement part, SETA does not address content adequately because only the requirements for listening and reading imply to a certain degree the content to be taught. In its performance criterion for listening, CECR requires learners to be able to understand English radio and TV programs. For reading, learners are required to read English newspaper and magazines on familiar topics and textbooks in the area of their specialty. It is clear that teacher’s role in content teaching is far from specified. Meanwhile in a vague way, the Course Design section of CECR requires teaching content to be related to students’ specialties by building a course system that encompasses not only general English courses but also courses in “language and culture” and “English of specialty” with the purpose of to cultivating students’ cultural awareness and communicative ability (CECR, Course Design). Discussion. Content-based instruction has been touted as effective in a wide range of educational contexts (Cummins, 1980; Snow, Met & Genesee,1989; Byrnes, 2002; Cammarata, 2009 etc.). In China, the development of courses for non-English majors CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 14 categorized as English for Special Purpose (ESP) is argued by many to have great potential in enhancing CE reform (Fan, 1995; Cammarata, 2009;Cai, 2010 etc.). In line with this movement, College English Syllabus (1999), the predecessor of CECR first brought attention to the importance of teaching English for professional development (Cai & Xin, 2009). However, the feasibility of this intention is questionable. First, even CECR (2007), the newest CE curriculum requirement is very vague about the approaches to promoting content-based curriculum. Apart from asking colleges to build a comprehensive course system, which few colleges in China have done so far, CECR “…encourage(s) students’ individualized learning so as to meet the needs of their development in different specialties.” In other words, CECR fails to specify the role of teachers in teaching content or implementing the recommended course system. On the contrary, SETA is clearer about the nuances of implementing content-based teaching as evidenced by its comprehensive pedagogical suggestions. A possible historical connection is that in US schools and colleges, subject areas are taught in English, which leads to a more comprehensive pedagogical framework supported by adequate ESL content-teaching resources and researches. Therefore, it might benefit CECR developers to provide guidelines as clear as those in SETA in their next step of promoting ESP. They should also remain cautious of the possible challenges arising from limitations of resources in their specific contexts because SETA may be too broad to address the specific needs of any single country. Assessment and Evaluation Assessment is attached with great importance in both SETA and CECR. SETA uses CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 15 Standard 3: Assessing to provide teachers with guidelines in assessing learners. Meanwhile, assessment information can be found in CECR’s Evaluation section and the self-peer assessment rubric in the Appendix. To have a more informed discussion later, it is better to take a look at the most influential college English test for non-English majors in China. CET is short for College English Test. It consists of CET Band 4 and 6 and is required for non-English majors in China, which has participants of around 10 million every year. They are primarily summative assessments yielding quantifiable examination results (Xiong & Xiao, 2012). A pass in CET Band 4 is one of the prerequisites for college students to get a Bachelor’s degree or an undergraduate diploma (Cai & Xin, 2009). CET is characterized by the predominance of multiple-choice questions (Han, Dai & Yang, 2004; Liu, 2007) and lack of mandatory speaking test (Gu & Liu, 2005). Theses are good reasons to question CET’s validity in assessing the ability to use English. On the other hand, CET has such merits as objectiveness and a wide coverage of English knowledge (Gu & Liu, 2005). The SETA. SETA advocates the use of “multimodal, systematic and purposeful” assessment tools (SETA, p. 44). Specific types of assessment include those“…that are instructor generated and standardized” as well as “…a variety of formal and informal assessment tools…(SETA, p. 44).” Whatever assessment tool is used, the goal is to evaluate the ability of students applying “acquired knowledge and skills in realistic contexts” (SETA, p. 43). In SETA, teachers are stipulated to examine test quality as part of their responsibility in administrating tests. They should be able to know the advantages and disadvantages of CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 16 different types of assessments. All types of assessments should be “instructor generated and standardized” for the consideration of validity and reliability. In that regard, cultural sensitivity is also one element to be examined by teachers (SETA, p. 43). The CECR. In CECR, a comprehensive system of assessment consisting of both formative and summative assessments is recommended for everyday teaching. Manifestations of formative assessments can be self-assessment, peer assessment and those conducted by teachers and administrators (CECR, Evaluation). There is a detailed rubric for self/peer assessment containing requirements for listening, speaking, reading, writing and translating in the Appendix. This rubric aims at helping students monitor their learning on a regular basis (CECR, Evaluation), which corresponds to the Requirement’s goal to promote independent learning. Summative tests should include final tests and proficiency tests. It is articulated that apart from reading, writing and translating, listening and speaking should also be tested in summative tests because the goal is to assess students’ all-around communicative competence (CECR, Evaluation), which probably reflects an underlying wish to improve CET. Discussion The absence in CECR of asking learners to be assessed in “realistic contexts” probably reveals the unfamiliarity with teaching English for real-life problem solving in China’s English education. It seems unrealistic to include tasks in CE assessments such as an oral interview for the citizenship exam or writing a resume, which are listed in SETA as real-world tasks in Standard 7: Contend (SETA, p.120). Instead, it sets up the goal of assessing communicative ability yet still fails to define that in a pedagogically constructive way. What is communicative competence? To answer this question, people have to bear in 17 CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang mind that different cultures have different connotations and expectations for being communicative (Chowdhury, 2003). Similarly, Holliday (2005, p. 155) points out the differences between the way communicative is interpreted between western countries where Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) originated and EFL countries where cultural factors often arguably hinder the application of “standard” CLT (Holliday, 2005, p.144). Based on those arguments, I think it is appropriate to contemplate further what should be assessed for CE students in China based on their sociocultural contexts and learning objectives. If the students do not all need to deal with real-life tasks in English after they graduate, the question remains what the English tests in College should assess. If that is communicative ability, what are the contexts to assess this ability? Given that there is lack of generally accepted measures of communicative competence in China (Liu, 2007), answering those questions may help CE to solve that problem. Another difference is the level of attentions paid to the quality of tests. CECR does not ask the teachers to take an active role in examining the validity and reliability of assessments as SETA does. One possible explanation is that traditionally English teachers in China are not accustomed to examining the standardized tests they are assigning to test students. However, national standardized tests such as CET are not perfect regarding reliability and validity, a problem which is catching more and more attention in China (Yang & Weir, 1998; Han, Dai & Yang 2004; Gu & Liu, 2005; Wang, 2010). Therefore, it seems appropriate to entitle CE teachers to evaluate the quality of tests as well. General Discussion There are two underlying assumptions in my previous discussions on the learner, CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 18 content, and assessment. The first is that language standards are not born in a vacuum. Nunan (2007) has put forward that every standard contains some ideological imprints unique to a particular social and cultural context (Nunan, 2007). SETA, which was drafted first for ESL teachers in the US and then revised to be applicable to the international setting, remains ESL-oriented in many of its expectations and methodologies. Of the 40 vignettes in SETA, 28 are set in the United States (Gao, 2009), which leads to questions of the validity of using SETA in a particular EFL country with different linguistic and sociocultural realities. Nonetheless, one success of SETA is its relative transparency in presenting theoretical foundations, which allows readers to dig deeper into the rationale behind SETA’s positions. In CECR, the absence of theoretical justifications may undermine its potential to be used in colleges of great diversity around China. At the same time, attention should also be paid to the shared ideas in the two standards. For example, CECR asks students to select materials and methods on their own and engage in independent learning related to their specialties. They are manifestations of a certain type of autonomy that is usually discussed in western literature, which is known as the “proactive autonomy” (Littlewood, 1999). On the other end is “reactive autonomy” where teachers initiate the direction for students to engage in autonomous learning and this seems to fit the expectations for “dependent eastern learners” better. Even though it is masking individual differences to assume that Chinese students are more likely to accept autonomy on the reactive end, CECR, as a national standard, may need to improve the way it promotes autonomy to be more context-sensitive. My second assumption is that CECR development would benefit from “borrowing” CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 19 because an idea with its ideological origin in the English-speaking western TESOL does not mean it would be inappropriate in other contexts. Well-conceived adaptations are needed for CECR to reconcile some potentially constructive pedagogical practices from standards developed in other contexts such as SETA. Earlier in this essay, SETA’s stress on L1 use and learner identity has been used to expose embedded social and ideological differences. However, L1 is not irrelevant to EFL as the use of L1 in EFL classrooms is unavoidable (Song, 2009; Duff & Polio, 1990), and proper use of it entails desired learning results (Cook, 2001; Turnbull, 2001; Duff & Polio, 1990; Atkinson, 1987 etc.). In fact, based on CECR’s suggestion of building course systems that integrate subject learning with English learning, I predict that L1 use will become more attractive and popular in the future. In the process, CECR development may benefit from referring to literatures developed in ESL countries with a concurrent aim to accommodate CE’s needs in making recommendations for using Chinese. The same can be said with identity. The language classroom is the place where teachers and students are involved in identity reconstruction (Colins and Blot, 2003). With China’s increasingly important status, it has become critical for Chinese college students to resolve the contradictions between how they view themselves and stereotypes from the outside (Duff & Uchida, 1997) as well as to reconcile their “China identities” and “global identities” (Gu, 2010). These are reasons for CE to bring in the discussion of identity. Although not all ideas in an ESL-based standard reflect western TESOL ideology, standard implementers should still make efforts to achieve a “cultural continuity” (Holliday, 2005, p. 147). This holds true for SETA, an ESL/EFL standard developed in the US. For example, as I have argued above, CE might develop in a direction with more and more 20 CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang collaboration between subject teaching and language teaching. On the one hand, the relatively comprehensive content-based teaching framework presented in SETA might be a good source of reference. On the other hand, China’s institutional culture in education should not be neglected. Bernstein (as cited in Holliday, 1994) proposes two distinct paradigms of professional-academic culture, collectionism and integrationism. The collectionist culture features strong subject boundaries. In contrast, integrationist culture has “blurred” boundaries. China’s education tends to belong to the integrationist model. Therefore, it might seem intimidating to assign colleges with the task of teaching “English of Specialty” (CECR, Course Design), as verified by the current failure of this proposal in CE. The implication for this essay is that as important as introducing to CE educators the content-teaching strategies in SETA, so too is taking into account the readiness of them for accepting those ideas. In sum, it is not problematic for a standard developed in an English-speaking country to be used in various contexts, but it is a serious problem if standard implementers ignore the richness, diversity and dynamism in the context in which it is used. This holds true for CE educators using SETA. Conclusion In this essay, I compared the two standards regarding their perspectives on the learner, content, and assessment and have offered several suggestions for both readers and developers of CECR. The differences between the two are employed not only to show some limitations of using SETA for a specific EFL teaching context but also to reveal a space for reconciliation. Meanwhile, the similarities has shown to a certain degree the broader TESOL context of which CE is a part and led me to consider whether there is a need for CECR to become more CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 21 context-sensitive. In a word, this comparative study would potentially benefit CE educators in China for similar reasons that collaborative development programs would benefit the TESOL profession worldwide. Whether they are referring to CECR or exported standards, they should be mindful of the standards’ theoretical and sociocultural underpinnings and make efforts to decide whether the standards fit the specific teaching contexts. CE developers likewise would benefit from comparative studies of this kind because they will have a deeper understanding of the standard they have developed and generate thoughts about the direction of future improvement. 22 CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang References Anderson, J. (1993). Is a communicative approach practical for teaching English in China? Pros and cons. System, 21(4), 471-480. Atkinson, D. (1987). The mother tongue in the classroom: a neglected resource?. ELT journal, 41(4), 241-247. Atkinson, D. (1993). Teaching monolingual classes. London: Longman. Auerbach, E. R. (1993). Reexamining English only in the ESL classroom. Tesol Quarterly, 27(1), 9-32. Benson, P. (2001). Autonomy in language learning. Harlow: Longman. Braine, G. (2003). From a teacher-centered to a student-centered approach: A study of peer feedback in Hong Kong writing classes. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 13(2), 269-288. Byrnes, H. (2002). The role of task and task-based assessment in a content-oriented collegiate foreign language curriculum. Language Testing, 19(4), 419-437. Cai, J. (2010). Implications of Taiwan's ESP for the Mainland's College English Reform [J]. Foreign Languages and Their Teaching, 6, 007. Cammarata, L. (2009). Negotiating curricular transitions: Foreign language teachers' learning experience with content-based instruction. Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue canadienne des langues vivantes, 65(4), 559-585. Chowdhury, M. R. (2003). International TESOL training and EFL contexts: The cultural disillusionment factor. Australian Journal of Education, 47(3), 283-302. Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom. Canadian Modern Language CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 23 Review/ La Revue canadienne des langues vivantes, 57(3), 402-423. Collins, J., & Blot, R. K. (2003). Literacy and literacies: Texts, power, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cummins, J. (1980). The entry and exit fallacy in bilingual education. NABE journal, 4(3), 25-59. Cummins, J. (2000). Academic language learning, transformative pedagogy, and information technology: Towards a critical balance. TESOL Quarterly, 34(3), 537-548. Cummins, J., & Davison, C. (Eds.). (2007). International handbook of English language teaching. New York: Springer. Duff, P. A., & Polio, C. G. (1990). How much foreign language is there in the foreign language classroom?. The Modern Language Journal, 74(2), 154-166. Duff, P. A., & Uchida, Y. (1997). The negotiation of teachers' sociocultural identities and practices in postsecondary EFL classrooms. Tesol Quarterly, 31(3), 451-486. Gao, X. (2009). Standards for ESL/EFL Teachers of Adults. TESOL Quarterly, 43 (3), 560-562. Gu, W. & Liu, J. (2005). Test Analysis of College Students’ Communicative Competence in English. Asian EFL Journal, Volume 7, Issue 2. Gu, M. M. (2010). Identities constructed in difference: English language learners in China. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(1), 139-152. Han, B., Dai, M. & Yang, L. (2004). Problems with College English Test as emerged from a survey. Foreign Languages and Their Teaching 179, 17-23. Higher Education Department, Ministry of Education, China. (2004). College English CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 24 curriculum requirements. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press. Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology and social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Holliday, A. (2005). The Struggle to Teach English as an International Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Jin, L., & Cortazzi, M. (1998). Dimensions of dialogue: Large classes in China. International. Journal of Educational Research, 29(8), 739-761. Liu, J. (2007). Developing a Pragmatics Test for Chinese EFL Learners. Language Testing, 2007, 24 (3). Littlewood, W. (1999). Defining and developing autonomy in East Asian contexts. Applied linguistics, 20(1), 71-94. Nunan, D. (2007). Standards-based approaches to the evaluation of ESL instruction. International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 421-438). Springer US. Polio, C. G., & Duff, P. A. (1994). Teachers' language use in university foreign language classrooms: A qualitative analysis of English and target language alternation. The Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 313-326. Ruan, Y., & Jacob, W. J. (2009). The transformation of college English in China. Frontiers of Education in China, 4(3), 466-487. Snow, M. A., Met, M., & Genesee, F. (1989). A conceptual framework for the integration of language and content in second/foreign language instruction. Tesol Quarterly, 23(2), 201-217. Song, Y. (2009). An investigation into L2 teacher beliefs about L1 in China. Prospect. An CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 25 Australian Journal of TESOL, 24(1), 30-39. Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. (2008). Standards for ESL/EFL Teachers of Adults. Alexandria: TESOL Inc. Tudor, I. (1996). Learner-centredness as Language Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Turnbull, M. (2001). There is a role for the L1 in second and foreign language teaching, but…. Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue canadienne des langues vivantes, 57(4), 531-540. Wang, W. (2010). Investigating the Washback Effect of the New CET Listening Comprehension Subtest on Language Learners. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, Vol. 33 No. 5. Xiong, L & Xiao, W. (2012). On Significance on Building Formative Assessment System in College English Teaching. 2012 2nd International Conference on Future Computers in Education. Lecture Notes in Information Technology, Vols 23-24. Yang, H., & Weir, C. (1998). Validation study of the national college English test. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press. Yi, F. (1995). ESP: Reasons for its existence. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 3, 007. Zuo, L. (2008). A recent history of teaching EFL in China. TESOL (Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc.). Essential Teacher, 5(2), 1–6. 蔡基刚, & 辛斌. (2009). 大学英语教学要求的统一性与个性化——关于《 大学英语程 教学要求》修订的思考. 中国外语: 中英文版, 6(2), 4-10. CAPSTONE Ruoqin Wang 26 康璐. (2011). 美国外语学习标准对我国大学外语教学的启示. 青年与社会: 中外教育研 究, (3), 94-95. 肖建芳. (2002). 美国外语教育改革及其启示. 中小学外语教学, 5, 287. 周芬, & 张智华. (2008). 美国外语学习标准与我国英语新课标异同分析及教学启示. 西 华大学学报: 哲学社会科学版, 26(6), 98-100.