Stevens, E. N., Holmberg, N. J., Keeports, C. R., Lovejoy, M. C., Pittman, L. D. (2013, November). A Computerized Measure of Regulatory Strength: Relations to Self-Discrepancies and Depressive Symptoms . Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, Nashville, TN.

advertisement

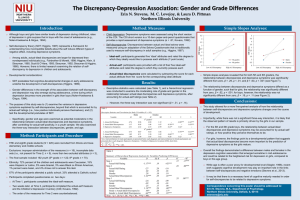

Erin N. Stevens, Nicole J. Holmberg, Christine R. Keeports, M. C. Lovejoy, & Laura D. Pittman Northern Illinois University Self-discrepancy theory (SDT; Higgins, 1987) is a framework for understanding how incompatible beliefs about the self induce different types of negative affect. Discrepancies between the actual-self perception and ideal-self goals are associated with depressive symptoms. Regulatory strength refers to how cognitively accessible self-identified goals are for each individual. Stronger goals (those that are more accessible) are hypothesized to relate to more intense emotional responses following self-discrepancies. Support from (1) self-reported regulatory strength, and (2) response latency measures of regulatory strength (e.g., Higgins et al., 1997). Response latency measures do not account for potential confounding factors (e.g., typing/motor speed, processing speed, impulsive responding). The purpose of this study was to further examine how regulatory strength moderates the association between actual:ideal discrepancies and depression. Extending upon previous work using self-report measures, we utilized a computerized lexical decision task to measure regulatory strength. Used a lexical decision task similar to that of Shah, Brazy, & Higgins’ (2004) task, which to our knowledge, has never been used to examine regulatory strength as it relates to self-discrepancies and their respective negative emotional outcomes. Hypothesis The relationship between actual:ideal discrepancies and depressive symptoms would be moderated by the accessibility (i.e., strength) of idealself goals, even after accounting for processing speed, actual:ought discrepancies, and anxiety symptoms. Participants included undergraduate college students (N = 162) Age range = 18-31 years (M = 19.7 years, SD = 2.06; 52% female) Ethnicity: 59% White, 20% Black/African American, 12% Hispanic/Latino(a), 6% Asian American, 2% Biracial, 3% other/unspecified Measures Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996; α = .88); Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., 1988; α = .91). Self-Discrepancies: Discrepancies between actual and ideal selves were measured using an adaptation of the Selves Questionnaire (Higgins, 1987; Stevens et al., 2013). Participants generated five ‘ideal’ (or ‘ought’) attributes and rated the degree to which they ideally would like to possess each attribute (ideal- or ought-self), and then were provided with a list of the attributes they had previously reported and asked to rate the degree to which they currently possessed each attribute (actual-self). In order to calculated self-discrepancies, the score for each actual attribute was subtracted from the corresponding ideal- or ought-self attribute. Goal Strength: Reaction times (RTs) were calculated for the length of time (in ms) that it took the participants to identify whether a string of letters was a word or non-word; RTs were calculated separately for the (1) control words, (2) ought-self goals, and (3) ideal-self goals, with faster RTs being a proxy for more accessible goals. Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for variables of interest Simple slopes tests: For individuals with relatively stronger ideal-self goals (i.e., faster RTs), were calculated (see Table 1). A regression analysis was conducted to examine ideal-self goal strength as a moderator of the relationship between self-discrepancies and depression (see Table 2). For the analysis, baseline (control) RTs, and actual:ought selfdiscrepancy, anxiety symptoms, and ought-self goal strength were entered as covariates. there was a significant positive association between actual:ideal discrepancies and depressive symptoms (β = .33, p <.01). For individuals with relatively weaker ideal-self goals (i.e., slower RTs), there was not a significant association between actual:ideal discrepancies and depressive symptoms (β = .02, p =.87). Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Variables Variable 1 2 3 4 1. A:I Discrepancy -2. A:O Discrepancy .71*** -3. Control Word Strength .03 .07 -4. Ideal Goal Strength .02 .02 .83*** -5. Ought Goal Strength .01 .07 .86*** .76*** 6. Depression .20* .17* -.02 .00 7. Anxiety .04 .06 -.12 -.14^ M 1.77 1.44 555.90 542.72 SD 1.05 1.08 131.19 127.03 Note. N = 162. A:I = Actual:Ideal; A:O = Actual:Ought. ^p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. 5 -.05 -.06 549.38 138.04 6 7 -.60*** 9.67 7.01 -8.62 8.54 Table 2 Summary of Regression Analyses Examining the Moderating Effect of Goal Strength on Depressive Symptoms Variable β Anxiety Symptoms .59*** Actual:Ideal Discrepancy .17^ Actual:Ought Discrepancy .02 Control Word Strength -.11 Ideal-Self Goal Strength .13 Ought-Self Goal Strength .12 A:I Discrepancy x Ideal-Self Goal Strength 2 -.16* R .42*** F 15.60*** Note. N = 162. ^p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. The lexical decision task seems to be a good proxy for regulatory strength. Findings underscore the importance of considering the role of individual difference factors (e.g., goal-strength) when examining the association between actual:ideal discrepancies and depressive symptoms. The mean RTs for ideal-self goals were significantly less than the mean RTs for the control words; indicates that participants had faster response times to their ideographic ideal-self goals compared to control words. Individuals’ self-identified goals – particularly those associated with the ideal-self – are more chronically activated, as they were more quickly able to identify whether their goals were words compared to other word strings. Results demonstrated a significant interaction between actual:ideal discrepancies and ideal-self goal strength, such that discrepancies were positively related to depressive symptoms, though only for individuals with a stronger regulatory focus (i.e., faster RTs for ideal-self goals) as measured by the lexical decision task. Bolstering previous research that suggests goal strength is a moderator of the discrepancy-depression relationship (Higgins et al., 1997). Findings hold even after controlling for general reaction times and processing speed (as well as anxiety and ought-self constructs). Clinical Implications: Individuals’ goals and their strategies for pursuing these goals (e.g., selfsystem therapy for depression; Vieth et al., 2003) may be a particularly important clinical intervention target for a subset of individuals who present with mood disorders (e.g., Strauman et al., 2006). Correspondence concerning this poster should be directed to: Erin N. Stevens, M.A., Department of Psychology, Northern Illinois University, Dekalb, IL 60115, estevens@niu.edu