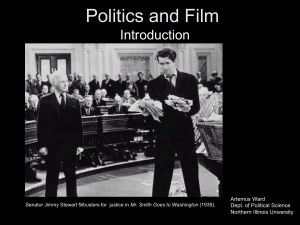

Introduction: Law, Politics, Film

advertisement

Law, Politics, and Film Introduction The Corleones: Michael, Don Vito, Sonny, and Fredo – an American family business. Artemus Ward Dept. of Political Science Northern Illinois University Hollywoodland’s Portrayal of the Law • Real World v. Reel World—There is a tension between actual legal practices in the “real world” and their portrayal in pictures. Cinematic practices and imperatives give rise to a “reel world” view of the law. • In this course introduction, we will discuss some basic cinematic practices. During the course we will discuss how these practices affect our impressions of law and politics. Cinematic Practices & Imperatives • It is a visual medium and therefore image is privileged over all other forms. • Film-making is a business. The goal is to make money and therefore films will tend toward the largest common denominator. • As a result, formulas and practices have developed over the years, such as the infamous “happy ending” and the use of music and special effects to induce audience reactions. Charlie Chaplin as “The Tramp.” In 1919 he founded United Artists with Actors Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks and filmmaker D.W. Griffith. Censorship • • • • In Mutual Film Corp. v. Ohio Industrial Commission (1915), the U.S. Supreme Court held 9-0 that films were not protected under the 1st Amendment’s freedom of speech and press clauses: “The exhibition of moving pictures is a business, pure and simple, originated and conducted for profit ... Johnny Weissmuller with a nude showgirl in not to be regarded, nor intended to be regarded… Glorifying the American Girl (1929). we think, as part of the press of the country, or as organs of public opinion.” As a result, state and local governments could practice prior restraint against films before their release. Under government and interest group pressure, the motion picture industry adopted the Hays Code (1930) to police itself. By 1935 or so, the industry’s Production Code Administration (PCA) began supervising every facet of a film and only issued it’s seal of approval if a picture was free of objectionable material. The Code proved economically beneficial to the Will H. Hays, Jr. was the chairman of the industry as films were no longer censored, the Republican National Committee and campaign code provided positive publicity, and “safe” films manager for Warren Harding’s successful 1920 such as the popular Shirley Temple pictures Presidential run. Harding named him Postmaster General. Hays later served as the first president cleaned up at the box office. of the Motion Picture industry (1922-1941). The Hays Code The Production Code enumerated three "General Principles": • • • No picture shall be produced that will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin. Correct standards of life, subject only to the requirements of drama and entertainment, shall be presented. Law, natural or human, shall not be ridiculed, nor shall sympathy be created for its violation. Specific restrictions were spelled out as "Particular Applications" of these principles: • • • • • • • • • • • • Nudity and suggestive dances were prohibited. The ridicule of religion was forbidden, and ministers of religion were not to be represented as comic characters or villains. The depiction of illegal drug use was forbidden, as well as the use of liquor, "when not required by the plot or for proper characterization." Methods of crime (e.g. safe-cracking, arson, smuggling) were not to be explicitly presented. References to "sex perversion" (such as homosexuality) and venereal disease were forbidden, as were depictions of childbirth. The language section banned various words and phrases that were considered to be offensive. Murder scenes had to be filmed in a way that would discourage imitations in real life, and brutal killings could not be shown in detail. "Revenge in modern times" was not to be justified. The sanctity of marriage and the home had to be upheld. "Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing." Adultery and illicit sex, although recognized as sometimes necessary to the plot, could not be explicit or justified and were not supposed to be presented as an attractive option. Portrayals of miscegenation were forbidden. "Scenes of Passion" were not to be introduced when not essential to the plot. "Excessive and lustful kissing" was to be avoided, along with any other treatment that might "stimulate the lower and baser element." The flag of the United States was to be treated respectfully, and the people and history of other nations were to be presented "fairly." "Vulgarity," defined as "low, disgusting, unpleasant, though not necessarily evil, subjects" must be treated within the "subject to the dictates of good taste." Capital punishment, "third-degree methods," cruelty to children and animals, prostitution and surgical operations were to be handled with similar sensitivity. Ratings Jack Valenti was an aide in the LBJ White House. He ran the MPAA from 1966-2004. • However, Hollywood soon faced increasing pressure from both television and foreign films. • The Court overturned the Mutual Films precedent in Burstyn v. Wilson (1952), thereby prohibiting state and local governments from banning films due to their content. • The Code was revamped and ultimately scrapped in favor of a rating system promoted by new industry head Jack Valenti. The system began in 1968 and has remained in effect, with slight modification, ever since. Film Structure • The story has to move forward. The structural formula is: -- The Set-up establishes the main character and dramatic situation. -- The Act I Plot Point features the main character’s primary story decision, in opposition to the antagonist. -- The Mid-Point is the moment when the main character is forced into the antagonist’s world, thereby redefining the story premise, this time by the antagonist. -- The Act II Plot Point is the lowest point in the story where the main character has been defeated by the antagonist and lost his motivation. -- The Ending is where the main character realizes a deeper understanding of his struggle, and summons up the courage to defeat the antagonist. Sequencing • The Structure is further fleshed out through sequencing: 1. The main character faces a strong moral dilemma in achieving a goal. 2. The antagonist poses opposition, both morally and to the goal. 3. The main character confronts the major complication, but proceeds into the story. 4. The story moves into a new world, and the main character makes an achievement. 5. The antagonist takes control of the story, sets the counter-plot in motion. 6. The main character moves forward, believing himself to be victorious, but finds the antagonist to be equal and opposing. 7. The main character restates the goal, with renewed conviction, but experiences his first setback. 8. The antagonist spins the counter-plot forward, and achieves momentum against the main character. 9. The protagonist experiences defeat at the hand of the antagonist, and loses his moral strength. 10. The protagonist loses the will to achieve his goal, but resuscitates his motivation and moral strength. 11. The protagonist restates his goal and summons up his moral courage. The antagonist restates his mission to destroy the protagonist, as well as his motivation and courage. 12. The protagonist and antagonist prepare for confrontation, but the protagonist experiences an epiphany of moral courage that gives him what it takes to defeat the antagonist. The story resolves with the protagonist understanding his life with renewed meaning and understanding. Montage • • • French for “putting together.” An editing style where the audience’s attention is drawn to the camera, editing, and filmmaker. This is in sharp contrast to the classical Hollywood continuity system where the camera, editors, and filmmaker never draw attention to themselves. Developed by 1920s Soviet filmmakers, particularly Sergei Eisenstein, to create symbolic meaning. For example: – Tonal montage: a shot/scene ends with a sleeping baby to induce an emotional response from the audience—in this case calmness and relaxation. – Intellectual montage: a shot/scene ends and the next one begins to get the audience to think—for example the transition from Mount Rushmore to a sleeping car of the train to the train entering a tunnel in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959) – spoiler alert! Do not watch the clip (right) if you have not yet watched this movie! • However, we often think of montage as a series of short shots edited into a sequence to condense narrative. It is usually used to advance the story as a whole (often to suggest the passage of time), rather than to create symbolic meaning as it does in Soviet montage theory. The “Push it to the Limit” montage in Scarface (1983) is a classic example as is the sports training montage South Park parody in the “Asspen” episode. Mise-en-scène • French for “setting the scene.” • In contrast to montage, mise-en-scène is a filmmaking style of conveying the mood and information of a scene primarily through a single shot with lighting, décor, lenses, depth, camera framing and movement, etc. • Rope (1948) is an extreme example (see above clip). After the first cut in the opening sequence, the rest of the film is one continuous shot! Auterism • • Auterism—or “author theory” is the idea that films should reflect the author’s (filmmaker’s) vision. There is often a tension between the filmmaker’s intent and the audience’s interpretation. For example, Francis Ford Coppola intended The Godfather to be a critical indictment of law and lawlessness in America with the mafia as his vehicle. Instead, critics and audiences totally missed this point and saw it as valorizing the mythic family and the self-made man. Indeed the mafia loved the film and it helped revive old mafia customs such as kissing the ring. A new generation of gangsters have adopted the film as a kind of blueprint or how-to guide in amassing power and empire-building in America. This is not unlike the modern KKK’s reaction to D.W. Griffiths’ critical The Birth of a Nation (1915) – a landmark film based on Thomas Dixon’s 1905 book “The Clansmen: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan.” The film played a major role in helping revive the Klan and provided a kind-of valorizing template for their 20th century anti-civil rights activities. For example, the first post-civil war Klan never burned crosses, but the book and film’s portrayal of the practice resulted in the practice’s adoption by the modern Klan. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor explained this in her majority opinion in the landmark cross-burning case Virginia v. Black (2003), where the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a state law criminalizing cross-burning on free speech/expression grounds. Snoop Dogg’s The Doggfather (1996). D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). Course Themes • Justice—We will ask how Hollywood portrays justice. Is justice a product for the formal legal system or can justice be served outside of formal rules and Salvatore Corsitto and Marlon Brando in The Godfather (1972). structures? • Fairness—Are all persons “equal under the law?” Are there class, race, sex, and other biases that make fairness impossible? Course Themes • Law Enforcement—In terms of resolving legal problems, how effective are public authorities and formal structures compared to private heroes? • Context/Setting—Location, location, location. Are legal problems resolved differently depending on the setting? Is urban law and justice different from rural law and justice? Is Los Angeles different from Chicago and New York? Course Themes Walter Matthau and Tatum O’Neil in The Bad News Bears (1976). • Divorce—We will look at the civil procedure and emotional/social issues portrayed in divorce films. While we will comment substantively about what these films teach us about how divorce affects both adults and children (as demonstrated by the above clip from The Bad News Bears), we will also be concerned with the role played by formal legal and institutional structures compared with more informal/non-legal entities. Course Themes • Women in the Law—We will also ask the proverbial question: “Are women the weaker sex?” • How are they portrayed in relation to the legal world? • When they are depicted as legal actors, how are they portrayed in relation to male legal actors? • Has their depiction changed over time? Tom Cruise and Demi Moore in A Few Good Men (1992). Conclusion Alfred Hitchcock on the set of Psycho (1960). • Movies reflect powerful narratives/myths (whether author or audience driven) that influence our reactions to issues we meet in real life, including legal issues. • Perhaps the “rule of law” is best viewed as one more narrative/myth competing for audience acceptance. • Indeed, what “law” is or what is “legal” has become an increasingly porous concept. Is law the province of specialists or is It a consciousness that permeates all of American culture. • We can think of motion pictures as legal “texts” in the same way that we think of constitutions or case-law books. Each can teach us something about a culture.