KrizCapstone

advertisement

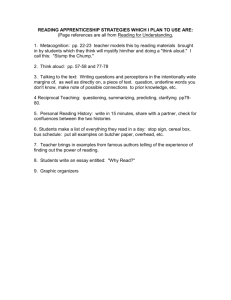

Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners Leah Kriz Vanderbilt University 1 Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 2 Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Book Selection………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Book Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Vocabulary Emphasis………………………………………………………………………………………………11 Strategy Instruction……………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 After Reading………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 23 Limits to Read Alouds …………………………………………………………………………………………… 24 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Future Research …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 27 References ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 29 Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 3 Abstract Teachers use read alouds in the classroom to promote learning and increase classroom discussion about text. In order for this instructional practice to benefit students, it should align with what students know and should include appropriate ways of expanding their knowledge. The teacher will need to tailor instruction accordingly for a classroom that includes students of diverse backgrounds. There are many factors involved in creating a successful read aloud, which include the book selection, the introduction activities, vocabulary emphasized during reading, specific strategies for understanding text, and the conclusion activities after reading. The book selection, vocabulary emphasized, and specific reading strategies are three aspects that will be greatly influenced when doing a read aloud in a diverse classroom. In selecting a book for a read aloud, the teacher should consider his/her learners and what content/strategies they need to learn. This is true for every classroom, but teachers must be cognizant of how the book will relate to and benefit specific students. Students come to school with many different levels of vocabulary knowledge and the teacher should realize this and be equipped to teach new vocabulary to them. A read aloud is an effective way to teach new vocabulary in context, but selection of words must be purposeful. During this type of instruction, a teacher can explicitly teach reading strategies through thinking aloud and involving students in the comprehension process. While doing this with diverse learners, it is important to acknowledge differences in background knowledge among students. Another important adaptation involves the type of questioning used while reading to accommodate or even take advantage of the differences in culture. Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 4 In this synthesis of information on components of the read aloud process and how they relate to diverse learners, there are clear conclusions about what this means and what needs to be done in order to benefit all students. Introduction Read alouds are a common teaching practice in many classrooms. If a teacher can implement them appropriately and effectively, students can learn a great deal about reading strategies, vocabulary, and comprehension. If, however, a teacher is not able to reach his/her students on a common level of understanding, the students will not benefit from this practice. This, therefore, means that teachers need to pay close attention to how they use read alouds in the classroom when working with students of cultures different than their own. It cannot be enough to simply read a book and expect students to automatically learn strategies, deeper meanings, and new vocabulary. It is the teacher’s role to ensure that all students can gain as much as possible from rich texts. Cultural differences that may include language, background knowledge, vocabulary knowledge, or customary practices can make a read aloud different in a diverse classroom. Reading aloud is a complex task when done with instructional intentions. A teacher should always have a reason for doing a read aloud, which could involve teaching specific vocabulary, reading strategies, or types of texts. One of the greatest benefits of reading aloud is that it “makes available rich content so that children can analyze texts and compare them” (Fountas and Pinnell, 1996). This is important because it allows children to experience authentic and rich text before they can access it themselves. Students need experience with meaningful text even when they are new to interacting with text in a school setting or new to the language that involves literature, what Beck and McKeown Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 5 (2001) refer to as “text talk”. When done effectively, reading aloud to students allows teachers to model how they think about text, which shows students how to do the same thing. The students of a culturally and/or linguistically diverse classroom need certain modifications to general content in order to benefit fully from instruction. For this reason I will examine the types of activities surrounding a read aloud that are most appropriate for these learners with a focus on students from preschool to third grade age. The learning context that I will discuss revolves around a group dynamic of student-teacher interaction. In this format, a teacher leads a read aloud, while encouraging and requiring student participation and engagement. As recommended by Routman (1994), a “whole group area” should be a defined space where the students and teacher can gather to read together (p. 426). The curriculum that I’ve focused on involves the read aloud features that I will outline. A read aloud should not be the only activity that a teacher uses to teach reading, but is an important one. It is an integral part of the curriculum because the teacher can use it to teach strategies, extend vocabulary and concept knowledge, and review these periodically. The teacher will be able to assess their knowledge because a read aloud teaches or reviews a skill or topic. This can be done through assessment during the read aloud, discussion or wrap up activities directly following the read aloud, or extension activities afterwards, such as literature circles. The following are what successful and meaningful read alouds look like and also what teachers need to do in regards to teaching students from different cultures. When done correctly, a read aloud can be an influential tool in introducing students to reading. There are five components necessary to using a read aloud in the classroom, namely, book Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 6 selection, introduction, vocabulary emphasized, strategy instruction, and after reading. There is research on each of these components; however, the greatest differences for reading aloud in a culturally diverse classroom involve the book selection, the vocabulary emphasis, and the strategy instruction. Book Selection When selecting a book for a read aloud, a teacher must consider what will appeal to his/her students. According to Fountas and Pinnell (1996), who lay out guided reading selection and introductions, a book should have themes, topics, or concepts that are familiar to students and should address these in a way that will allow for students to make connections. “If students do not read about their cultural groups’ contributions or see pictures of people that represent their cultural backgrounds, they will likely feel alienated, and this will hinder academic performance” (Gollnick & Chinn, 2006, as cited in Morgan, 2009, p. 3). Agosto (2007) goes on to explain that students who feel accepted and welcome in school will make greater gains and have greater motivation in school. This means that teachers need to read books that all students can relate to, at one time or another. “Text should be selected on the basis of enabling students to make connections to real-life experiences and to their background with challenging ideas and content” (Conrad et al, 2004, p. 188). An important criteria for selecting any book to read in the classroom is using “culturally sensitive” books, “teachers can select those that are recommended by researchers who specialize in multicultural children’s books” (Morgan, 2009, p. 6). Roberts et al. (2005) describes how stereotypical books are still produced today, offending groups such as Native Americans. Hall and Williams (2010) conducted a study using Caldecott books for read alouds in a culturally diverse classroom. Even in these award-winning Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 7 books, they detect stereotyping of characters and also note that the particular students in the study read about unfamiliar content, such as snow. These examples illustrate a caveat for teachers who are trying to select appropriate books in the classroom. Even if a book has just been published or has received national awards, there is still potential for the book to have an inappropriate topic or aspects for a certain classroom. Morgan (2008) suggests general guidelines for a teacher to use when selecting a book: “The book should present accurate facts about specific groups. The characters should reflect the full complexity of men and women’s roles. The social issues of a group need to be described authentically and honestly. The illustrations should show an accurate cultural setting” (p. 106-H). More specific guidelines, outlined by Yokota (1993), are “ richness of cultural details, authentic dialogue and relationships, in-depth treatment of cultural issues, and the inclusion of members of ‘minority’ groups for a purpose (p. 159-160). It is important to consider these different aspects when choosing appropriate books for the classroom. McNair (2010) cites a study done by Sims (1982), in which she analyzed 150 books containing African American characters published between 1965 and 1979. In doing this, she found that there were two categories that stood out: “melting pot” and “culturally conscious” books. In “melting pot” books, the characters do not possess any differences in culture compared to Whites besides skin color. The “culturally conscious” books, on the other hand, portray African Americans accurately. For English Language Learner (ELL) students specifically, Agosto (2007) points out that when they read or hear texts that have familiar content and cultural similarities, they are able to focus on learning the language. Another point she makes is that picture books Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 8 with language that ELL students will generally understand makes the best use out of teaching through reading. According to Naidoo (2005), informational books are highly effective for teaching ELL students. Teaching content and language simultaneously in a way that allows students to build upon prior knowledge of both is a useful teaching strategy (Reid, 2002, as cited in Naidoo, 2005). Moss (2003) touches on five benefits of reading nonfiction texts during read alouds that include giving students information about the world in other places or times, demonstrating examples of nonfiction text structure, lending to connections with fiction books, providing curricular content necessary, and motivating students through interesting topics (as cited in Naidoo, 2005). Another benefit of providing nonfiction text during read alouds is that it incorporates content with learning to read. This is especially helpful for ELL students because it gives them interactions with language that they would not otherwise experience. Also specific to students is deciding whether the text has some known vocabulary and an intriguing plot line. The important thing to consider in choosing books that meet these criteria is interest. Books still need to be intriguing and motivating while also being comprehensible to students. Students should be able to relate to characters, which can present the need for teachers to find books for all different cultures (Coatney, 2004). Other important technical factors to consider for selection involve length of text, illustration quality, and opportunity to use reading strategies. A type of book especially helpful to ELL students is one that is heavily based on illustrations that go along with text. This allows pictures to tell a lot of the content in the story which can lead to making connections between words and meaning. Books that are predictable or have familiar patterns are also Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 9 useful because they repeat language and allow students to remember it (Tsarykovska, 2005). An effective way to enhance learning, especially in a read aloud where there is such scaffolding of teacher support, is to choose books that are complex and may expand a student’s thoughts on a topic (Beck & McKeown, 2001). Morgan (2009) points out that students may feel more comfortable interacting with teachers who can facilitate differences that arise from multicultural literature. The texts selected for a read aloud in the classroom should promote discussion among students (Shedd & Duke, 2008, p. 3). This discussion will allow the students to voice opinions as well as learn from others in the classroom. While there are many factors to consider when choosing a book to read aloud, it will be different for every classroom because it should be tailored to each group of students. Book Introduction The introduction to a read aloud depends heavily on what type of book is being read and what supports the students need. When first introducing a text, the teacher should specify what type of book he/she will be reading to them. This will prepare them in regards to knowing the purpose of the read aloud—they will know if it is either a narrative book or an expository text. In order for this to mean anything to the students, the teacher needs to also explicitly state the difference between these two types and how to read them for meaning accordingly (Santoro, et. al., 2008). According to research conducted by McGee and Schickendanz (2007) involving repeated read alouds of sophisticated books for preschool and kindergarteners, the introduction should be brief. They show the cover picture and sometimes the back cover and explain what students should be thinking about during the reading. They do not recommend talking about the book parts (title page, concepts of Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 10 print, dedication page, etc.) because it could interfere with the students’ attention to the story line. They do not do a picture walk with the students during the first read, but rather allow the students to experience the book during the actual reading. According to Holdaway (as cited in Fountas & Pinnell, 1996, p. 136), “a book introduction is ‘a brief and lively discussion in which the teacher interests the children in the story and produces an appropriate set for reading it’ (1979, p. 142).” The introduction is adjusted according to how challenging the text may be for the specific students being read to and also how much background knowledge they have about the concepts. There are many aspects to capitalize on when doing an introduction for students. Fountas and Pinnell (1996) compiled a list of possibilities including relating to students’ background knowledge and connecting to what the students know and allowing students to bring personal experience to text. Clay (as cited in Fountas and Pinnell, 1996, p. 137) makes the point that when a teacher starts an introduction with this type of discussion about what students already know in relation to the new concepts/topics, the discussion should be an interaction between the students and teacher (1991, p. 267). Other parts of an introduction can involve the teacher explaining the important concepts and themes of the book, summarizing the general meaning so that students know what to look for, analyzing the illustrations, and talking about the characters (p. 137). By selecting appropriate books and providing comprehensive introductions, a teacher can draw students into the book. Both of these important prereading factors influence how students think about the book and how they come to understand it. Because read alouds consist of teacher modeling (Kimball-Lopez, 2003), it is important then to show students how to think about text before it is even presented to them. Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 11 Because an introduction should build upon prior knowledge and familiar concepts, it is important to use what students know to expand on that knowledge. While following a third grade teacher through a read aloud, Iddings, Risko, & Rampulla (2009) emphasized the process he took in reading to the students. He started with a picture walk and discussion of some of the vocabulary in the story. This allowed students to connect pictures to words and encouraged them to consider using this strategy to understand the book. This brings in one difference between a typical read aloud and one for culturally and/or linguistically diverse students, the teaching of common vocabulary. While both incorporate new words, for these students, some words need to be introduced even before the story begins in order to access the information. According to Calkins (2001), students who may not be familiar with content or vocabulary will “profit enormously from…book introductions geared toward rehearsing and talking about some of the words and concepts in a book” (p.168). This part of the read aloud, then, can be a crucial piece to build background knowledge before even beginning the story. Vocabulary Emphasis The actual read aloud process can look different depending on the teacher, the audience, and the text. There are, however, specific components that are necessary to incorporate during this process. Capitalizing on the vocabulary in a given text is an underlying basis for a read aloud. According to Biemiller (2001), explicitly stated definitions and explanations of vocabulary are necessary for students to acquire new language. In a read aloud, then, a teacher should purposefully select new words to explain to students. Picking a limited number of new words to define in a read aloud is necessary so that the teacher does not provide an overwhelming amount of information. These words Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 12 should be pre-selected and “critical to understanding the story and are likely to be encountered in other books or useful in nonbook contexts” (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2002 as cited in McGee and Schickendanz, 2007, p. 744). In the context of reading, the teacher should stop at these words and briefly explain them so that students understand the meaning of the text. In an outline of a read aloud, Santoro et al. (2008) includes defining vocabulary before reading, including it while reading, and “introducing, reviewing, and extending” it after reading (p. 403). This means that there are also opportunities for the teacher to make these new words clear and accessible for student learning. Another way to introduce words, while also finding out what students know, is to first ask about the word. This allows the students who know to demonstrate their knowledge while teaching others who may not have that word in their lexicon (Shedd & Duke, 2008). According to McGee and Schickendanz (2007), the teacher should use words, pictures, gestures, or voice tone and speed to explain vocabulary. In repeated readings, the explanations can become more explicit and useful in other contexts and can include examples of how the word is used. This instructional sequence can include brief definitions or examples while reading or can be more in depth explanations that students need to understand an overall concept (Kindle, 2010). Another example of explicit teaching is Roskos’ (2008) method of “Say-Tell-Do- Play” which consists of a teacher saying a new word, the students repeating it, the teacher giving a short definition, the students repeating it to a friend, the teacher stopping while reading to do the repeating once again, and then encouraging the students to use the word in other contexts (As cited in Kindle, 2010, p. 68). A major finding of Justice and colleagues’ (2005) study of vocabulary acquisition for at-risk Kindergarteners concerns the “elaboration” of vocabulary over repeated readings Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 13 rather than “mere exposure” (p. 26). This means, then, that in order to teach this new vocabulary, it is not effective to simply read the words, but instead specifically define them for students. Because reading aloud is such a teacher-directed activity, it is important to teach as much important vocabulary as possible. Especially for students who are not able to read, teaching new vocabulary is a way to increase their repertoire of words. Brabham (2002) also found that a teacher merely reading new words produced the smallest vocabulary gains for students, while performance reading and especially interactional reading produced the greatest gains. In Dickinson and Smith’s (1994) study involving preschool classroom read alouds, they also detected a “strong association between childinvolved analytic talk and vocabulary development” (p. 117). This means, then, that students should be involved in the learning of these new words rather than just recipients of new information. According to Jimenez, Garcia, and Pearson (1996), Latino/a students had to use many more strategies for understanding vocabulary in a text than their Caucasian student counterparts. This was a large part of their comprehension strategies because of the unfamiliarity with words. Knowing this, a teacher should make sure when reading aloud to English Language Learners that he/she not only explains vocabulary but also thinks through how the student could figure out what those words mean. This modeling can be beneficial for students who will need the skills to read independently. While some words are introduced at the start of the book, words should also be introduced and reiterated throughout the story. Using the repeated reading model outlined by McGee and Schickendanz (2007), vocabulary instruction is an important aspect. In emphasizing picture definitions and gestures to explain new words, the teacher can reach English Language Learner students. Another way to teach vocabulary during a read aloud Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 14 that allows the student practice with oral language is having students repeat new words (Swanson & Howerton, 2007) and possibly even repeating short definitions. When choosing a text, the teacher should keep in mind the limited amount of new vocabulary and should use works that will provide words applicable in other contexts as well (Swanson & Howerton, 2007). Interestingly, Boykin (1994) cites a study done by Albury (1991) in which the vocabulary knowledge of low income fourth and five grade African American and European American students is compared. This study found, by providing four different vocabularylearning situations, that African American children performed lowest when vocabulary was taught under individual conditions. They did, however, outperform the European American students on the communal learning conditions. This provides evidence for the fact that African American students achieve more when in a communal environment. Read alouds, then, are a way to promote this learning. In a longitudinal study of low-income students, Dickinson and Porche (2011) found that aspects of teacher-student interaction in preschool had lasting effects on students’ language and literacy development. Namely, “Analytic talk during book reading was related to Grade 4 vocabulary and had indirect effects mediated throughout Kindergarten vocabulary… Engagement in analytic discussions about books may have directly foster vocabulary learning” (p. 882). This study shows that even when students may not be equipped with vocabulary knowledge before entering school, preschool practices can promote vocabulary learning. This early education is apparently crucial for students who wouldn’t otherwise have as extensive vocabulary knowledge needed for later grades. An interesting finding that Dickinson and Porche (2011) discovered was that the analytic Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 15 discussion was not highly correlated with Kindergarten vocabulary. They accounted for this by explaining that part of the lasting effects of analytic talk was the students’ ability to learn new words while discussing a book. This finding leads to the fact that teaching vocabulary definitions alone, even while a teacher reads aloud, may not be effective. Students need ways to learn new words and develop their vocabularies, rather than simply learning many new words. Teachers can read aloud to students from both fiction and nonfiction books. When reading aloud the nonfiction, the goal is usually to teach the factual information in a way that students will understand and enable them to make connections. Hickman (2004) points out “the thematic selection of texts provides students with many opportunities to use and extend new vocabulary and comprehension skills, as well as gain more depth of content knowledge…” (p. 722). She goes on to explain that teachers should pick words to teach that will help students explain personal experiences and analyze text, these are the words that will benefit their learning. They should be able to use the vocabulary they’ve learned in different contexts and should be able to use it to talk about the text and connections they’ve made. According to Reese and Harris (1997), “Because informational texts contain more varied and technical vocabulary than narratives, conversations surrounding informational texts may facilitate vocabulary acquisition (as cited in Pentimonti et al., 2010, p. 658). This is a useful way to view the information books, especially when teaching new concepts along with reading strategies. Silverman and Crandell (2010) found, again, that students’ learning of vocabulary was positively correlated to teachers’ use of vocabulary instruction in a read aloud. They also found, however, that when teachers extended this vocabulary use to non-read aloud Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 16 activities, students made even greater gains in learning. This shows the importance of creating meaningful, useful learning of vocabulary that can be used in other contexts. This vocabulary that they teach should come from higher-level books, so that they promote learning for the students. Kahn and Stahl (2009) recommend after a review of literature that “teachers who want to increase the amount of vocabulary learning through context is to have [the teachers] encourage their students to read more text of a level sufficiently challenging or containing words that might be learned from context”(p. 135). A read aloud, then, is a way to present these challenging texts in a meaningful way to teach the vocabulary. Strategy Instruction Another part of the read aloud process is teaching reading strategies to students. In this review, I look at only a few of the multitude of strategies that teachers can use. According to Teale, Paciga, and Hoffman (2007), “During the primary grades, it is essential to teach children appropriate comprehension strategies and skills that enable them to understand texts that are more complex than those made of everyday words they already know and conversations they routinely hear” (p. 346). This is especially important for students of different cultures who need extension of language use. Kong and Pearson (2003) explain that students of different cultures, specifically linguistically different, should be provided with many opportunities to engage in literacy practices with appropriate scaffolding. Santoro et al (2008) discovered that emphasizing comprehension strategies and discussion of a text led to positive student performance. The idea of “text talk” (Beck & McKeown, 2001) can be combined with culturally responsive teaching in a way that extends the students’ understandings and discussions of text. When the students are Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 17 reading about familiar topics and have sufficient background knowledge about them, they are more willing and able to participate in the interaction required in a read aloud (Conrad et al., 2004). In McGee and Schickedanz’s (2007) model of repeated readings, they recommend modeling, inference-making, and predictions in the first reading and then providing less modeling with more scaffolding questions for second and third readings. By doing this, the students are exposed to subtle cues when the teacher thinks aloud and are able to transfer this type of thinking to themselves. While this is important and necessary for all read alouds, it can especially help students from different cultures. The teacher provides language about text that questions and hypothesizes ideas and also forms conclusions and answers to questions (Galda & Beach, 2001). Questioning, however, can be a difficult strategy to use with students from different cultures. Many times a teacher may ask a question to students that elicits no response. There are different reasons for this, such as an ambiguous questions, low-level questions that do not lend to a thoughtful response, or students not being used to asking or answering questions during learning (Mohr & Mohr, 2007). A model that Goldberg (1993) explores is “instructional conversation” (Tharp & Gallimore, 1988, 1989) which is based on the assumption that having rich discussion and meaningful use of language in learning will be beneficial to ELL students. In a read aloud, then, it is important for the teacher to model thinking and asking questions and also allow students to make input. A teacher should also understand that students, when presented with a question, may not know how to verbalize what they are thinking or want to convey (Jimenez, Garcia, & Pearson, 1996). Kindle (2010) found that teachers favor questioning over other strategies during a read aloud. This shows that Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 18 questioning is an important aspect of this instructional technique, but teachers should use them carefully. There can be different types of questions that teachers ask. According to Cazden (2001, as cited by Mohr & Mohr, 2007), there are differences between display questions and exploratory questions. Display questions involve lower level thinking demand for answers; these would include literal questions that have one right answer. Exploratory questions, on the other hand, lend themselves to thought-provoking answers and discussion where there is no one right answer. These can be more meaningful for students, but also take practice for them to become comfortable with. According to Jimenez, Garcia, and Pearson (1996), Latino/a students include questioning as a skill that they can transfer from one language to another. It is important for the students to see the connections between first language and second language. Throughout a reading, teachers ask questions concerning different strategies. These questions help to give more of the control to the students and allow them to think about what they’re reading. While modeling is important in helping students think about text, some questions can allow students to take initiative in thinking about it (Klesius and Griffith, 1996). Another way to incorporate questions can be using them in subsequent readings of the same text once the teacher has modeled his/her own thinking already. Questioning strategies can sometimes be the root of differences between the mainstream Western culture that is prevalent in the classroom and other cultures. For example, Tweed and Lehman (2002) point out the difference between East Asian and Western cultures in this regard. Western students are encouraged to question throughout the learning process, as seen during a typical read aloud, but East Asian students typically follow an ordered pattern of “memorizing, understanding, applying, and questioning or Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 19 modifying” (p. 96). For this reason, not all students will feel comfortable immediately questioning information they read about. Much like the previous example, Mohr and Mohr (2007) explain that immigrant students may come from these cultures that do not encourage asking or answering questions, but instead encourage listening quietly to the teacher. Another example of this difference is cited in Hart and Risley (1995), in which they find that higher socioeconomic status (SES) parents use more indirect requests with their children, while lower SES parents use more direct commands. While Hart and Risley (1995) discuss this in a negative way and link this to issues in school where lower SES students are not prepared for the culture of the classroom, Dudley-Marling and Lucas (2009) take a different stance. In their point-of-view, students with parents who use different questioning techniques have language differences, not deficiencies. In knowing this, a teacher using a read aloud in the classroom should pay close attention to his/her questioning techniques to ensure that all students are benefitting. Another strategy that teachers use during read alouds is making connections. In providing students with the opportunity to do this throughout the text, the teacher allows them to relate their present learning to something that they already know about. They can relate text to themselves through characters or events, to other books that they’ve heard or read, or to outside events that they recall (Hughes, 2007). By using schema, a reader can develop new understandings and ideas about what they know in order to form new conclusions (Anderson, 2004, as cited by Morrison & Wlodarczyk, 2009). When modeling how to make connections, the teacher should purposefully explain what he/she is doing in order to allow students to see when and where to make connections. Because this is based on such a personal level of background knowledge and recall, students should be Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 20 encouraged to think for themselves and make relevant connections in their own lives. This emphasizes the importance of the book selection, so that students have some prior knowledge in which they can build upon. When students enter school without knowledge of the language and culture, it can be difficult to assimilate. “Minority children could have a handicap if stories, texts, and test items presuppose a cultural perspective that the children do not share” (Anderson, 1994, p. 601). Anderson (1994) goes further to explain that lack of background knowledge about a particular topic could cause a child to have trouble with comprehension. All readers have an underlying expectation about what characters should act like, which is reflective of their own life experience (Galda & Beach, 2001). This means, then, that students from diverse backgrounds may have different understandings or predictions about text. A teacher needs to use this understanding in order to help his/her students reach mutual understanding of aspects of our culture and people that may be different than their own. Galda and Beach (2001) suggest that reading should open students to looking at the whole system in which characters are shaped and come to consider the differences between text and their own experience. “Research has revealed that students from culturally and linguistically diverse families possess a wealth of cultural knowledge and experiences that can be used to enhance their literary development” (Moll & Gonzalez, 1994, as cited in Manyak, 2008). A read aloud is a crucial time for a teacher to learn about these differences and allow students to share what they know and how they interpret text. According to Harper and Brand (2010), “Goals for incorporating multicultural literature into the early childhood curriculum include facilitating children’s understanding of and respect for their own and others’ cultural identities, assisting children to consider multiple perspectives and Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 21 experiences of others, and fostering children’s empathy” (p. 225). This means that all the students in the class can learn from each other through difference in perspective and cultural experiences. This can also be true for the dynamic between the teacher and students. As Kong and Pearson (2003) point out in their discussion of Book Clubs, which can also apply to read aloud topics, English language learners have different experiences that they can share with students. This allows for building upon background knowledge but also for exposing all students to broader ideas and cultural awareness. Another main conclusion in their research leads to the fact that ELL students need to have exposure and interaction with meaningful text and need to gradually move from a great deal of support to less support, as appropriate. This can be done even when the students do not have full mastery of the language. Beck and McKeown (2001) present a caveat to using background knowledge by pointing out that it is important to ensure students are using text to think about what will happen in the story. If children use primarily background knowledge without considering and developing new ideas involving the present text, it can be ineffective. As a teacher, this is important to keep in mind. When a teacher thinks aloud while reading a text, it can be used as “an instructional practice to help students verbalize the thoughts they use during reading, and thus bring that thinking into the open to that they can replicate it more effectively in the future” (Oster, 2001, as cited in Collins Block & Israel, 2004). This process not only allows children to see the teacher’s comprehension strategies, but can also give them vocabulary to use when they discuss the strategies. A read aloud is a time for interaction between the teacher and the students in the classroom. This interaction can foster communal development and Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 22 encouragement of others. According to Boykin (1994), African American students emphasize communalism and work well together rather than in a competitive way. While a lot of our current mainstream culture is competitive in nature, a teacher can reinforce this type of communal learning and interacting during the read aloud. This will not only allow more children in the classroom to benefit from their learning, but can also encourage this collaborative way of interacting in general. Williams et al (2002) points out that teachers should be “facilitators” of the discussion and allow students to make contributions and arrive at their own understandings of text” (pg. 235). Dickinson and Smith (1994) also found that this “teacher-student dialogue” is necessary for students to “engage fully in the [the most beneficial] type of analytic talk” (p. 118). In using books that contain multicultural topics or at least cultural topics other than our own, the teacher can emphasize critical literacy. “A critical literacy approach includes a focus on social justice and the role that each of us plays in challenging or helping to perpetuate the injustices we identify in our world” (Leland, Harste, & Smith, 2005, p. 259). This type of reading not only boosts comprehension, but also gives children a way to express their thoughts and feelings on a topic. There are many different ways to conduct read alouds in the classroom. Here I have focused on ones that would include discussion throughout the book in order to promote strategy use while reading. Dickinson and Smith (1994) found, however, that students made greater gains with “performance-oriented” reading rather than “didacticinteractional” reading. The “performance oriented” is described as “limited discussion…followed by extended discussion”, while the “didactic-interactional” is describes as responding to “factual details”. Regardless, the “child-involved analytic talk”, Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 23 either during or after a reading produced effects on story understanding. “Many conventionally trained teachers would see these different norms of interaction as signs of disruption or ill-discipline. Yet they relate directly to home and community values…” (Corson, 2001). These different considerations relate to teaching read alouds because they involve how to treat students from different backgrounds and how to incorporate them into the classroom environment. After Reading As part of a read aloud, the teacher should provide some type of concluding activity or explanation. This can show up in different forms based on how many readings of the same book have been done and what the learning goal of reading the book consisted of. In line with McGee and Schickedanz (2007), the three read alouds that they suggest should differ slightly in afterward discussion. At first, the teacher should lead more of the questions and they usually consist of straightforward questions about events in the book and characters’ actions. In repeated readings, more of the questions are based on hypothetical thinking and deeper understanding of the text. Another way to wrap up a story can be a retelling, either by the teacher, students, or a co-construction. Many times, a teacher will work with students to construct a retelling of events in order to ensure that students understood what happened in the story (Santoro et. al., 2008). In Iddings et al.’s (2009) account of the third grade teacher, it is evident that he works with the students throughout the read aloud to assist their language. He encourages students to answer questions and to ask questions and also clarifies and restates what the students say. This affirms their input and helps them to hear it being said again/correctly. One way that this teacher summarizes the story, which is beneficial to many students, but Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 24 English Language Learners especially, is making a chart of the story. This allows him to use a visual representation of events in the story so that students can hear him, look at the book, and look at the chart information. McGill-Franzen, Landford, and Adams (2002), in a study of five different preschool programs, found the most effective use of read alouds included discussion before, during and after reading. The discussion after reading can revolve around concepts that arise in the text and can also allow all students to make input. During this time, the teacher can informally assess the students’ understanding of the text based on the comments that they make. Another way to extend the learning and capture evidence of this is to link the read aloud to writing. “Read aloud and shared reading offer opportunities for children to respond orally to texts and familiarize them with the types of responses they’ll later be asked to write” (Taberski, 2000, p. 81). Kimball-Lopez (2003) suggests an extension activity of journal writing so that students can analyze text, ask questions, and/or make connections to the text. Another idea that Taberski (2000) presents involves story mapping for different elements of a story. This not only provides visual access to the text, but also gives students a demonstration for producing their own story maps. This is another assessment tool that the teacher could use to check for specific understanding. Limits to Read Alouds There has been research that disputes the effectiveness of read alouds, while I have only thus far provided why the teaching method is beneficial. This research focuses on problems with read alouds that are done poorly, which is why I am careful to point out that it must be done explicitly. Meyer and colleagues (1994) found through a longitudinal study that the amount of time spent reading aloud to Kindergarten students did not have a Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 25 positive correlation to reading achievement for these students (as cited in McGee & Schickedanz, 2007; Lane and Wright, 2007). They based this lack of correlation on ineffectiveness of the read alouds. According to the study, merely reading to students will not necessarily help them, but instead by doing so in a meaningful way. In reflection of this point, it is important to realize that a read aloud, when done like the supporting research suggests, will be effective. Another problem that McGee and Schickedanz (2007) point out involves the types of books that teachers choose to read, especially to at-risk students. In their research they find more cases of teachers reading predictable, low level books rather than higher level, sophisticated stories. This can be problematic in making the reading meaningful for students and therefore can also hinder progress. According to a review of empirical research, Scarborough and Dobrich (1994) found that parent-preschooler shared reading (parents reading aloud) led to only an 8% difference in reading ability. They point to factors such as Socio-economic Status (SES), child interest in reading, early ability among children, and parent influence on reading. These are understandable variables and do lead to differences in reading ability. This research, however, is also based off of home interactions, whereas the read alouds that I am considering are led by teachers in a classroom setting. Still another barrier to making a read aloud successful and beneficial to students involves lack of training and planning on a teacher’s part. According to Kindle (2010), in a study that followed teachers who had not received professional development in teaching vocabulary through read alouds, these teachers needed more guidance. She found that teachers’ word selection and use of context to explain vocabulary needed the most Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 26 improvement. For this reason, it is important to ensure that classroom teachers attend training and perform personal research on how to implement read alouds. Conclusion “Reading aloud is seen as the single most influential factor in young children’s success in learning to read. Additionally, reading aloud improves listening skills, builds vocabulary, aids reading comprehension, and has a positive impact on students’ attitudes toward reading” (Routman, 1994, p. 32). If this is true, teachers need to incorporate such a powerful tool into their teaching practices. Teachers need to know their individual students’ needs in order to promote growth and success for this to be possible. This should be done in such an environment that not only provides comfort in expressing ideas and learning new concepts, but also fosters a specific type of interactional learning between students and teachers. In doing this, a teacher will be able to assess the students based on what they’ve learned or reviewed in a communal environment. There is such a great deal of research on the effectiveness and benefits of read alouds in the classroom, which has convinced teachers tend to adopt the technique. However, many do not properly research the subject or receive instruction on the proper utilization. In order to make read alouds beneficial, teachers need to participate in professional development that deals with implementation. It is not enough to simply read books to students without providing these structural components of the read aloud format. All teachers in younger grades classrooms should be encouraged to participate in this development opportunity. Teachers of culturally and/or linguistically diverse classrooms, however, should be required to receive additional instruction properly addressing the diversity of their students. The read aloud is an important activity in the curriculum for Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 27 learning of specific contents as well as reading strategies, and all students should benefit accordingly. The only way that these students will benefit, however, is by having teachers who have an understanding of the accommodations necessary. When selecting books, the teacher needs to recognize multicultural literacy and use books appropriate to content, strategies, and cultural concerns. For the actual read aloud, the teacher must acknowledge where his/her students are in terms of content knowledge and background knowledge in order to determine how to introduce the book. Throughout the reading, he/she needs to realize the potential differences in understanding based on background knowledge of students. He/she also needs to ensure that types of strategies used throughout are culturally responsive in format of questioning and responses expected. Finally, after the book, the teacher should use activities to not only solidify learning among the students, but also as assessments to ensure they’ve understood the material. Future Research There is a great deal of research from both past and present about read alouds in the classroom. The cultural component of this instructional technique, however, is lacking. There should be more specific studies done on this topic so that teachers can have models on which to base their instruction. This could be a large area of interest, because the read alouds are so effective in the classroom for teaching content and strategies. In schools that are becoming more and more diverse, this read aloud adaptation is necessary. Without the research to back it up specifically, there won’t be school-wide improvement in this area. Another way to promote the use of culturally responsive read alouds is to design read aloud guidelines for teachers based on this research. In doing this, teachers would be Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 28 able to have a resource from which to find books that relate to specific content or strategies. Along with these book citations would be ways to introduce the text, ways to use different strategies effectively with students of diverse cultures, and then activities to wrap up the text in a meaningful way. While there can never be a prescribed method for this type of instructional opportunity because of the diversity of students, it would benefit teachers to not only received professional training, but also have guides and examples of effective read alouds and to use. Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 29 References Agosto, D. E. (2007) Building a multicultural school library: Issues and challenges. Teacher Librarian, 34(3), 27-31. Anderson, R.C. (1994). Role of the readers’ schema in comprehension, learning, and memory. In R.B. Ruddell, M.R. Ruddell, & H. Singer (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (4th ed., pp. 448–468). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Beck, I. L. & McKeown, M. G. (2001). Text talk: Capturing the benefits of read- aloud experiences for young children. The Reading Teacher, 55(1), 10-20. Biemiller, A. (2000). Teaching vocabulary. International Dyslexia Association Quarterly Newsletter, 26(4). Block, C. C., & Israel, S. E. (2004). The ABCs of performing highly effective think-alouds. Reading Teacher, 58(2), 154-167. Boykin, A. W. (1994). Afroculture expression and its implications for schooling. In Etta Hollins, Joyce King, and Warren Hayman (Eds.), Teaching diverse populations (pp. 243-257). Albany: State University of New York Press. Brabham, E. G. & Lynch-Brown, C. (2002). Effects of teachers’ reading-aloud styles on vocabulary acquisition and comprehension of students in the early elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 465-473. Calkins, L. M. (2001). The art of teaching reading. New York: Longman. Coatney, S. (2004). What about the collection? (Primary voices). Teacher Librarian, 32(2), 47. Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 30 Conrad, N.K., Gong, Y., Sipp, L., & Wright, L. (2004). Using text talk as a gateway to culturally responsive teaching. Early Childhood Education, 31(3), 187-192. Corson, D. (2001). Language Diversity and Education. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. Dickinson, D. K. & Smith, M. W. (1994). Long-term effects of preschool teachers’ book reading on low-income children’s vocabulary and story comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 29(2), 104-122. Dickinson, D. K. & Porche, M. V. (2011). Relation between language experiences in preschool classrooms and children’s kindergarten and fourth-grade language and reading ability. Child Development, 82(3), 870-886. Dudley-Marling, C., & Lucas, K. (2009). Pathologizing the language and culture of poor children. Language Arts, 86(5), 362-370. Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (1996). Guided reading. Good first teaching for all children. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Galda, L. & Beach, R. (2001). Response to literature as a cultural activity. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(1), 64-73. Goldenberg, C.N. (1993). Instructional conversations: Promoting comprehension through discussion. The Reading Teacher, 46, 316-326. Hall, K. W. & Williams, L. M. (2010). First-grade teachers reading aloud Caldecott awardwinning books to diverse 1st-graders in urban classrooms. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 24, 298-314. Harper, L. J. & Brand, S. T. (2010). More alike than different: Promoting respect through multicultural books and literacy strategies. Childhood Education, 86(4), 224-233. Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 31 Hughes, J. M. (2007). Teaching language and literacy, K-6. University of Ontario Institute for Technology, http://faculty.uoit.ca/hughes/Reading/ReadingProcess.html Hickman, P., Pollard-Durodola, S. & Vaughn, S. (2004). Storybook reading: Improving vocabulary and comprehension for English-language learners. The Reading Teacher, 57(8), 720- 730. Iddings, A. C. D., Risko, V. J., & Rampulla, M. P. (2009). When you don't speak their language: Guiding English-language learners through conversations about texts. Reading Teacher, 63(1), 52-61. Jiménez, R.T., García, G.E., & Pearson, P.D. (1996). The reading strategies of bilingual Latina/o students who are successful English readers: Opportunities and obstacles. Reading Research Quarterly, 31, 90-112. Justice, L. M., Meier, J. & Walpole, S. (2005). Learning new words from storybooks: An efficacy study with at-risk kindergarteners. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 36, 17-32. Kimbell-Lopez, K. (2003, February). Just think of the possibilities: Formats for reading instruction in the elementary classroom. Reading Online, 6(6). Retrieved from http://www.readingonline.org/articles/art_index.asp?HREF=kimbelllopez/index.html Kindle, K. J. (2010). Vocabulary development during read-alouds: Examining the instructional sequence. Literacy Teaching and Learning, 14(1&2), 65-88. Klesius, J. P. & Griffith, P. L. (1996). Interactive storybook reading for at-risk learners. The Reading Teacher, 49(7), p. 552-558. Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 32 Kong, A. & Pearson, P. D. (2003). The road to participation: The construction of a literacy practice in a learning community of linguistically diverse learners. Research in the Teaching of English, 38(1), p. 85-124. Kuhn, M. R. & Stahl, S. A. (2009). Teaching children to learn word meanings from context: A synthesis and some questions. Journal of Literacy Research, 30(1), 119-138. Lane, H. B. & Wright, T. L. (2007). Maximizing the effectiveness of reading aloud. The Reading Teacher, 60(7), 668-675. Leland, C. H., & Harste, J. C. (2005). Out of the box: Critical literacy in a first-grade classrooms. Language Arts, 82(4), 257-268. Manyak, P. (2008). Phonemes in use: Multiple activities for a critical process. Reading Teacher, 61(8), 659-662. McGee, L. M., & Schickedanz, J. A. (2007). Repeated interactive read-alouds in preschool and kindergarten. Reading Teacher, 60(8), 742-751. McGill-Franzen,A., Landford, C. &Adams, E. (2002). Learning to be literate: A comparison of five early childhood programs. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3),443- 464. McNair, J. C. (2010). Classic African American children’s literature. The Reading Teacher, 64(2), 96-105. Moher, K. A. J. & Mohr, E. S. (2007). Extending English-language learners’ classroom interactions using the Response Protocol. The Reading Teacher, 60(5), 440-450. Morgan, H. (2008). Teaching tolerance and reaching diverse students through the use of children’s books. Childhood Education, 85(2), 106G-106J. Morgan, H. (2009). Using read-alouds with culturally sensitive children’s books. Reading Improvement, 46(1), pp. 3- 8. Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 33 Morrison, V. & Wlodarczyk, L. (2009). Revisiting read-aloud: Instructional strategies that encourage students’ engagement with texts. The Reading Teacher, 63(2), 110-118. Moss , B. (2003). Exploring the literature of fact: Children’s nonfiction trade books in the elementary classroom. New York: Guildforld. Naidoo, J. C. (2005). Informational empowerment: Using informational books to connect the library medial center program with sheltered instruction. School Libraries Worldwide, 11(2), 132-152. Pentimonti, J. M., Zucker, T. A., Justice, L. M. & Kaderavek, J. N. (2010). Informational text use in classroom read-alouds. The Reading Teacher, 63(8), 656-665. Roberts, L., Dean, E. & Holland, M. (2005). Contemporary American Indian cultures in children’s picture books. Journal of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Retrieved September 28, 2011, from http://journal.naeyc.org/btj/200511/Roberts1105BTJ.pdf Routman, R. (1994). Invitations: Changing as teachers and learners K-12. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Santoro, L. E., Chard, D. J., Howard, L., & Baker, S. K. (2008). Making the very most of classroom read-alouds to promote comprehension and vocabulary. The Reading Teacher, 61(5), 396-408. Scarborough, H. S. & Dobrich, W. (1994). On the efficacy of reading to preschoolers. Developmental Review, 14, 245-302. Shedd, M. K. & Duke, N. K. (2008). The power of planning: Developing effective read-alouds. Journal of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Retrieved on Read Alouds for a Class of Diverse Learners 34 September 28, 2011, from http://www.naeyc.org/files/yc/file/200811/BTJReadingAloud.pdf Swanson, E. A. & Howerton, D. (2007). Influence vocabulary acquisition for English language learners. Intervention in School and Clinic, 42(5), 290-294. Taberski, S. (2000). On solid ground: Strategies for teaching reading K-3. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Teale, W., Paciga, K. A., & Hoffman, J. L. (2007). Beginning reading instruction in urban schools: The curriculum gap ensures a continuing achievement gap. Reading Teacher, 61(4), 344-348. Tsarykovska, O. (2005). Picture books and ESL students: Theoretical and practical implications for elementary school classroom teachers. In D. Henderson & J. May (Eds.), Exploring Cultural Diverse Literature for children and adolescents (108-117), Boston: Pearson. Tweed, R. G. & Lehman, D. R. (2002). Learning considered within a cultural context: Confucian and Socratic approaches. American Psychologist, 57(2), 89-99. Williams, J. P., Lauer, K. D., Hall, K.M et al. (2002). Teaching elementary school students to identify story themes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 235-248. Yokota, J. (1993). Issues in selecting multicultural children’s literature. Language Arts, 70(3),156- 167.