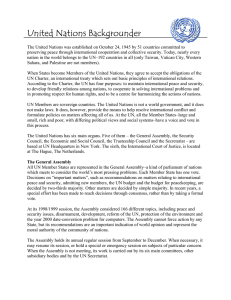

A General Assembly United Nations

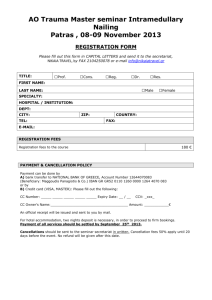

advertisement