ICC and Sherman Antitrust Act.doc

advertisement

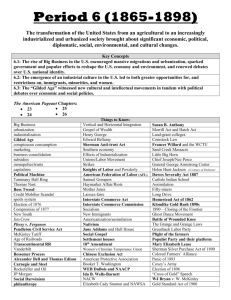

The Interstate Commerce Commission (or ICC) was a regulatory body created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland. The commission was designed to address the issues of alleged railroad abuse and discrimination and required the following: Shipping rates had to be "reasonable and just" Rates had to be published Secret rebates were outlawed Price discrimination against small markets was made illegal. The Commission's seven members were appointed by the President with the consent of the Senate. This was the first independent agency (or so-called Fourth Branch). The ICC's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later trucking) to ensure fair rates, to eliminate rate discrimination, and to regulate other aspects of common carriers. The ICC served as a model, or prototype, for later regulatory efforts. Unlike, for example, state medical boards (historically administered by the doctors themselves), the seven Interstate Commerce Commissioners and their staffs were full-time regulators who could have no economic ties to the industries they regulated. Post-1887 state and federal agencies adopted this structure. And, like the ICC, later agencies tended to be multi-headed independent commissions with staggered terms for the commissioners. At the federal level, agencies patterned after the ICC included the: * * * * * * Federal Trade Commission (1914) Federal Communications Commission (1933) U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (1933) National Labor Relations Board (1935) Civil Aeronautics Board (1940) Consumer Product Safety Commission (1975) The Sherman Antitrust Act, known as the Sherman Act, was the first United States federal government action to limit monopolies, and is the oldest of all U.S. antitrust laws. The Sherman Act provides: "Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal." The Act also provides: "Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a felony [. . . ]". The Act put responsibility upon government attorneys and district courts to pursue and investigate trusts, companies and organizations suspected of violating the Act. The Act was intended to prevent arrangements designed to, or which tend to, increase the cost of goods to the consumer. It was not specifically intended to prevent the dominance of an industry by a specific company, despite misconceptions to the contrary. According to Senator George Hoar, an author of the bill, any company which "got the whole business because nobody could do it as well as he could" would not be in violation of the act. The law attempts to prevent the artificial raising of prices by restriction of trade or supply. Some critics debate what the ultimate goal of antitrust legislation should be — increased competition or lower prices. For example, debating in favor of the Act in 1890, Rep. William Mason said "trusts have made products cheaper, have reduced prices; but if the price of oil, for instance, were reduced to one cent a barrel, it would not right the wrong done to people of this country by the trusts which have destroyed legitimate competition and driven honest men from legitimate business enterprise." In introducing federal "antitrust" legislation, Sen. Sherman and his congressional allies claimed that combinations or trusts tended to restrict output and thus drive up prices. If Sherman's claims were true, then there should be evidence that those industries allegedly being monopolized by the trusts had restricted output. By contrast, if the trust movement was part of the evolutionary process of competitive markets responding to technological change, one would expect an expansion of trade or output. In fact, there is no evidence that trusts in the 1880s were restricting output or artificially increasing prices. The Congressional Record of the 51st Congress provides a list of industries that were supposedly being monopolized by the trusts. Those industries for which data are available are salt, petroleum, zinc, steel, bituminous coal, steel rails, sugar, lead, liquor, twine, iron nuts and washers, jute, castor oil, cotton seed oil, leather, linseed oil, and matches. The available data are incomplete, but in all but two of the 17 industries, output increased-not only from 1880 to 1890, but also to the turn of the century. Matches and castor oil, the only exceptions to the general rule, hardly seem to be items that would cause a national furor, even if they were monopolized. As a general rule, output in these industries expanded more rapidly than GNP during the 10 years preceding the Sherman Act. In the nine industries for which nominal output data are available, output increased on average by 62 percent; nominal GNP increased by 16 percent over the same period. Several of the industries expanded output by more than 10 times the increase in nominal GNP. Among the more rapidly expanding industries were cottonseed oil (151 percent), leather goods (133 percent), cordage and twine (166 percent), and jute (57 percent). Real GNP increased by approximately 24 percent from 1880 to 1890. Meanwhile, the allegedly monopolized industries for which a measure of real output is available grew on average by 175 percent. The more rapidly expanding industries in real terms included steel (258 percent), zinc (156 percent), coal (153 percent), steel rails (142 percent), petroleum (79 percent), and sugar (75 percent). These trends continued from 1890 to 1900 as output expanded in every industry but one for which we have data. (Castor oil was the exception.) On average, the allegedly monopolized industries continued to expand faster than the rest of the economy. Those industries for which nominal data are available expanded output by 99 percent, while nominal GNP increased by 43 percent. The industries for which we have data increased real output by 76 percent compared with a 46 percent increase in real GNP from 1890 to 1900. As with measures of output, not all of the relevant price data are available, but the information that is at hand indicates that falling prices accompanied the rapid expansion of output in the "monopolized" industries. In addition, although the consumer price index fell by 7 percent from 1880 to 1890, prices in many of the suspect industries were falling even faster. The average price of steel rails, for example, fell by 53 percent from $68 per ton in 1880 to $32 per ton in 1890. The price of refined sugar fell from 9 cents per pound in 1880, to 7 cents in 1890, to 4.5 cents in 1900. The price of lead dropped 12 percent, from $5.04 per pound in 1880 to $4.41 in 1890. The price of zinc declined by 20 percent, from $5.51 to $4.40 per pound from 1880 to 1890.