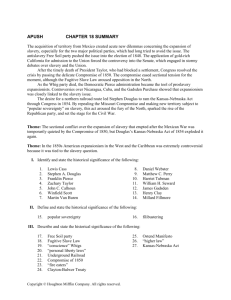

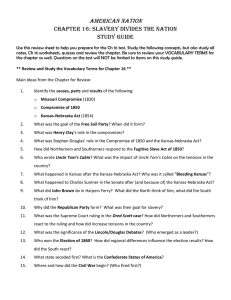

Kansas-Nebraska Act

advertisement

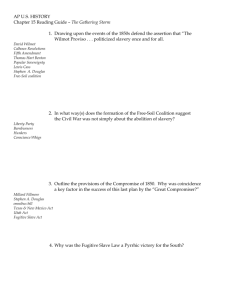

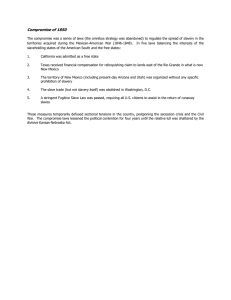

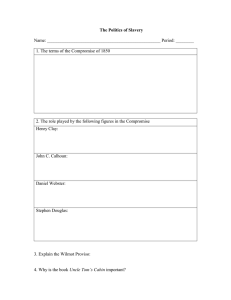

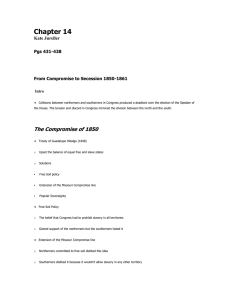

Kansas-Nebraska Act In January, 1854, Senator Stephen Douglas proposed a bill to organize the territory west of Missouri. The price of southern support, Douglas soon discovered, was the addition of an amendment explicity repealing the Missouri Compromise. He reluctantly agreed, and in this more controversial form, the bill made its way through Congress. It passed in the Senate by a large margin and passed narrowly in the House. Douglas’s bill split his party rather than uniting it. A group of independent Democrats denounced the bill as a “gross violation of a sacred pledge.” For many northerners, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was an abomination, striking them like a slap in the face because it permitted the possibility of slavery where it had previously been prohibited. Douglas’s bill had a catastrophic effect on sectional harmony. It repudiated a compromise that many in the north regarded as binding. In defiance of the whole compromise tradition, it made a concession to the South on the issue of slavery extension without providing an equivalent concession to the North. It also shattered the fragile sectional accommodation of 1850 and made future compromises less likely. The act also destroyed what was left of the two parties, the Whigs and the Democrats. The Whig party disintegrated when its congressional representation split cleanly along sectional lines. The Democratic Party survived, but its ability to act as a unifying national force was seriously impaired. They lost influence in the North and became the regional proslavery party of the South.