Class Lecture Notes 25.doc

advertisement

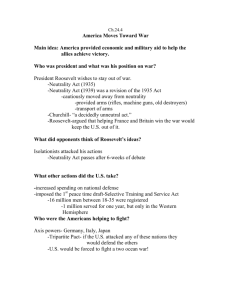

The American Promise – Lecture Notes Chapter 25 – The United States and the Second World War, 1939 - 1945 I. Peacetime Dilemmas A. Roosevelt and Reluctant Isolation 1. Seeking a Balance between Domestic and International Priorities— Franklin Roosevelt agreed with most Americans that the nation’s highest priority was to attack the domestic causes and consequences of the depression, but he had long advocated an active role for the United States in international affairs; depression had forced Roosevelt to retreat from internationalism, as he believed involvement in foreign affairs diverted resources and political support from domestic recovery. 2. The Soviet Union—Roosevelt established formal diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1933. 3. Germany and Japan—When the League of Nations condemned Japanese and German aggression, Roosevelt did not support the League’s attempts to keep the peace because he feared jeopardizing isolationists’ support for New Deal measures; he looked the other way when Hitler began to arm Germany. B. The Good Neighbor Policy 1. Latin America—In his 1933 inaugural address, Roosevelt announced that the United States would pursue “the policy of the good neighbor” in international relations, reversing the old policy of intervention in Latin America; commitment to military nonintervention did not indicate a U.S. retreat from empire in Latin America; instead, it declared the United States would not depend on military force in the region; honored the principle of self-determination, but it also permitted the rise of brutal dictators like Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua and Fulgencio Batista in Cuba, with private support from U.S. businesses. 2. Flexing Economic Muscles—Military nonintervention did not prevent the United States from exerting its economic influence; reciprocal tariff reductions doubled exports to Latin America; the nonintervention policy planted seeds of friendship and hemispheric solidarity. 1 of 11 The American Promise – Lecture Notes C. The Price of Noninvolvement 1. Fascism in Europe, Militarism in Japan—Fascist governments in Italy and Germany threatened military aggression; Hitler plotted to avenge defeat in World War I by recapturing territories with German inhabitants, all while accusing Jews of polluting the master race; in Japan, a stridently militaristic government planned to follow the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 with conquests extending throughout Southeast Asia. 2. American Neutrality—In the United States, hostilities in Asia and Europe only further reinforced isolationist sentiments; these hostilities and the Nye committee report, which concluded that greedy “merchants of death” had dragged the United States into World War I, prompted Congress to pass a series of neutrality acts between 1935 and 1937. 3. Cash-and-Carry Policy—Some Americans wanted a total embargo on trade with all warring countries, but Roosevelt and Congress worried that would hurt the economy; the Neutrality Act of 1937 established the “cash-andcarry” policy, which sought to allow trade but prevent foreign entanglements by requiring warring nations to pay cash for nonmilitary goods and transport them in their own ships. 4. Undermining Peace—Cash and carry helped the economy, but also undermined peace; this desire for peace in France, Britain, and the United States led Germany, Italy, and Japan to launch offensives on the assumption that the Western democracies lacked the will to oppose them; Hitler marched on the Rhineland; Italy conquered Ethiopia; Japan instigated the deadly Rape of Nanking. 5. The Spanish Civil War—In Spain, a bitter civil war broke out in 1936 when fascist rebels led by General Francisco Franco and supported by Germany and Italy attacked the democratically elected Republican government; with no opposition from the West, fascism triumphed. 6. Moderating Isolationism—Hostilities in Europe and Asia alarmed Roosevelt and other Americans; Roosevelt sought to persuade Americans to moderate their isolationism and tried to find a way to support the victims of fascist aggression; proposed that the United States “quarantine” aggressor nations; ignited a storm of protests from isolationists; strength of isolationist sentiment convinced Roosevelt that he needed to maneuver carefully if the United States were to help prevent fascist aggressors from conquering Europe and Asia and leaving America an isolated and imperiled island of democracy. 2 of 11 The American Promise – Lecture Notes II. The Onset of War A. Nazi Aggression and War in Europe 1. Austrian Anschluss—Under the spell of isolationism, Americans passively watched Hitler’s relentless campaign to dominate Europe; in 1838, he bullied Austria into accepting incorporation with the Nazi Third Reich. 2. Appeasement—British prime minister Neville Chamberlain went to Munich in September 1938 and offered Hitler terms of appeasement, giving the Sudetenland to Germany if Hitler agreed to leave the rest of Czechoslovakia alone; Hitler agreed, but he never intended to honor his promise; in March 1939, he marched the German army into Czechoslovakia and conquered it without firing a shot. 3. The Nazi-Soviet Alliance—In April 1939, Hitler demanded that Poland return the German territory it had been awarded after World War I; Britain and France assured Poland they would go to war with Germany if Hitler invaded the country; but Hitler negotiated with his enemy, the Soviet premier Joseph Stalin, offering concessions in exchange for Stalin’s promise that he would refrain from joining Britain and France in opposing Germany’s invasion of Poland. 4. Blitzkrieg—At dawn on September 1, 1939, Hitler unleashed the blitzkrieg on Poland; after the Nazis overran Poland, Hitler paused for a few months before launching a westward blitzkrieg that smashed through Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and France. 5. French Surrender—By mid-June 1940, France had surrendered the largest army in the world, signed an armistice that gave Germany control of the entire French coastline and nearly two-thirds of the countryside, and installed a collaborationist government at Vichy in southern France headed by Philippe Pétain. 6. The Battle of Britain—The new British prime minister, Winston Churchill, vowed that Britain, unlike France, would never surrender to Hitler; held off Germany at the Battle of Britain; but Churchill knew he needed American help. B. From Neutrality to the Arsenal of Democracy 1. Revising Neutrality—When the Nazi attack on Poland ignited the war in Europe, Roosevelt issued an official proclamation of American neutrality; but he feared Britain would soon succumb to the Nazi onslaught; after heated debate, Congress voted in November 1939 to revise the neutrality legislation and allow belligerent nations to buy arms, as well as nonmilitary supplies, on a cash-andcarry basis. 3 of 11 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 2. Assisting Britain—Churchill pleaded for American destroyers, aircraft, and munitions, but Britain lacked the funds to buy them; Roosevelt arranged to swap fifty old destroyers for American access to British bases in the Western Hemisphere. 3. Lend-Lease—In 1940, while Luftwaffe pilots bombed Britain, Roosevelt decided to run for an unprecedented third term as president; empowered by voters after being elected president for another term, Roosevelt maneuvered to support Britain in every way short of entering the war; in January 1941, Roosevelt proposed the Lend-Lease Act, which allowed the British to obtain arms from the United States without paying cash, instead promising to reimburse the United States when the war ended. 4. Hitler Attacks the Soviets—Stymied in his plans for an invasion of England, Hitler turned his massive army eastward, launching a surprise attack on the Soviet Union. 5. The Atlantic Charter—As Hitler’s Wehrmacht raced across the Russian plains and Nazi U-boats tried to choke off supplies to Britain and the Soviet Union, Roosevelt met with Churchill and signed the Atlantic Charter, which called for, among other things, freedom of the seas and the right of national selfdetermination. C. Japan Attacks America 1. Japanese Ambitions—Hitler exercised a measure of restraint in directly provoking America; unlike the Germans, Japanese ambitions in Asia, especially in China and the Philippines, clashed more openly with American interests and commitments; Japan planned to attack the United States if necessary. 2. The Tripartite Pact—In 1940, Japan signaled a new phase of its imperial designs by entering into a defensive alliance with Germany and Italy—the Tripartite Pact. 3. The Trade Embargo—When the United States discovered that Japan planned to invade the resource-rich Dutch East Indies, it announced a trade embargo that denied Japan access to oil, scrap iron, and other goods essential for its war machines; in October 1941, reacting to the American embargo, Japanese militarists, led by General Hideki Tojo, seized control of the government and persuaded Emperor Hirohito that the swift destruction of American naval bases in the Pacific would leave Japan free to follow its destiny. 4. Pearl Harbor—On December 7, 1941, Japanese planes attacked the American fleet at Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu and sank or disabled 4 of 11 The American Promise – Lecture Notes eighteen ships, killing more than 2,400 Americans; the Japanese scored a stunning tactical success at Pearl Harbor, but in the long run, the attack proved a colossal blunder; made the Japanese overconfident; united Americans in their desire to fight and avenge the attack. III. Mobilizing for War A. Home-Front Security 1. Reducing the Threat in the Atlantic—Shortly after declaring war against the United States, Hitler dispatched German submarines to hunt for American ships along the Atlantic coast from Maine to Florida; by mid-1942, the U.S. Navy had chased German submarines away from the East Coast, into the mid-Atlantic, reducing the direct threat to the nation’s homeland. 2. Internment Camps—The government worried constantly about espionage and internal subversion; campaign for patriotic vigilance focused on German and Japanese foes, but Americans of Japanese descent became targets of official and popular persecution; on February 19, 1942, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized sending all Americans of Japanese descent to makeshift internment camps, euphemistically called “relocation centers,” located in remote areas of the West; the Supreme Court, in its 1944 Korematsu decision, upheld the order’s blatant violation of constitutional rights as justified by “military necessity.” B. Building a Citizen Army 1. Selective Service—In 1940, Roosevelt encouraged Congress to pass the Selective Service Act to register men of military age, who would then be subject to draft into the armed forces if the need arose; all in all, more than 16 million men and women served in uniform during the war, two-thirds of them draftees, mostly young men. 2. Prohibiting Discrimination—The Selective Service Act prohibited discrimination “on account of race or color,” and almost a million African American men and women donned uniforms, as did half a million Mexican Americans, 25,000 Native Americans, and 13,000 Chinese Americans; black Americans were segregated, and most were consigned to manual labor; homosexuals also served in the armed forces, and, like other minorities, they sought to demonstrate their worth under fire. C. Conversion to a War Economy 1. More Jobs than Workers—In 1940, the American economy remained mired in the depression; nearly one worker in seven was still without a job; after 5 of 11 The American Promise – Lecture Notes Pearl Harbor, factories were converted from producing consumer goods to war materiel, and production was ramped up to record levels; by the end of the war, jobs exceeded workers 2. The War Production Board—To organize and oversee this tidal wave of military production, Roosevelt called upon business leaders to head new government agencies such as the War Production Board, which, among other things, set production priorities and pushed for maximum output. 3. Union Membership—Booming wartime employment swelled union membership; to speed production, the government asked unions to pledge not to strike; for the most part, unions kept their no-strike pledge. 4. The Arsenal of Democracy—Overall, conversion to war production achieved Roosevelt’s goal of “overwhelming, crushing superiority” in military goods; the United States produced more than double the combined production of Germany, Japan, and Italy. IV. Fighting Back A. Turning the Tide in the Pacific 1. Japan’s South Pacific Offensive—In the Pacific theater, Japan’s leading military strategist, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, ordered an all-out offensive throughout the southern Pacific; the Japanese unleashed a withering assault against the Philippines in January 1942 and by May 1942, Japanese forces had defeated the American and Philippine defenders; by the summer of 1942, the Japanese war machine had swooped from its Philippine successes to conquer the oil-rich Dutch East Indies and was poised to strike Australia and New Zealand. 2. A Two-Pronged U.S. Counteroffensive—U.S. forces launched a two-pronged counteroffensive that military officials hoped would halt the Japanese advance; first General Douglas MacArthur moved north from Australia and eventually attacked the Japanese in the Philippines; more decisively, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz sailed from Hawaii to retake islands in the South Pacific. 3. The Battle of Midway—Acting on intelligence, Nimitz maneuvered into the Central Pacific to surprise the Japanese; victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942 reversed the balance of naval power in the Pacific in favor of the United States and put the Japanese at a disadvantage for the rest of the war. B. The Campaign in Europe 1. The Eastern Front and the War in the Atlantic—After Pearl Harbor, Hitler’s eastern-front armies marched deeper into the Soviet Union while his 6 of 11 The American Promise – Lecture Notes western forces prepared to invade Britain; the war in the Atlantic remained undecided, but the introduction of radar detectors and sufficient numbers of destroyers escorts eventually drove the Nazi U-boats from the North Atlantic in late May 1943. 2. Delaying the Second Front—The most important strategic question confronting the United States and its allies was when and where to open a second front against the Nazis; Stalin demanded that America and Britain mount a massive assault into western France to relieve pressure on the Soviet Union; Roosevelt and Churchill delayed opening a second front, allowing the Germans and Soviets to slug it out. 3. North Africa—Churchill and Roosevelt decided instead to open the second front in North Africa; by May of 1943, the Allied armies defeated the Germans in North Africa, made the Mediterranean safe for Allied shipping, and opened the door for an Allied invasion of Italy. 4. Ruling Out Peace Negotiations—In January 1943, while the North African campaign was still underway, Roosevelt and Churchill met in Casablanca and announced that they would accept nothing less than the “unconditional surrender” of the Axis powers; ruled out peace negotiations; they also concluded that they were not yet prepared for the invasion of France, leaving Stalin to bear the brunt of the Nazi war machine for another year. 5. Invading Italy—On July 10, 1943, combined American and British amphibious forces landed 160,000 troops in Sicily; Italian government surrendered unconditionally, but German troops dug into strong fortifications and fought to defend Italy for the remainder of the war; Stalin denounced the Allies’ Italian campaign because it left the Soviet Army “to do the job alone, almost single-handed.” V. The Wartime Home Front A. Women and Families, Guns and Butter 1. Women at Work—Millions of American women gladly left home to take their places on assembly lines in defense industries; wartime mobilization and the siphoning of men into the armed forced left factories begging for women workers. 2. The “Victory Line”—Government advertisements urged women to take industrial jobs by assuring them that their household chores had prepared them for work on the “Victory Line”; advertisements often referred to a woman who worked in the war as “Rosie the Riveter.” 7 of 11 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 3. Married Women Support the War from Home—The majority of married women remained at home, occupied with domestic chores and child care; but they, too, contributed to the war effort by planting Victory Gardens, collecting tin cans and newspapers for recycling into war materials, and buying war bonds; war also influenced how families spent their earnings. 4. American Wartime Abundance—The wartime prosperity and abundance enjoyed by most Americans contrasted with the experiences of their allies; consumption fell by 22 percent in Britain; the Soviet Union witness widespread hunger and even starvation. B. The Double V Campaign 1. Victory at Home and Abroad—Fighting against Nazi Germany and its ideology of Aryan racial supremacy forced Americans to examine racial prejudice in their own society; Pittsburgh Courier called for a Double V campaign, victory over white supremacy at home and over fascism abroad. 2. Integrating Defense Work—In 1941, black organizations demanded that the federal government require companies receiving defense contracts to integrate their workforces; A. Philip Randolph promised that 100,000 blacks would march on Washington if the president did not eliminate discrimination in defense industries; responding to this pressure, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, which authorized a Committee on Fair Employment Practices to investigate and prevent racial discrimination in employment. 3. Unequal Job Opportunities and Wages—Progress came slowly; although black unemployment had dropped by 80 percent during the war, by the war’s end, the average income of a black family still stood at half of that of a white family. 4. Racial Violence—Blacks’ migration to defense jobs intensified racial tensions, which boiled over in the summer of 1943 when 242 race riots erupted in 47 cities; included the “zoot suit riots” in Los Angeles, where whites targeted Mexicans. 5. Civil Rights Organizations—The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), founded in 1942, organized picketing and sit-ins against Jim Crow restaurants and theaters; although membership in the NAACP greatly expanded, they achieved only limited success against racial discrimination during the war. C. Wartime Politics and the 1944 Election 1. Conservative Coalition’s Gains—Despite an overwhelming consensus on war aims, the stresses of the nation’s wartime mobilization made it difficult for Roosevelt to maintain his political coalition; Republicans took the opportunity to 8 of 11 The American Promise – Lecture Notes roll back New Deal reforms and abolished several agencies, including the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps. 2. The GI Bill of Rights—In June 1944, Congress unanimously approved the landmark GI Bill of Rights, which promised veterans government money for education, housing, and health care and made available low-interest loans so they could start businesses and buy homes. 3. Harry Truman—Roosevelt, exhausted and gravely ill with heart disease, was determined to remain president until the war ended; made choice of vice presidential candidate unusually important; convinced that many Americans had soured on liberal reform, Roosevelt chose Harry S. Truman, a reliable party man from a southern border state. 4. The Democratic Victory—Republicans, confident of a strong conservative upsurge in the nation, nominated as their presidential candidate the governor of New York, Thomas E. Dewey, who had made his reputation as a tough crime fighter; Roosevelt’s failing health alarmed many observers, but the majority of voters were unwilling to change presidents in the midst of the war and dismissed Dewey’s charge that the New Deal was a creeping socialist menace; Roosevelt won a 53.5 percent majority, his narrowest presidential victory. D. Reaction to the Holocaust 1. Jews Seek Asylum—After 1938, thousands of Austrian Jews sought to immigrate to the United States, but 82 percent of Americans opposed admitting them, and they were turned away. 2. Reports of the Holocaust—In 1942, numerous reports filtered out of Germanoccupied Europe that Hitler was implementing a “final solution”: Jews and other “undesirables”—such as Gypsies, religious and political dissenters, and homosexuals—were being sent to concentration camps. 3. Appeals to the Allies Go Unanswered—Most Americans, including top officials, believed the reports of the camps were exaggerated; only 152,000 of Europe’s millions of Jews managed to gain refuge in the United States before its entry into the war; the World Jewish Congress appealed to the Allies to bomb the death camps and the railroad tracks leading to them; Allied officials repeatedly turned down such requests, arguing that they could not spare the resources from the military missions. 4. The Allies Arrive at Auschwitz—When Russian troops arrived at Auschwitz in Poland in February 1945, the truth about the Nazi Holocaust was revealed; by the end of the war, Nazi troops had slaughtered 11 million civilian victims—mostly Jews. 9 of 11 The American Promise – Lecture Notes VI. Toward Unconditional Surrender A. From Bombing Raids to Berlin 1. Allied Bombing Missions—While the Allied campaigns in North Africa and Italy were underway, British and American pilots flew bombing missions from England to the continent as an airborne substitute for the delayed second front on the ground; German air defenses took a toll on Allied pilots, and two-thirds did not survive to complete their mission; the arrival in February 1944 of the P-51 Mustang fighter gave Allied bomber pilots superior protection. 2. Overlord—In November 1943, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin met in Teheran, Iran, to plan the Allies’ next step; Roosevelt and Churchill promised that they would at last launch a massive second-front assault in northern France; code-named Overlord, the offensive was scheduled to begin in May 1944. 3. D Day—German forces, commanded by General Erwin Rommel, fortified the cliffs and mined the beaches of northwestern France; but Germany had too many troops in the east trying to halt the Red Army’s westward offensive, and the Luftwaffe had been decimated by Allied air raids; on June 6, 1944—D Day—General Dwight Eisenhower launched the largest amphibious assault in world history; within a week, Allied soldiers, tanks, and other military equipment were sweeping east toward Germany. 4. The Yalta Conference—In February 1945, while Allied armies relentlessly pushed German forces backward, Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt met secretly at the Yalta Conference to discuss plans for the postwar world; Roosevelt secured Stalin’s promise to permit votes of self-determination by people in eastern European countries occupied by the Red Army. 5. The United Nations—The “Big Three” agreed on the creation of a new international peacekeeping organization, the United Nations (UN). 6. Victory in Europe—While Allied armies sped toward Berlin, Allied war planes dropped more bombs after D Day than in all previous European bombing raids combined; in April, the Soviets smashed into Berlin; Hitler committed suicide on April 30, and on May 7, a provisional German government surrendered unconditionally. 7. A New President—Roosevelt did not live to see the end of the war, and Americans worried about Harry Truman, his successor. 10 of 11 The American Promise – Lecture Notes B. The Defeat of Japan 1. Island Hopping—In the Pacific, Americans and their allies attacked Japanese strongholds by sea, air, and land, moving island by island toward the Japanese homeland. 2. Securing the South Pacific—In mid-1943, American, Australian, and New Zealand forces launched offensives in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, gradually securing the South Pacific; Japanese soldiers were ordered to refuse to surrender no matter how hopeless their plight. 3. Invading the Philippines—While the island-hopping campaign kept pressure on Japanese forces, the Allies invaded the Philippines in the fall of 1944; Allies won there, and the American forces captured the crucial islands of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. 4. The Failure of Kamikaze—Japanese leaders ordered thousands of suicide pilots to defend Okinawa, but they only demolished the last vestige of the Japanese air force; by June 1945, the Japanese were nearly defenseless on sea and in the air but their leaders prepared to fight to the death for their homeland. C. Atomic Warfare 1. The Manhattan Project—In mid-July 1945, as Allied forces were preparing for the final assault on Japan, American scientists tested the atomic bomb near Los Alamos, New Mexico; called the Manhattan Project; sent a mushroom cloud of debris eight miles into the atmosphere. 2. Truman’s Decision to Drop the Bomb—President Truman heard about the successful bomb test at Los Alamos when he was in Potsdam, Germany, negotiating with Stalin about postwar issues; he recognized that the bomb gave the United States an atomic monopoly that could be used to counter Soviet ambitions and advance American interests in the postwar world; also saw no reason not to use the atomic bomb against Japan if it would save American lives. 3. Japanese Surrender—When Japan refused to surrender unconditionally by the deadline, Truman ordered that the bomb be dropped without warning on Japanese cities not already heavily damaged by American raids; dropped the first bomb in Hiroshima on August 6; incinerated 100,000 people in Hiroshima and nearly as many in Nagasaki when the second bomb was dropped on August 9; Japan surrendered on August 14. 11 of 11