Class Lecture Notes 8.doc

advertisement

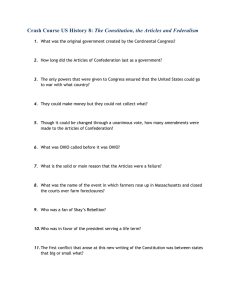

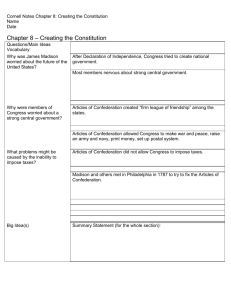

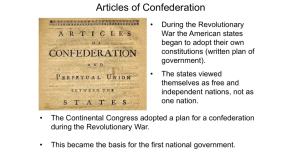

The American Promise – Lecture Notes Chapter 8 - Building a Republic, 1775 – 1789 I. The Articles of Confederation (Slide 2) Page 209 A. Congress and Confederation 1. Forming a Government—The Continental Congress wanted to draft a document that would specify what powers the congress had and by what authority it existed; delegates agreed a government should pursue war and peace, conduct foreign relations, regulate trade, and run a postal service; the congress reached agreement on the Articles of Confederation in November 1777; defined the union as a loose confederation of states with no national executive and no judiciary; congressional offices had a three-year term limit; routine decisions in the congress required a simple majority of seven states; declaring war required nine; approving or amending the articles required unanimous consent of thirteen state delegations and thirteen state legislatures; unanimity stalled the acceptance of the Articles until 1781. 2. Taxation and Requisition—Congress had to be sensitive to the language of the Revolution, which denounced taxation by a distant and nonrepresentative power; the congress would requisition (request) money to be paid into the common treasury; each state legislature would levy taxes within its borders to pay requisition; no mechanism compelled states to pay. B. The Problem of Western Lands Page 211 1. Western Land Claims—The Articles had no plan for the lands to the west of the thirteen original states; many states claimed those lands; five states had no claims, and they wanted congress to hold the land in a national domain and eventually sell the land to form new states. 2. Compromise and Conflict—States with claims finally compromised; any land a state volunteered to relinquish would become the national domain; Madison and Jefferson ceded Virginia’s huge land claim in 1781; Articles finally approved; conflict demonstrated the differences between the states. C. Running the New Government (Slide 5) Page 211 1. The Problems of the New Government—State legislatures were slow to select delegates; many politicians preferred to devote their energies to state governments, believing the real power was at the state level; often, too few representatives showed up to conduct business; the congress had no permanent home. 1 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 2. Attempts to Fix the Problems—Congress created executive departments of war, finance, and foreign affairs; the departments handled purely administrative functions, but their formation demonstrated that the congress was inventing a modest executive branch by necessity. II. The Sovereign States (Slide 7) Page 213 A. The State Constitutions 1. Republicanism—By 1778, all states had drawn up constitutions; having been denied the unwritten rights of Englishmen, Americans wanted written contracts that guaranteed basic principles; all state constitutions stipulated that government ultimately rested on the consent of the governed; political writers embraced the concept of republicanism as the underpinning of the new governments; republicanism meant different things to different people, but all proponents believed that a republican government was one that promoted the people’s welfare. 2. How to Best Serve the People—Leaders agreed that republics could succeed only in small units so people could make sure their interests were being served; most states limited the term length and powers of the governor; real power resided with the lower houses, which were more responsive to popular majorities, with annual elections and guaranteed rotation in office. 3. Bills of Rights—Six state constitutions included bills of rights, which were lists of basic individual liberties that government could not abridge; Virginia passed the first bill of rights in June 1776; guaranteed freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and trial by jury. B. Who Are “the People”? Page 214 1. Property—Limits to participation were widely agreed upon in the 1770s; in nearly every state, candidates for the highest offices had to meet substantial property qualifications; only property owners were presumed to possess the necessary independence of mind to make wise political choices; qualifications probably disfranchised from one-quarter to one-half of all adult white males in the United States; made voting class specific. 2. Gender—Few stopped to question excluding women from voting; only three states specified that voters had to be male, as the assumption was unspoken. 3. New Jersey—State constitution enfranchised all free inhabitants worth more than £50; opened the door for unmarried women and free blacks; a 1790 law used the language he or she, making woman suffrage explicit; small numbers of free blacks and women made their influence small, but a new state law explicitly disfranchised blacks and women in 1807. 2 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes C. Equality and Slavery (Slide 8) Page 216 1. Did Bills of Rights Apply to Slaves?—No; referred to white Americans; Virginia legislators explicitly excluded slaves from civil society. 2. Challenging Slavery—The Revolutionary ideals about natural equality and liberty encouraged a legal assault on slavery; slaves in the North filed petitions to obtain their freedom, but they were not successful; slaves in Massachusetts found success suing for freedom in the courts; slavery in Massachusetts was effectively abolished by judicial decisions by 1789. 3. Gradual Emancipation—Pennsylvania passed its first gradual emancipation law in 1780; freed children of slave mothers once they reached age 28; many slaves simply ran away from their owners and claimed freedom; other northern states followed with gradual emancipation laws. 4. Resistance to Emancipation—Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia rejected emancipation bills; slavery was central to the economy; the states did ease restrictions on individual acts of emancipation; by 1790, close to 10,000 newly freed Virginia slaves had formed local free black communities with schools and churches; in the deep South of the Carolinas and Georgia, freeing the slaves was unthinkable for whites. 5. Symbolic Importance—Every state from Pennsylvania north acknowledged that slavery was fundamentally inconsistent with Revolutionary ideology; also led to a geographic divide that associated the North with freedom and the South with slavery. III. The Confederation’s Problems (Slide 11) Page 218 A. The War Debt and the Newburgh Conspiracy Page 219 1. Soldiers’ Back Pay—For nearly two years, the Continental army camped at Newburgh, New York, awaiting the finalized peace treaty; they were angry at the prospect of not receiving their pensions due to the unstable economy; in December 1782, officers petitioned the congress for immediate back pay for their men; the congress hoped they could use this sympathetic story to make a case to the states for taxation. 2. A five percent impost—Philadelphia merchant Robert Morris was the superintendent of finance; led an effort to collect a 5 percent impost (import tax), but it failed by one vote each time; showed how unworkable the amendment provision of the Articles was. 3 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 3. A Threatened Coup—The Newburgh Conspiracy marked the country’s first and only instance of a threatened military coup; no actual coup was envisioned; Morris and other congressmen offered encouragement to officers to act as if the army would march on the congress to demand its back pay. 4. Washington’s Response—Washington signed the initial petition but did not know that the leaders of the planned march were in collusion with congressional leaders; in March 1783, he learned of these developments and delivered an emotional speech to five hundred officers; asserted that civilian government takes precedence over the military; defused crisis. B. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix Page 220 1. Disputed Lands—Indians had been excluded from the Treaty of Paris; confederation government wanted to end hostilities and secure land cessions, particularly from the Iroquois; the government wanted to take advantage of the revenue that land sales would generate. 2. Two Meetings at Fort Stanwix—The congress summoned Iroquois to a meeting in October 1784 at Fort Stanwix; the governor of New York argued that New York Indians should only negotiate with the state of New York and called his own meeting at Fort Stanwix in September; Iroquois knew the September meeting would be superseded by the congress; sent deputies without negotiating power. 3. American Demands—In October, Americans demanded a return of prisoners of war, recognition of the confederation’s power to negotiate (rather than that of the individual states), and a cession of Indian land from Fort Niagara due south; land would establish the U.S. border with Canada and encircle Iroquois land within the United States; argued the Indians were a subdued people. 4. A Contested Treaty—Indians balked but ultimately signed the treaty; tribes not at the meeting tried to disavow the treaty as a document signed under coercion by virtual hostages; the confederation government ignored them and made plans to survey and develop the Ohio territory; New York leaders astutely understood that the confederation government lacked the resources to implement the treaty terms; quietly began surveying and selling the very land they had failed to secure from the Indians in September; exposed another weakness in the confederation government. C. Land Ordinances and the Northwest Territory (Slide 13) Page 222 1. Jefferson’s Plan—Thomas Jefferson drafted a policy for expanding westward; he proposed dividing the territory north of the Ohio River and east of the 4 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes Mississippi (called the Northwest Territory) into nine new states with evenly spaced east-west boundaries and townships ten miles square; first encouraged giving land to settlers rather than selling it to build a nation of freeholders and discourage speculation; the draft guaranteed self-government and prohibited slavery in the territory. 2. Land Ordinance of 1784—Incorporated parts of Jefferson’s plan; found too radical the proposal to give away the land; slavery prohibition failed as well. 3. Land Ordinance of 1785—Revisions of the 1784 plan; called for dividing the land into three to five states; land would be sold by public auction for a minimum price of one dollar an acre; minimum purchase was 640 acres, and payment had to be made in hard money or certificates of debt; gave the advantage to speculators, who held the land for sale rather than living on it; thus avoided conflict with Indians who called the land their own. 4. Land Ordinance of 1787 (the Northwest Ordinance)—Set forth the process by which settled territories would advance to statehood; population would eventually write a constitution and apply for full admission to the Union; perhaps the most important legislation passed by confederation government; ensured United States would not become a colonial power with respect to its white citizens. 5. Indians—Indians were acknowledged, but their land claims were not protected or honored. 6. Slavery and the Roots of North-South Sectionalism—The ordinance prohibited slavery but came with a fugitive slave law; acknowledged and supported slavery even as it barred it from one region. D. The Requisition of 1785 and Shays’s Rebellion, 1786–1787 (Slide 17) Page 225 1. Requesting Money from the States—In 1785, the confederation government requested $3 million from the states, four times larger than the previous year’s requisition; needed the money for operating the government, paying debts owed to foreign leaders, and paying Americans who owned government bonds; at the same time, states were struggling under state tax levies. 2. Tension in Massachusetts—Massachusetts saw most extreme tensions; fiscally conservative legislature had passed tough tax laws four years in a row; in March 1786, the legislature in Boston loaded the federal requisition onto the bill. 3. Protests in Western Massachusetts—Farmers in the western two-thirds of the state petitioned Boston for relief and held conventions calling for democratic revisions to the state constitution; also wanted the capital moved farther west in 5 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes the state; still unheard, the dissidents in six counties targeted the county courts; forced them to close their doors until the state constitution was revised. 4. Response from State and Federal Governments—Governor James Bowdoin had organized protests against British taxes; now characterized western dissidents as rebels; vilified the chief leader Daniel Shays; Continental Congress feared armed revolt and called for enlistments to triple the size of the army; fewer than 100 men responded; Bowdoin also raised private army of 3,000 men, whose pay was provided by wealthy and fearful Boston merchants. 5. Shays’s Rebellion and Its Aftermath—Insurgents learned of the private army marching west in January 1787; moved to capture a federal armory to obtain weapons; met with gunfire from a militia; four rebels killed and another 20 wounded; in the end, two rebels were executed for rebellion; 4,000 men gained leniency for confessing misconduct; Shays himself escaped to Vermont; the rebellion was significant, in that it caused colonial leaders to worry about the confederation’s ability to handle civil disorder. IV. The United States Constitution (Slide 19) Page 227 A. From Annapolis to Philadelphia 1. Revision Meetings—James Madison and Virginians convinced the congress to allow a meeting of delegates in Annapolis in September 1786 to revise the trade regulation powers of the articles; only five states participated; rescheduled the meeting for May 1787 in Philadelphia; the congress reluctantly endorsed the meeting and limited its scope to revising the Articles; Alexander Hamilton of New York attended with hopes for a stronger government. 2. The Constitutional Convention—The fifty-five men who met in Philadelphia had already concluded weaknesses in the Articles; all white men; generally wealthy; two-thirds were lawyers and the majority had served in the Confederation Congress and knew its strengths and weaknesses. B. The Virginia and New Jersey Plans Page 228 1. Virginia Plan—The Philadelphia convention worked in secrecy so that the men could freely explore alternatives without fear their honest opinions would come back to haunt them; major issue was representation; Virginia Plan repudiated the principle of a confederation of states; called for a two-chamber legislature, a powerful executive, and a judiciary; practically silenced the smaller states by linking representation to population; argued government operated directly on the people, not on the states. 6 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes 2. New Jersey Plan—In mid-June, delegates from small states unveiled the New Jersey Plan; maintained the single-house congress of the Articles, but gave it sweeping powers; also called for a plural presidency. 3. The Great Compromise—Solved the deadlock between large and small states in mid-July; produced the basic structural features of the emerging U.S. Constitution; bicameral legislature, with representation in the lower house, the House of Representatives, tied to population and representation in the upper house, the Senate, coming from all states equally. 4. The Three-Fifths Clause—Determined how slaves were counted as people and property; all free persons plus “three-fifths of all other Persons” would constitute the numerical apportionment of representatives; using the phrase “all other Persons” as a substitute for “slaves” indicates the discomfort delegates felt in acknowledging in the Constitution the existence of slavery; the words slave and slavery never appear, but the Constitution recognized and guaranteed slavery with the fugitive slave clause and a provision closing the international, but not the domestic, slave trade. C. Democracy versus Republicanism (Slide 20) Page 230 1. Republican Institutions—Delegates saw pure democracy as a dangerous thing; favored republican institutions, but created a government that gave a direct voice to the people only in the House; gave a check on that voice by the Senate, a body of men elected not by popular vote but by state legislatures; presidency also out of reach of direct democracy due to the electoral college. 2. Checks and Balances and Enumeration of Powers—Government had limits and checks on all three of its branches; convention listed the powers of the president and of Congress; only three dissenters refused to sign the document; only nine states, not thirteen, would need to ratify the document; votes would come from special ratifying conventions, not state legislatures. V. Ratification of the Constitution (Slide 21) Page 231 A. The Federalists 1. Marshaling Support—To silence critics, supporters sent the document to the congress; pro-Constitution forces called themselves Federalists; opponents thus were called Antifederalists, which made them appear defensive and negative. 2. Ratification Strategy—The Federalists targeted states most likely to ratify quickly; by early 1788, they had achieved ratification in Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, Maryland, and South Carolina; after a tough battle, they secured ratification in Massachusetts by May 1788; they therefore 7 of 8 The American Promise – Lecture Notes only needed one more vote, but they also felt they had to win over the largest and most economically critical states: Virginia and New York. B. The Antifederalists Page 232 1. Who Were the Antifederalists?—The Antifederalists were a group united mainly in their desire to block the Constitution; they drew strength from the longnurtured fear that distant power might infringe on people’s liberties. 2. Elected Officials and Individual Rights—Antifederalists feared that representatives would always be elites and therefore not sensitive to the problems of the lower classes; Federalists agreed that elites would be favored in national elections, but they viewed it as a good thing; Federalists wanted power to reside with intelligent, virtuous leaders like themselves; Antifederalists’ most widespread objection was the Constitution’s omission of any guarantee of individual liberties like those found in state constitutions’ bills of rights. C. The Big Holdouts: Virginia and New York (Slide 23) Page 234 1. New Amendments in Virginia—New Hampshire cast the decisive vote on June 21, 1788, but New York and Virginia were too large and important to ignore; an influential Antifederalist group led by Patrick Henry and George Mason tried to block the Constitution; Federalists finally secured ratification by proposing twenty specific amendments that the new government would promise to consider. 2. New York and The Federalist Papers—New York voters believed such a large state should not relinquish so much power to the new federal government; also home to persuasive Federalists; Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay wrote and published eighty-five essays on the political philosophy of the new constitution; the essays were later republished as The Federalist Papers; Madison argued in Federalist 10 that a large republic would increase democracy by preventing a single faction from coming to power; impassioned debate plus the news of Virginia’s ratification tipped the balance to the federalists. 3. Ratification—Took another year and a half for Antifederalists in North Carolina to come around; Rhode Island held out until May 1790, and even then it ratified by only a two-vote margin. 8 of 8