Urban Event s Teachers Enacting Project-Based Science

advertisement

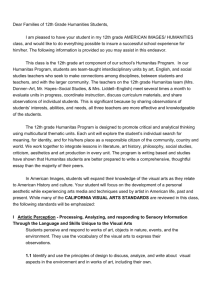

Afrodita Fuentes SED 625SC 12/13/06 Humanitas Program Model – Conference Because the Humanitas Program will be adopted by the small learning community, I need to develop a great understanding of it, hence the lengthy theory in this paper. I sought more information in addition to what was provided by the presenters. Humanitas in the Age of Enlightment meant “good human.” The humanities is known as a group of academic subjects with the common goal of studying aspects of the human condition, avoiding a single pattern of thought to define any discipline. It includes subjects such as the classics, languages, literature, music, philosophy, performing arts, religion, and the visual arts. It also involves the social sciences such as archaeology, area studies, communications, cultural studies, and history. Summary In Los Angeles, the Humanitas program began in 1986 under the joint sponsorship of the Los Angeles Educational Partnership (LAEP) and the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). It engages more than 500 teachers and 10,000 students in 31 LAUSD schools. Cleveland High School and Roosevelt High School have two Teacher Training Centers that guide new teachers into the program. While the program has mostly involved the social sciences, it is now including the natural sciences. In this conference, a team of two teachers, an English teacher and a Marine Biology teacher, presented the Humanitas program. The Humanitas program is a model that provides teachers with a framework for creating interdisciplinary, thematic, team-taught, writing-based humanities instruction. Teams of teachers (in different disciplines) work to define themes of study, plan interdisciplinary units, and implement those units using strategies that actively involve students in the classroom. Teachers select appropriate student materials that highlight the themes of study and that are interesting to students. Themes of study engage, interest, and involve students in discussion. Some components of the Humanitas curriculum include building vocabulary, writing-based instruction, teaching methodologies and engaging students, interdisciplinary curriculum trips, and interdisciplinary exams (essays). The purpose of building vocabulary is to give students more control over their lives and surroundings. The Humanitas program believes that students need to have authority and abilities to define themselves and the world around them in an oral and written form. To help students do that, teacher team members reinforce vocabulary throughout their lessons as groups of students rotate classes. Teachers encourage students to use vocabulary words in essays and when speaking in and outside of class. The Humanitas curriculum provides numerous diverse writing experiences to help learners develop their subject-matter and interdisciplinary understanding, as well as to express themselves. The following strategies are suggested to help students write. The writing process involves “rewriting,” “writing,” and post-writing/editing,” which has two roles. One is to create an outline to produce a writing piece with substance and the other is to model careful thought. Teachers build scaffolds that deepen and broaden student understanding and ability to articulate, and provide students with meaningful writing experiences daily. Students work collaboratively and may look at visual aids to boost language to write. Teachers also keep in mind the four major forms of discourse: description, narration, exposition, and persuasion. Students are also exposed to the variety of written domains: autobiographical narration, evaluative writing, interpretive writing, observational writing, reflective writing, and speculative writing. Writing is also required before, during, and after an interdisciplinary curricular trip. Usually the final assessment is an interdisciplinary essay. Selecting a good theme, using appropriate materials, and writing solid interdisciplinary essay questions are essential but no sufficient to accommodate the many motivational and learning styles of students. Effective teaching strategies are essential, such as creating a student-focus environment that fosters the auditory learner, the visual learner, the kinesthetic learner, etc. To motivate students, themes should involve students in debate because those themes are part of their everyday life. Teachers need to create and atmosphere of anticipation and some unpredictability. Since theme is what sparks students’ interest academically, the following are science themes explored in units implemented by teachers in the Humanitas program according to the speakers, English teacher and marine biology teacher: Unit Theme Disciplines Incorporated Grade Level Team (teachers & students) The Question of Human English, Creative writing, biology 10 Behavior/Nature Origins, Present Status and Possible Life science, biology, English, social 10 Future studies Origins: Where did We Come From? English, biology, humanities 11 Culture: the Human Mosaic Biology, American history, art 11 history, US history I love Mystery! Integrating Human Literature, biology, fine arts 12 Knowledge and Experience Through a Criminal Investigation The two teacher presenters shared an outline of their year long curriculum. Their year long theme is “The life of the sea: source and metaphor for life.” The Thematic question is “What is the life of the sea and what does the sea tell as about life? Units prepared, materials used, topics explored, activities, and their sequence are listed in the following table. Word Literature of the Sea class (senior English Marine Biology class (senior science elective). requirement) Intro Unit: Emotional Buoyancy Intro Unit: Physical Buoyancy Book: South by Ernest Shackleton & The Perfect Project: building a boat Storm by S. Junger Question: What lifts us up and what makes us sink? Myths/Legends/Stories of the Sea Rocky Shore, California Coastline Question: What is the relationship between the human and the wild? The Dark Side of the Sea by Moby Dick Deep Sea Marine Life Novel Unit: The Old Man and the Sea by Investigations: physical characteristics of marine life Hemingway around Cuba Narrative Poetry: the Rime of the Ancient Mariner Pelagic Birds and the Albatross and related material of the albatross Fisheries Unit: A case study – Cod by Mark Fisheries Kurlansky Town Hall Meeting: to fish or not to fish Environmental Literature: Al Gore, John Muir, Environmental pollution of the Ocean Edward Abbey, Gary Snyder, Thoreau Rachel Carson Assessment: Interdisciplinary essay assessed by both teachers Evaluation (strengths, weaknesses, suggestions) The promise of the Humanitas program seems incredible! It focuses on building a community of learners with the purpose of enriching their lives academically and socially. It also wishes to create individuals that have the necessary tools to define themselves and the world around them. The curriculum encourages the use of a variety of writing experiences a long with a plethora of strategies to help students create acceptable writing pieces that allow for student metacognition. The program claims to prepare students to be critical thinkers, problem solvers, excellent communicators in a diverse world, and resourceful individuals. The presenters seemed very enthusiastic to share their work. They also invited members of other teams in the program to share student work such as student created personalized props to empower them in a literature class and interactive notebooks used in a social studies class to internalized progression and application of topics. That was very powerful. The success of the program is unknown. There has not been any studies of the impact of this program in the past ten years. I contacted the offices of LAEP, but only provided draft studies report done by UCLA in 1994. Humanitas seems to be a very complex program to implement because it requires a team of teachers working together constantly (for the two presenters, working together was easy since they were married). Working in teams requires tremendous cooperation, time, and funds, which were topics that were avoided or dismissed during the presentation. It also seems like the Humanitas teams of students excludes those in special education and language learners. Questions were raised about this, but the answers were unclear and did not seem practical. Also, outlines of thematic units seemed outdated. For example a unit was prepared by a teacher who has not worked at my school for at least eight years. An SLC at my school uses Humanitas, but the biology teacher in it doesn’t seem to do any interesting projects. A few students who are taking AP Biology with me claim to not have studied essential topics in their regular biology class with that teacher, but that they enjoyed topics discussed and explored in their social studies class and English class – taught by respected teachers. That shows that to implement the program sacrifices content material or that teachers need to be committed educate students appropriately. I would suggest for LAEP to provide data showing the success of Humanitas. I would like to see how exactly students are selected to be in the program, how many of them stay in the program, how students improved, how many of them continued their education, and how many of them earned degrees that led them to have successful lives. Personal Application Response In theory, the Humanitas program sounds wonderful, but what does it really take to make it a reality and show the results that it promises? The ultimate engines of the program seem to be the teachers who need to spend unlimited time planning, evaluating, and revising their curriculum. Finding time to plan is very difficult. Most teachers do not want to spend their time planning after school, on the weekends, or their vacation without pay. I’m trying to get together with two teachers. One of them cannot meet until January, but is open to whatever ideas I come up with. The other must be out of the country because he has not responded to my messages. So, what kind of team is that? Perhaps, if they were offered pay, they would be here? And that is just part of the problem, scheduling classes is a monumental problem at my huge school with a not so helpful head counselor and a few demanding lead teachers of other SLCs. What will take to make the results of Humanitas a reality in my SLC and my classroom? I believe our SLC has taken the first two steps towards Humanitas. We know to create students who are critical thinkers, problem solvers, excellent communicators in more than one language, and resourceful. We want them to be able to function in a rapidly changing world. We have also identified our grade level teams. The 9th grade team has superficially defined a few themes. The 10th grade and 11th grade themes have been identified, but now they need to plan units together. We need to recruit teachers for a 12th grade team. I will continue planning my units and encouraging my team to meet and plan together. I am very excited to begin working with the English teacher in my team because he is an excellent from who students learn to become amazing writers. Planning with him with Humanitas in mind, I anticipate it to be a very stimulating learning experience for me. I can’t imagine how wonderful it will be for our students if our work is done correctly.