Reading 1: Bi-Lingual Resonance ppt poster

advertisement

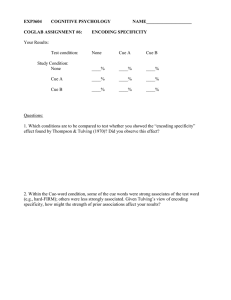

Bilingual Resonance: Reactivating Text Elements Between L1 & L2 R. Brooke Lea (Macalester College), Paul van den Broek, Jazmin Cevasco (University of Minnesota), & Aaron Mitchel (The Pennsylvania State University) Resonance Background • Recent studies addressed the question of how readers access information from long term memory (e.g., Albrecht & Myers, 1995; Lea et al., 1998; McKoon et al., 1996). •For example, Albrecht & Myers (1995) showed that small contextual cues (e.g., “leather couch”) could reinstate unsatisfied goals that had been backgrounded in a long passage. •Their experimental strategy was to present readers with target sentences that would appear inconsistent only if the participant remembered the unsatisfied goal. •The results showed that readings times on those target sentences were significantly slower when the contextual cue was presented just before the sentence. •The cue reminded readers of the unsatisfied goal. •The authors discussed their results in terms of a resonance process that activates propositions in memory that overlap with propositions in working memory. It was temporarily quiet on the battlefront. The young lieutenant in charge of the unit realized that they were short of ammunition. Because he had word that the enemy would counterattack the next morning, he would have to go to headquarters before sundown to request more ammunition for the unit. He got in an old dirty jeep and sped toward headquarters. He hadn't gotten far when he spotted a badly wounded soldier who clearly needed immediate attention. Tendría que ir al cuartel general después de encontrar a alguien que atendiera al soldado. El teniente buscó un médico, pero no lo halló. Mientras tanto, el soldado herido estaba sangrando mucho. El teniente rasgó en pedazos la camisa del soldado en pedazos y envolvió firmemente la herida con ellos. Finalmente, observó complacido que el soldado dejaba de sangrar. En ese momento, un médico llegó y relevó al cansado teniente. El teniente regresó en el viejo y sucio jeep y encontró un lugar para tomar una rápida siesta. No había dormido por varios días. Al día siguiente, probablemente habría mas batalla. Spanish/English El frente de batalla estaba temporalmente tranquilo. El joven teniente a cargo de la unidad se dio cuenta de que las municiones estaban escaseando. Dado que sabía que el enemigo contraatacaría a la mañana siguiente, tendría que ir al cuartel general antes del anochecer para conseguir mas municiones para la unidad. Se subió a un viejo y sucio jeep y se dirigió rápidamente hacia el cuartel general. No había llegado muy lejos, cuando vio un soldado mal herido que claramente necesitaba atención inmediata. He would have to drive to headquarters after he found someone to tend to the soldier. The lieutenant looked for a medic but there was none around. Meanwhile, the wounded soldier was bleeding badly. The lieutenant tore the soldier's shirt in strips and wrapped it tightly around the wound. Finally, he was pleased to see the bleeding stop. At that point, a medic arrived and took over from the tired lieutenant. The lieutenant got back in the old dirty jeep and found a place to take a quick nap. He had not slept for several days. Tomorrow there would probably be more fighting. Bilingualism Background • A central debate in bilingualism research concerns the nature of mental representations for multiple languages (Francis, 1999). • Considerable debate as to whether lexical activation is selective with respect to language -both lexicons activated simultaneously, and in parallel, or do bilingual speakers only activate the target language? • Recent research suggest that bilingual speakers activate both languages simultaneously (e.g. Jared & Kroll, 2001). • And evidence from the visual world paradigm that bilinguals, even in purely monolingual contexts, cannot “turn off” the non-target language (Spivey & Marian, 1999; Marian & Spivey, 2003). • These findings are captured in the latest Bilingual Interactive Activation (BIA +) model of language comprehension (Dijkstra & Van Heuven, 2002), which predicts simultaneous activation of both languages, with a language node cuing the target language and allowing for correct lexical selection (see Figure 1). • While not much research exists on bilingual lexical access during reading, there is evidence that lexical activation while reading is non-selective (Durgunoğlu, 1997). •If bilinguals activate both languages in parallel, then when reading a passage that switches between languages, do they make global inferences across languages? Figure 1. The BIA+ Model (adapted from Dijkstra & Van Heuven, 2002) Task schemaSpecifies processing steps for task at hand • • Receives continuous input from the identification system • Decision criteria determine when a response is made based on relevant codes Identification System Language nodes L1/L2 Semantics Lexical Orthography Lexical Phonology Sublexical Orthography Sublexical Phonology 3000 • Four language combinations: English-English (E-E); EnglishSpanish (E-S); Spanish-English (S-E); Spanish-Spanish (S-S) 2955 2712 2378 2299 2500 Design. 2 (cue) X 2 (First Half Language) X 2 (Second Half Language) first two factors within-, third between-subjects. 2000 15411409 1500 1526 1330 1000 500 0 Eng/Eng Eng/Span cue Span/Eng Span/Span no cue Results: Experiment 1 (See Figures 2 - 4) • Main effect for cue: F (1, 39) = 9.30, p = .004 • Significant cue-effect in all language combination conditions. • No interactions. • No relationship between L2 proficiency and size of cue effect. • Resonance clearly cross the bi-lingual divide. • Proficiency at this level is not related to the cue effect. Figure 3 Experiment 1: Cue Effects (Cue Effect = Cue – No Cue) 577.71 600 500 412.72 400 300 200 206.25 132.18 0 Eng/Eng Eng/Span Span/Eng Span/Span Figure 4 Experiment 1: Relationship Between L2 Proficiency and Cue Effects 3500 • Exp 2 subjects were significantly less proficient in Spanish; average CBM score in Experiment 2 was 99 compared to 128 words in Experiment 1, (t (88) = 5.17, p < .001). • Subjects took a vocab test of the 24 cue words; only subjects who scored 24 out of 24 on this test were included in the analyses. • Pattern of means was similar to Experiment 1 (Figure 5). • Significant main effect for cue: F (1, 47) = 10.51, p = .002. •Language-Congruence X Cue Interaction (Figure 8) approaching significance, F (1, 47) = 1.90, p = .177. • Significant cue effect in all four language combination conditions. • L2 proficiency and cue effect DID SHOW a significant positive correlation (Figure 7). • Hints at a connection between L2 proficiency and the effectiveness of contextual cues. Experiments 1 & 2 r = .081 • Combining Experiments 1 & 2: • Main Effect for Language Congruence, F >10 (Single Language texts slower than Mixed texts) • Main Effect for Cue, F >20 (Cue slower than No Cue). • Marginal Language Congruence X Cue interaction, p = .098, (Cue effect was larger in Single-Language texts than in Mixed texts; Figure 8.) • No significant differences between Exps 1& 2, except for correlation between L2 proficiency and cue effect in Spanish texts. r = -.128 3135 2912 2581 3000 2546 2500 2000 1581 1500 1513 1315 1442 1000 500 0 Eng/Eng Eng/Span Span/Eng cue Span/Span no cue r = .541 p = .003 Figure 6 Experiment 2: Cue Effects (Cue Effect = Cue – No Cue) 588.95 600 500 400 316.18 300 198.25 200 139.24 r = .450 100 p = .016 0 Eng/Eng Eng/Span Span/Eng Span/Span Figure 8 Conclusions Cue Effects for Single-Language vs. Mixed-Language Texts (Cue Effect = Cue – No Cue) Bottom-up reactivation processes like Resonance appear not to be affected in bilingual contexts. Reactivation effects in the mixed-language passages show that contextual cues need not share orthographic, phonemic, or languagespecific features to effectively reinstate backgrounded concepts. Such results suggest that Resonance can operate at an abstract, conceptual level; no overlap other than meaning appeared in the mixed-language texts. However, the marginal language-congruence X cue interaction may indicate that the additional overlapping features in the samelanguage texts provided stronger cues. These reactivation effects do not require a very high level of proficiency in L2 (found in students of 2nd semester college Spanish). The cue-effect is not related to language proficiency at relatively high levels of L2 ability; at lower L2 skill levels, proficiency is associated with a larger cue effect (this may be due in part to the task). These results provide further evidence for parallel, non-selective access models of bilingual processing. 500 398 426 400 References Albrecht, J.E., & Myers, J.L. (1995). The role of context in accessing distant information during reading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition,21, 1459-1468. Dijkstra, A., & Van Heuven, W. J. B. (2002). The architecture of the bilingual word recognition system: From identification to decision. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 5, 175-197. Durgunoğlu, A. Y. (1997). Bilingual reading: Its components, development, and other issues. In A. De Groot & J. Kroll (eds.), Tutorials in bilingualism. Psycholinguistic perspectives, pp 255-276. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Francis, W. S. (1999). Cognitive integration of language and memory in bilinguals: Semantic representation. Psychological bulletin, 125(2), 193-222. Jared, D. & Kroll, J. F. (2001). Do bilinguals activate phonological representations in one or both of their languages when naming words? Journal of Memory and Language, 44, 2-31. Lea, R. B., Mason, R.A., Albrecht, J.E., Birch, S.L., & Myers, J.L., (1998). Who knows what about whom: What role does common ground play in accessing distant information? Journal of Memory & Language, 39, 70-84. Marian, V., & Spivey, M. (2003). Bilingual and monolingual processing of competing lexical items. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24(2), 173-193. McKoon, G., Gerrig, R.J., & Greene, S.B. (1996). Pronoun resolution without pronouns: Some consequences of memory-based text processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition, 22, 919-932. Spivey, M. J., & Marian, V. (1999). Cross talk between native and second languages: Partial activation of an irrelevant lexicon. Psychological Science, 10(3), 281-284 Experiment 2: Relationship Between L2 Proficiency and Cue Effects Results: Experiment 2 (See Figures 5 - 7) 100 • Within each of the four combinations, half of the passages were “cue” and half were “no-cue” Why no L2 proficiency – cue-effect correlation? Perhaps lack of proficiency range Lower proficiency subjects in Experiment 2 Forty-nine students from intermediate-level Spanish classes at Macalester – in second semester of college Spanish Subjects were proficient enough to understand the stories, but less proficient than those used in Experiment 1. Milliseconds English/Spanish Figure 7 Experiment 2: Target Sentence Reading Times Experiment 1: Target Sentence Reading Times Subjects. 41 students from upper-level Spanish classes at Macalester College participated for $10. They were all native speakers of English (L1), and highly proficient in Spanish (L2). Materials. Passages from Albrecht and Myers (1995) were adapted by translating them into Spanish (see Table 1). The passages each contained: Introduction: with an unsatisfied goal, and the contextual cue (e.g., “old, dirty jeep”) • Intervening Episode • Conclusion: contextual cue is present or absent • Target Sentences: coherent, but not globally coherent if the reader reactivates the backgrounded goal. Target sentence reading times slower if readers are reminded of the global anomaly. • 24 experimental passages and 14 fillers. • Spanish proficiency measured with the CBM reading test. Figure 5 Milliseconds It was temporarily quiet on the battlefront. The young lieutenant in charge of the unit realized that they were short of ammunition. Because he had word that the enemy would counterattack the next morning, he would have to go to headquarters before sundown to request more ammunition for the unit. He got in an old dirty jeep and sped toward headquarters. He hadn't gotten far when he spotted a badly wounded soldier who clearly needed immediate attention. He would have to drive to headquarters after he found someone to tend to the soldier. The lieutenant looked for a medic but there was none around. Meanwhile, the wounded soldier was bleeding badly. The lieutenant tore the soldier's shirt in strips and wrapped it tightly around the wound. Finally, he was pleased to see the bleeding stop. At that point, a medic arrived and took over from the tired lieutenant. The lieutenant got back in the old dirty jeep and found a place to take a quick nap. He had not slept for several days. Tomorrow there would probably be more fighting. Experiment 2: Less Proficient Readers Figure 2 Milliseconds English/English Experiment 1 Milliseconds Memory-based text processing research has focused on how distal text concepts are reactivated by an automatic resonance process. In a typical experiment, an adjective-noun pair such as “leather couch” is presented as a contextual cue early in a passage, and then repeated later in the passage. Concepts associated with the first instance of the cue are reactivated upon presentation of the second instance of the cue. Researchers agree that feature overlap is fundamental to triggering resonance, but little is known about how overlap is defined psychologically. We gave English-Spanish bilinguals passages that were partly in English and partly in Spanish, and crossed L1 and L2 with the beginning and end of each passage to determine the effect that cue encoding in one language has on the translated counterpart encoded in the other language. The results showed robust resonance effects both within and between languages, and a modest L2 proficiency effect. Table 1 Example Texts Used in Experiments 1 & 2 Milliseconds Abstract 307 266 300 200 100 0 Single Language Exp. 1 Mixed Languages Exp. 2