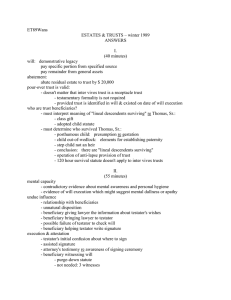

Sitkoff

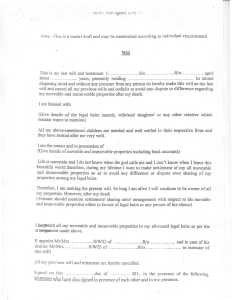

advertisement