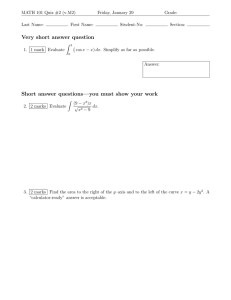

Michael Petrocelli Trademarks Outline – Prof. Reese Fall 2006

advertisement