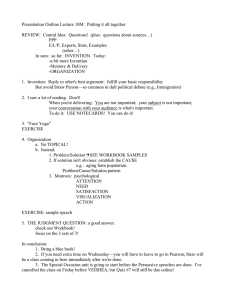

IP SURVEY—Dreyfuss—Fall 97

advertisement