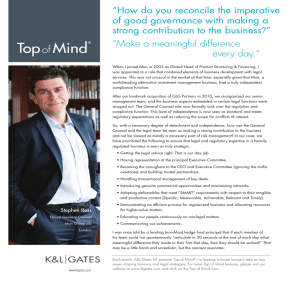

Subin

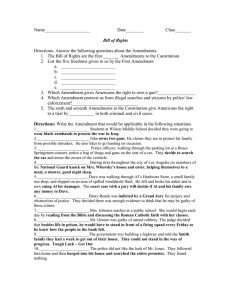

advertisement