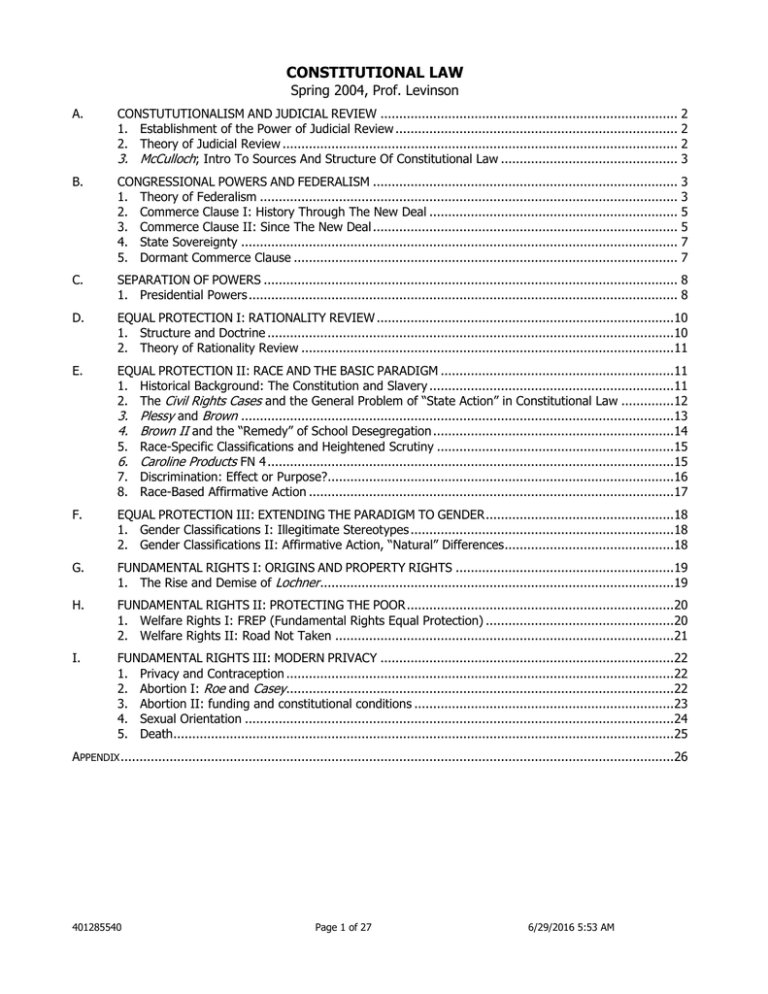

Levinson

advertisement