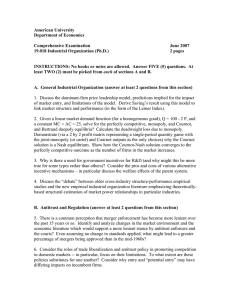

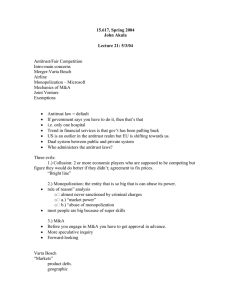

Antitrust I, Fox Fall 2000 Nichelle Nicholes Levy

advertisement