Baker

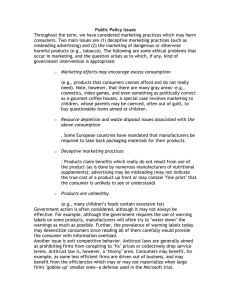

advertisement