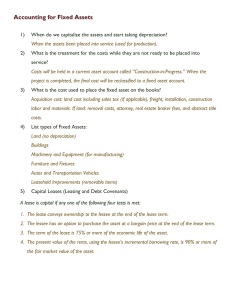

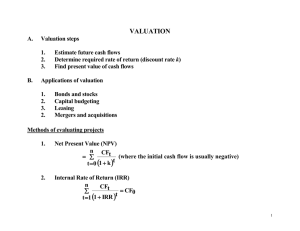

Accounting Outline Prof. Siegel Spring 2006

advertisement