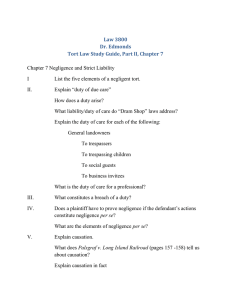

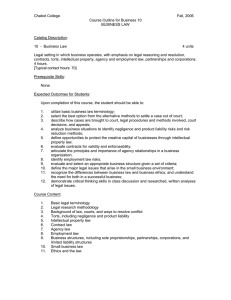

Torts Outline A) Definitions:

advertisement