Intentional Torts: Battery

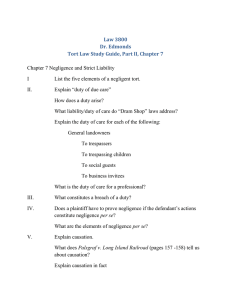

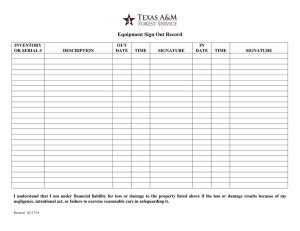

advertisement