I. Intentional Torts

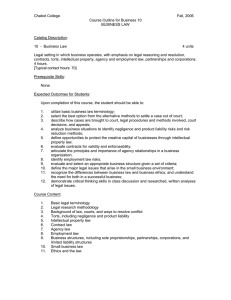

advertisement