Thompson Crim Outline

advertisement

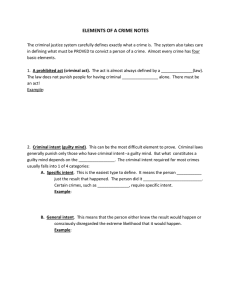

Thompson Crim Outline Civil v. Criminal Law Since Criminal Law involves using the coercive power of the state against individuals, it has significantly stronger protections for individual rights. • Civil law covers disputes among private parties. Criminal law is state v. citizen. Prosecutors have lots of discretion and represent the state. • Criminal Law has a much higher burden of proof: beyond a reasonable doubt rather than preponderence of evidence. Even if you can’t get someone for a crime, you can often get him in a civil suit. • Civil law assesses compensatory damages, rarely punitive. Criminal law is all about punishment. And lifelong stigma. • Much of civil law comes from the common law – judges’ decisions. Criminal law largely doesn’t allow common law crimes. • Civil law isn’t impacted that much by the Constitution. But the bill of rights and habeas corpus are huge in criminal law. • No consent defense in criminal law. • No comparative liability in criminal law. • Causation isn’t central in criminal law. • Unlike torts, Strict Liability is in decline. • Criminal law isn’t ultimately about harm to individuals, but rather harm to society. Principle of Legality For criminal liability, a reasonably specific law making the conduct criminal must exist at the time of the conduct. • If there isn’t notice, there’s a due process issue. Also an ex post facto issue. • Question of whether we allow common-law (judicially created) crimes. Most states do not allow this, though some do. Commonwealth v. Mochan. UK does allow, but happens rarely. Shaw. • Example of homicide statute in Keeler v. Superior Ct. Didn’t clearly cover the unborn, so can’t apply it to defendant. Vagueness Doctrine A law that renders certain acts criminal must be reasonably specific. • Has to be fair warning. Otherwise the potential for tyranny is too high. Due process issue. • Linked to principle of lenity – ambiguous statutes interpreted in favor of the defendant. Example of McBoyle v. US – whether an airplane counted as a “vehicle” under the Nat’l Motor Vehicle Theft Act. Court says to apply there would be too vague. • Also the vagrancy statutes in Papachtistou and Morales. So vague that they could cover almost anything. Give too much discretion to the police. • That doesn’t mean everything has to be clear. Law can force people to guess how a jury would rule. Nash v. United States. Free Speech Doctrine/Overbreadth Doctrine Don’t want to criminalize protected speech and political acts. If a statute could be used to prohibit protected speech, can challenge Constitutionality. Principle of Lenity If a statute is unclear, then the ambiguity must be resolved in favor of the defendant. • Example of US v. Dauray, question of whether individual loose photos of kiddie porn count the same as a full magazine. It’s unclear, so court decides no. • If the statute is not clear, don’t want to give state power on the margins. • Only in a very close case. Still go through the whole statutory interpretation process. Purposes of the Criminal Law Retribution Reform/Rehabilitation By punishing someone, you impress on him People are moral actors and need to be the wrongness of what he’s done and teach punished based on the greviousness of their him to be a better person. deviations from morality. • This idea evolved out of Quaker moral • Strong retributivism – a culpable moral act thought and led to the penitentiary system. is necessary and sufficient for punishment. If • Doesn’t work with retributivism well – if there is no moral wrong, you can’t punish. If the guy is reformed, do you let him out? there is, you must punish. Kant. • American prisons aren’t effective at reform • Weak retributivism – The culpable moral at all – they actually create criminals. act is necessary but not sufficient. To deter• But once reform drops out as a rationale, mine whether and how much to punish, you discretionary sentencing is suspect. can look at deterrence, reform, etc. • Question of holding people to standards they can’t meet – Dudley and Stephens. Alternative Sentencing • Hart was a weak retributivist. DAR studied There are other penalties besides prison under Hart. and fines that could serve the purposes of the criminal law. • Example of shaming in Gementera, the Deterrence sandwich board case. Covers retribution and By punishing crimes, we deter people from deterrence. committing future crimes. • General deterrence – deterring others from committing future crimes. Harm Principle • Specific deterrence – deterring the specific J.S. Mill argues that an act may not be criminal from doing something again. criminalized unless it causes harm. • Retribution constrains deterrence. With • Uncertain about harm to self. deterrence alone, you could punish innocent • Devlin: society is based on shared moral people to deter others (or not punish people values. If you undermine those, it will disinand say you did.) tegrate. • Bentham – criminals make rational calcula• This has been vindicated over time. Wolftions. The law wants to make them decide enden commission. Griswold. Lawrence. not to commit crimes. (Roe?). • Two things necessary to deter – certainty that the criminal will be caught, and severity Right to Intimate Life of the punishment. Certainty deters more, but Richards views GriswoldRoeLawUS is better at severity than certainty. rence as reflecting a “right to intimate life” Incapacitation By imprisoning a criminal, we keep him from committing more crimes. • Scientific evidence seems to find this the aspect of our system that’s most successful. • Idea of keeping “career criminals” out of society until they grow out of it. But there’s a false positive problem. • What about crimes of passion? They won’t do it again. Why punish at all? in the Constitution that is protected from criminalization. And reflects the harm principle. • In many of these cases there isn’t a compelling nonsecular justification for criminalization. Roe is the obvious exception. Corporate Criminality There are very real harms in areas like products liability that have given rise to calls for vicatious liability of corporations and corporate executives. Does the harm principle mean they should be liable? Euthanasia Passive Euthanasia is allowed because there is a constitutional right to refuse treatment. Cruzan. But active euthanasia (helping someone to kill themselves) is not protected by the Constitution and states can prohibit it. Glucksberg. • There is a constitutional right to refuse treatment. At common law, forced medication was a battery. But there has to be “clear and convincing evidence” that the person wanted treatment stopped. • But there are real concerns about active euthanasia – medical ethics, potential for exploitation (people encouraging the elderly to die) and a slippery slope toward involuntary euthanasia. But the court left itself open to an as-applied case. Actus Reus Acts A person can only be held criminally liable if there is a culpable voluntary act. • Five exceptions: reflexes, unconsciousness, sleepwalking, being physically carried. • NY Penal law §15.10. • No actus reus is a complete defense. If it’s granted, the defendant walks free. • In Martin v. State, a statute criminalized anyone drunk on a highway. Martin is drunk, but cops carry martin onto a highway, then charge him. No actus reus. • Example of People v. Newton. Newton claimed he was in shock and didn’t remember anything. Was entitled to raise that defense (unconsciousness). • Prior knowledge can get around an actus reus issue. Decina case – defendant got behind the wheel knowing she had epilepsy. Driving the car was the actus reus, knowledge was the mens rea. • There’s kind of a spectrum of voluntariness. Alcoholism Addiction Insanity Epilepsy. Concurrence Requirement To be liable, the defendant must have the mens rea at the time he commits the actus reus. • If I want to kill you, get over it, then have a non-negligent car accident later that day that kills the person, no liability. Status Crimes The Constitution requires an actus reus for criminal liability. Status crimes are unconstitutional. • Example of Robinson v. California, where a law making it illegal to be addicted to drugs was struck down. • But this isn’t the case for civil commitment. There sickness is enough. • Though there are limits to this and the actus reus can be weak. In Powell v. Texas, the court upholds an alcoholic’s conviction for being drunk in public. He might not have been able to control his drinking, but he acted by going out in public. And prison with a defined term might be better than inefinite civil commitment. Omissions There are four areas where an omission counts as an actus reus: 1) statutory obligations, 2) status obligations (e.g., being a parent), 3) Contractual obligations, and 4) Going to help or creating a risk. • Most cases do not extend status liability in a family beyond parents or spouses. • In Jones v. US, a baby gets left with Jones, a family friend. Jones doesn’t care for it. Baby dies. But Jones isn’t actually a parent, so no liability. • In Pope v. State, a non-mother sees a child badly beaten, does nothing, baby dies. No liability. • Question: is there contract/risk creation? • Reason for policy: want to encourage relationships. • In much of Europe, there is duty to aid. • Getting something defined as an omission makes it easier to get off. Example of doctors in Barber v. Superior Court who removed feeding tube. Mens Rea INTENT “A person acts intentionally…when his conscious objective is to cause such result or engage in such conduct.” NYPL § 15.05(1). • Can’t impute intent from one act to another. Regina v. Cunningham. One (BIG) exception: Felony Murder. • Substantial certainty doctrine: if defendant means to do everything up to an end and knew with a substantial certainty that the end would result, he is deemed to have intended that end. • Intent is different from motive. Intent means to intend something to happen. Motive is the reason for doing something. Motive comes in on sentencing. Deadly Weapon Doctrine Use of a deadly weapon creates a rebuttable presumption of intent to kill. KNOWLEDGE “A person acts knowingly…when he is aware that his conduct is of such nature or that such circumstance exists.” NYPL § 15.05(2). • “Ostrich instruction” – if someone is reasonably aware a crime is going on but is willfully blind, knowledge is imputed. US v. Jewell. RECKLESSNESS “A person acts recklessly…when he is aware of and consciously disregards a substantial risk that such result will occur or such circumstance exists.” NYPL 15.05(3). • In NY, voluntary intoxication counts as recklessness, even if the defendant doesn’t actually foresee the risk. • In NY, Reckless homicide is Man 2. Voluntary Intoxication Under NYPL § 15.05(3), if the only reason someone isn’t aware of the risk is voluntary intoxication, he is reckless. Specific vs. General Intent Some crimes – that require intent, knowledge, or recklessness – are specific intent crimes. They require some sort of actual mens rea. Negligence and strict liability are general intent – they require no specific mental state. • Easy way to keep track – if you’re Leningrad (blackout) drunk, incapable of meansends reasoning, you can’t be aware of a risk or intend a consequence, but can still be guilty of general intent crimes. • Example: Assault is intent to commit a battery. If you’re Leningrad drunk, you can’t intend the battery. • This is a high standard. Mere disinhibition does not mean no mens rea. • Key distinction: can you use means/ends reasoning? • And again, in NY, voluntary intoxication allows for recklessness, which is specific intent. • Specific intent means mistakes of fact can exculpate. • Attempts are all specific intent crimes. CRIMINAL NEGLIGENCE “A person acts with criminal negligence…when he fails to perceive a substantial and unjustifiable risk that such result will occur or that such circumstance exists. The [negligence must] constitute a gross deviation from the standard of care that a reasonable person would observe. NYPL § 15.05(4). • The standard is significantly higher than tort negligence. STRICT LIABILITY Strict liability exists in criminal law, but only in pockets, and they are controversial. In general, strict liability is appropriate only for “regulatory crimes” that are punished by fines. Prison or other penalties require mens rea. Morrisette and Staples. • Under NYPL §15.15(2), if a statute is unclear on mens rea, you never impute strict liability. • Only strict liability crimes remaining: statutory rape, felony murder, and rape. All controversial. Statutory Rape In New York, statutory rape is strict liability. NYPL 130.25-35. • In Regina v. Prince, formerly the leading British case, the court said the act of statutory rape was wrong in itself, so someone does it at his own risk. Even if he didn’t know she was 18 and no reasonable person would think so, he is still strictly liable. • In People v. Olsen, California establishes strict liability for girls under 14, negligence for girls 14-17. • In B (a minor) v. Director of Public Prosecutions, Britain overrules Prince and establishes an intent standard. • In America, there has been the same movement away from strict liability, but no desire to make it a specific intent crime. Negligence is usually what courts go for. But there are plenty of states, including NY, that use a strict liability standard. Vicarious Liability In certain circumstances, a superior can be criminally liable for the a subordinate’s acts, but not if prison is an option. State v. Guminga. ∫• But is acceptable for regulatory offenses. Example of vicarious liability for cruise control speeding in State v. Baker. Corporate Vicarious Liability In cases where only a fine is involved, there can be a rebuttable presumption of strict liability for the CEO for subordinates’ actions, but if prison is involved, there must be a mens rea requirement. • In Gordon v. US, SCOTUS strikes down a law that imputes knowledge from an employee to a CEO. • They walk back a little in US v. Park. There Park received a letter informing him of the violations, but did nothing. The court allows strict liability, but says you can’t hold someone liable for something they would be powerless to change. • There is no liability if the defendant can show he did everything possible to alleviate the situation (hyper-reasonableness). • So it’s sort of strict liability as a rebuttable presumption. Negligence-esque. There’s strict liability, but if you meet the standard, you’re fine. • Or is it a status crime? • Park only involves a fine. In US v. MacDonald & Watson Waste Oil Co., the court refuses to allow strict liability when jail is involved. • Counterargument – only jail time actually deters corporate criminals. They aren’t fazed by fines, and corporations are often structured in a way that shields executives from liability, so we need strict liability if we’re ever going to get them. Individualization We never individualize for IQ, Neuroses, Excitability, Alcoholism and Prejudice Ignorance of Law In general, ignorance of the law is not an excuse. NYPL § 15.20. • But a mistake of fact can exculpate if it negatives the mental state required for the (specific intent) crime. For example, larceny involves intending to take someone else’s property. If you mistakenly think the property is yours, then you don’t have the required mens rea. • In US v. Cheek, SCOTUS decides as a matter of policy that a mistake of fact can exculpate when someone files taxes wrong. • In Ansaldi, they decline to extend that to the drug trade. • NYPL §15.20(2)(d) says that reasonable mistake can exculpate if it involves relying on a legal interpretation made by a public official that administers or enforces the law. • Same when relying on a judicial decision. NYPL §15.20(2)(c). • While it’s assumed that people know the law, there has to be some sort of fair notice requirement. Example of registration requirement in Lambert. • In general, relying on a lawyer’s advice is not a defense. • DAR looks to Lambert and Albertini to show that if ignorance of law is prosecuted in a way that is unfair, the Due Process clause will protect citizens. Proportionality Three factors are relevant to determining if a sentence is out of proportion with the crime and violates the 8th Amendment: 1) the gravity of the harm and the harshness of the penalty, 2) the sentences imposed on other criminals in the same jurisdiction, and 3) the sentences imposed for the same crime in other jurisdictions. Ewing v. Cali. • In Ewing, O’Connor says for the majority that only if the first principle is out of line do you look at the other two. And that the first principle is pretty flexible. • Dissenting, Breyer says that to look at the first principle, you look at 1) the length of the prison term, 2) the crime that triggered the term, and 3) the offender’s prior behavior. And he thinks the Cali three-strikes law fails. • Bentham has a forward-looking view where proportionality ensures that there are incentives for low level criminals not to commit more serious crimes. JF Stephen says that proportionality ensures that legal penalties are in line with underlying moral judgments. Death Penalty • Before Furman, the death penalty was left completely up to juries. Very arbitrary. • Furman banned it, but in Gregg the Court allows it if there’s a bifurcated procedure where the 2nd step looks at the full life of the killer, all aggravating and mitigating factors. DAR says this is to mitigate the effect of race. • Atkins- can’t execute the retarded. Roper – can’t execute juveniles. They are less culpable and less deterrable. • Coker- can’t execute for rape. Emmundcan’t execute for accessorial liability (defendant doesn’t have the mens rea). • In McClesky, the court ignores significant statistical evidence about racial bias in death penalty sentencing. They say there isn’t enough evidence, and the argument could apply to all other sentencing too, so they won’t touch it. Rape A Massive Social Shift DAR says we are in the middle of a massive social shift with respect to rape law. Patriarchal Consent based No interspousal rape Rape is genderdefined (and gays don’t exist). A major emphasis on violence (rather than absence of consent) Suicidal resistance required. Interspousal rape forbidden Not gender defined Not available to sexually active/free women Available to everyone Emphasis on consent/lack of consent. No resistance requirement Common Law Elements of Rape • Force • Lack of Consent • Penetration Force • State v. Rusk shows the old idea of force. Judge overturns verdict against defendant because the woman didn’t resist “to the utmost,” even though defendant choked her. Similarly, in People v. Warren, the defendant picked the victim up and carried her away, again failure to resist used to overturn conviction. • The law has come to understand there can be nonphysical force. MPC standard is real or implied force – “threat that would prevent resistance by a woman of ordinary resolution.” • NY requires physical force or a threat. 130.00 Cali includes psychological force. • Can’t criminalize pressure – like economic pressure in State v. Lovely (drifter case). • But in State in the interest of MTS, penetration itself is enough for force. NJ only. Deception In New York, there must be force for rape. In California, the distinction is between fraud in the fact (rape) and fraud in the inducement (seduction). • Example of Boro v. Superior Court, where the victim thought that having sex with an anonymous donor was the only way to cure a disease. She still consented to have sex (the fact), even though she was induced to do so by fraud. No liability. Mens Rea New York has a negligence standard for Rape Three, NYPL §130.05(2)(d), and is strict liability for Rape One and Two (but there is a force requirement). 130.30, 35. • If there was an intent standard it would be nearly impossible to ever convict. • Four possible conseptions of nonconsent. 1) Affirmative no plus other behavior that makes unwillingness clear, 2) verbal resistance alone, 3) verbal resistance or passivity/silence, or 4) affirmative yes. Corroboration Many states used to require corroboration for rape. Fear of false accusations. Shield Laws Prevent defendants from bringing up victims’ sexual histories. • But sexual history can be relevant. Example of State v. DeLawder where the victim thought that she was pregnant by someone else and needed to make a story to explain it.) Or Neeley v. Commonwealth, where defendant was convicted because of a black hair in victim’s vagina, but wasn’t allowed to show that the victim’s boyfriend was black. • Kennedy Smith trial – prior sexual history of alleged rapists is excluded because prejudicial. Shouldn’t the same be true of victims. • Big issue of whether rape victims should be allowed to be examined by psychiatrists. Homicide (Life on the Street!) Premeditation • Largely abandoned. Traditionally the distinction between Murder One and Two. NY does not have this. • Commonwealth v. Carroll is an example of how premeditation was found in a snap decision to kill. Use of a gun, deadly weapon doctrine, rebuttable presumption of intent. • And Anderson, the tremendously brutal murder of a 10 year old girl, is the opposite. Morally terrible, worse than Carroll, but no premeditation. • And cases like mercy killings where there is premeditation, but we would want mitigation. Voluntary Manslaughter Mitigation A defendant can get a murder charge mitigated to manslaughter if he acted under the influence of extreme emotional disturbance for which there is a reasonable explanation or excuse. NYPL §125.25(1)(a). DAR: Murder can be mitigated down to voluntary manslaughter if: 1) there is reasonable explanation or excuse, 2) there is causation between the excuse and the act, 3) there is not a reasonable cooling down period, and 4) the defendant has not cooled down. • Traditional rationales for manslaughter mitigation: extreme assault/battery, mutual combat, defendant’s illegal arrest, injury or serious abuse to a close relative, or sudden discovery of spouse’s infidelity. • Plays a big role when the person doesn’t die – VMM can be the difference between assault with intent to kill and garden variety assault. • VMM is based on a reasonable person standard. But there are limits. In Casassa, a NY court rules that the reasonable person standard does not take neurosis into account. • In NY, the standard is a reasonable person in the defendant’s circumstances as he believed them to be. • Because of difficulties with an individualized standard, Britain has gotten rid of VMM and replaced it with diminished responsibility. • Key: VMM mitigates, doesn’t exculpate. Imperfect Self-Defense • In some jurisdictions, if you think you’re acting in self-defense (unreasonably), you get mitigated down the gradations of murder. Criminally Negligent Homicide Criminally Negligent Homicide is a separate crime. NYPL 125.10. Key factors: gravity of the risk, likelihood of the risk, and the actor’s purpose in taking on the risk. • The standard of culpability is much higher for criminal negligence than civil negligence. • And the standard has to be individualized. Example of the skier in Hall or the Indian parents in Williams. • The purpose of taking on the risk is taken into account. Example of Hall, where the guy was skiing like a crazy person just for fun. • There is no contributory negligence on the criminal side. Intent to do Serious Bodily Harm Murder Manslaughter. See NYPL § 125.20(1). Depraved Heart A defendant is guilty of depraved heart murder if “under circumstances evincing a depraved indifference to human life, he recklessly engages in conduct which creates a grave risk of death…and thereby causes the death or another person.” NYPL § 125.25(2) • Think of it as aggravated recklessness. Applies in cases with low moral purpose – e.g., drunk driving, drag racing, Russian Roulette. • Gravity and probability of harm must be high and purpose must be low. Felony Murder If a defendant is committing a felony, and in the course of/in furtherance of/in flight from that felony someone dies as a result, he is liable for their murder. Terms and condtions apply. New York • Felony Murder only applies to certain enumerated felonies. • It doesn’t matter who does the killing (cops, victims, or felons). • The predicate felony can be far removed from the actual death, as long as it is in the same causal chain. • But no felony murder if the person who dies is a cofelon. • NY has an affirmative defense if you 1) did not commit, cause, or aid the homicidal act, 2) were not armed with a deadly weapon, 3) had no reasonable ground to believe any other participant had a deadly weapon, and 4) had no reasonable ground to believe that any other participant would engage in conduct likely to cause death or serious harm. California • Felony Murder only applies to felonies that are “inherently dangerous” in the abstract. So Arson, but not embezzlement. • Merger doctrine – you can’t have Felony Murder if the predicate felony merges into the killing itself – example of assault, or burglary with intent to assault/kill. • Only applies to people killed by cofelons. People killed by cops/victims don’t count. • Armed robbery doesn’t merge. Burglary sometimes does. United Kingdom The UK has no felony murder rule. You have to go for depraved heart. • MPC suggests that if someone dies in the course of a felony, there is a rebuttable presumption of depraved heart. No jurisdiction adopts this. • But think about the pickpocket/handgrenade example – here punishment and culpability don’t match. Violates retributivism. Misdemeanor Manslaughter • California has a misdemeanor manslaughter statute. If someone dies as a result of your misdemeanor, it’s manslaughter. Causation In general we say causation ends when someone else commits a crime intentionally, or is grossly reckless. Unless the original person created a situation in which the action was not an unreasonable response. • DAJR says that causation in criminal law is closer to moral responsibility than any scientific definition of cause. In a tough fact pattern, ask who is morally responsible. • Negligence does not break the causal chain. • Nor does medical malpractice if the guy would have died without help. • And whenever you have depraved heart, liability sticks with the defendant. • California uses an “extraordinary result” test, as shown in Acosta. There, two helicopters colliding was not a highly extraordinary result (although depraved heart was negated because they weren’t foreseeable.) • In NY, the test is whether the action was a “sufficiently direct cause” of the death, and the ultimate harm is foreseeable. Arzon. • Root and McFadden – no liability in drag racing for the death of the other drag racer, but liability is found for the death of a six year old girl. Again, closer to moral responsibility than actual proximate causation. • And if there’s depraved heart, courts will imply causation. Suicide and Causation Typically, if it’s a free and rational act, suicide will break a causal chain. Campbell. • In New York, assisting a suicide is second degree manslaughter. NYPL § 125.15(3). • But consider Stevenson (Indiana), where a multiple rape victim who killed herself didn’t shield the rapist from liability, because she was still under his control. Accessorial Liability Accessorial Liability In order to be liable as an accessory, a defendant must have causal significance to the criminal act, and the SAME MENS REA as the person who actually carries out the act. • It is no defense for the accessory if the principal did not have the necessary mens rea. NYPL §20.05. • Each person can be liable for a different degree of the same offense. NYPL § 20.15. • Mere presence is not enough. Have to have same mens rea and causal significance. Hicks. • Have to have an actual nexus between the principal and the accessory. They need to know and work with each other. Gladstone. • California has the Luparello rule – intent is imputed for all crimes that are reasonably foreseeable. Guns and swords case. • There can be accessorial liability for unintentional crimes if the same mens rea was shared. Example of defective ship boiler in McVay. • You can have people working at odds who create a dangerous situation and are thus accessories to each other. Example of drag racers or the Red Hook gang shootout in Russell. • England is crazy liberal with accessorial liability. Example of the music journalist clapping and writing a positive review in Wilcox. • Causal significance can be very weak. Example of the judge stopping a telegram in Tally. It wasn’t clear the telegram would have stopped the murder. • A victim can’t be an accessory. So a minor isn’t an accessory to statutory rape. Tyrell. • Can’t have accessorial liability for a crime that doesn’t happen. The accessorial liability is limited by the actual harm done. Richards. • A principal can be eligible for defenses and mitigation, but those defenses are not imputed to accessories. Othello gets mitigation. Iago doesn’t. Criminal Facilitation A defendant is guilty of criminal facilitation if he believes it probable that he his helping someone to commit a crime, he acts in a way that aids someone in committing a crime. NYPL §115.00 • Way to get someone who helps a criminal, but isn’t an accessory. Inchoate Crimes Attempt Attempt requires only intent and proximity. • Attempt merges. If it culminates, then you become either an accessory or a principal. • Stephen thinks you’re less blameworthy if the crime doesn’t happen. Hart and Schulhofer think that you are exactly as culpable. This seems to be gaining steam – penalties for attempt are getting closer to those for the actual crime. • Can’t have attempted negligence. Attempt involves intent. • Can’t have attempted felony murder. But attempt can be a predicate felony. • Proximity is the key question in attempt. If there is a locus penitentiae – an opportunity to repent, then no attempt. • In the UK, attempt is only possible when you take the “last step” of the crime. Everything before that is preparation. Eagleton. • NY has the Rizzo rule, where the defendant must be “so near to its accomplishment that in all reasonable probability the crime itself would have been committed but for timely interference.” • Federal courts have a “substantial step” rule. • If you make the proximity rule too tight, you frustrate good police work. If you make it too loose, you allow for massive violations of civil liberties. Example of McQuirter, the Alabama “attempted rape” case. • Especially complicated in stalking statutes. In NY, the stalkee has to tell the stalker to stop. Reckless Endangerment Reckless Endangerment is when a defendant recklessly engages in conduct that creates a substantial risk of harm to others. NYPL § 120.20. • Also applies to many abortive crimes. Solicitation Solicitation requires only intent and solicitation. • Solicitation merges. If the crime happens, you’re an accessory. • In US v. Church, a federal court holds that soliciting a hitman amounts to attempted murder. It’s a “substantial step.” • Runs into free speech problems. In general, public speech (think Black Panthers) is protected. Clandestine criminality isn’t. Conspiracy Conspiracy has three requirements: intent, an agreement, and an overt act (NYPL § 105.20) to further the conspiracy. NYPL § 105.xx. • Conspiracy DOES NOT MERGE. Even if the act intended occurs, the conspirators are still liable for the conspiracy itself. • Recognizes that people are much more dangerous in groups, so special penalties. • An exception to the hearsay rule. And venue advantages. And large conspiracies tried together. • Renunciation – to get out of a conspiracy, you have to contact the police and actually prevent it from succeeding. NYPL § 40.10(4) • Pinkerton rule – once you have a conspiracy, intent is imputed for anything reasonably in the scope of the conspiracy. CA has this. But Alvarez says it doesn’t apply to minor actors. • In NY, you have to get the defendants via accessorial liability. • Mere gang membership is not enough for a conspiracy. Garcia. • A conspiracy can be inferred based on a mutual understanding, even without an explicit agreement. Interstate Circuit. • Wharton rule: Can’t have a conspiracy when the crime is inherently conspiratorial. • When knowledge becomes intent: when the defendant has a stake in the venture, when there is no legitimate use for services, when the volume of business is disproportionate to any legitimate demand. Lauria (CA) (prostitute phone line case). • Kotteakos rule – no liability in spoke conspiracies. Has to be a “rim.” Concurrent criminality is not enough. • NY allows one person conspiracies. NYPL § 105.30. CA does not. • Key takeaways – Overt act requirement, target crime must be illegal, ignorance of law is no excuse, can have a one party conspiracy, can convict one party with reasonable doubt as to the other, and renunciation requirements are demanding. RICO RICO allows the imputation of a “rim” to a spoke conspiracy, but there must be two or more predicate crimes on each spoke (three in NY) and some sort of criminal “enterprise.” • Critical to going after large criminal organizations. Allows use of hearsay evidence against low level operatives, which you can then run up against the kingpin. • Relies a lot on prosecutorial discretion. DEFENSES Justifications vs. Excuses Key distinction – with justification, the act done wasn’t wrong. With excuses the act was wrong, but somehow forgiveable Necessity Justification • Balance of evils • Legitimacy of means Necessity Excuse – coercion by circumstances Self Defence Mistake Defense of third party Accident Defense of property Arrest Duress Necessity Insanity Intoxication Self-Defense Common Law Requirements for self defense were 1) reasonable belief, 2) imminence, 3) necessity, and 4) proportional force. • Can only use deadly force if deadly force is being used against you. Even an unjust aggressor has a right to life. • Question of how much you individualize the standard. If you do it too much, you get Bernie Goetz. Key is reasonable belief that you are being threatened. • In other jurisdictions, there is a doctrine of imperfect self-defense that mitigates. • “No hit rule” – cannot use physical force to resist arrest, even if unlawful. NYPL § 35.27. • In general, can stand your ground if using nondeadly force, but have to retreat before using deadly force. Abbott. • Initial aggressor rule. No right to self defense if you are the initial aggressor. NYPL § 35.15(1)(b). This applies if the crime comes to a stop and you reignite it. Peterson. • There’s no balance of evils requirement with self defense – your act is privileged. Battered Woman Syndrome BWS Evidence is relevant on credibility. A battered spouse is more likely to know when her batterer actually intends to kill her. Relevant to necessity, imminence, proportionality. And it helps to explain why she doesn’t leave. • The knowledge/self defense prong is more like a justification. The pathology/why she can’t leave prong is more like an excuse. • DAR says this allows juries to reasonably evaluate the defendant, rather than ruling from stereotypes. • People v. Humphrey – Cali allows BWS evidence in, but doesn’t want a “reasonable battered woman” test. Question of how much to individualize – does it negate women as moral actors? • Also some concerns with the validity of the data on BWS. • Imminence is key in cases like Norman where a woman was brutally abused (whored out in a truck stop, made to drink from a dog bowl) and shot her husband. No self-defense there. • Contract killing may be different. No imminence. • Cohen article. This is similar to tyrannicide, which is okay. Defense of Others In New York, you can use physical force if you reasonably believe it necessary to protect a third person. Same rule as selfdefense. NYPL § 35.15(1) Defense of Property Defense of property is a murky subject, but the key seems to be whether you reasonably believe force is necessary. Compare the spring gun in Ceballos (CA), the Japanese immigrant in the Halloween cosrume in Hattori, and a robbery victim shooting his fleeing robber in Sydnor. Arrest In New York, a policeman can use all necessary physical force to effect an arrest, but can only use deadly force if the escapee has a deadly weapon, or if the offense was a felony with a deadly weapon, kidnapping, arson, escape, or burglary. NYPL §35.30(1). But he can’t do it recklessly. NYPL §35.30(3). A citizen can use deadly force only if he reasonably (and CORRECTLY) believes the escapee to have committed murder, manslaughter 1, robbery, rape, or criminal sex act. §35.30(4). Reasonableness is NOT enough. • In Tennessee v. Garner, SCOTUS rules that deadly force is only acceptable if the suspect “poses a threat of serious physical harm, either to the officer or others. Found in fourth amendment (unreasonable seizure). And it’s a death penalty without due process. Necessity A necessity defense is available if there is 1) legitimacy of means and 2) a favorable balance of evils (less harm done by committing the crime than not committing the crime). NYPL § 35.05 (2). • Test for prison escape: People v. Loverkamp (CA) requires 1) a specific threat of death/substantial injury/forceable sex, 2) no time to complain, 3) no ability to resort to the courts, 4) no force or violence toward prison personnel, and 5) prisoner reports to authorities once he’s safe. • Federal courts don’t allow necessity for indirect civil disobedience. Schoon. NY doesn’t allow any civil disobedience case to go to the jury on necessity. NYPL § 35.05(2) • America doesn’t allow coercion by the circumstances (which is more duress). • In Britain there is no necessity defense for murder. • Big issue of this on torture. Israel won’t allow a blanket policy allowing torture in times of necessity, but will allow defense in individual cases. Duress Duress requires 1) an imminent threat to yourself or others 2) that a reasonable person could not resist. NYPL § 40.00 • Toscano stands for the idea that the threat doesn’t have to be immediate, just something that would be irresistible to a person of ordinary firmness. • Numbers don’t matter the same way they do in necessity. It’s up to the jury. • In New York, duress can be an excuse for homicide. In Britain, it never can. • In US v. Fleming, there is no duress for an army officer who aided the Koreans under threat of a death march. • In US v. Contento-Pachon and Regina v. Ruzic, duress is given to drug mules who smuggle under threats to families at home. • In Erdemovic, Duress is not allowed for a Serbian officer ordered to kill civilians or be killed himself. This is homicide, and the balance of evils was way against him. Intoxication Traditionally, intoxication negates intent, but you have to be Leningrad drunk, not just disinhibited. NYPL §15.25. • In both NY and Cali, assault with a deadly weapon gets defined as general intent. Cali in Hood, NY in NYPL §120.00 (assault three). • And don’t forget, voluntary intoxication equals recklessness. NYPL § 15.05(3). • And drunken failed assault can still be reckless endangerment. • Involuntary intoxication seems like a complete defense, but it definitely doesn’t apply if you’re merely disinhibited. Regina v. Kingston (pedophile case). Entrapment There is an affirmative defense if the defendant was “induced or encouraged” to commit the crime by a public servant seeking to obtain evidence against him. NYPL § 40.05. • Basically, the defendant lacked the mens rea. The officer gave it to him. Insanity Under M’Naughten’s rule, a defendant is exculpated if at the time of the crime he 1) has a mental disease or defect that 2) means he doesn’t understand the nature or legality/morality of his act and 3) causes the act. • In M’Naughten’s case, he genuinely thought the Prime Minister was trying to kill him. Thought it was self-defense. Didn’t understand the legality/morality. • Note that political and religious views, no matter how whacky, do not qualify you as insane. Otherwise you could be committed for having views the government sees as crazy. • On the other hand, a deific decree does give rise to insanity. Can’t resist God’s orders. • People exculpated for insanity don’t go free. They are civilly committed. Some states have a post trial hearing, others have automatic commitment – standard is whether the person is a danger to themselves or others. • America experimented with the irresistible impulse rule and the Durham rule, where any time a psychiatrist declared a defendant insane, they were exculpated. The US ends up with the modified ALI rule, where a defendant is exculpated if he 1) has a mental disease/defect that 2) means he doesn’t understand OR APPRECIATE the nature or legality/morality of his act and 3) causes the act. • The “or appreciate” language relaxes the standard a bit. Covers people who are completely dissociated. Problems of empathy. • Previously there was an exception for people who lacked a substantial capacity to conform to the law. Like Kleptomaniacs. But this got thrown out after Hinckley. • There’s a lot of debate about whether psychopathy (when someone knows what they’re doing but is incapable of empathy) should exculpate. • DAR says there is probably a Constitutional right to an insanity defense. Attempts to abolish insanity • The Modified ALI standard could be lessened. Arizona got rid of the nature of the act prong but kept the legality/morality prong. Upheld in Clark v. Arizona. • But knowledge about the nature might still be admissible to negate mens rea. Clark thought he was killing an alien – didn’t have the intent to kill a human being. This is key – prosecution has to prove mens rea beyond a reasonable doubt. Defense just has to prove insanity by clear and convincing evidence. • And some states have a “guilty but mentally ill” verdict where defendants get put in special prisons and on drugs. Automatism In the United States, automatism is a complete defense – no actus reus. The UK does epilepsy, somnambulism, etc. as a mental disease/defect. Diminished Responsibility Germany and the UK allow for diminished responsibility – diseases short of insanity that can mean a defendant is less culpable. It mitigates at sentencing. Covers cases like Cassassa. • NY doesn’t have this, but does have VMM. Addiction as a Mental Disease • SCOTUS declines to allow alcoholism to exculpate in Powell. Being drunk may not be a choice, but being drunk in public is. • Marshall is concerned about indefinite commitment for alcoholics/addicts. • Court rejects the idea of drug addiction as a mental disease in US v. Moore. • DAR – we know incentives can get people off drugs. There is some level of volitional control that the criminal law can operate on. • Although there is the harm issue with drugs. • Judge Wright thinks addiction should be a defense against possession. • Judge Bazelon thinks addiction should be a defense against all crimes. Armed robbery! • And rotten social background question. Reasonable Police Work A policeman has a defense for any conduct that is part of reasonable police work. NYPL § 35.05(1). Impossibility Under NYPL § 110.10, a crime’s impossibility is no defense. As long as the crime would have been possible under the circumstances as the defendant thought they were, he is liable, but only for attempt. • Overrules Jaffe, which made a complicated (and senseless) factual/legal impossibility distinction. But that’s still valid in the federal system. • Think of Dlugash (shooting at a dead body, thinking it was alive), or the voodoo hypo. • Note that true legal impossibility is a defense. If what you thought was a crime isn’t actually criminal, then you aren’t liable.