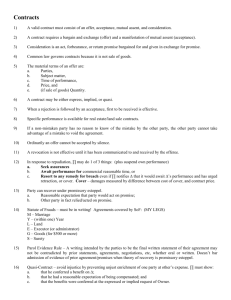

2 29 rule)

advertisement