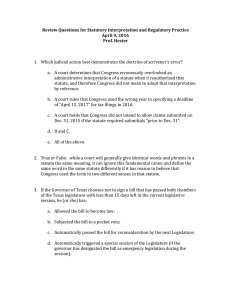

T F L P

advertisement