Employment-Based Torts? Who Cares?

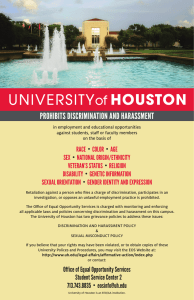

advertisement

STETSON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW PRE-CONFERENCE WORKSHOP WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2000 Preventing Tort Liability and Losses – Identifying the origins of tort/accident liability and defining approaches that limit personal injury claims for civil damages Employment-Based Torts? Who Cares? Discrimination Defamation Negligent hire/retention Wrongful termination Constructive Discharge I. Stop Thinking Like a Lawyer (or at Least Start Thinking Like a Plaintiff’s Lawyer) Anyone who practices in higher education will appreciate the very unique environment in which we work. We can agree that the practice is usually enjoyable and always challenging but, given certain characteristics of higher education, often not directly transferable to a similar substantive practice in other industries. Among the great joys of practicing in this environment is the opportunity to practice preventative law. Most institutions of higher education fancy themselves as progressive environments dedicated to maximum individual freedom, often at “corporate” expense. So, while all employers may operate in the same general environment, universities as a whole set higher expectations for employer-employee relations. We provide more due process, more opportunities for internal review and bring more people into the decision-making chain. Identification and prevention of risks related to employment can be approached in two fundamental ways. One way is to understand the expectations imposed by statute, common law or institutional regulation. We learn the rules and if time permits disseminate those rules through newsletters, briefings and workshops. But is it effective to brief supervisors on the elements of the prima facie case for a Title IX violation? What is our goal when we talk about the law to supervisors? Do we really want our clients to be thinking about when behavior stops being merely offensive and violates state or federal discrimination law? Can we be content as an employer if the behavior falls just below the legal threshold? Can we effectively train supervisors using legal thresholds as baselines? Is there a better, more practical way to think about behavior in the employment context? One alternative method is to de-emphasize the rules in order to focus on the underlying fairness of the behavior in question. In my experience university administrators want equal treatment for all employees and a healthy environment free from behavior that impedes efficient job performance. They want fair evaluation processes, the ability to reward good employees and rehabilitate or fire bad ones. The laws proscribe certain behaviors but, being negative by definition, fail to provide the day-to-day guidance our clients can use. But to paraphrase Justice Stewart, we all know fair treatment when we see it. So, managing risk might be more effective if we train managers to “know it when they see it” rather than expecting them to apply a given set of facts to the law. Following this assumption, I propose we adopt the perspective of plaintiff’s counsel and think facts first with causes of action to follow. Consider the following scenarios drawn from recent matters involving Northeastern University: A. Professor Freehand is the senior member of the department. Most of his teaching involves graduate courses. Two years ago he took a female graduate student out to dinner. During the meal he told her she wasn’t his type but that he was attracted to the “litheness” of her spirit. Leaving the restaurant he called her a sweetheart, tried to put his arm around her and kiss her on the cheek. The student complained, he apologized profusely and offered to resign if it ever happened again. It did. This time he took a grad student out to dinner, told her that she was not his usual type but that he was somehow attracted to her spirit. He asked if she wanted children. Getting up to leave, he called her a sweetheart and kissed her on the cheek. They left together and he offered to drive her home. She accepted. That evening she called a faculty member of the department who suggested she contact the affirmative action office. They took her complaint and mediated a resolution that included Freehand’s sabbatical for 2 quarters and agreement to stay away from her. He complied with the terms of the agreement but on one occasion she saw him in his office. Other than that they had no contact after the dinner. The student was enrolled through the quarter but did not complete her classes. She dropped out shortly thereafter. A few additional facts. The student had withdrawn from several courses prior to making this complaint and had complained in writing that the program did not suit her needs. She filed her complaint nearly 2 years after she left the university. In discovery you have learned that she had an affair with an older professor while in her undergraduate program. B. Mr. Dean was recently promoted to manage several graduate programs in a professional school. He’s well known throughout campus and the business community. He’s drinking buddies with many faculty and administrators. He has been very successful running certain programs. There are no prior complaints about his behavior. He was hired to rejuvenate some underperforming programs. Shortly after his arrival, several women began to complain about his management style, his general behavior and his evaluation of their performances. He claims they are all poor performers who need clear, firm guidance. A few months go by and the complaints continue. Allegation of sexist language and hostile and abusive shouting matches after long boozy lunches emerge. Two of the women file grievances through the affirmative action process. Investigation of the complaint reveals substantial, credible evidence that at least some of the allegations are true. C. Jack has worked in the Political Science Department for 20 years. As the administrative assistant he is responsible for the clerical functions of the Department. However, over time he shifted those duties to others, and assigned himself tasks as “liaison” between faculty and students, “advisor” to students and “executive officer” to the department. He comes in when he wants and leaves when he wants. He keeps his own hours and grants himself compensatory time off if he determines he’s worked overtime. On that theory he now takes Fridays off. Last year the department chair retired. He was replaced by an outsider who was quickly dismayed by Jack’s situation. The new chair met with Jack, explained her expectations and followed-up in writing. Jack has resisted every change. He and the chair have exchanged several lengthy detailed memoranda. The Chair rated Jack “conditional” for his first performance appraisal. Jack responded with a 7 page memorandum with a detailed rebuttal of the appraisal and a critique of the chair’s management style. The chair wants to fire Jack. She gives him one last chance to perform by a given date. Just before that date, Jack takes an emergency medical leave. He never returns to work. Jack’s personnel file includes nearly 10 years of superior performance evaluations. It turns out that the prior Chair simply signed the evaluations that Jack completed for himself. Each of these fact patterns implicates several causes of action and related defenses. But if our goal is to limit liability by identifying and avoiding potentially tortious behavior, is that the best place to begin our analysis? Are our clients better served by allowing them to think about fundamentally appropriate behavior rather than the legality of their behavior? Some or all of the behaviors listed above may not violate existing laws but are they still unwelcome in the employment environment? II. Overview of Laws in the Employment Context Any review of the laws that govern the employment relationship should begin with federal discrimination laws. In addition, several common law causes of action recur in the employment context. TITLE VI: The first applicable statue involving potential employer liability for discrimination in the workplace is Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The statute is defined by Title 42 U.S.C.A. §2000d which states, “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Title VI was created to prohibit racial discrimination in any area where federal funds are being used. This title is applicable to any area where federal funds are being used, not just in educational programs. Title VI’s authority is based on Congress’ ability to implement policy through its spending power. By receiving federal funds, an employer is entering into a contract with the federal government that mandates compliance with the racial discrimination provisions of Title VI. The main complaint about Title VI is that it has been unclear what remedies a discriminated party has under the title and subsequently, the case law tends in this area tends to be vague. The seminal case in this area is Guardian Assoc. v. Civil Service Commission of the City of New York, 463 U.S. 582 (1983). In Guardian, a case involving black and Hispanic members of the City of New York Police Department who sued the department because of a discriminatory layoff policy, the Supreme Court established that there is a private cause of action under Title VI (first established in Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677 (1979)) and stated that there has to be intentional discrimination for a plaintiff to get relief. In addition to a private civil suit, a plaintiff may seek administrative relief by filing an Office of Civil Rights (OCR) complaint with the appropriate federal agency. Under an administrative enforcement action, if an employer is found to have violated Title VI, federal funding will be withdrawn. The Department of Education is charged with investigating Title VI violations under OCR procedure. The Supreme Court in Guardian added to the confusion by ruling that an agency enforcing a Title IX action may attempt to enforce a racial discrimination claim that involves unintentional/ negligent discrimination. Under the OCR process, an educational institution is vicariously liable for any racial harassment done by its employees. Schools are also vicariously liable for racial harassment of students by other students if the institution knew or should of known about the harassment. This student-on-student harassment standard is one of negligence. An employer’s liability for this type of harassment is identical to the Title VII standard. TITLE VII: Title VII is codified into law in Title 42 U.S.C.A. §2000 which states that is unlawful to discriminate because of an “individual’s race, color, religion, sex or national origin” in the employment context. Title VII is the quintessential portion of the civil rights law (created in 1964 and amended by Congress in 1991) involving employment. This title applies to all employment, both public and private, irrespective of federal funding (Langraf v. USI Film Products, 511 U.S. 244 (1994)). Unlike the other titles discussed in this memo, Title VII derives its power from Congress’ authority to regulate interstate commerce, not the Spending Clause. Title VII’s primary goal is “eradicating discrimination throughout the economy and making persons whole for injuries suffered through past discrimination” (Landgraf at 251). By relying on the Spending Clause, other titles do not have as much impact as Title VII because any entity may avoid liability by simply refusing federal funding. In addition to being applicable in more employment situations, under Title VII, employers have a higher standard of liability when compared to other titles. Employers are vicariously liable for all discriminatory actions taken by their employees, regardless of fault. Traditional principles of agency law apply. A principal is liable for any discriminatory act performed by any agent during the scope of his or her employment (Restatement of Agency §219). For any discriminatory act done outside the scope of an agency relationship, an employer is liable under a negligence standard, i.e. the employer is liable if it knew or should of know about the discrimination (Smith v. Metropolitan Sch. Dist Perry Tp., 128 F.3d 1014 (7th Cir. 1997). It is important to point out that under both Title VII liability standards, the intent to discriminate is irrelevant. An employer is either vicariously liable under agency or negligently liable otherwise. Like other articles, a plaintiff may seek a private, civil cause of action or use the administrative approach. Like Title VI, any OCR action can involve both agency and negligence liability. The only defense to a Title VII action is if an employer mitigates the effects of a discrimination act and has preventive programs in place. TITLE IX: Title IX is codified into law in Title 20 U.S.C.A. §1681 which states: No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Simply put, Title IX outlaws sex discrimination in any educational program that receives federal funds. Title IX parallels Title VI in almost every aspect except it applies to sex discrimination, whereas Title VI applies to racial discrimination. Title IX relies on the Spending Clause to enforce its provisions and the analysis in this area is identical to the Title VI analysis. A plaintiff has the same two remedy options under Title IX as the titles above. It is important to differentiate between the two forms of sexual harassment. The first form is the “quid pro quo” variety. Like Title VII, courts will find Title IX employers vicariously liable for this form of sexual harassment. The employer does not need prior notice (Saville v. Houston County Healthcare Authority, 852 F. Supp. 1512 (M.D. 1994)). The second and more common form of harassment is the “hostile work environment” variety. The following discussion pertains to sexual harassment in the “hostile environment,” teacher-to-student context. Like the previous articles discussed above, there have always been questions about what the standard for employer liability is and what the remedy provisions are under Title IX. In Franklin v. Gwinnett County Schools, 503 U.S. 60 (1992), a case in which a teacher sexually harassed a student in an elementary school, the Supreme Court held for the first time that a school district could be liable for monetary damages for sexual harassment by its teachers. Franklin was the first case that changed the parties involved in a Title IX suit –any suit now was between the educational institution and the victim. The perpetrator was now left out of the Title IX process. However, Franklin was distinguished by the seminal case, Gebser v. Lago Vista Independent School District, 118 S.Ct. 1989 (1998). Gebser involved sexual harassment of a high school freshman by her teacher in Texas. The plaintiff was coerced and acquiesced into having sexual intercourse with the teacher on numerous occasions. Parents of the student filed suit after the police caught the student and the teacher having sex in a wooded area. The Supreme Court redefined the standard of employer liability for this form of sexual harassment by holding that the school district was not liable under Title IX because a school official did not have “actual knowledge of or show deliberate indifference to” the harassment. The court eliminated the agency and negligence standards of liability. Any defendant must have an intent to sexually discriminate. By reaching this decision, the Supreme Court called into doubt the OCR and Title VII standards of liability (agency plus negligence) and the sexual harassment guidelines published by the OCR (the court questioned the timing of the publication of the guidelines which was right before the case went to the Supreme Court). The Gebser decision raised serious doubts about what the definition of an “appropriate official” for liability purposes is. The only guidance the court provided in subsequent decisions was that the official must be in a position to do something about the discrimination, such as a member of the school board. Thus, the standard of employer liability for a private, civil claim brought under Title IX is that a school official must have “actual knowledge of or deliberate indifference to” a sexual harassment incident for an educational institution to be held liable and though unclear, any OCR compliant uses the same liability standard. Although not a focus of this memo, the student-to-student sexual discrimination standard under Title IX is defined by Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, 119 S.Ct. 1661 (1999). The liability standard is extremely similar to the standard defined in Gebser. In Davis, the Supreme Court ruled that any educational institution must know about the harassment and the misconduct must be “severe, pervasive, and objectionably offensive.” Teasing between classmates is not enough to meet the threshold. III. Common Law Torts in the Employment Context The Employer’s Duty to Maintain an Appropriate Environment Constructive Discharge: The involuntary resignation of an employee. The employer deliberately makes conditions so intolerable that the employee is forced to resign. Defamation: Communications between a supervisor and an employee that relate to the employees work enjoy a qualified privilege. They are not defamatory unless they are “published” and the information is either known to be false or disseminated with reckless disregard for its truth or falsity. The Employer’s Duty to Third Parties for the Acts of Employees Respondeat Superior: An employer is responsible for the employee’s actions taken within the scope of employment. Negligent Hire: Employers have a duty to use reasonable care in hiring employees. The duty is directly linked to the nature of employment. For example, the extent to which the job entails a potential of risk to members of the public or third parties or involves special skills may heighten the duty to ensure that the individual is capable of performing the job in the manner anticipated. Generally, the duty does not include an obligation to investigate an applicant’s past beyond normal, reasonable limits. Negligent Retention: Employers who retain employees when they know or should have known of the employee’s incompetence or other bad behavior may be liable for the injuries caused to third parties the incompetent employee. The Employee’s Right to Employment/Due Process Wrongful Termination: Wrongful termination may sound in tort or contract. In general, the contract claim arises from some element of the employment relationship as created by the employer and the employee. The tort of wrongful termination relies on the breach of a duty imposed by law. For example, state or federal law may protect the rights to re-employment after injury, on return from military service or after jury duty. Whistleblower Protections: State and federal laws prohibit termination of an employee who has reported activity by and employer that is illegal or violates certain statutory provisions.